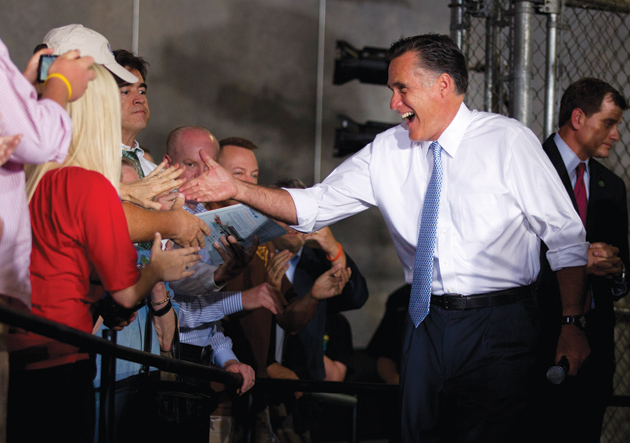

Little suspense attaches to the outcome of the 2012 presidential race in Texas, which is all but certain to give its thirty-eight electoral votes—up from thirty-four in the last election—to Mitt Romney. Let’s just say certain. This is surprising because Mitt Romney was not designed by the God that made him to do well in Texas. Mitt Romney is a Mormon, which would not make him the first choice of Texas Baptists, some of whom doubt that he can be properly identified as a Christian. Mitt Romney was the governor of Massachusetts, which many Texans—let’s say most Texans—hold in suspicion as the most liberal state in the country. Mitt Romney as governor passed a state health care law that provided the template for Barack Obama’s much-disliked—let’s say hated—Affordable Care Act. Over the last nine months, Mitt Romney outspent, outpolled, and outlasted a platoon of other candidates for the Republican presidential nomination whom most Texans would have preferred, given the choice, conspicuously including Texas Governor Rick Perry.

But Mitt Romney is the last man standing with a plausible hope of beating Barack Obama, who seems to incorporate in his person, or represent in his beliefs, just about everything that the Texans who run Texas have detested and feared and hoped to crush over the last 150 years. Of all the many Republicans who have sought the nomination, Romney without question speaks best of the man most Texans hope to defeat. He says Obama is a nice guy who is in over his head; he says Obama wants what’s best for the country but doesn’t understand business and can’t get the economy going again.

Romney can tick off the failings of the president like any other Republican but he precedes each one with a friendly word or tip of the hat. It drives conservatives crazy, not only but also in Texas, where the preferred oratorical style is closer in tone to the Book of Revelations. In a verbal scuffle over cutting health care costs a few years back, Texas state legislator Debbie Riddle went for the jugular of entitlement in the preferred style: “Where did this idea come from that everybody deserves free education, free medical care, free whatever? It comes from Moscow, from Russia. It comes straight out of the pit of hell.”

Romney might cut the last penny from the last program to provide aspirin for undocumented single mothers but he would never say anything like that. In Texas, but not only in Texas, this makes him a…moderate. The word says everything and must stand alone. For Tea Party conservatives it is the ultimate argument stopper. “Liberal” is no longer the word that brands an untouchable. To call a political candidate a moderate in Texas is to class him or her with welfare cheats and dead armadillos. During the recent Texas state primary for the Republican Senate nomination, television ads for Ted Cruz—a former state solicitor general—hammered on the theme. The word “moderate” was stamped wanted-poster style across a mug shot of Cruz’s opponent, Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, who is backed by Rick Perry.

Like Dewhurst, Romney rejects the scurrilous charge and insists he’s no moderate but a true conservative. What truly conservative Texans feel about Barack Obama is implied by the lengths to which they will go to deny him a second term—almost unimaginable lengths, requiring sacrifice of principle so deep, so complete that they will vote (shudder) for a moderate Mormon from Massachusetts.

The underground rivers of anger boiling beneath the American political landscape in this presidential year, spewing superheated spittle and fumes of sulfur wherever they pierce the surface, may be seen as posing with new intensity the great unanswered question of American history: What lies at the core of the divisions of the American people? Battalions of scholars are ready to cite chapter and verse in explanation of the big divisions—the poor against the rich, the country against the city, the nativists against the latecomers, the whites against the people of color, those who hold money close against those willing to spread it around, the believers in the inerrancy of the Bible against the secularist accepters of science, those who wish to hear nothing about sex against those willing to discuss everything, those who would wield the rod against those who would spare the rod, those who wish to control women against those ready to let women decide. These are the nine fissures that split the American national psyche. All center on questions of control.

To understand why Americans so often approach a political season as if it promised Armageddon, some general questions need to be addressed, but usually aren’t. The first is the fact that there are so many divisions, and they are all somehow mysteriously related. The second is the fact that those who occupy the conservative, traditionalist, red-state side of each division have organized themselves politically with increasing success since 1960, let us say, when the United States elected its first Catholic president. The third is the fact that the anger driving their efforts appears to be approaching the kind of elevated temperature that can spontaneously ignite the atmosphere.

Advertisement

Everybody who writes about American politics at some point writes about this. Some observers concede that the noise level is rising, but think it’s still only politics as usual. Others say hold on, pay attention, there’s something different going on here. At the outset of As Texas Goes…, her new book about the forces that drive American politics, the New York Times columnist Gail Collins seems decidedly amused, but not quite 100 percent sure it’s okay to remain calm.

It was Rick Perry who caught her attention three years ago when he showed up angry at a Tea Party rally in Austin, the Texas state capital, refusing to put up with one more minute of oppression from Washington and all but threatening to lead Texas right out of the union. “Texas has yet to learn submission to any oppression,” Perry said, quoting the George Washington of Texas, Sam Houston, “come from what source it may.”

“We non-Texans were somewhat taken aback,” Collins writes. “How long had this been going on? Was it something we said?”

Perry’s truculence set her to thinking and what struck her most over the next couple of years, and is now reported in her wide-ranging, often funny, and always sensible book, was the sheer oddness of the Texas conviction that it was being manipulated, ignored, meddled with, insulted, oppressed, and taxed to death by faraway Washington. Maybe once, not now, in Collins’s view. The intrusive, know-it-all, pointy-headed intellectuals from Harvard of legend all departed the American scene decades ago with Alabama Governor George Wallace. Now the influence is all running in the opposite direction.

Collins builds a list. It was Texas back in the 1980s that set the nation on the road to deregulating American banking, just as it was Texas that defended the sacred right of oil producers to pay taxes at a derisory level, Texas that laughed at “global warming,” and a Texan in the White House who told the scientists to button their lips; Texas that wrung social strife out of textbooks not just for Texas, but for everybody; Texas that got the whole country to threaten schools and teachers with the garrote if kids didn’t get ever-higher grades on standardized tests, Texas that led the nation in executions, Texas Senator Phil Gramm who (with help) pushed through the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which cracked the door for packaging and selling subprime loans, Texas presidents who banged the drum for foreign wars, Texas that hired private firms to do public business, and Texas that fought abortion, defended the right of citizens to go about armed, argued for rock-bottom social services (if any), and, yes, stood up in public to argue yet again that “evolution is hooey.”

Collins has done her homework. Her book is short (only 195 pages of text) but solid, based on wide reading and several score interviews. Her purpose is straightforward—to sort through the torrent of angry rhetoric, identify the separate claims about the world according to Texas, examine each in sober detail, and offer a brief for rebuttal. Collins has an eye for the loony in Texas life and politics but readers should not expect the sort of thing the late Molly Ivins used to say, nor anything like the language in which she used to say it. Ivins worked for a lot of magazines and newspapers, including The New York Times for four tense years, but Texas is where she started (at the Houston Chronicle) and ended (Fort Worth Star-Telegram). Six years at the Texas Observer in the 1970s fixed her style and point of view. There, she wrote later,

when I would denounce some sorry sumbitch in the Lege [the legislature] as an egg-suckin’ child-molester who ran on all fours and had the brains of an adolescent pissant, I would courageously prepare myself to be horse-whipped at the least. All that ever happened was, I’d see the sumbitch in the capitol the next day, he’d beam, spread his arms, and say, “Baby! Yew put mah name in yore paper!”

It was that sort of field observation that made it impossible for Ivins to go on writing for the Times, where Collins has worked since 1995. She makes no secret of where she stands, and her eye can be sharp enough to hurt, but her sense of humor does not venture much beyond irony. Ivins on Texas is unalloyed delight. Collins is relentless and convincing. Some of her strongest material concerns the history of school reform in Texas (counterintuitive on its face, she writes), beginning in the 1980s with a blue-ribbon panel headed by a Texas zillionaire in the classic mold, H. Ross Perot, who made a ton of money processing Medicare data for the federal government, and then set out to remake the world.

Advertisement

His first effort came up with a solid indictment of the dismal state of Texas secondary education, which limped near or at the bottom of the list of things schools are supposed to do, beginning with graduate kids from high school. In 1993 the Texas Supreme Court ordered the state to find a new, more equitable system for funding public schools, and after several attempts the state passed a bill that provided more money (the thing Texas hates to do most) and mandated some kind of system for testing what children in the remade schools were actually hoisting aboard. This was named the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills. It was basically a test, and if the kids failed, the school failed, and if it failed badly enough for long enough, teachers would be fired and schools might even be closed down altogether.

The new state education program came at a propitious moment in the career of Texas Governor George Bush, when early assessments got people talking about the “Texas Miracle.” Bush took the good news to the White House in 2001 and turned it into No Child Left Behind, with a decided emphasis on… Here Collins reminds the reader that the program in its original form stressed two tools—more money and more testing. “Bush fixated on one of them,” Collins writes. “We will pause here while everyone guesses which.”

That was a decade ago. Things didn’t exactly work out. First off, all those concerned parents meddling with Texas textbooks only succeeded in making “evolution—and history, and everything else—really, really boring.” Bored kids did not do well on standardized tests. Since test results were important, teachers taught the test. Free-ranging inquiry was out, drill was in. Soon even the Texas Miracle was unveiled as a fraud. Kids of yesteryear used to sneak into teachers’ offices to change a D to a C or a B. Now Texas school administrators were nudging test results upward for entire schools and districts, or skewing the numbers in other ways—like classifying as transfers kids who had dropped out.

The extra money Bush had approved as governor slipped away under his successor, Rick Perry. Class sizes crept back up. Special programs were dropped. Even former First Lady Barbara Bush was appalled by the train wreck, lamenting in the Houston Chronicle a year ago that pay for teachers in Texas ranked thirty-third in the nation, and the state was thirty-sixth in high school graduation rates, forty-seventh in literacy, and forty-ninth in the verbal section of the national Scholastic Aptitude Test.

How should proud Texas deal with this dangerous failure? Bush struggled for an answer within the limits of acceptable political discourse in Texas. She called on parents, churches, and business groups to all pitch in, but the word “tax” did not appear in her piece. The word “money” did not appear. The implication of Bush’s argument is obvious: if you want better schools in Texas, you have to pay for them. But no member of the Texas Republican political establishment dares say anything of the sort. All Bush managed was the faint query, “Can we really afford to cut state funding for our students?”

Collins of course says plainly what Bush will not, and attacks an array of Texas core issues in similar fashion. Under the glossy claims is a relentless history of policy failure, often marked by the transfer of an ocean of public money into private hands. There’s not a lot of blood in Collins’s method; she performs her executions cleanly, with facts, irony, and the testimony of beleaguered Texas liberals who explain what it means to operate a state government on the principles of “low tax, low service.”

Start with the low taxes. In the first place there is no income tax, and an amendment to the state constitution requires a statewide referendum before an income tax can be imposed. In place of an income tax there is a state sales tax, which of course lands most heavily on the poor. The bottom fifth of Texas residents pay about 12 percent of their income in sales and other taxes, the top fifth about 3.3 percent. But overall, taxes are low, just as Texas claims, which means that the state is starved of public funds, with the result that it does not offer much service of any kind to anyone, rich or poor.

To be young, employed, well-paid, and in good health in Texas with no kids in public schools and no aged parents or disabled children to look after is a gentle fate; the opposite, not so gentle. To get the full picture of what isn’t provided requires a list and for the last decade the legislative Study Group, which supports the beleaguered liberals in the legislature, has created and annually updated a list of just which services are in scant supply, and just how low they go. It is called “Texas on the Brink” and Collins prints the whole of it as an appendix to her book.

Odds are good that Barbara Bush took her Texas school rankings from this list. From it you will learn that in tax revenue raised per person in the United States Texas ranks forty-sixth, but first in executions, and last in state spending per person for mental health. It is also last in the percentage of people over twenty-five with a high school diploma, last in the percentage of “non-elderly” women who have health insurance, last in the percentage of women getting prenatal care in the first trimester, and last in employees covered by workmen’s compensation. It is first in the gross amount of carbon dioxide emissions, first in the amount of toxic chemicals released into the water, and first in the percentage of people without health insurance. Not listed among the scores of categories is where the state of Texas ranks in what might be called official commitment to “quality of life.” That commitment is not something you can measure or count, really. You have to listen for it.

For a start, you might listen to Ted Cruz, the candidate for the Republican nomination to replace Kay Bailey Hutchison in the US Senate. I’m not sure Cruz would grasp what you meant by official commitment to quality of life. It is certainly not something that he would bring up on his own. Cruz won just enough of the vote in the May 29 primary—34 percent plus a sliver—to deny the nomination to Rick Perry’s choice, David Dewhurst. A runoff will be held on July 31. What this primary fight is about is difficult to pin down. Cruz is not a policy wonk. To explain what is driving him, Cruz prepared a three-minute talk, face-on to the camera, looking silkily earnest, and speaking with the slow, penetrating voice that, one imagines, Cruz imagines was the voice used by Texas hero William Travis in 1836 when he invited the Texas patriots to step across a line drawn in the sand to join him in fighting to the death at the Alamo. Cruz doesn’t mention the Alamo heroes, but his background music does. Cruz’s ad is readily found on YouTube.

In these remarks Cruz has nothing to say about questions of government policy, programs, or operations—the things government does. His message is built around such words as “stand and fight,” “constitution,” and “liberty.”

“We are facing the epic battle of our generation,” Cruz says at the outset. He urges voters to ask of their leaders what they have done?—a word he pronounces in italics. What Cruz has done, during his five years (2003–2008) as the state’s solicitor general, was to go to Washington to appear before the Supreme Court to defend the Texas Ten Commandments Monument, the Pledge of Allegiance, the Second Amendment, and US sovereignty from the World Court.

His talk ends on an apocalyptic note. “There’s never been a time in our nation’s history when there was a greater need to fight to defend freedom.” Think about that “never.” Defend our freedoms from what is not specified, but the locus of danger is obviously in Washington, where Cruz anticipates perpetual battle. “If you want a senator who will compromise with the Democrats,” he said on Fox News recently, “then David Dewhurst is your choice.”

Dewhurst, recall, is the moderate.

But Ted Cruz had not yet appeared on the horizon when Gail Collins was writing As Texas Goes… She was after bigger quarry, Rick Perry, who had been warming up for a run at the White House over the previous several years. Last August, he held a giant prayer meeting in Houston on the eve of declaring his candidacy. The atmosphere of the seven-hour prayer session was not quite that of an old-time tent revival meeting, but close.

“Father, our heart breaks for America,” Perry prayed with eyes closed and hands clasped in front of a crowd of thirty thousand. “We see discord at home. We see fear in the marketplace. We see anger in the halls of government and, as a nation, we have forgotten who made us, who protects us, who blesses us, and for that, we cry out for your forgiveness….

“You call us to repent, Lord, and this day is our response.”

One longed for the late Molly Ivins. “The next time I tell you someone from Texas should not be President of the United States,” she said after the second George Bush mounted the national stage, “please pay attention.” Rick Perry was designed by the God who made him for a royal skewering by Molly Ivins, but God was merciful, and spared him that.

Yet Gail Collins in her thorough and serious way has pretty well taken Perry apart. Her book would have been at the right hand of every Democratic strategist trying to fend off a national Perry campaign, if he were still in the race. For ten minutes last August it seemed he might go the distance. His formal announcement came a few days after the day of prayer, and he soared briefly in the polls. Then things started to go wrong. Collins remarks that Perry “went on to become one of the worst candidates for president in all of American history.” He performed poorly in early debates, did worse in later ones, won no friends when he denounced homosexuality as “deeply objectionable,” worried even Christian backers when he attacked Obama’s “war on religion,” alarmed just about everybody when he said on stage while the other candidates listened in various postures of amazement that he would eliminate three cabinet-level departments when he got to the White House, but could remember the names of only two of them. It did not help a few minutes later when the name came to him—the Department of Energy! Next day a British newspaper said Perry’s campaign was in “meltdown” following “one of the most humiliating debate performances in recent US political history.”

Perry’s five-month ordeal was painful to watch. The problem was Perry himself. He was like a singer who had lost his voice. Few voters could imagine him with confidence as president. In January he finished fifth in the Iowa caucuses, then gasped and twitched with indecision for two weeks like a fish dying on the bank of a stream, and finally suspended his campaign, throwing his support to Newt Gingrich, whose White House hopes were in fact equally dim.

It’s amazing what a period of quiet reflection can do. Perry has made his peace with Mitt Romney, and is behind him a thousand percent. “God help us if he doesn’t win,” Perry told Fox News at the beginning of May. That’s something, isn’t it?

Perry’s failure as a candidate despite rhetorical command of all the elements of the anger that fuels the Tea Party might be seen—could conceivably be interpreted as marking—the high- water mark of the red tide that poisons the waters of American politics. Those deep fissures over questions of control in the American psyche—aren’t we moving beyond those now? Perry could not make the anger play and Mitt Romney, while insisting that he shares every Tea Party grievance (pretty much), deliberately dials down the temperature of his own language on the stump. He sounds more like a cheerful, reasonable man. He is willing to call Barack Obama a good guy. If Texans are willing to vote for a relatively moderate Mormon from Massachusetts, does that mean they are cooling off? Does it mean we can start talking policy again, reach across the aisle, see the other fellow’s point of view, get over it?