Unlike the no less challenging civilizations of East and South Asia, the world of Islam suffers from having been a charged opposite to the West. Ever since the seventh century CE, when Muslim armies first spread with baffling ease across the southern Mediterranean and the Middle East, Islamic civilization has been viewed, in Europe and in America, as shot through with an eerie sense of grandeur tinged with menace. The threat posed by Muslim powers on the frontiers of Europe was sharpened by the feeling that Islam itself was not entirely alien. It was seen as a mutation from the common stock of Judaism and Christianity that was all the more disturbing because the family resemblance between the three religions had not been entirely effaced. This attitude has persisted into modern times.

As a result, this major civilization, close to Europe in more ways than one, has been regarded by many as more than usually inaccessible. The beauty of its art, however, has always had its admirers, both in Europe and in America. The Aesthetic Movement of the later nineteenth century, which prized beautiful objects regardless of their time and origin, reached out to the decorative arts of Islam. One of the first donors to the Islamic collection of the Metropolitan Museum, Edward C. Moore, was the chief designer at Tiffany and Company from 1868 to 1891.

Not all collectors were aesthetes. A robust contributor to the Islamic collection of the Metropolitan Museum, James Franklin Ballard (1851–1931), was a manufacturer of patent pills from St. Louis, Missouri. In middle age he developed a passion for Oriental rugs. He knew North Africa and the Middle East. He traveled 47,000 miles in those regions. He happened to be present at the opening of the tomb of Tutankamen; he also happened to be put in prison briefly by the Greek government. He witnessed the terrible burning of Smyrna in 1922. By modern standards, he held old-fashioned views on the Orient. But his heart was in the right place. He knew what it was to seek out beauty:

It would seem to me that every man or woman should have a “hobby” of some kind—something sufficiently interesting to make it possible to forget, for a time, the everyday cares and worries and get the mind into a new environment. A complete change of thought is both restful and refreshing.

It is as good a motto as any with which to visit the new Islamic galleries of the Metropolitan Museum, which opened at the beginning of November and have been completely renovated, expanded, and reinstalled.

In the case of the Morgan Library, the core of the collection of manuscripts from the Islamic world was first purchased, in 1911–1912, by J. Pierpont Morgan at the urging of his remarkable head librarian, Belle da Costa Greene. This initiative had been the result of a joining of hearts. Greene and the art critic Bernard Berenson had come together at the great Munich exhibition of Islamic art in 1910. It seems that both shared in the thrill of the discovery of so much beauty in what was, for each of them, a new and hitherto alien world. The result was a collection of unique pieces that was magnificently catalogued in 1997.1

But how can this discovery be made to happen today? For the Morgan Library it is a relatively easy task. The exquisite painted manuscripts in the collection can be trusted to tell their own tale. We enter a single exhibition room, with great manuscripts of the Koran placed in the center, flanked by other manuscripts produced in late medieval and early modern Iran and in Mughal India. Here we are shown two things: the stark spine of a world religion condensed in the Korans, and then, around them, the imaginative heritage that flourished beside the Koran like a great magic forest.

It is a forest of many avenues that reach in many directions. We can go back to the centuries before Islam, through Persian tales of pre-Islamic rulers, among them Alexander the Great, in the illustrations of the Shahnama—Book of Kings—of Firdausi (940–1020) and in the courtly tales of Nizami (1141–1209). We can look out across Eurasia, through scenes set in Persian renderings of Chinese landscape painting. We can look over the western boundaries of the Islamic world, by following the life of the great poet Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī of Konya (1207–1273), a mystic perched on the frontier with Byzantium. His Sufi music entranced neighboring Christians and his love of God found room for all faiths. In one miniature we meet the figure of Jesus, his head wreathed in the flames that marked him out as a prophet acclaimed by the Koran.

Passing along the walls devoted to the miniature paintings of sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century Iran and India, we can feast our eyes on a series of portraits of dreamy young men and women and of worldly-wise courtiers as full of character as were the Western miniatures of their contemporaries Clouet or Nicholas Hilliard. They were drawn in courts that were as magnificent and as diverse as any ruled by François I or Queen Elizabeth. The Morgan exhibition is a worthy tribute to the opening of the heart and mind to different worlds, first provoked by the enthusiasm of Belle da Costa Greene and her circle.

Advertisement

The curators of the Islamic collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art have faced a different and more challenging task: how to do justice to an entire galaxy of cultures touched by Islam, which spread from the Atlantic to South Asia and the borders of China, and which changed constantly over the course of a millennium. In this immense galaxy, the arts of late-medieval Iran and Mughal India, displayed in the Morgan Library, are no more than a single, incandescent cluster. The curators have displayed the changing galaxy with an intellectual determination and with a visual discretion that make their new installation a delight to the eye and their meticulous new catalog a thrill to the mind.

First of all, the galleries now bear a distinctive name. They are the New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. It is a mouthful. But behind the title lie decades of careful thought on the relation between the universal and the particular across a far-flung commonwealth of cultures. The notion of Islamic art as a single, uniform system that spread with monotonous insistence across the territories ruled by Muslims is effectively dismantled. The essays of the four editing curators, Maryam Ekhtiar, Priscilla Soucek, Sheila Canby, and Navina Najat Haidar (along with the other contributors), make this point clear. The galleries have been reinstalled with the express purpose of doing justice to the distinctive flavor of each region.

It is not often that an intellectual contention is turned into a work of beauty in itself. But this is what Michael Battista and his fellow installers and designers have done with the layout and décor of the new galleries. Their work has allied itself with the discreet, almost subliminal beauty that radiates from the objects themselves. Lattice screens, made for the purpose in Egypt, transform the light from the courtyard around which the galleries are placed. Their firm horizontal lines point the visitor forward from region to region. The floor itself seems to move. Each room, dedicated to one region, is paved with a different stone—from bright Egyptian marble, patterned with great sunbursts, stars, and cartouches in the entrance hall, all the way around to the gentle sandstone of India.

By the time that we reach the arts of the western regions—southern Spain and North Africa—we suddenly realize that we have traveled a huge distance. Some four thousand miles separate Cordova from Central Asia. In medieval conditions, this would have taken the best part of a year to cover. Reaching the end of the galleries, we are brought up sharp by a small Moorish courtyard framed by arches in stucco work, carved by contemporary craftsmen from Morocco, mounted on columns of the fifteenth century. The heart leaps at the sheer joie de vivre of it. It is a delicious condensation of the insistent beauty that has pressed in around us throughout our journey.

The layout of the galleries is devoted to stressing the diversity of the lands and cultures associated with Islam. Yet the rooms are aligned in such a way that we can shrink the distances between different regions. For example: if we look across the galleries from the room dedicated to the arts of western Islam, our eye catches, in the distance, a majestic Ottoman carpet. On this carpet, patterns that had already circulated through many regions for centuries, Andalusia and North Africa among them, are gathered up once again, in sixteenth-century Anatolia, into yet another explosion of beauty.

Our journey is constantly punctuated by such thrills of recognition across wide distances. The objects in each room do not fall into enclosed regions. Nor do they speak of a rigid uniformity. Rather, they emphasize the remarkable degree of mutual visibility created by a civilization that had turned the southern Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Iran, along with Central and South Asia, into a vast whispering gallery of stories, motifs and techniques.

But the new arrangement does something more. We are not invited merely to view this art. Like its original owners, we are invited to be engulfed in it. We see carpets and panels; lamps, vases, and eating ware; austere Korans in the challenging new Arabic script; textiles bearing motifs that reach back for centuries to the courts of the Roman emperors and to the kings of ancient Persia; tiles whose inscriptions discreetly fill the room with visual whispers of praise of God and with prayers for the good fortune of the owner, whose very inkwells (decorated with figures of the Zodiac—unchanged since the days of ancient Greece) bring down upon the house the blessing of happy stars. All these are brought together, for each period and for each region, to form a series of “virtual” rooms. They echo the visual completeness of the famous Reception Room from early-eighteenth-century Damascus that has always been the pride of the Metropolitan’s collection.

Advertisement

Furthermore, exhibition cases are placed in front of comfortable stools (of modern Egyptian manufacture) with a solid ledge on which to rest one’s elbows. These allow us to sit down and sink our eyes into miniatures whose art, at its height in early modern Iran, was marked by masterly understatement—by tiny brushstrokes that invited the viewers to take their time, and to unravel at their leisure the visual subtlety of the miniatures.

What does all this mean for our appreciation of the world that produced this art?

First, the galleries make plain that what we call “Islamic art” marks the culmination of a process and not the abrupt beginning of a new age. The spectacular successes of the Muslim armies and the novelty of the Koran tend to make us think of the creation of Islamic culture as a totally new departure. But the patient work of the archaeologist and of the historian of early Islamic art tells a very different story.

To look at the glassware, the carved wooden panels, the exquisite stucco work and the silver dishes associated with Syria, Iraq, and Iran—displayed in Gallery 451 as “The Art of the Early Caliphates (7th to 10th Centuries)”—is to look at an artistic landscape still bathed in the late afternoon sun of antiquity, whether this is the antiquity of the Eastern Roman Empire or the ever-present, proud memory of the Sasanian Empire of Iran.

It is the same with the populations of these regions. The majority of them continued to live in a late late antique world. Over much of the Middle East, Christianity took a long time to shrink into the position of a religious minority. Well into the Middle Ages, Christians in the Middle East and Zoroastrians in Iran and Central Asia were the majority, and the Muslims were a vivid but small minority.

To take one example: the Syriac-speaking populations of what are now Syria, eastern Turkey, and northern Iraq continued to act as intermediaries between the Greco-Roman culture of the Mediterranean and the new Arabic culture of Baghdad in Mesopotamia. As late as the eighth century CE, abbots of great Syriac monasteries on the Euphrates still wrote about the river Tiber in Rome and the relation of the story of Romulus and Remus to the New Year’s feast of the Roman Kalends (first day) of January. This was a feast that Christians had continued to celebrate with pagan exuberance—despite the admonitions of their bishops—well into Muslim times, in great basilicas as far apart as Antioch and Tunis. In large areas of the Middle East, no clock had struck to sound the end of late antiquity.

Indeed, far from vanishing, these Christian populations played a crucial part in passing on to the Muslims much of the culture of the Greco-Roman world. This transfer happened through innumerable dialogues between representatives of the old world and their new Arabic-speaking interlocutors.

Listening to these scraps of dialogue (many of which are preserved in as yet unpublished Syriac texts), we can catch a hint of a decisive if barely audible conversation: the long, slow parley by which many members (but by no means all) of the Christian and Zoroastrian communities of the region slowly but surely talked themselves into being Muslims, while bringing into Islam much of the richness of their own culture and worldview. Seen in this light, what matters about the civilization of Islam in its first centuries is not that it created a tabula rasa. Rather, it is the exact opposite. What is truly impressive is the poise and adaptability with which a relatively small, dominant group of Muslims rode the huge swell of an ocean whose waves came from the deep past.

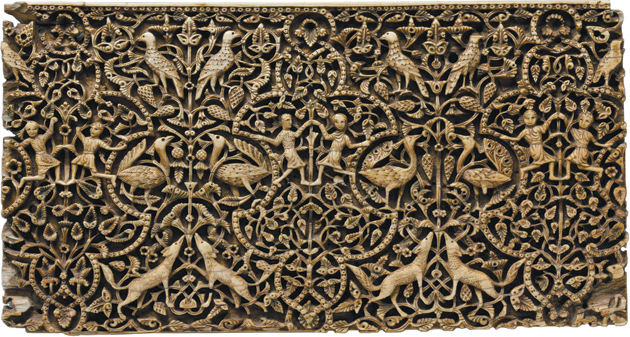

In the course of this constant, self-conscious dialogue with an older world, decisive choices were made. The portrayal of living figures in religious settings came to be widely rejected as a Christian abuse, not suitable for Muslims. Most of the figures and faces (many of them very beautiful) that we see in these galleries occur in nonreligious scenes. For a century, roughly between 740 and 840, the Middle East was shaken by a sharp debate on the use of images in worship. In Byzantium, this debate took the form of what we call the Iconoclast Controversy. Religious images survived: the walls of Byzantine churches came to be crowded with tranquil, late-classical faces. In Islam, by contrast, the tide of ornament, which was already running fast in late antiquity, reached a new height. The spread of ornament over flat surfaces created a new and distinctive form of beauty, in which one might say that weaving had replaced painting and stone carving as the master art.

Yet viewed from the West, both religious zones (Christian Byzantium and the Muslim territories) seem, despite their differences, to have much in common. Both were zones of flat art. Both opted against three-dimensional sculpture. Anyone who comes from a prolonged stay in Greece or the Middle East to the Western medieval art exhibited in the Cloisters Museum in New York is liable to be shocked, for a moment, by the heavy, seemingly bulbous statues of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints that proliferated in medieval Catholic Europe. What for us is a sign of realism and a welcome bridge toward human contact with divine and holy figures would have struck Byzantine Christians quite as much as Muslims as somehow overdone. Such art lacked the reticence and the sense of transcendence conveyed by quiet surfaces where the eye itself has to work—to give three-dimensional form to an icon of a saint or to search out, in the midst of exquisitely woven patterns, the mighty letters of citations from the Koran.

The second impression, as one walks through these rooms, is of the sheer size of the Islamic world in its final form, and of the extraordinary degree of mutual visibility that existed between its various regions. But what were the themes that passed with greatest frequency and insistency from one end of this great echo chamber to the other?

The first, of course, is the omnipresence of the Koran. Korans similar to those that occupy the center of the exhibition at the Morgan Library can be found in almost every room of the new galleries of the Metropolitan Museum. But what needs a leap of the imagination to enter into is the manner in which the omnipresence of Korans (or of citations from the Koran on objects of every kind) was based on a sense of the peculiar omnipresence of God in Muslim thought and piety.

This is a God who is always present everywhere. There is no special place reserved for God, where He might be more present than anywhere else—no body and blood of God in the Eucharist, no haunting presence of Christ and the Virgin in icons. Even the cult of saints, which was widespread among Muslims in all areas, never held the same unchallenged high ground as it did in contemporary Catholic Europe.

In the same way, no human activity was closed to God. Medieval Christians professed to be shocked by the ease with which Muslims combined piety and warfare. Nor was sex considered to be a no-go area. Celibacy was practiced by some Muslim ascetics. But it never carried the symbolic charge that it carried in Catholic Western Europe. We need to remind ourselves that Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī was a near contemporary of Saint Francis and his celibate followers. By contrast, in Rūmī’s mausoleum at Konya, in present-day Turkey, the huge sarcophagus of this spiritual giant, built in 1274, is flanked by the smaller tombs of an entire family of thoroughly well-married descendants.

What we tend to forget in making this somewhat obvious distinction between medieval Christianity and Islam is the intimacy that such an attitude toward the omnipresence of God bestows on the Koran itself. It is a book for all places and all seasons. In the words of the prayer of the calligrapher of the great Koran produced in the Persian city of Shiraz in around 1580 (which we see first as we enter the exhibition at the Morgan Library):

Oh God, make for us the Koran a constant companion in this world, a consoler to the grave, and…a guide for all good works.

The sound of the recitation of the Koran, always in its original Arabic, wove a divine thread through the noise of every day life. In a Sufi meeting place in medieval Cairo, skilled readers were employed to read out portions of the Koran from a window that overlooked the busy street, so that the holy words might be heard by passersby, and “refresh whoever hears it, or soften his heart.”

But these galleries make clear that the Koran was not the only great echo that resounded throughout this world. It requires a further leap of the imagination to recapture the weight of a parallel phenomenon: the role of luxury itself as part of a worldwide language of power. So much of what we see in these galleries is as much a product of a world of princes as is the art of the Italian Renaissance—in Florence, Venice, and papal Rome, and in the royal courts of sixteenth-century Europe. What we have to understand is the almost numinous authority that such art conveyed. It reached back to the great monarchies of the pre-Islamic Middle East, and especially to Sasanian Persia. (It is entirely apposite that one exit from these galleries leads directly to the section on the ancient Near East, where we are immediately confronted with the silver head of a Sasanian king, possibly Shapur II (310–379), one of the great kings of Persia.)

This art of the princes stretched to every corner of the Muslim territories. It eventually reached far down the social scale, in a remarkable process of democratization, so as to bring a touch of royalty to merchants, townsmen, and artisans, who dined off golden lusterware and burnished tin rather than from the gold and silver of ancient kings. It cast a penumbra far beyond the clear shadow of the Koran. This was an art of luxury that crossed all frontiers. European Christians constantly benefited from it—from the silk robes of the Christian kings of medieval northern Spain to early modern times, when the velvet sashes of Kashan, in Iran—“a high point in the history of weaving that has never been equaled since”—were prized by the Polish nobility and great Ottoman kaftans sheathed the Calvinist princes of eastern Transylvania.

For the art of princes was not marked out as a religious art. It was an art of power, comfort, and majesty. Access to it enhanced the prestige of Western Christian princes. Even the Oliphant (the famous ivory trumpet with which Roland was said to have summoned the armies of Charlemagne against the Muslims of Spain) would have come to Christian Europe as a gift from a Muslim court. Almost a millennium later, the situation was the same. A comparison of the textiles and the decorative metalwork of Europe and the Middle East, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century, such as was made available in the magnificent 2007 exhibition of the Metropolitan Museum “Venice and the Islamic World, 828–1797,” shows that the great seesaw of the princely arts—in which paintings and monumental architecture (the stuff of conventional art history) counted for less than jewelry, worked metal, and stupendous textiles—was evenly balanced between Venice, Istanbul, and Shiraz.

Let us conclude on this theme. It was brought to our attention by a genius and a genial giant in the study of Islamic art in all its periods and territories—the late Professor Oleg Grabar. The mark of Oleg Grabar is plain throughout the Met’s catalog. It is explicitly acknowledged in the article written for the catalog by Olga Bush, “Art of Spain, North Africa, and the Western Mediterranean.”

For all those interested in the art and culture of the Islamic lands, three of Oleg Grabar’s books were breakthroughs. The Formation of Islamic Art (1973) and The Alhambra (1978) revealed the stability and the purposiveness of an ideology of rule that reached back to the days of the Caesars and the ancient shahs of Iran. Seen as part of a long tradition of royal art, the Alhambra of Granada no longer appears to us (as it did to nineteenth-century European observers) as no more than a capricious pleasure palace. The message of its courtyards and exquisite decoration (which the elegance of the new Moroccan court does something to recapture) derived from a deeply rooted ideology of the ideal ruler. In the Alhambra, the king was no indolent hedonist. Rather, he was expected to recline at ease, in the manner of the ancient kings of Persia, rejoicing in a world that his own royal energy had brought to order.

In the same way, copies of Firdausi’s Shahnama—the Book of Kings of ancient Iran—appear in almost every room devoted to Iran and the lands to its east. It should not be dismissed as an elegant fairy tale. The deeds of shahs from centuries before Islam were treated as timeless paradigms for just rule. The message of the Shahnama was all the more powerful because it spoke about a dream time before the coming of Muhammad. The ideals in it stood for something wider than the wish of the believers of one religion alone. They summed up the natural, almost cosmic, yearning of humanity as a whole for order, peace, and justice. When a painter produced a copy of Firdausi’s Book of Kings for the court of the Mongol ruler of Iran—the Ilkhanid Abu Sa‘id (ruled 1317–1335)—he showed the burial of one of the primeval kings of Iran, preceded by a stallion bearing a reversed saddle in the style of a Mongol funeral. In doing this, the artist did more than add a touch of local color. He was attempting to hold a newly Islamized ruler of uncertain temper to codes of justice that were rooted in the depths of time.

In his third book, The Mediation of Ornament, based on his Mellon Lectures on the Fine Arts of 1989,2 Grabar removed what is, seemingly, the greatest barrier between ourselves and the culture of this great civilization—the overwhelming predominance of ornament in its art. Grabar showed that ornament was not trivial. It was never a mere mechanical patterning of the surface of things. Rather, he pointed out, ornament brings us back, with subliminal power, to the force of life itself. Patterns keep on keeping on. And they do it out of sheer joy: ornament “implies that decorative forms are alive, that they breathe more easily than ponderous statues and endless Madonnas.”

This was Grabar at his most challenging—even at his most characteristically mischievous. The visitor would not be advised to repeat these words aloud when passing through the collections of classical statuary or the treasures of Western medieval and Renaissance art. But they may explain something of the less easily articulated experience of pure joy that gathers momentum as we pass through the New Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Late South Asia.

This Issue

December 8, 2011

Is This George Kennan?

How We Were All Misled