Only when I reached Suq al-Juma, Tripoli’s sprawling eastern suburb of 400,000, three days after the rebels entered the city on August 21, did I feel I was somewhere free of Muammar Qaddafi’s yoke. In contrast to the deserted, shuttered streets elsewhere in the capital, the alleyways behind its manned barricades were a hive of activity. Children played outside until after midnight. Women drove cars. The mosques broadcast takbir, the celebratory chants reserved for Eid, the end of Ramadan, that God is Great, greater even than the colonel. Replacing absent Egyptian laborers, volunteers harvested tomatoes and figs in the garden allotments. The grocer proudly told me that he was really an oil exploration technician, charged with running a store his neighborhood had opened the day of the uprising—August 20—to keep their community fed. Others had dug wells to ensure that water flowed, and used their connections with the local refinery to maintain supplies of gasoline. While its price elsewhere in Tripoli had risen a hundredfold to $7.50 a liter, in Suq al-Juma it was distributed for free.

While the barricades kept out Qaddafi’s regime, they offered its enemies a safe haven from the snipers and other remnants of Qaddafi’s rule; the residents fed rebels homemade Ramadan sweets and washed their clothes. A rebel brigade from Misrata pitched camp in a whitewashed branch of Mohammed Qaddafi’s Internet company, LTT, due to open this summer. A mosque sheltered dozens of pale and dazed inmates, rebels liberated from Tripoli’s complex of political prisons in Abu Salim. The people there helped them bridge their missing years by projecting Arabic satellite television on its wall. (When Qaddafi’s image appeared, a few flung stones at the mosque.) In a school turned makeshift prison, police officers back at work interrogated a motley assembly of suspected mercenaries, saboteurs, and regime militiamen.

Suq al-Juma claims to have been Tripoli’s first neighborhood to rally to Qaddafi’s revolution in 1969, and the first to turn against it thirty-nine years ago. (It is still punished with unpaved streets.) It prides itself on its cohesiveness. Unlike Tripoli’s other suburbs, which are magnets for urban migration, its residents claim descent from families who founded the neighborhood centuries ago. Several suburbs responded to the alarm the mosques sounded as the faithful broke their fast after sundown on August 20, but the organization and scale of Suq al-Juma’s uprising was unmatched. Within minutes, the entire district had cobbled together barricades out of old fridges, burned-out cars, and other war detritus, and stationed armed men at its gates. Trucks drove through the streets distributing homemade Molotov cocktails and grenades called gelatine, and, later that night, guns they had bought over the previous six months at 3,000 dinars apiece. Based on a precompiled blacklist, vigilantes broke into the homes of a thousand regime henchmen, or farment, Tripoli’s bastardized vernacular for “informant,” and disarmed them and hauled them away.

Across town, the suburb of Dareibi showed a different face. Its uniform concrete apartment blocks are full of rural migrants drawn from all over Libya. Shops remain shuttered despite a week of rebel rule. The residents’ prime means of livelihood and even security have vanished with the regime, and they are struggling to establish a local order in its place. Few trust their neighbors, or have much good to say of them. They lack the bonds born of collective suffering that the colonel inflicted on the eastern part of the country. Some are from tribes that opposed the rebel advance in Misrata, Zliten, and other cities and, when they lost, fled to Qaddafi’s capital in an effort to retain their patronage. Others are more obviously protégés of the regime. In nearby Abu Salim, “revolutionary committees” who acted as Qaddafi’s shadow executive erected their own barricades, waging urban battles with the rebels. Fresh graffiti along the main street declares, “We are all Qaddafi.”

I arrived in Tripoli as rebels laid siege to Qaddafi’s inner sanctum in Bab al-Aziziya. I had yet to discover Suq al-Juma’s warmth and spent my first night in Dareibi with the Berbers who had offered me a ride from the Nafusa Mountains above Tripoli’s coastal plain, and who in normal times worked in the capital. Preferring not to stay in their flat alone, I joined them on their plunder of an abandoned arms depot on Airport Road.

Losing courage at the gates of the stifling warehouse crammed with sweaty scavengers, I slunk back through the darkness to their car. Stopped by teenagers on their way in, I recalled the standing ovation the eastern town of Beida gave to foreign journalists when we turned up after they cast the colonel out, and said I was one. A kid reacted by pulling a knife, and having frisked me he humiliatingly made off with my mobile phones.

Advertisement

Showered with legitimacy abroad, the National Transitional Council (NtC) seemed in its first days to be having a harder time asserting itself in its proclaimed capital. Still, in contrast to Iraq’s forced regime change, Libya’s has much going for it. Its new rulers are Libyans, not foreigners, and though NATO supported the rebels from the skies, on the ground they liberated themselves. In contrast to the weeks that followed Baghdad’s takeover, when American soldiers idled while residents looted, Tripoli’s rebels are already policing themselves. The NTC announced a local municipal government within four days. Apart from the pillage of Qaddafi’s compound and arms depots, the capital is largely unscarred. Unlike in Baghdad, Western fighter jets refrained from bombing the ministries. And while Iraqis stripped Saddam’s palaces, the rebels turned the ruling family’s mansions into museums. Families dutifully piled into Aisha Qaddafi’s house, leaving the books on their shelves and the crockery laid for twelve on the dining room table (although I spied a grandmother sneaking a pair of pink baby bootees into the folds of her dress when a volunteer warden turned his back).

Iraq’s zealous debaathifiers stripped the state of its public sector down to the traffic wardens. Libya’s incoming rulers profess to be more inclusive, and have appealed for all but a thousand government personnel to return to work. And by the seventh day, policemen were reporting for duty. Crucially, the rebel leaders also came armed with a seventy-page Tripoli Plan for stabilizing the city under their aegis—the kind of plan the State Department drew up and the Pentagon discarded in Iraq.

All told, the road back to normality appears uncannily quick. Supermarkets opened followed by clothing shops, to prepare for the Ramadan holiday. Taxis returned to the streets followed by traffic police, and gasoline began to trickle back to the gas stations. There were even traffic jams. After nearly ten days, the banks reopened their doors. Apparently recognizing that the tide had turned after rebels repeatedly overwhelmed them in gun battles, fighters from the Abu Salim district—at least temporarily—put down their arms.

But there are also less welcome similarities. The colonel and his sons, like their Iraqi counterparts did for months, remain at large, threatening to stoke an insurgency by denouncing Tripoli’s conquerors as NATO lackeys. Some fighters have adopted the colonel’s own catchphrase, declared at the start of his counterattack, to track him down: “House to house, alley to alley, zanga, zanga.” But the plethora of rumors regarding his whereabouts suggests that his pursuers have few concrete clues. Rebels scouring the city’s tunnels and sewers have resurfaced without al-jurathan, or rats, the term Qaddafi once used of them.

Others suggest he may have fled up the Great Man-Made River, a complex of underground steel pipes big enough to transport vehicles from the Sahara to the coast. Yet other reports claim that he has fled to Bani Walid, a town some 170 kilometers east of Tripoli where the still-loyal sheikhs of the Warfalla, Libya’s largest tribe, have their stronghold. Israelis of Libyan origin fancifully suggest that he might seek Israeli citizenship based on the Jewish grandmother the rumor mill credits him with.

Despite his retreat, a central swathe of Libya still lies in his hands, continuing to sever the two rebel flanks. From Sirte on the coast to Sabha, a garrison town 650 kilometers to the south, the buffer is home to powerful tribes—including his own—that provide the mainstay of his security forces, and its Saharan roads could yet serve as conduits to bolster his forces with African mercenaries. Intermittent, albeit decreasing, sniper fire in the capital, too, reminds Tripolitans pondering switching sides that while Qaddafi is no longer visible, his militiamen may still lurk. Fears are widespread that his brigades, which seemed to vanish, could yet emerge as a tabur khamis, or fifth column, in the heart of the capital.

Insecurity and the fears that accompany it have delayed rebel attempts to reclaim the streets. No sooner had their vanguard of civilian representatives arrived from Tunisia than the threat of counterattack forced them to beat a retreat. “We’re overexposed and our presence is endangering your safety,” explained Mahmoud Shammam, before quickly leaving their first stop, the Radisson Blu in central Tripoli, where journalists had been staying. Plans for celebratory prayers on the last Friday of Ramadan in the capital’s central Green Square, the source of many a raucous rally under Qaddafi, were put on hold, and fear of snipers kept worshipers from straying out. Hisham Buhajiar, one of the rebel commanders assigned to pacify the capital, estimates that he has just 2,000 of the 15,000-strong taskforce that the Tripoli Plan says he needs.

Advertisement

Even a decisive victory over the colonel, moreover, gives no guarantee that the NTC can set up a workable regime. The longer Libya’s would-be civilian rulers dither over showing their presence, the greater the risk that others will fill the political vacuum. Some public employees may yet wait awhile to see which way the wind is blowing before heeding the calls to return to work. When a senior official at the Religious Affairs Ministry turned up at his office building, he found the doors locked.

The degradation of utilities in the first week of rebel rule leaves a further question mark hanging over the NTC’s ability to translate revolt into government. Supplies of electricity for the Internet and the cell phone network have worsened rapidly, and the city’s water has run dry. Though officials blame sabotage to the water supply in Qaddafi’s stronghold 700 kilometers to the south, the superstitious see a link between the fate of the Great Man-Made River and its creator. In the hospitals, the nursing staff was largely comprised of foreigners, who have fled. With medical facilities overwhelmed, the wounded were often left to die and putrefy in their beds. Cadavers lay strewn alongside piled-up rubbish.

As in Iraq, the aftermath already looks like a more arduous task than the rapid military campaign. Confounding Qaddafi’s efforts to pit Arab against Berber, east against west, and Libyan against foreigner, Tripoli’s takeover was a model of unity and combined planning. Displaying rare synchronicity, NATO bombers struck loyalist bases, rebel forces swept down from the mountains to the coastal plain as well as west from Misrata, and disaffected Tripolitans finally mounted their much-anticipated implosion from within.

Mahmud Turkia/AFP/Getty Images

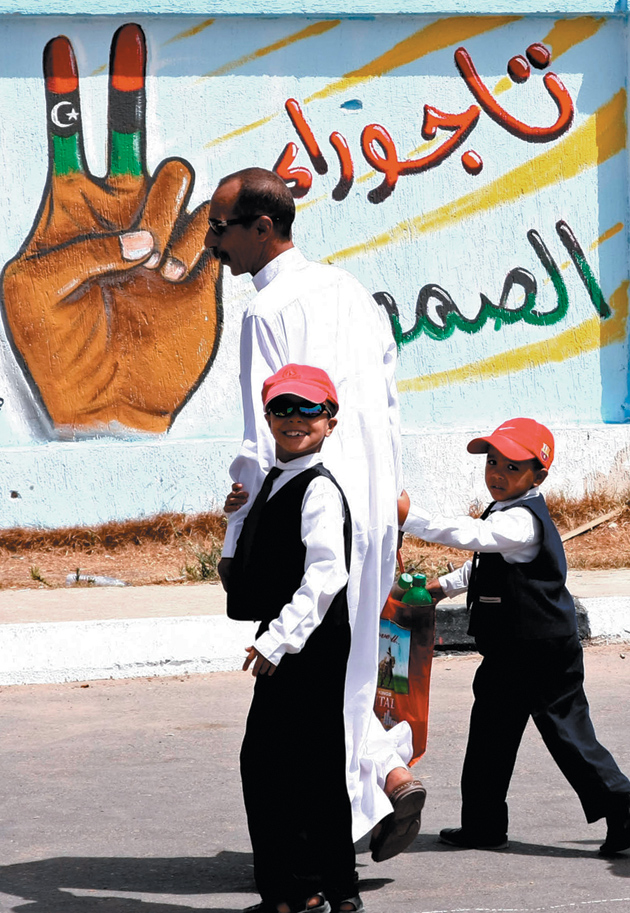

A Libyan man walking with his children in their new outfits on September 1, celebrating Eid, the end of Ramadan. The top line of the mural next to the fingers showing a V for Victory refers to Tajoura, a Tripoli neighborhood that rose up early in the conflict but was crushed. The cut-off bottom line probably uses the word al-Sumoud, meaning steadfastness or endurance.

Hatched in capitals across Europe and the Arab world, as well as in rebel operation rooms secretly organized in Libya itself, the military campaign took four months of planning. In May, exiled opposition leaders abandoned their jobs as lecturers in American colleges and established an intelligence-gathering bureau on Djerba, the Tunisian island across the border from Libya. Led by Abdel Majid Biuk, an urbane mathematics teacher from Tampa, Florida, the team interviewed four hundred Qaddafi security officers who defected following the loyalist defeat in Misrata; using Google Earth, they analyzed the colonel’s defenses. “We went through the whole city building by building to ascertain its fortifications,” Biuk told me on his arrival in Tripoli.

He passed the data on to a military operations room elsewhere on Djerba whose staff included representatives of NATO and Gulf allies as well as Libyan army veterans who had defected to the US and formed the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL), an opposition group that led a series of aborted coups in the 1980s and 1990s, before branching into website campaigns. Under the eyes of Tunisian customs officials, they smuggled satellite phones, which are banned in Tunisia, in ambulances across the border into Libya, and set about supplying the rebels. Chevrons were daubed on a straight stretch of road at Rahebat in the Nafusa Mountains, turning it into a landing strip. Military supplies began arriving by the planeload, including 23-caliber tank-piercing bullets.

Tunisia provided a conduit for fighters as well as arms. With Qaddafi’s continued control of the center of the country blocking access over land, Benghazi volunteers took a circuitous route, flying from Egypt to Tunis, before crossing the border at the Tunisian town of Dehiba into the Nafusa Mountains. By mid-August they had established five brigades each with its own mountain training base, and together formed a two-thousand-man battalion under Hisham Buhajiar’s command as well as that of Abdel Karim Bel Haj, a Libyan veteran of the Afghan jihad. Trainers included NFSL veterans. Younger Libyans raised in the US, including the son of a Muslim Brotherhood activist from a US-based company, provided close protection. As they prepared the final stages of their assault, a host of Berber irregulars drawn from towns across the mountains jumped on board. Meanwhile, a collection of local traders, engineers, students, and the jobless from Misrata, battle-hardened by their seventy-day defense of their city, reassembled their brigades and prepared to join the attack on Tripoli from the east, by both road and sea.

Finally, the planners on Djerba divided Tripoli into thirty-seven sectors, and appointed local security coordinators to recruit, train, and arm local cells, using Muslim Brotherhood leaders to bless an armed uprising. “Our first slogan was ‘no’ to the militarization of the intifada,” says Ali al-Salabi, a Muslim Brotherhood politician in exile who worked with the planners, and who was among the first to arrive in Tripoli after Qaddafi’s inner sanctum fell. “But after protesters were gunned down, we realized armed revolution was the only way.”

Among the gunrunners was Salima Abu Zuada, a twenty-six-year-old legal adviser at Qaddafi’s Transport Ministry, who had learned to drive tanks as part of her high school military training. After fleeing to Tunisia in April, she made eight trips by road and tugboat, smuggling hundreds of guns and rocket-propelled grenades back to Tripoli. “Qaddafi didn’t suspect us,” she says. “He thought all women loved him.” Qaddafi’s intelligence chief, Abdullah Senussi, was more wary, however. On two occasions his spooks in Tunisia, she says, tried to run her off the road.

On Saturday, August 20, as dusk descended and the mosques sounded the prayer call for breakfast, Mustafa Abdel Jalil, Qaddafi’s meek-seeming former justice minister who now heads the NTC, went on television to deliver an address. Before he had finished, the rebel flag was flying over Suq al-Juma and other Tripoli neighborhoods. Meanwhile, NATO forces intensified their bombardment of loyalist positions on the western outskirts of Tripoli, stretching to its limits their UN mandate to protect civilians. As the colonel’s forces abandoned their bases, they found themselves sandwiched between rebels sweeping in from the mountains and Tripolitans carving out their own enclaves. Challenged on multiple fronts, Qaddafi’s forces melted away.

The speed of the conquest may yet contain the seeds of its disintegration. Without a common enemy, the diverse opposition could quickly unravel once its composite parts start jostling over the spoils. Already each of the participating groups is leveraging the instrumental role it played in the victory to promote its own interests. Despite earlier protestations that they had no troops on the ground, NATO officials have begun leaking laudatory details of the part played by their special forces in supporting the rebel army. So too have Arab states such as Qatar; and not to be outdone, Turkey has released details of its hundreds of millions in cash handouts to the rebels in the hope that the NTC might both honor the huge contracts Qaddafi gave Turkish construction companies and include Turkey in postwar reconstruction.

United in war, many leading rebels have begun circulating competing narratives of the importance of their respective parts in the operation. The US professors sped to Tripoli from Djerba as soon as the capital fell, claiming that they were the architects of the victory. Some, overcome by the emotion of returning to Tripoli after thirty-five years, broke down in tears before the harsher reality dawned that locals were after the jobs they had prized on the grounds that they had gotten rid of the regime. The Berber fighters who swept down from the mountains underscored their role by daubing the Berber symbol of two back-to-back tridents on the capital’s walls, cars, and barricades. The four-thousand-strong Misrata Brigades took to Tripoli’s central square, firing their antiaircraft guns through the night, lest anyone forget their presence and pugnacity in marching on Tripoli independently of any command on Djerba.

All made a show of unity when the first senior NtC representative, Finance Minister Ali Tarhouni, arrived in Tripoli from the rebel base in Benghazi. But no sooner had they joined him on stage for a press conference than fresh fractures emerged. Beneath the chandeliers of a hotel ballroom, Tarhouni forgot to include the Tripolitans in his long list of gratitude for those at home and abroad who had chased Qaddafi from the city. “He didn’t appreciate the role played by the intifada,” said an irate member of the new Tripoli council, who retired to the back of the ballroom where Tarhouni was speaking.

Giving vent to suspicions that eastern Libya might yet seek to upstage the west, the council member added, “If he thinks he can tell the people who liberated their city to lay down their arms, he’ll be sent packing.” Some are clearly keen to disarm, regardless. Dressed in a black chador with gold-sequined sleeves, Abu Zuada, the female gun-runner, played with the shiny baubles she had stuck on her mobile phone and spoke of returning to her office at the Transport Ministry. But others might find the adjustment more cumbersome. Libya has little tradition of warfare, but, clearly frazzled by the profusion of weapons, preachers in mosques have issued calls for Libyans to register all of them. With Libya’s multiple rebel forces asserting control over overlapping enclaves in the city, and with the linchpin that united them out of government, it is not clear who will rule in, and from, Tripoli, and how. New forces of regionalism and Islamization, represented by different if not rival militias, are beginning to elbow for power. Libyans may yet face a bumpy succession.

—Tripoli, August 29, 2011

This Issue

September 29, 2011

School ‘Reform’: A Failing Grade

Coming Attractions

After September 11: The Failure