Teach us to care and not to care

Teach us to sit still

Even among these rocks….

—T.S. Eliot, “Ash-Wednesday”

In 1971, forty-year-old Ram Dass, formerly Richard Alpert of Harvard University, published one of the most widely read and influential “wisdom” books of the twentieth century, whose message is, more or less, wholly contained in its imperative title—Remember, Be Here Now. In his earlier incarnation as Alpert, the author had had teaching and research positions in psychology at Stanford and Berkeley as well as Harvard, where he’d been a collaborator and close friend of Timothy Leary; in 1963 both Alpert and Leary were dismissed from Harvard as a consequence of their controversial laboratory experiments, which included undergraduates, with LSD and other psychedelic drugs. Following a spiritual pilgrimage to India in 1967, about which he writes in Remember, Be Here Now, Alpert was given the name “Ram Dass” (“servant of Lord Rama”) by his Indian guru, launching him upon a lifetime of charismatic “spiritual leadership.”

It isn’t irrelevant to note that along with his elite academic credentials, Richard Alpert was the son of a wealthy Jewish lawyer named George Alpert, not only president of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad but a founder of Brandeis University and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. What more symbolic repudiation of an entire way of life—ambitious, materialist, competitive, highly “successful”—than Alpert’s rejection of his identity and his establishing of himself, in the spiritually impoverished decade following the end of the Vietnam War, as “Baba Ram Dass,” the most mystical of American countercultural leaders?

Tim Parks’s engagingly intimate and often very funny Teach Us to Sit Still, a memoir of the British author’s journey from debilitating and depressing pain to spiritual “enlightenment” in 2006, covers much of the psychological terrain of Remember, Be Here Now and comes to a virtually identical conclusion about the need to experience “things as they are,” while making no mention of the 1971 book at all—a suggestion that “wisdom” books don’t cross borders readily. Ram Dass continues, according to his website, to pursue a “panoramic array of spiritual methods and practices from potent ancient wisdom traditions,” and he works with the Love Serve Remember Foundation and other groups organized to continue his teachings.

Parks, a quintessentially “literary intellectual,” could hardly seem more different. He has written fourteen well-received novels, seven works of nonfiction, including books on Italian soccer and Medici Florence, and numerous reviews in the London Review of Books and in these pages; he is a distinguished translator of such books as Roberto Calasso’s Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony and novels by Moravia, Calvino, and Tabucchi and teaches translation at the Independent University of Modern Languages in Milan; he even has “bowed” shoulders—“This goes with the writer’s profession.” His revered touchstones aren’t Hindu mystics or Sixties gurus like Timothy Leary (“Turn on, tune in, drop out”) but Melville, Coleridge, Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence, T.S. Eliot, and preeminently Samuel Beckett. (“I had fallen in love with Beckett. He seemed a man inoculated against all religion.”)

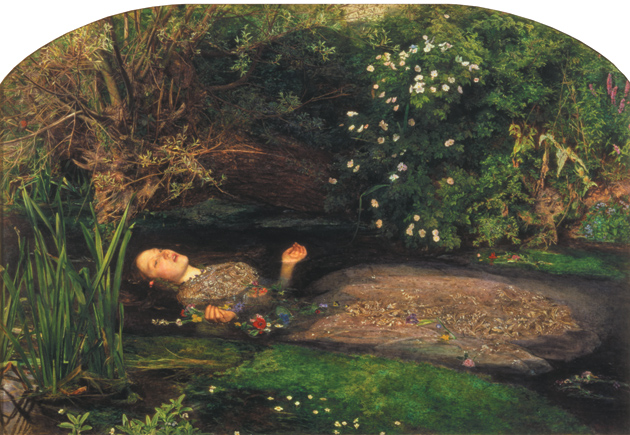

In the desperation of his physical misery, chronic and inexplicable pain in the region of the pelvis diagnosed as “prostatitis,” which no medical remedies can cure or even satisfactorily explain, Parks turns to classic works of art that appear to hold “some obscure message” for him—paintings by Velázquez, Magritte, Millais, Doré, and Cézanne. The drollery of his occasional, mysteriously mundane images, reproduced in small plates within the memoir’s text, suggest the enigmatic visual images inserted in the texts of W.G. Sebald’s memoirist novels of post-Holocaust paralysis.

There’s nothing remotely New Age about Tim Parks’s dryly dyspeptic prose: “I had begun to envy people who were indisputably ill. I wanted to be seriously, seriously ill myself, so that people could see my condition and it would all be out in the open and someone would finally have to do something.” And, “In literature too, I’m convinced, a clear-sighted pessimism is always more exhilarating and liberating than soft soap and denial.” Yet Parks’s journey from the “stupid pains,” which can be seen as a physical analogue to the boxed-up and claustrophobic “ego” of Richard Alpert before his conversion, parallels Alpert’s journey more than four decades ago: both men, intellectuals by temperament as well as by training, learn that they must throw off the shackles of the analytical mind:

The heart surrenders everything to the moment. The mind judges and holds back. (Ram Dass)

The only way to force an irreversible change in my life would be to dump the project that had been driving me, goading me, making me ill, I decided, for as long as I could remember: the WORD PROJECT. If illness is a sign of election in a writer…then renouncing writing might be a necessary step to being well. (Tim Parks)

Both men’s books even include “art” of a kind—mystic drawings and illustrations in Remember, Be Here Now, photo plates in Teach Us to Sit Still.

Advertisement

For Ram Dass, salvation is summed up in the terse admonition be here now. Tim Parks describes salvation as the realization that, by using language, he has been avoiding a confrontation with “naked, unmitigated, unmediated reality…. Perhaps it was time, then, for me to face up to that: the simply being here, instead of taking refuge in writing about being here. I must go speechless.” This realization reminds him of a lesson taught by his Buddhist instructor, “an aging American, John Coleman”:

Guru Coleman, I felt, was trying to tell us something similar in his evening talks. The most immediate reality, the only reality to which we had access at every moment of our lives, the fat man said, was the breath, this breath, this instant, crossing our upper lip as it went in and out of our lungs. The breath, not our breath. Everything else was empty imagining.

Fortunately, the evidence of Teach Us to Sit Still suggests that the “enlightened” author wasn’t speechless for very long.

Despite the high-churchiness of the solemn quote from T.S. Eliot that provides the book’s title, suffused with the poet’s elegiac abnegation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, Parks’s memoir is anything but churchy, preachy, pious, or pontifical. Stricken in his forties with a protracted and mysterious pain and with a humiliating need to urinate frequently during the night, Parks gradually suffered a kind of “deterritorialization”—a sense that his chronic pain was forming “a shell around me” and that his personality was being altered by his condition. A young doctor gives him a booklet in which he reads that “Prostatitis sufferers tend to be restless, worrisome, dissatisfied individuals”; the doctor, he writes, implied that “personality and pathology were related.“

Teach Us to Sit Still is a precise accounting of how Parks broke free of the extremely painful “headache in the pelvis” that had come to dominate his life. Virtually each of its pages concentrates upon delineating the author’s “stupid pains” and his reactions to them—rationalizing, despairing, denying, obsessing:

I had quite a repertoire of pains at this point: a general smouldering tension throughout the abdomen, a sharp jab in the perineum, an electric shock darting down the inside of the thighs, an ache in the small of the back, a shivery twinge in the penis….

Parks endures a battery of blood and urine tests, all inconclusive: “The urogram is one of those medical tests of which one says, if you’re not feeling ill before, you will be afterward. But I was feeling ill before.” He becomes obsessed with his condition, which he feels he must keep secret: “Illness, I realized then, like love, or hate, draws everything to itself, turns everything into itself. Whatever I thought about came back to that: my condition.”

Disappointed by the doctors whom he sees, Parks takes advantage of a translation conference in India to see an Ayurvedic doctor—a practitioner of the Indian medical system that seeks to harmonize body, mind, and spirit—who tells him bluntly, without having examined or tested him: “This is a problem you will never get over, Mr. Parks, until you confront the profound contradiction in your character…. There is a tussle in your mind.” The “tussle” is the consequence of a blocked vata; such a “tussle” isn’t about anything but is “part of the prakruti,” which is defined as “the amalgamation of inherited and acquired traits coming together to form the personality.” Parks doesn’t reject the Ayurvedic diagnosis, which he interprets as a suggestion that his illness is “psychosomatic”; he’s at a loss about what to do with such a diagnosis, and returns to his Italian doctor for a cystoscopy that reveals that, for all his continued pain, his bladder is “clean as a baby’s.” Yet a few hours later, he experiences “the most excruciating pain I have ever felt.”

Parks turns to the Internet, only to discover a nightmare cacophony of conflicting information and ghastly first-person accounts of prostatitis sufferers. Yet on the Internet he discovers an American self-help book unpromisingly titled A Headache in the Pelvis by David Wise and Rodney Anderson—“Together they had the ring of a charlatan double act dreamed up by Mad magazine.” Despite Parks’s skepticism he finds himself impressed by the authors’ insight into his condition:

Advertisement

“The effect on a person’s life…has been likened to the effects of having a heart attack, angina, or Crohn’s disease…. Sufferers tend to live lives of quiet desperation.” Depression, anxiety, and “catastrophic thinking,” they said, were the norm.

Parks’s self-preoccupation, coupled with his nighttime miseries and intruding memories of an unhappy childhood as the (skeptical, rebellious) son of an evangelical Anglican minister whose life’s work was “to assert, assert, assert, to keep the 2,000-year-old faith,” pushes him toward mental collapse: “I was going nuts. The truth is we know nothing about our bodies, I thought. Nothing. What’s in there, what’s going on?”

His self-doubt includes his writing, which seems to him a secular version of what his anxious father did in writing sermons for each Sunday’s service: “Do I try to write stories, I wondered, because in general I have such a weak grip on the story of my own life?” Is there something flawed in narrative-making, as in the very nature of language?

Each research paper contradicts the next. Every discipline is a scathing of the others. A second opinion. A third. The Web is an ocean of confusion. Above all, every story told in words, every medical story in particular, is always a thousand times clearer than reality. However unhappy, narrative is, of its very nature, reassuring, gives the illusion of knowing, when all anyone ever really knows is how he’s feeling now, now, now and now, in this instant.

It’s only when Parks takes up the discipline of “paradoxical relaxation” recommended in A Headache in the Pelvis that he begins to acquire some control over his pain; he’s astonished to begin to experience sensations in his body that are new to him, and best expressed in passages from D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, which he’d previously dismissed as Lawrence’s “pompous pseudospiritual psychodrama.” He is made to realize that his physical being is a “wreck”—“a bundle of twitchy nerves, poor posture and bad habits” in a constant state of anxious tension provoked by a “constant chatter in my head.” Learning to be “still and perfect”—an ecstatic state described in Women in Love—now becomes Parks’s goal.

This realization is the approximate midpoint of Teach Us to Sit Still: the turning point of Tim Parks’s life as a “sufferer” and the start of his life as a person determined to take control of his suffering through meditative disciplines like “paradoxical relaxation” and a series of spiritual retreats—not to exotic India like Richard Alpert but to monasteries in Italy. (Parks has long lived in Italy, near Verona, with his Italian wife and three children; significantly, he’d left England shortly after his father’s death.)

He never entirely loses his dyspeptic edge. When he tries the foot therapy called shiatsu, administered by a former dressmaker in Verona, the inane blaring talk show from the radio of a dietitian next door makes it impossible for him to relax. “This is costing me fifty euros, I thought…money thrown away…. I needed silence.” He then goes to an allegedly secluded monastery in Tuscany where he’s forced to overhear, at a little distance, nuns in a nearby convent cheering Italian athletes whom they are watching compete on TV: “If there is one thing I loathe, it’s the Olympic Games, festival of empty pieties, crass patriotism and sophisticated performance drugs.” Earlier he tries a form of meditation called Vipassana—“self-purification by self-observation”—and feels his body respond with “pleasurable” sensations, but becomes briefly fed up:

These varied reactions, our teacher tells us, are manifestations of anicca, which is to say, the constant instability of all things. He invites us to contemplate anicca. To know anicca, the eternal flux, in our hands, our chests. To recognize that nothing is fixed. Ego, identity, they have no permanence.

Immediately, my thinking mind rebels. My determined self rebels. Who needs this mumbo-jumbo…. Who needs this theory?

But in its second half Teach Us to Sit Still also lapses into the kind of detailed accounting of meditative sessions that has become the familiar stuff of so many self-help “inspirational” books from Ram Dass onward. Unless one is a poet of sharp-chiseled images and original metaphors like Gary Snyder, Robert Bly, Chase Twichell, or Jane Hirshfield, so steeped in the meditative wisdom of Zen Buddhist mysticism that it has become a second language, it’s difficult to write well about mystical experiences, or even submystical experiences of the sort that occur during protracted meditative sessions:

There was now a stabbing pain right between the shoulders. It was ferocious. Stab, stab, stab. Bizarre lights and burning heat radiated out from it. How could I be in so much pain when I knew there was nothing at all wrong with me? What was I learning from all this, I wondered? Nothing. Nothing except that every single thought that rose to my mind was in some way self-regarding. No, in every way self-regarding.

As happy families are said to be all alike, so Zen masters, Hindu gurus, and self-help healers of the most diverse species tend to sound alike; the vocabularies differ considerably, but the goal is identical: “enlightenment,” “purification,” “liberation from the ego” or, in Parks’s particular case, liberation from the pain of the “headache in the pelvis.” The problem with self-help/inspirational books, even when they are intelligent and well-written like Teach Us to Sit Still, is that they follow a familiar course, and bring us to a familiar place where language is ancillary to sensation:

We’re fascinated by words—but where we meet is the silence behind them. (Ram Dass)

One renounces any objective but the contemplation itself…. You are here to be here, side by side with the infinitely nuanced flux of sensation in the body. (Tim Parks)

One might argue—using some of Parks’s other work for evidence—just the contrary: that it’s our human capacity for being in one place while having the mental capacity to imagine another place, as we have the mental capacity to recall the past, learn from it, and calculate the future; that is our species’ exceptional talent. All of civilization—tradition, art, law, domesticity—is the consequence of never being exclusively here, now but having the conscious ability to be there, then.

The more impassioned a memoir, the more it is likely to exclude much of the memoirist’s life. Teach Us to Sit Still is so quirkily cranky a book, its narrator so maddeningly self-focused, that it’s startling to learn that he is married and has children; although he’s earlier written books about his family life in Verona, we catch only blurred glimpses of them from time to time, like figures swiftly passing the wrong end of a telescope, and have not the slightest idea of how the personality delineated in the memoir could interact with others in a domestic household. And it is a total surprise, for this reader at least, to be told in one of the last chapters that Parks isn’t skeptical, cynical, or pessimistic at all, like his hero Beckett: “Precisely the problem for me is that life is so beautiful. I am very attached to it. My misery when I was ill was only in part the pain. More important was losing beauty, being unable to enjoy.”

The American Buddhist John Coleman—“on his last legs, shuffling, pushing eighty, fat, sometimes fatuous”—is the most touchingly drawn portrait in Teach Us to Sit Still. Though Parks tries to take a skeptical view of this guru it’s clear that he feels intense ambivalence for Coleman, as he feels for his late, “charismatic” minister-father:

It was as if Coleman, Coleman’s voice, were able to command those waves of release I had come across so unexpectedly in paradoxical relaxation. He commanded and I let go; a strange fluid rushed in, rigidity dissolved.

It’s a poignant irony that, at the conclusion of the retreat, Coleman simply reads to the meditation room those Bible verses concerning charity—“St. Paul’s great hymn to charity. Being read by a Buddhist”—that Parks’s father revered. Of course, Parks is made to realize that he’d never actually listened to the words before in his father’s church: “For now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.”

Teach Us to Sit Still ends on the upbeat note with which it begins in the author’s foreword, with Parks speaking of having been shown “a way back to health.” But what of the abiding love for Samuel Beckett? Parks sets beside the incantatory words of Saint Paul the harshly funny colloquialisms of the twentieth-century visionary of dark spaces:

The Tuesday scowls, the Wednesday growls, the Thursday curses, the Friday howls, the Saturday snores, the Sunday yawns, the Monday mourns, the Monday morns. The whacks, the moans, the cracks, the groans, the welts, the squeaks, the belts, the shrieks, the pricks, the prayers, the kicks, the tears, the skelps, and the yelps….

Teach Us to Sit Still is a moving self-portrait of a mind/body in perpetual “tussle”: drawn to the stasis of spiritual enlightenment but powerfully attracted as well to the Beckettian contrary. Parks’s skepticism is a healthy corrective to a too-happy resolution of such tension: “Life is so much longer than any of our enthusiasms.”

This Issue

September 29, 2011

School ‘Reform’: A Failing Grade

Coming Attractions

After September 11: The Failure