1.

Although there are countless tangents that a career in the building arts can take, it is nonetheless most unusual for a major architectural practice to emerge once a firm’s principals are well into what is loosely called middle age. Before the professionalization of architecture in the nineteenth century, it was standard for an aspiring mason or carpenter to begin his apprenticeship at fourteen and to become a master builder by his early twenties. But with today’s protracted educational adolescence and a much longer life expectancy, architects now finish schooling in their mid- to late twenties, work for an established firm during their thirties, and then, if sufficiently talented, embark on independent practice at around forty.

Designing a house for one’s parents is an almost cliché rite of passage—Le Corbusier and Robert Venturi are prime twentieth-century examples of helpful familial patronage—followed by more residential commissions and nondomestic renovations or additions. Only after two decades of sustained experience do big commissions generally start to arrive, although by the age of fifty typecasting also sets in.

If one is fortunate enough to bring off several well-received projects, a Pritzker Prize might come during one’s sixties, depending on that coveted award’s shifting and often inscrutable notions of artistic excellence and geopolitical distribution. Winning the Pritzker assures a flood of work in one’s seventies and eighties, jobs necessarily carried out by assistants as the demands of modern-day cultural stardom and the inevitable waning of physical capacities prevent many architects from attaining the transcendent final phase more easily achieved by artists in other mediums. Architecture is not a profession for the faint-hearted, the weak-willed, or the short-lived.

Thus among the most extraordinary emergences in the building arts during recent decades has been the husband-and-wife team of Ricardo Scofidio, now seventy-seven, and Elizabeth Diller, fifty-eight, who first attracted attention beyond avant-garde architectural circles in 1999 when they were awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant. Together with the forty-eight-year-old Charles Renfro they comprise the New York firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Scofidio and Diller (who founded their office in 1979 and made Renfro a full partner in 2004) had long appeared determined to be among the theoreticians and educators who infuse architectural thought with vivid imagination but construct little if anything at all. In that regard they followed the lead of their Cooper Union colleague John Hejduk (1929–2000), the school’s longtime dean, a poète maudit who fantasized in drawings and philosophized in print but built almost nothing.

The prevailing impression of this maverick couple as consummate architectural luftmenschen was heightened by the Whitney Museum of American Art’s enigmatic 2003 exhibition, “The Aberrant Architectures of Diller + Scofidio.” Devoid of almost anything the lay public could comprehend as architecture or urbanism, the show presented a series of the subjects’ more-or-less whimsical installation pieces. These displays included “Tourisms: suitCase Studies” (1991), a gallery with fifty identical open Samsonite valises suspended from the ceiling, each documenting a historic site in one of the United States but limited to famous beds and battlefields. Another space contained “Mural” (2003), a sixteen-foot-high robotic power drill that moved along 330 feet of wall-mounted track and randomly bored holes in a partition between two galleries. It was all great fun, but the designers’ hermetic cleverness left many visitors baffled.

The first structure that Diller and Scofidio executed—their Blur Building of 2000–2001 in Switzerland—might be seen as a witty riposte to those who wondered if the pair would ever actually erect one of their schemes. Commissioned by the Swiss national exhibition Expo.02, this aqueous caprice (subject of Diller + Scofidio: Blurred Theater, a new monograph by the Italian architect and writer Antonello Marotta) was created atop an ovoid open-air platform in Lake Neuchâtel at Yverdon-les-Bains.

Connected to the shore by a pair of long gangways, the Blur Building was created by a sophisticated system of 31,500 high-precision high-pressure water jets. This mysteriously cloudlike water vapor “pavilion,” which measured more than three hundred feet wide, nearly two hundred feet deep, and sixty-six feet high, could contain as many as four hundred visitors, who were given waterproof ponchos to wear within the wrap-around canopy of fine mist expelled from the lightweight metal framework. In its shifting contours and indeterminate outlines, this phantom structure obliquely commented on what the architect Greg Lynn in 1996 termed “blob architecture”—free-form constructs enabled by new computer-aided technologies (the most famous being Frank Gehry’s biomorphic Guggenheim Museum Bilbao of 1991–1997 in Spain).

Diller and Scofidio’s beguiling jeu d’esprit became the hands-down hit of the Swiss fair. The idea of fashioning an inhabitable space from water—a tantalizing contradiction in architectural terms—has fascinated visionaries for centuries, especially writers in Islamic Spain who during the Middle Ages fantasized about fountains with liquid domes that one could enter. That evanescent dream was finally brought to dazzling life in this triumph of the architectural imagination.

Advertisement

2.

In the decade since the frisson of the Blur Building, Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro have executed several exemplary public spaces that provided pragmatic, cost-efficient solutions to underutilized or ineffective urban settings. The most justly celebrated of these commissions has been Manhattan’s High Line, begun in 2004, with two of its three sections now completed. This collaborative effort is headed by James Corner Field Operations (a firm specializing in converting urban infrastructure) with the crucial participation of Piet Oudolf, the Dutch landscape architect known for his naturalistic plantings of environmentally appropriate indigenous species.* The Corner office largely focused on shoring up the decaying freight rail trestle to make it safe for heavy pedestrian traffic, whereas Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro addressed broader questions of how this new kind of park might best be used and enjoyed.

Well versed in such theoretical concerns as “the gaze”—the ways in which visual perception translates into social (and sexual) interaction—the three partners devised a host of basic but effective ways to encourage visitors to the High Line to view the city and its inhabitants from a variety of new perspectives. Rather than relying on traditional park benches or movable chairs in the manner of London and Paris parks, they designed several built-in seating areas, ranging from banquettes to recliners to stadium-style bleachers, which give the public a chance to stop and contemplate what otherwise might have seemed like a raised conveyor belt of pedestrians. And they abetted the universal pleasure of people-watching with devices as uncomplicated but potent as billboard-sized frameworks that confer on banal streetscapes the effect of the footage from a Martin Scorsese film that establishes place.

The firm’s transformation of New York’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (2003–2012) has given Manhattan another welcome series of instantly admired gathering spaces, epitomized by the Illumination Lawn, the new swooping greensward they built atop the Lincoln restaurant pavilion, set between Eero Saarinen’s Vivian Beaumont Theater of 1958–1965 and Max Abramovitz’s Philharmonic (now Avery Fisher) Hall of 1958–1962. This 7,203-square-foot expanse of tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass—rectangular in outline but gently contorted into a saddle-like shape (technically, a hyperbolic paraboloid) that touches plaza level at the lawn’s southwest corner—was immediately embraced by Juilliard students as their veritable campus center and by visitors who luxuriate in its open south-facing vistas and calming purity.

The administrators of Lincoln Center approached Diller and Scofidio shortly after Frank Gehry’s controversial plan for revamping the urbanistically flawed sixteen-acre complex—which advocated covering its principal plaza with a vast glass-and-steel canopy—was shelved in 2001. Unlike Gehry, Diller and Scofidio viewed the task as a series of delicate surgical interventions rather than a few large-scale impositions. (Their assessment of the issues at hand and their imaginative responses are well told in the new monograph Diller Scofidio + Renfro: Inside-Out, and Still Lincoln Center.)

Although the aging Lincoln Center was in urgent need of repair, a comprehensive overhaul struck some observers as throwing good money after bad, considering the dubious architectural quality of the complex and the estimated $1.4 billion price tag. The original architectural coordinator, Wallace K. Harrison (who designed its ever-garish centerpiece, the Metropolitan Opera House of 1958–1966), envisioned Lincoln Center as an acropolis elevated atop a continuous plinth over the several city blocks conjoined for the ensemble.

Owing to the gradually sloping site, the plinth is lowest at the main plaza entry facing Broadway but rises to a height of two stories on West 65th Street to the north and Amsterdam Avenue to the west. Its blank peripheral base walls killed an interesting street life around most of Lincoln Center, but this was Harrison’s intention. The adjacent neighborhood, which includes low-income housing due west of the Met, was deemed too dangerous to have any interaction with the center; the new cultural citadel unapologetically turned its back on the urban poor.

To make Lincoln Center more welcoming and accessible in a much-changed postmillennial Manhattan, Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro rethought the principal arrival sequence, which from the outset had been complicated by a service road parallel to Broadway. Attendees who came on foot had to negotiate oncoming traffic twice before reaching the plaza. In order to allow a smoother entry, the architects eliminated the service road, repositioned the vehicular drop-off point below street level, and extended a broad stairway (embellished with eye-catching messages from light-emitting diodes [LEDs] on the steps’ risers) over the new subterranean driveway, which is short enough not to feel like a claustrophobic tunnel.

The most welcome portion of their scheme has been the remaking of West 65th Street between Amsterdam Avenue and Broadway. That busy crosstown traffic artery was blighted for decades by the two-hundred-foot-long platform bridge that covered most of the block and linked Juilliard with the grand theaters to the south. Millstein Plaza, windswept and barren atop the span, never caught on as a public space and turned the street below it into an urban abyss. Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro’s bold decision to demolish this oppressive overpass was complemented by their creation of street entrances for each of Lincoln Center’s thirteen constituent institutions on 65th Street to increase pedestrian traffic on what had been a dark and forbidding no-man’s-land even at noonday. Activity is particularly lively at midblock, with its alignment of the entrance to Juilliard on the north side of the street and, directly across from it on the other side, the Elinor Bunin Monroe Film Center of 2011, designed by the Rockwell Group, with its façade done in collaboration with Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro.

Advertisement

Pietro Belluschi’s Juilliard School of Music of 1963–1969, with its longest elevation on the north side of 65th Street, was easily the best of the Lincoln Center buildings. Thus news that Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro planned a radical remaking of it was likewise cause for concern. The finest example of Brutalist architecture in New York City, the Juilliard building (with Alice Tully Hall, also designed by Belluschi, tucked into its lower portions) was hardly an approachable presence; but it did possess an integrity lacking in the sub-Neoclassical Modernism of Philharmonic Hall, the Met, and the New York State Theater.

Because Belluschi made Juilliard’s principal east-facing front parallel to the city’s grid plan rather than lining it up with the diagonal of Broadway, there was a capacious triangular plot left vacant at the northwest corner of 65th Street. It was here that the new architects cantilevered a 50,000-square-foot extension fifty feet over the sidewalk to diminish the bulkiness that would have resulted had the large addition touched down at ground level.

Beneath that new overhang the designers placed yet another of their signature rising banks of built-in seats, this time relatively small, made of concrete, and facing inward from the street corner to the remodeled building’s lobby and adjoining café. The designers made the new façade as transparent as possible, exposing, to the full view of passersby on Broadway, dance studios, musical rehearsal spaces, and classrooms, an effect particularly mesmerizing at twilight and after nightfall, when the vast glass elevation comes fully alive with all sorts of motion. This is architectural populism of the very highest order.

Reports of the renovation of Alice Tully Hall, the chamber-sized auditorium on the ground floor of the Juilliard building, were met in musical quarters with understandable cynicism after the unsatisfactory series of remodelings that the acoustically beleaguered Philharmonic Hall was subjected to almost from the day it opened. The sound quality of Alice Tully was never a problem comparable to the Philharmonic’s, but the tonal properties of the smaller hall have been noticeably improved by Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro’s collaboration with the acousticians J. Christopher Jaffe and Mark Holden.

The architects’ subtle, not to say subliminal, reworking of Alice Tully Hall (the performance space has now been renamed the Starr Theater) was also informed by what has been called “psychoacoustics”—the idea that our perceptions of a concert hall’s aural qualities are affected by the room’s appearance. Here the designers devised an ingenious illumination scheme whereby translucent wall panels of thinly sliced wood veneers are illuminated from behind by LED lights on computerized dimmers that impart an ethereal radiance—or “blush,” as the designers term it—to the perimeters of the auditorium. Eschewing the dated gilt-and-crystal of the older Lincoln Center theaters, this elegant space now glows with an inner warmth that seems at once atavistic and timeless, a Zauberfeuer (magic fire) worthy of Wagner, that wizard of synesthetic stagecraft.

3.

Ricardo Scofidio was born in New York City in 1935 and grew up in a small town in western Pennsylvania. He has said that his family never discussed its ethnicity, and apparently only in adulthood did he learn that some of his ancestors were black. He studied at New York’s Cooper Union, and after taking an architectural degree from Columbia returned to teach at his undergraduate alma mater where he is now a professor emeritus. Elizabeth Diller was born in 1954 in Lódz, Poland, to Holocaust survivors who emigrated to America when she was six. After receiving her undergraduate diploma from Cooper she enrolled in the school’s architecture program in 1976, where one of her teachers was Scofidio.

Their relationship moved from the professional to the personal, and Scofidio, who was married with four children, left his family and moved in with Diller. They set up their architectural practice in 1974, and were later married. Charles Renfro was born on the Texas Gulf Coast in 1964, studied architecture at Rice and Columbia, and joined Diller and Scofidio’s office in 1997. In an act of exceptional collegial generosity, the couple made him an equal partner and added his surname to their firm’s masthead seven years later.

Apart from their outstanding renovation work, Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro have also executed several start-from-scratch buildings that are as commendable for their economy as for their excellence in design. Their first American building, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) of 2002–2006 in Boston, offers a superb demonstration of the partners’ strongly urbanistic values. The ICA, founded as the Boston Museum of Modern Art in 1936, had occupied a series of converted spaces until it acquired a dramatic waterside site to the east of the city’s downtown business center on Harbor Walk soon after the millennium.

Before the advent of the ICA, this fifty-mile-long shoreline park, begun in 1984, had been little more than a pathway for joggers and cyclists. Although the derelict waterfront gave Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro a virtual tabula rasa, their client’s desire for maximum unobstructed exhibition areas (a must for the unpredictable display requirements of today’s new art) inspired the designers to lift the loft-like gallery area to the very top of the structure and create an inviting public space below it on ground level.

This organizing principle gives the pair of large rooftop display spaces—which measure nine thousand square feet each—pellucid natural lighting through thirteen rows of wall-to-wall north-facing skylights. Overhead trusses leave these galleries free of columns and allow the open spaces to be reconfigured as needed, making them among the most adaptable contemporary art spaces in America. The architects’ most decisive gesture was to cantilever that uppermost story sixty-four feet out toward Harbor Walk and the bay beyond. They thereby created a large sheltered public space beneath the overhang that has become one of the most popular outdoor gathering places in Boston.

There the designers installed the first version of what has become their most familiar and popular motif: the urban grandstand, with tiers of wooden bleachers on which pedestrians can sit and observe the passing parade. One gets a very good sense of the Boston gallery’s invigorating social aspect from Iwan Baan’s color photo essay in Diller Scofidio + Renfro: Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston, the latest installment in the Museum Building Series handsomely produced by the Spanish publisher Ediciones Polígrafa.

These socially attuned architects’ encouragement of people-watching emanates from their canny understanding that seeing and being seen—voyeurism and exhibitionism, if you will—are central to the civic transaction. That sense of how public spaces ought to be tailored to the behavioral patterns of their users is by no means confined to the firm’s two founding members. For example, it was Renfro who in 2012 secured the office’s commision to oversee the master plan for most of the commercial properties in Fire Island Pines, the largely gay summer resort off the south short of Long Island where he has often vacationed.

The Institute of Contemporary Art is furthermore noteworthy for its comparatively low price tag. In a period when $100 million museums have not been uncommon and many overreaching institutions are suffering the dire consequences of competitive, excessive pre-crash spending on new facilities, the 62,000-square-foot Boston structure was executed for a relatively thrifty $41 million. In comparison, Renzo Piano’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) of 2003–2008 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art cost $56 million even though it is only ten thousand feet larger than the Boston job (and a low-cost production for Piano, whose gemlike Nasher Sculpture Center of 1999–2003 in Dallas cost $70 million even though it is 17,000 square feet smaller than BCAM).

4.

Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro have a most demanding patron in Eli Broad, the Los Angeles tract house developer and financial services tycoon who hired them in 2010 to design the Broad, a repository for his collection of contemporary art that will be open to the public, now in construction next to Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall of 1987–2003 in downtown Los Angeles. Scheduled for completion in 2014, this commission has been fraught with ironies from the outset. Until just days before the opening of Piano’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum it had been assumed that the collector would give his extensive holdings to his eponymous gallery, but at the very last moment he announced that he was retaining ownership of his art after all.

Broad’s unexpected pullback shocked many observers, but cognoscenti were scarcely surprised. “Eli’s middle name is ‘strings attached,’” Christopher Knight, the art critic of the Los Angeles Times, observed on a 60 Minutes profile of Broad, and recipients of the meddlesome Maecenas’s funding have widely concurred. This self-styled “venture philanthropist”—a coinage that perfectly reflects his market-driven values—has given some $2 billion to cultural, educational, and other charitable causes, but he apparently expects that his largess also gives him the final word.

Broad twice hired and then fired Gehry (who vows he will never again work for the man he called a “control freak” on 60 Minutes), and Piano has made no secret that his BCAM scheme was badly compromised because of the donor’s rejection of the original light-filtering system as too expensive. Thus it will be interesting to see what this difficult client is able to accomplish with Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro.

Their plans for the $120 million new Broad—nearly twice the budget of BCAM, though at 120,000 square feet it is estimated at about $200 per square foot less than Piano’s design—are extremely promising, beginning with the building’s complex exterior, a honeycomb-like wraparound of glass-fiber reinforced concrete that brings to mind a larger-scale version of the cladding used by the SANAA group at their New Museum of 2003–2007 in New York.

Within, the architects plan to dramatize the sheer volume of the collector’s acquisitions—some two thousand works in all—with a looming storage unit they call “the Vault” at the heart of the structure, which will suggest vast unseen riches within. However, if the holdings displayed at the inaugural exhibition of BCAM in 2008 are any indication, Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro’s architectural container is likely to be more absorbing than the trend-following art assembled by Broad, who is seen by some in the art world as a “bottom-feeder” more concerned with name-brand bargains than premium quality.

Given the skill these designers have shown in integrating their schemes into an existing urban setting, in computer-generated renderings the Broad looks quite isolated behind the office wing of Gehry’s celebrated symphony auditorium. The completion of Disney Hall raised hopes that the environs of Bunker Hill in downtown LA, isolated by freeways, would at last become an active twenty-four-hour neighborhood instead of an enclave that comes to life only during performance hours, the same problem that plagued Lincoln Center until Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro’s revitalizing makeover.

Ambitious plans to transform Bunker Hill through the $3 billion Grand Avenue Project were approved in 2007 but the redevelopment scheme stalled when the Great Recession set in. Though the twelve-acre strip park linking the nearby City Hall and other municipal buildings is currently being opened to the public, well-founded doubts remain about the scheme’s prospects for success, given sharp cutbacks in commercial and civic investment. It will take more than a conventional park to establish and sustain around-the-clock street life in what has intractably remained a desolate ghost town after dark.

If only Diller, Scofidio, and Renfro were hired to give Bunker Hill the commonsensical but uncommonly imaginative character of their coups in New York and Boston. More than almost any of their current peers (with the notable exception of the collaborative Norwegian firm Snøhetta), they have repeatedly demonstrated a keen understanding of the social interactions that make for effective and enjoyable public spaces.

Scofidio, Diller, and Renfro are highly adept architects by any measure, but their keenest design skills are considerably deepened and intensified by a humane outlook of the sort usually ascribed to more earnest urbanists like Jane Jacobs and Lewis Mumford. This dynamic trio has a better feel for the workings of present-day New York than any other designers, and the way in which these prodigiously gifted late bloomers reliably upend rote responses to the contemporary urban condition makes them today’s shrewdest yet most sympathetic enhancers of the American metropolis.

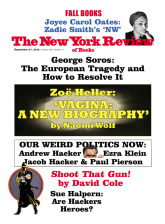

This Issue

September 27, 2012

Pride and Prejudice

Cards of Identity

Are Hackers Heroes?

-

*

See Martin Filler, “Up in the Park,” The New York Review, August 13, 2009; and “Higher and Higher,” The New York Review, November 24, 2011. ↩