Ann Beattie published her first story in The New Yorker, “A Platonic Relationship”—about a woman who has left her husband in search of “a better world” only to discover that she is afraid of sleeping alone—on April 8, 1974, at the age of twenty-six. The story was praised on its acceptance by the magazine’s fiction editor, Roger Angell, for its extraordinary “sparsity.” In it, Ellen has separated from her husband after taking night classes at the university. She finds a roommate, Sam, a passive type to whom she grows more and more attached—if only platonically—until Sam abruptly informs Ellen that he is leaving to “see the country.” Ellen subsequently gets back together with her husband, but this development is described so tersely you could almost miss it; their reunion seems to make little emotional difference to her.

At the story’s close, while driving to the grocery store with her husband, she seems to imagine herself riding off on a motorcycle with Sam. The ending feels almost arbitrary and anti- climactic—and yet somehow the story’s refusal to find a tidy conclusion was a source of its peculiar power. It is up to us to infer that Ellen craves independence but doesn’t know how to live without a man.

Over the next two years alone, Beattie published eight stories in the magazine—a remarkable accomplishment for a fiction writer so young, since The New Yorker, then as now, was perhaps the most sought-after home for short fiction. Beattie’s pieces didn’t resemble most other New Yorker stories. They avoided dramatic confrontations and extended examination of their characters’ inner lives. They had almost no imagery and rarely used elegant metaphors; they were not propelled by event, but by omission and jump cuts. Little “happened” in a traditional sense. In “Fancy Flights,” a man separates from his wife and smokes a lot of hash while house-sitting. In “Snakes’ Shoes,” four characters have a conversation on a rock about snakes. But in their understated way the stories captured fleeting moments of loss. When Beattie first met John Updike, he told her, “You figured out how to write an entirely different kind of story.”

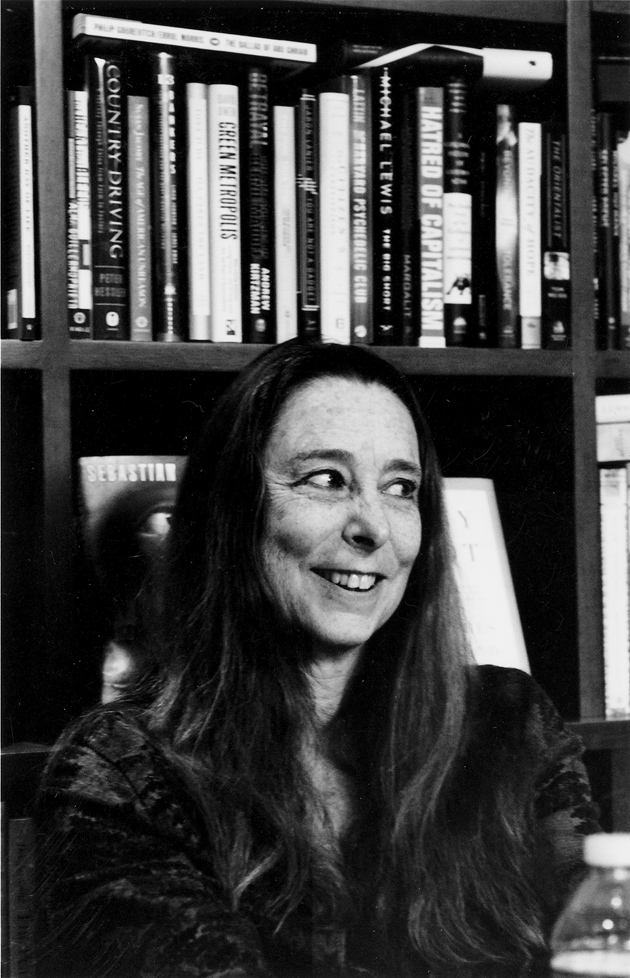

By the time Beattie published her first books, Distortions (a short story collection) and Chilly Scenes of Winter (a novel), in 1976, she had earned a reputation as a virtuosic chronicler of the zeitgeist—an unparalleled portraitist of disaffected upper-middle-class youth coming of age in the 1970s. She was heralded for her new, terse, emotionally cool style. Her deft ironies powerfully captured the skeptical mood of her peers, leading critics to talk of a “Beattie Generation.” By 1980, Beattie was one of the few working writers—Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag, and Joan Didion also come to mind—recognizable to strangers on the street.

Today, even though she has continued to write and publish steadily—since 1976, she has written sixteen books, including eight story collections, seven novels (the best-known may be Picturing Will, 1990), and one novella—Beattie’s cultural reach has vastly diminished. While she continues to be studied in MFA programs, the author who once epitomized early-career success is no longer a household name. Certainly, no one speaks of a Beattie Generation anymore. Critics have busied themselves asking why, but the question pigeonholes Beattie’s work by holding it accountable for being sociologically “representative.” Beattie herself always objected to the critical focus on her as the voice of a generation, telling Joyce Maynard in The New York Times in 1980 that reading a writer through this lens was “pretty reductive.”

The publication of The New Yorker Stories—which comprises the forty-eight stories she published in the magazine between 1974 and 2006 and contains much of her best work—invites us to look again at Beattie’s career and reminds us of the ways she expanded the scope of the American short story.1 Beattie was, by temperament, always more of a short story writer than a novelist. She has said that she writes in an improvisatory manner, drawing on the songs and objects around her as “found art” and exploring their associative qualities. (As you might imagine, this technique wears thin in a work of any length.) The New Yorker Stories shows that the conventional view of Beattie’s career has obscured her more notable achievements, overemphasizing her role as a spokesperson of a generation and underplaying the steady evolution of her complex, idiosyncratic style.

Reading the earliest pieces in The New Yorker Stories—those published in her books Distortions and Secrets and Surprises (1978)—it is not difficult to see why readers and critics saw the young Beattie as a literary ambassador of the baby boomers. They were the people she wrote about, in a way that seemed clued-in (tossed-off references to Jules and Jim, Mick Jagger, Fritz Perls, “blues,” “reds,” and the plot of Joan Didion’s Play It as It Lays are vital to the texture of her work) and strangely mature for an author so young. She was immersed in her generation, yet also had a critical distance from what she saw as its precious nostalgia for the 1960s. Many of her characters, like Sam and Charles in Chilly Scenes of Winter, already seem to feel, in their late twenties, that the best years of their lives have passed. After receiving a Christmas letter from a couple explaining that they recently broke up, Sam implores Charles, “Isn’t anybody happy? Or even sane?” When Charles’s upbeat, effective younger sister accuses the two friends of being depressed, Sam retorts, “You’d be depressed too, if you felt the way I do.” Beattie’s position toward her generation’s nostalgia was lightly satirical yet also sympathetic, and it resonated.2

Advertisement

From the start, Beattie masterfully depicted the fraying relationships that were becoming increasingly common in the post-Woodstock generation: seeking sexual liberation and drawn to the rhetoric of second-wave feminism, her characters divorce, separate, and take up with new partners, aimlessly looking for “a better world” and never finding it. “Are you happy?… Because if you’re happy I’ll leave you alone,” a man says to his older brother, who is about to get married, in “Dwarf House.” To the degree that Beattie’s stories had a plot, it often concerned people breaking up and finding new partners. In “Vermont,” a woman whose husband has left her takes up with a neighbor, Noel, whose wife has left him; she doesn’t love him but he doesn’t care. “Next, Noel will ask me to marry him. He is trying to trap me. Worse, he is not trying to trap me but only wants me to move in so we can save money.”

Beattie brought a dry wit to her descriptions of her characters’ romantic tribulations. “Plant dead, wife gone, Michael still has his dog and his grandmother”—this is how Beattie introduces the directionless main character of “Fancy Flights,” one of her finest stories. Having separated from his wife, who thinks he does too many drugs, Michael is

living in a house that belongs to some friends named Prudence and Richard. They have gone to Manila. Michael doesn’t have to pay any rent—just the heat and electricity bills. Since he never turns a light on, the bill will be small. And on nights when he smokes hash he turns the heat down to fifty-five. He does this gradually….

As the story progresses, Michael ends up finding his way back to his wife, Elsa, but Beattie makes it clear that their relationship might sour again. Michael, who is supposed to be looking after his daughter and her friend, has gone to the bathroom to get stoned when his wife comes home:

When he hears Elsa come in, he leaves the bathroom and goes into the hall and puts his arms around her…. Mick Jagger sings to him: “All the dreams we held so close seemed to all go up in smoke…”

“Elsa,” he says, “what are your dreams?”

“That your dealer will die,” she says.

It is the surface pleasures of the language and the tart charge of her dialogue that sets the story apart.

Beattie’s strongest work—the short stories “Vermont,” “Fancy Flights,” “Weekend,” “Colorado,” “A Vintage Thunderbird,” for example—subtly captures the broader social upheaval of the 1970s. Her early characters have rejected the traditional bourgeois values of having a family and owning a home, yet they have also rejected the revolutionary idealism of the 1960s counterculture, and it is not clear what is left for them. They believe in neither conventional models nor radical dreams. In “Colorado” (published in 1976), Robert and Penelope are friends who have no sense of vision for their lives; Robert has dropped out of Yale art school, in New Haven, and Penelope is a former model who’s just left her boyfriend and is searching for a better place to live. Robert pines after Penelope, but his adoration is so passive that the reader is never sure what he wants, or whether he has any hope of being loved in return. “Although he couldn’t understand what went on in her head, he was full of factual information about her,” Beattie observes drily. Penelope occupies herself with waiting for something to happen:

“I know it’s going to be great in Colorado,” Penelope says. “This is the first time in years I’ve been sure something is going to work out. It’s the first time I’ve been sure that doing something was worth it.”

“But why Colorado?” he says.

“We can go skiing. Or we could just ride the lift all day, look down on all that beautiful snow.”

He does not want to pin her down or diminish her enthusiasm.

Penelope wants to flee the East Coast establishment, and yet doesn’t know what she’s looking for: a hero? a husband? or good old American freedom? For Beattie’s characters (unlike, say, Fitzgerald’s or even Hemingway’s) the dream is never really in focus; it’s fogged over by marijuana clouds. When Robert and Penelope finally get to Colorado, there’s no frontier, no beautiful snow, no “lift” (real or metaphorical)—just their friends Bea and Matthew, who are on the verge of breaking up and squabbling over who gets to keep the dog. (In these stories, the most optimistic relationships young people have are with their dogs; it is onto the dogs that all hopeful emotion is displaced.) At the story’s end, Robert, high on pot, asks Matthew, “What state is this?” “Are you kidding?” Matthew asks in response. “Colorado.” In her endings, Beattie mines double entendres for all they are worth. We hear the metaphysical secondary meaning of “state,” and we hear, too, that there’s nothing larger than geography here. Colorado isn’t a new home, or a stand-in for happiness, or any other state of being; it’s just Colorado.

Advertisement

But Beattie’s real accomplishment was not just to capture a generational mood but also to find a fresh way of shaping stories. Most of her stories are what we call an “ensemble piece” in film or theater—typically, no single character is more important than the others. Her main characters, often women, seem almost numbed or distracted by their immediate situation (preparing for a big dinner party, in “The Burning House,” or energetically pretending her older writer-partner isn’t sleeping with his former students, in “Weekend”), an attitude that allows Beattie to focus on what goes on between people rather than inside them, even when she is writing in the first person. She is less interested in exploring interior psychology than in dramatizing the unpredictability of group interactions; the stories move in unorthodox ways, flitting back and forth, sustaining a flashback for three pages of a six-page story.

Frequently, her stories are set in the present tense, perhaps because events taking place in the present can be more persuasively inscrutable to a character than events weighed in retrospect. (There’s only so much aimlessness a reader can handle, after all.) Here, for instance, is a sequence from “Secrets and Surprises,” about a woman newly separated from her husband, and her much younger lover, Jonathan:

I play Scriabin’s Étude in C Sharp Minor. I play it badly and stop to stare at the keys. As though on cue, a car comes into the driveway. The sound of a bad muffler—my lover’s car, unmistakably. He has come a day early. I wince, and wish I had washed my hair.

The characteristic Beattie story is neither defined by a moment of quiet epiphany nor propelled by event, the way a traditional New Yorker short story was. And it rarely uses metaphor or simile—the devices short story writers typically deploy to help the reader grasp emotional undercurrents. Instead, it is stripped down to bare surfaces. In “Snake’s Shoes,” a divorced couple is sitting at a lake together with their daughter and the husband’s brother:

“Look,” the little girl said.

They turned and saw a very small snake coming out of a crack between two rocks on the shore.

“It’s nothing,” Richard said.

“It’s a snake,” Alice said. “You have to be careful of them. Never touch them.”

“Excuse me,” Richard said. “Always be careful of everything.”

The emotional undertones are conveyed through the setting—the pastoral lake, the real (and highly symbolic) presence of the snake. On this weekend, the broken family has come together, but they will soon split apart again. Often, though, the reader has to work to extrapolate the situation and the relationships. The story “Vermont” opens, opaquely:

Noel is in our living room shaking his head. He refused my offer and then David’s offer of a drink, but he has had three glasses of water. It is absurd to wonder at such a time when he will get up to go the bathroom, but I do.

Who is Noel, and who is David, and what are their relationships to the narrator? Since the details aren’t presented in a straightforward way, the reader wonders what “at such a time” can mean. Only as the story continues does it become clear that Noel’s wife has left him.

Because of her sparse indirection, Beattie was quickly labeled a “minimalist”—along with Raymond Carver, Bobbie Ann Mason, and Mary Robison, all of whom The New Yorker regularly published. But Beattie resisted the term. And indeed she was never a minimalist in the sense that Carver was. Carver strived for “brevity and intensity” and found a way to use spare prose to bear down brutally into the emotions in a scene. Beattie deflects emotion ironically, focusing on a mood rather than pushing toward resolution. And so it can be difficult to recall what happens in a Beattie story; the numbed-out feeling is what lingers.

After the publication of her third volume of stories, The Burning House (1982), Beattie’s short work became sparser, even as her characters acquired more material possessions. They are older, wealthier—gone are the days of “Colorado,” when they lacked kitchen chairs; this is the era of the yuppie. In “Janus,” one of her most famous stories, Andrea and her husband have “acquired many things to make up for all the lean years when they were graduate students”—but possession isn’t gratifying, and they remain as disconnected as ever. Andrea, a middle-aged real estate agent, is quietly obsessed with a bowl she uses to help persuade potential buyers that a “house is quite special.” She takes it home at night and finds herself dreaming about it; as she grows more distant from her husband, she becomes more preoccupied by the bowl, which “seemed to glow no matter what light it was placed in.” It is also, no surprise, “smoothly empty.”

In the story’s final paragraphs, we learn that it was a lover who gave Andrea the bowl. He had wanted her to leave her husband—“Why be two-faced?” he asked her—but rather than leap into the unknown, she stayed with her husband, and her lover left her. Now her strongest emotions pertain to a piece of pottery; while she is materially wealthy she is emotionally poor. Beattie expertly sketches the alienation in a marriage, even if the story lends itself too easily to a classroom debate about the function of symbolism. (Beattie has said that she does not think this is one of her best stories.)

A story I prefer, “In the White Night,” is even sparer—a mere three and a half pages—but its world seems far larger. It shows how much Beattie can do with a few lucid details. Carol and Vernon have just had dinner with their friends Matt and Gaye Brinkley, whose daughter is now taking a “night-school course in poetry. Poetry or pottery?” Carol and Vernon’s daughter has died, a fact introduced indirectly; but this choice on Beattie’s part feels appropriate, since even Carol and Vernon have a difficult time comprehending their loss. On this night, returning home, Vernon tells his wife that he feels their friends are “alter egos who absorbed and enacted crises, saving the two of them from having to experience such chaos.” Vernon’s self-denial—after all, it is they who have lost a child—unnerves Carol; she is “frightened…to think that some part of him believed that. Who could really believe that there was some way to find protection in this world—or someone who could offer it?” In the story restraint and fear work powerfully in tandem.

With her studied reserve, Beattie runs the risk of irritating the reader. The world her characters inhabit in the early stories is so muted that it doesn’t seem entirely recognizable. Relationships frequently end without confrontation. Many of the characters are opaque—and almost willfully disconnected from their own feelings. In “Wolf Dreams,” Cynthia is asking herself why she is getting married a third time. Her self-interrogation is superficial, to say the least:

Part of the answer was that she didn’t like her job. She was a typer—a typist, the other girls always said, correcting her—and also she was thirty-two, and if she didn’t get married soon she might not find anybody…. There was no point in asking herself more questions. Her head hurt, and she had eaten too much and felt a little sick….

Critics of Beattie’s work have complained about the “arbitrary” elements of her stories. In The New York Times, Anatole Broyard wrote, “You never know what her people are going to say or do, surprise follows surprise. But in the end, inscrutability proves to be boring.” In a 2011 interview with The Paris Review, Beattie said, defending her strategy, “I think my stories are very determined. I can tell you the reverberation I have in mind for each element in the story. I can’t make you read it that way, but it’s been contrived, and then revised. What is there is intentional.”

But even Beattie’s strongest admirers registered reservations about the “passivity” of her characters. As Margaret Atwood wrote, in an otherwise laudatory review of The Burning House in The New York Times in 1982, “One admires, while becoming nonetheless slightly impatient at the sheer passivity of these remarkably sensitive instruments.” Spending time with The New Yorker Stories, the reader may at points find herself wishing for a different kind of character, less diffident, more willing to engage in argument, extended self-reflection, or political debate. For all the social upheaval in the background, few people here have anything to say about class or race or Vietnam. But perhaps this is the sort of churlish response that’s inevitable when reading any long collection of short stories.

Anyone who picks up The New Yorker Stories will notice how heavily weighted it is toward stories that appeared before 1987. (There are only eight stories from the years 1988 to 2006.) Between 1992 and 2000, The New Yorker published no stories by Beattie, though she published two books of stories, Park City: Selected and New Stories and Perfect Recall.

Looking at stories from this period, it sometimes seems as if Beattie was trying to compensate for deficiencies critics had pointed to all along, and had begun to write longer stories in which she filled in the empty spaces, sometimes resorting to a jaunty tone that rang false. (A strained jocularity has always been the flip side of her terse irony.) In recent years, though, she has settled in to write some of her best work yet—stories that move in expansive new ways.

In fact, one of the most surprising pleasures of The New Yorker Stories is tracing Beattie’s impressive stylistic evolution. The work she has written over the past ten years conjures fleshier visions of domestic life and loneliness than she had previously allowed herself. The writer who began as a radical minimalist now writes lengthy stories that—tart as ever—also contain the kind of connective tissue that critics like Broyard had wished for from the start. Here, for instance, is the opening of “The Confidence Decoy,” the book’s final story:

Francis would be driving his Lexus back from Maine. His wife, Bernadine, had left early that morning, taking their cat, Simple Man, home to Connecticut with her. Their son, Sheldon, had promised to be home to help out when the moving truck arrived, but that was before he’d got a phone call from his girlfriend, saying that she would be flying into J.F.K. that afternoon.

The details of family relations, the business of getting from Maine to Connecticut—all are laid out with almost comic precision, underscoring how entrenched in entanglements the Boomers became as they aged and had families. Contrast it to the opening of “Vermont” and you get a feel for Beattie’s evolution.

Formally, the recent stories may be less radical than Beattie’s earlier work, but they also feel more substantial—full as ever of the old wit, they wrestle more openly with stark, affecting situations of loss, as the characters deal with a parent’s dementia (in “The Rabbit Hole as Likely Explanation”) or the death of a spouse (in “Coping Stones”). The men in “The Confidence Decoy” and “Coping Stones,” alone and heading into their late years, are trying to figure out something about themselves. In “Coping Stones,” Cahill, an aging widower in Maine, discovers that his tenant (who has become a friend) is a child molester. It’s a crushing blow, and after his tenant is put in jail, Cahill reflects honestly on his own life, and his wife’s complaints that he never really “got involved”:

The sadness of family life. The erosion of love until only a little rim was left, and that, too, eventually crumbled. Rationalization: he had been no worse a father than many. No worse than a mediocre husband. That old saying about not being able to pick your family until you married and had your own…

Not everything about Beattie’s work appeals to me—at times it seems overreliant on evasiveness as a vehicle for some vague malaise. A few of the early stories seemed too affected in their non-emotive coolness. But by the book’s end, I had fallen powerfully under the spell of the Beattiesque view of the world; hers is a truly comprehensive achievement. In Beattie’s best stories, what one finds is, as she herself had insisted, not a minimalist vision, but rather a wry, absurd one, suspicious of the false hopes we use to soothe ourselves and keep fear and doubt at bay, and attuned to language as the faulty medium in which we express our missed connections, failing, over and over, to listen to what those closest to us are actually saying.

-

1

The book was conceived not by the editors of The New Yorker, as the title might suggest, but by Beattie herself. As she explained to The Paris Review, she saw a copy of Elaine Showalter’s A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers from Anne Bradstreet to Annie Proulx in the bookstores and learned from it that she’d published thirty-five stories in the magazine over one ten-year period. It occurred to her that collecting them might be a good idea. See “The Art of Fiction No. 209,” The Paris Review, Spring 2011. ↩

-

2

See Jay McInerney, “Hello to All That,” The New York Times, June 4, 2010. In this review of Beattie’s novella Walks With Men, McInerney recalled that when he arrived in New York in 1980, Beattie was one of the two most influential writers at work. (Raymond Carver was the other.) “Just as an earlier generation used to read Hemingway in part to learn what to drink and where to travel, we read Beattie in part to learn what to listen to and read and what to wear,” he observed. ↩