1.

In 2004, anticipating the victory of the Shiite parties in the Iraqi parliamentary elections, King Abdullah of Jordan warned of a “Shiite crescent” stretching from Iran into Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon that would be dominated by Iran with its large majority of Shias and Shiite clerical leadership. The idea was picked up by the Saudi foreign minister, who described the US intervention in Iraq as a “handover of Iraq to Iran” since the US was supporting mainly Shiite groups there after overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s Sunni regime. President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt claimed that Shias residing in Arab countries were more loyal to Iran than to their own governments. In an Op-Ed published in The Washington Post in November 2006, Nawaf Obaid, national security adviser to King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, reflected on the urgent need to support Iraq’s Sunni minority, which had lost power after centuries of ruling over a Shiite majority comprising more than 65 percent of the Iraqi population.

Shiaphobia is nothing new for Saudi Arabia. The kingdom’s legitimacy derives from the Wahhabi sect of Islam, a Sunni Muslim group that attacked Shiite shrines in Iraq in the nineteenth century, and today systematically discriminates against Shias. We know from WikiLeaks that the US government regards the Saudi monarchy as a “critical financial support base” for al-Qaeda, the Taliban, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and other terrorist groups. As well as attacking American and Indian targets, all these are violently anti-Shiite. We also know that the Saudi king venomously urged his US allies to cut off the “head of the snake” by attacking Shiite Iran.

In Bahrain democratic protests by Shias, who make up around 70 percent of the population, have continued in mainly Shiite villages near the capital, Manama, despite decades of suppression by the government, recently with the aid of Saudi troops and Sunni mercenaries from Jordan, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. The Saudis, who openly sent their troops into Bahrain in March, are terrified that the unrest will spread to the oil-bearing Eastern Province where their own Shia minority resides. Human rights activists point out that Shias make up less than 20 percent of the kingdom’s workforce and less than 2 percent of its police and security forces.

Syria, just a few hundred kilometers across the desert to the west, presents an even more brutal picture. Here a civil war could be looming with defecting soldiers fighting back after protesters—many of them Sunnis who make up three quarters of the population—have been killed in the thousands by security forces dominated by a Shiite sectarian group, the Alawis, who have held power for more than four decades and are refusing to relinquish it, despite protests from neighboring Turkey and Jordan and suspension by the Arab League, of which Syria was a founding member. Earlier this year the European Union said that Iran had sent senior commanders of its Revolutionary Guards to help the Assad regime quell the unrest. In addition to recent reports of sectarian killings between Sunnis and Alawis in Homs and around the city of Hama, there are now real fears that a conflict comparable to Iraq’s is developing in Syria. Sunni minorities in Iran—in Khuzestan and Baluchistan—have also been subject to attacks, with dozens of protesters killed.

Some of those involved in the recent Arab uprisings claim that sectarian anxieties are being deliberately stoked by authoritarian regimes to maintain their grip on power. The Assad regime is widely accused of frightening Syria’s minorities—Christians, Kurds, Ismailis, Druzes—by raising the threat of a takeover by Sunni fundamentalists or takfiris—extreme Sunni groups who denounce others as “infidels.” The specter of sectarian violence can become self-fulfilling.

Many of the protesters in the Middle East deny that they have religious or sectarian agendas; they want democracy, civil rights, an end to corruption, and a change of regime. As Timur Kuran pointed out in an Op-Ed piece in The New York Times last spring, most of them do not appear to have a distinctive ideology or coherent, disciplined organizations. The exception is the highly disciplined Muslim Brotherhood (a Sunni organization), whose Freedom and Justice Party stands to do well in the coming Egyptian elections through the strength of its organization and popularity of its informal welfare programs. The Brotherhood’s top-down structure combines features of the traditional Sufi (mystical) order, based on graded levels of initiation, with modern methods such as bussing supporters to polling stations. It is a formidable contender for power in the absence of other organizations standing between the individual and the state.

The weakness of civil society organizations that characterizes many Muslim societies means that power is liable to fall by default to the military or, as in the case of Syria, to a military state controlled by a kinship group bound by tribal loyalties underpinned by a minority faith. Regimes may be crying wolf when they justify repressive measures by invoking the specter of sectarian conflict. However, the experience of Iraq—where US Administrator Paul Bremer’s foolish policy of dissolving both the army and the Baath Party after the US invasion led to a brutal conflict involving the Shiite majority and disempowered Sunnis—exposed the fragile foundations of Iraqi national identity, a feature it shares with many other Middle Eastern countries. The conflict is far from being over. More attacks on Shias by radical Sunnis can be anticipated as the US withdraws.

Advertisement

Shiism, as Hamid Dabashi explains in his challenging and brilliant new book, is a perfect foil for power but unimpressive as a modern state ideology. Its origins lie in the disputed succession to Muhammad, who died in 632 in his early sixties without unambiguously naming a successor. His closest kinsman was Ali, his younger first cousin and husband of his daughter Fatima. The Shiite minority came to believe that Ali had been designated to succeed Muhammad and that he was passed over three times for the caliphate, or leadership of Islam, before being murdered by a disillusioned supporter after a brief and contested tenure.

Ali’s younger son Husayn was killed at Karbala in 680 in an unsuccessful attempt to wrest the caliphate from the Umayyad dynasty reigning in Damascus and restore it to what he saw as the Prophet’s legitimate line. Although the Umayyads were overthrown by a Shiite-inspired revolt in 750, the victors were not direct descendants of Muhammad but of his uncle Abbas. While the majority tradition, later known as Sunni, included Ali as the fourth of the “rightly guided caliphs,” the minority Shias rejected the first three of Muhammad’s successors, whom they regularly ritually cursed in their mosques.

In effect the Shias believed that the leadership of Islam—if not its teachings—had been hijacked by usurpers. Convinced that the cause of true Islam had been betrayed by the Umayyads, and later by the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), they looked to their dispossessed leaders, the imams, or religious authorities of the House of Ali, to restore true religion and legitimate government. Unlike the Catholic–Protestant division that emerged after fifteen centuries of Western Christianity, the contested legacy of Muhammad reaches back to the time of the religion’s origins.

Max Weber famously distinguished between “exemplary” prophets such as the Buddha, who showed the path to salvation by personal example, and “ethical” prophets such as Muhammad, who demanded obedience to their teachings. Dabashi, however, challenges Weber’s view, arguing that Muhammad embraces both categories—with different consequences for the two main traditions that flow from his mission. While the vast majority of Muslims were Sunnis who “assimilated his exemplary conduct”—along with the Koranic teachings—into the textually based sharia law, the Shias “did not want to let go of their Prophet’s exemplary character and thus sought to extend his charismatic presence to their imams.” The “exemplary presence of an imam” was needed to sustain the charismatic character of the Prophet.

The crucial difference between Shias and Sunnis is not so much in the letter of the law, which Sunni legal scholars interpret in accordance with a hierarchy of sources embracing the Koran, the Prophet’s custom (sunna), consensus, and analogical reasoning. It lies rather in the quasi-mystical authority with which the Shiite legal scholars are invested.

In the Sunni tradition the ‘ulama, or legal scholars, came to act as a rabbinical class charged with the task of interpreting the Koran and the ethical teachings derived from the Prophet’s exemplary conduct as recorded in hadith reports or “traditions.” The eventual division of the mainstream Sunni tradition into four main schools of law allowed for considerable variations in interpreting these canonical texts. The mystical or “otherworldly” aspects of the Prophet’s legacy became the province of the Sufi or mystical orders that grew up around the myriads of “saints” or holy men.

The Shias, by contrast, institutionalized the Prophet’s charisma by investing their imams with special sources of esoteric knowledge to which they, through their religious leaders, had exclusive access. Hence Shiism, arguably, presents a more unified approach to Islam than Sunnism, though one that (like Protestantism) is opposed to the mainstream. During Islam’s formative era most of the holy and sinless Shiite imams in the line of Muhammad were deemed to have been martyrs or victims of the usurping Sunni caliphs. After the twelfth imam in the direct line of Muhammad finally “disappeared” in 940, Shiite authority came to be exercised by a formidable clerical establishment—comparable to the Catholic priesthood. These religious specialists were assumed to be in possession of the esoteric knowledge and interpretive skills necessary for the community’s guidance. The parallels with Christianity are striking. For the people called Ithnasharis, or Twelvers (who comprise the majority of the Shia), the disappeared or “Hidden Imam” is a messianic figure who will return (like the resurrected Jesus) to bring peace and justice to a world torn by strife.

Advertisement

Dabashi shows how this traditional belief system, enshrined in popular culture, resurfaces in contemporary literature. The scandalous death of the Imam Husayn—the Prophet’s grandson—at Karbala in 680 is reenacted annually in the popular passion plays performed in every Iranian town and village. For ordinary Shias he is the archetypical martyr for justice and truth; for Marxist writers such as Khosrow Golsorkhi (1944–1974) and Ahmad Shamlou (1925–2000), Husayn is both Christ-like victim and revolutionary icon. For Ali Shariati (1933–1975), the Islamist ideologue and leading inspiration for the 1979 Iranian revolution, he is a “cosmic figure whose murder weighs on the conscience of humanity.” In the Twelver tradition the “disappearance” of the last imam initiated a scholastic tradition “in which the sanctity of the letter of law” came, importantly, to represent “the charismatic presence of the Shi’i imams.”

The Shiite scholars do not quite constitute a church in the Christian sense, since there are no formal sacraments and they are not a corporate body endowed with powers to save Muslims from sin. Their senior leaders, the ayatollahs (“signs” of God), are not organized into a top-down hierarchy, but acquire their followings—and considerable wealth—through public recognition of their learning, reinforced by the payment to them of religious dues. Far from being a monolith they differ among themselves (like their Sunni counterparts) on matters of doctrine and practice. But unlike their Sunni counterparts (whose authority has diminished considerably since Ottoman times, with the rise of the modern state and secular education), they still dispose of formidable ability to change their societies.

Furthermore the eschatological time bomb wrapped in the myth of the Hidden Imam’s expected return packs a formidable political charge. By and large, the tradition of Twelver Shiism prevails in Iran (90 percent) and its immediate neighbors, Azerbaijan (85 percent), Iraq (65 percent), and Bahrain (75 percent), with substantial minorities in Kuwait (40 percent), Saudi Arabia (around 8 percent), Afghanistan (30 percent), and Pakistan (30 percent).

The Gulf rulers have good reason to be nervous. Shiite-inspired revolts were frequent during the early centuries of Islam, and numerous social or tribal movements were fueled by the prospect of the Hidden Imam’s expected return or justified by reference to the Prophet’s dispossessed progeny. Then came Khomeini’s triumphant arrival in Tehran in February 1979. Although he was too canny—and religiously correct—to formally claim to be the Hidden Imam himself, he allowed populist expectations surrounding the Hidden Imam’s return to work on his behalf.

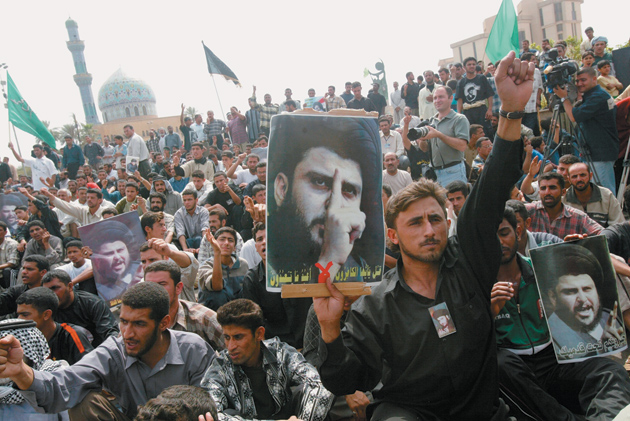

Dabashi argues that the tension between the tradition’s scholarly legalism and its revolutionary élan produces a precarious equilibrium. This is exemplified in Iraq by, on the one hand, the eighty-one-year-old Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, a scholastic jurist, and, on the other, the radical militant leader Seyyed Moqtada al-Sadr, “two Shi’is at the two opposing but complementary ends of their faith, defending their cause and sustaining the historical fate of their community in two diametrically parallel but rhetorically divergent ways.” The actual holder of power, namely the government of Nuri al- Maliki, has had to negotiate this delicate Shiite balance along with Iraq’s Sunnis, Kurds, and other minorities.

The same tension is highly visible in Iran, where President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is challenging the authority of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. In advance of the elections in 2013, Ahmadinejad is trying to boost the office of president. The struggle between the President, who has been openly accused by the liberal Green movement of buying the votes that brought him victory in the contested election of June 2009, and Khamenei (Khomeini’s successor as Supreme Leader) reflects what the sociologist Sami Zubaida has neatly described as the “contradictory duality of sovereignties”—between God and the people—“written into the constitution” of the Islamic Republic.*

Popular expectations surrounding the Hidden Imam and his return are central to this struggle. Khamenei, who represents a part of the clerical “old guard” that took power after the revolution, has gone so far as to suggest changing Iran to a parliamentary system, without an elected president—a move that former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani has stated would “be contrary to the Constitution and would weaken the people’s power of choice.” Ahmadinejad has responded by giving the debate an eschatological twist, stating that ordinary Muslims do not need the intercession of clerics to contact the Hidden Imam. For Ahmadinejad, populist expectations surrounding an imminent return (an attitude described as “deviant” by conservative clerics) serves to boost his presidential ambitions.

At the heart of this debate lies the problem of legitimacy, based, as Dabashi sees it, in a long tradition in which the revolutionary impulses born out of historical dispossession of the right to succeed Muhammad compete with compulsive anxieties about proper social behavior:

The more volatile, unstable, and impulsive the charismatic outbursts of revolutionary movements in Shi’ism have been throughout its medieval and modern history, because of its traumatic origin, the more precise the exactitude of the Shi’i law has sought to regulate, to the minutest details, the affairs of Shi’i believers—from their rituals of bodily purity to the dramaturgical particulars of their communal gatherings, to their political suspicions of anyone’s claim to legitimate authority.

Rituals of bodily purity serve to reinforce communal identities. As the anthropologist Mary Douglas famously observed in her classic work Purity and Danger, rules about pollution of the body are substitutes for morality: “They do not depend on a nice balancing of rights or duties. The only material question is whether a forbidden contact has taken place or not.”

At the same time, as Dabashi suggests, the notion of having been wronged by the existing powers, which lies at the heart of Shiism, contributes to the notion that

the veracity of the faith remains legitimate only so far as it is combative and speaks truth to power, and (conversely) almost instantly loses that legitimacy when it actually comes to power.

A logical resolution to this paradox would be a formal separation of powers between religion and state, where the religious leadership “speaks truth to power” without exercising executive authority. Such was the position of the clerical class during the regime of the Pahlavi shahs and for the most part under their predecessors of the Qajar dynasty (1785–1925), when there existed what Said Amir Arjomand has called an “unspoken concordat” between the state and the clerical establishment, with the latter refraining from criticizing the dynasty’s policies.

It was Khomeini who radically upset this de facto concordat with his doctrine of Vilayet e-Faqih—the Guardianship of the Jurisconsult—whereby the Supreme Leader and the Guardian Council appointed by him approve parliamentary candidates and have veto power over legislation (as well as control over much of the bureaucracy and armed forces) in competition with the elected president. The contradiction at the heart of the Islamic Republic exemplifies Zubaida’s “contradictory duality of sovereignties” and constitutes a major obstacle to reform. It was the Guardian Council, for example, that effectively defeated the reformist agenda of President Sayyid Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005) by rejecting his proposals—overwhelmingly approved by the parliament—for constitutional changes that would reduce the council’s power and boost those of the presidency. Constitutionally speaking, Khatami’s struggle was similar to Ahmadinejad’s, although his social outlook (as a moderate with liberal instincts and advocate for international dialogue) was the diametrical opposite of Ahmadinejad’s.

This constitutional impasse, in my view, is a direct reflection of Dabashi’s paradox of legitimacy, and its consequences have been dire:

What I believe is happening in Iran today begins with the simple fact that…the ruling Shi’ism has lost its moral legitimacy. It has lost it by simply being in power and trying in vain to remain in power by maiming and murdering its own people.

2.

If Dabashi had restricted himself to a political and theological analysis his thesis would be interesting enough, but his ambitions are much wider. As he explains in his preface, part of his book charts a “major epistemic shift” in Shiism from doctrinal issues arising out of historical events to artistic manifestations of the faith, including in literature and architecture. A question that arises is how such a comprehensive vision of the faith can retain its distinctive Shiite labeling—since many of the features he delineates could be described, more broadly, as “Islamic,” or more specifically as distinctly Persian or Iranian. He writes eloquently about four of the masters of Persian literature—among them the great mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207–1273), founder of the Mehlevi order of dervishes, and the poet Sa’di (1184–1291). He sees these Persian writers as the forerunners of a literary tradition that culminates in the lyrics of the great Hafez (circa 1320–1389), who gave

anyone who was fortunate enough to be born after him an expansive universe, much as Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven mapped out the topography of the emotive cosmos of European philosophers and mystics.

These major figures, he acknowledges, transcend sectarian affiliations, just as the great composers he cites reach out beyond the Lutheran or Catholic traditions in which they were raised. “When we remember them we scarce know or care if they are Sunni or Shi’i, nor does it matter.”

In line with this approach he argues that Shiism is not so much a sect or minority tradition of Islam, but a comprehensive and variegated version of the entire faith. It is “the dream/nightmare of Islam itself as it goes about the world…a promise made yet undelivered to itself and to the world.” It is “the hidden soul of Islam, its sigh of relief from its own grievances against a world ill at ease with what it is.”

However, this vision of Shiism as a moral force or conscience embedded in Islam at its roots appears to contradict his historical account of Safavid Persia, which he sees as the apotheosis of Islamic civilization, when variegated elements of Shiism merged triumphantly in the “paradoxical panning out of what was now a state majority religion with an enduring minority complex.”

The Safavids, who ruled Persia and the adjoining lands between 1501 and the 1730s, made Shiism the state religion. According to Dabashi they succeeded in integrating the mystical and practical dimensions of Islam on Shiite foundations while maintaining a philosophical approach consonant with the idea of God as the cosmic intellect or ultimate consciousness. Dabashi sees the architectural splendor of Isfahan, the Safavid capital, as the material expression of an intellectual spirit comparable to that achieved by Western Christendom on the eve of the Enlightenment. For him the magnificent piazza known as the Meydan-e Naqsh-e Jahan (Image of the World Square) corresponds to Immanuel Kant’s vision of a vast and vital public space. It opened the way for “reason to become public, for intellect to leave the royal courts and the sanctity of mosques alike and to enter and face the urban polity of a whole new conception of a people.”

Tragically, in Dabashi’s view, the Safavid vision of the public space as a forum for reasoned discourse succumbed to the “hungry wolves” of Afghan invaders, imperial rivalries between Russians and Ottomans, and the colonial machinations of the French and British. Internal forces of dissolution also played their part, with raw tribalism replacing the vigorous cosmopolitan public culture the Safavids had striven to create. By the end of the eighteenth century Shiite Iran had returned to forms of tribal governance, along with a restored religious scholasticism.

The triumph of nomadic tribalism under the Qajar dynasty that endured from 1785 until 1925 “necessitated a clerical class of turbaned jurists and their feudal scholasticism to shore up its precarious legitimacy.” This historic regression, according to Dabashi, was exacerbated by the doctrinal victory of the Usuli school of jurists (who use independent reasoning in their judgments) over the Akhbaris, who were more bound by precedent.

On the face of it, Dabashi’s view appears counterintuitive, since the use of independent reasoning would seem to allow more room for individual initiative and public reason. But when we take account of the renewed tribalism harking back to the pre-Safavid era, the victory of the Usuli jurists served to enhance clerical authority at the expense of the public and cosmopolitan aspects of Shiism that had been encouraged by the Safavid state. In effect the clerical establishment made a deal with the nomadic rulers, using its authority to bolster their claims to power in exchange for clerical privileges. Members of an inward-looking, xenophobic clerical establishment, obsessed with issues of purity and pollution, became the guardians of tradition and bearers of popular identity, a process enhanced by defensive responses to Russian and Ottoman territorial encroachments and later to the pressures arising from growing European power.

Dabashi is fascinated not just by the intellectual and political ramifications of this process—the rise of Khomeini, the fall of the Shah, and the establishment of the Islamic Republic—but also by what might be called its manifestations in the Shiite psyche. In exploring this landscape he acknowledges the influence of his teacher and mentor Philip Rieff (1922–2006), author of The Triumph of the Therapeutic and a major interpreter of Freud.

According to Rieff the neurotic symptoms Freud identified in his patients were a reflection of the decline of traditional moralities: as the anchors of religion were loosened, instinctive desires became less easy to control. Freud’s solution was to provide his patients with a technique that would enable them to manage their instinctual lives in a prudent and rational manner. The flaw in Freud’s atheistic approach—according to Rieff—lay in his failure to recognize that the underpinning of the repressive myths that inform human action lie in a supra-empirical or transcendental source of authority, namely the sacred.

In Rieff’s view, authority rooted in the sacred infuses our creativity with the guilt without which we cannot manage our instinctive impulses. Desire and limitation, eros and authority, are intimately connected. The tension between them provides the energy for all artistic endeavors. Yet if we deconstruct them by unmasking, as it were, the secret police, as therapists would have us do, our culture will lose its vigor. “A culture without repression, if it could exist,” Rieff wrote in a passage cited by Dabashi, “would kill itself in closing the distance between any desire and its object. Everything thought or felt would be done, on the instant…. In a word, culture is repressive.”

Dabashi’s perspective on the relationship between culture and repression does not mean that he subscribes to the current brutal repression in Iran, where activists, artists, and journalists are being persecuted, and in some cases executed, for opposition activities, or that he endorses the subjection of art to religious bigotry. Dabashi is a firm supporter of the reformist Green Movement. In March he chaired a special meeting in New York of the Asia Society to honor the Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, who has been sentenced to six years prison with a twenty-year ban on his work. The discussion, however, evoked some significant Rieffian themes, showing, for example, how the rules forbidding male–female interactions on screen can be used by ingenious directors such as Panahi to expose the contradictions of Iranian society in ways unintended by the censors.

Adopting an approach that builds on Rieff’s ideas, Dabashi proceeds to analyze two works by well-known Iranian artists. In Close-Up (1990) Abbas Kiarostami created a film about an actual person—Hossein Sabzian—who in real life impersonated the celebrated activist turned filmmaker, Mohsen Makhmalbaf. In making his film Kiarostami has Sabzian reenact this impersonation in front of his camera. The film, according to Dabashi, is driven by “the aesthetics of formalized representation”: Kiarostami plays with the irony or double-mirror effect of having a real person playing himself in a fictional recreation of an actual event.

Any possible political implications are left unexplored. Dabashi sees Kiarostami’s film as exemplifying the deep cultural split within Shiism between art and politics, with art disengaged from politics, and politics assuming

an increasingly one-sided ideological disposition, banking almost exclusively on the feudal scholasticism at its roots at the heavily expensive cost of denying, rejecting, or destroying its non-juridical heritage—from philosophical and mystical to literary, poetic, performative, and visual.

In contrast to Close-Up, Dabashi finds a redemptive grace and “singular act of visual piety” in Tuba (2002), a video installation by the artist Shirin Neshat. In this video the face of a woman fades onto a perfectly matched landscape of rocky hills. Pilgrims stop at the threshold of a sacred space before transgressing, or desecrating, its boundaries. Dabashi’s lengthy description traces the archaeology of Neshat’s installation, from its ambiguous origin in a Koranic phrase, by way of its elaboration in early commentaries, to a gnostic invocation of a female deity and vanishing paradise in the novel Tuba and the Meaning of Night (1988) by Shahrnoush Parsipour. His commentary suggests that the psychic split afflicting Shiism, between the scholasticism of the ayatollahs and the aesthetic formalism he laments, may only be temporary. He writes that while a culture may fancy itself “secular,” “its sacred memories are nevertheless busy thinking its ideas and populating its dreams.”

An American-Iranian well known for his hostility to Israel and America’s Middle East policies, Dabashi makes no concessions. He attacks Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, author of the popular The Shia Revival, for being a “native informer” who reduces the “multifaceted, polyvocal, worldly, transnational, and cosmopolitan” culture of Shiism to a “one-sided, divisive, sectarian, and factional” system, a perspective that serves to “facilitate the US military domination of a strategic area,” while confirming the Shiite religious class in their “belligerent clericalism.” In the case of Noah Feldman, legal adviser to Paul Bremer, whom he accuses of writing sectarianism into the Iraqi constitution, his criticism seems misplaced, particularly in view of the nuanced lengths to which Feldman has gone in arguing against “imposed constitutionalism.”

A larger criticism of the book is that Dabashi fails to address Shiism as comprehensively as his project demands. For example, while he celebrates the Ismaili variant of Shiism in the work of Nasir Khusraw, he is silent on the survival of this tradition for nearly a millennium in the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia (now Tajikistan), followed by seven decades of Communist rule. He is also silent on the remarkable spread of Ismailism in South Asia (mainly Sindh, Gujarat, and Mumbai).

With its unique language and literature, for which the Khoja Ismailis of India invented a special language and script, and its genius for translating Hindu concepts and symbols into the Islamic religious vernacular, Ismailism may be seen as a significant inheritor of the Safavid version of Shiism that Dabashi admires. An impressive model of an enlightenment tendency within the Islamic fold, Ismailis are engaging creatively with contemporary architectural practice, commerce, public health, women’s rights, social empowerment, and a range of contemporary concerns, not just in the developing world but in Europe and North America.

I suspect that Dabashi neglects this quiet Islamic revolution because it does not fit his theme of a tragic bifurcation between artistic creativity and juridical scholasticism that afflicted Iranian Shiism in the post-Safavid era. As a Shiite minority living in the diaspora but with a strong centralized leadership, the Ismailis have preserved the integrity of their tradition while advancing public engagement with the countries in which they reside. They have achieved this by running with the flow of political power—with the British in India, East Africa, and Canada, with the Portuguese in southern Africa, with the Soviets in Central Asia, and—until the current crisis—with their former Alawi rivals in Syria. Dabashi’s somewhat cliché-ridden, anti-imperialist model is based essentially on the Iranian historical experience. It would have to be modified considerably if he were able to accommodate the Ismaili story of social and educational advance, business success, and significant cultural achievements.

On balance, however, his swipes at academic colleagues, unfair or ill-judged as they sometimes appear, are the obverse of a generous vision, not just of Shiism but of Islam very broadly conceived. In pursuit of this vision he combines his meditations on Islamic culture with an impressive grasp of Western thinkers (including Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx, Weber, and Habermas) and above all of Freud, as refracted through the important but neglected prism of Philip Rieff.

Dabashi’s extraordinarily rich and powerful book takes Shiism out of the sectarian ghettos where it was largely confined when it became an ideological weapon of the Persian Empire in its rivalry with the Sunni Ottomans. By emancipating Shiism from its instrumental use by the Islamic Republic of Iran, he has performed a vital cultural—and political—service.

-

*

Sami Zubaida, Islam, The People and the State: Political Ideas and Movements in the Middle East (Routledge, 1989). The same points are made in Zubaida’s article “Is Iran an Islamic State?,” in Political Islam: Essays from Middle East Report, edited by Joe Stork and Joel Beinin (University of California Press, 1996). ↩