You know the joke. A psychiatrist shows a patient a series of inkblots. Each time, the patient sees an erotic episode. “You seem to be preoccupied with sex,” the psychiatrist concludes. The patient protests: “You’re the one with all those dirty pictures.” Ask people to read the inkblots of American political life and that result, too, is likely to tell you more about them than it does about what is really going on.

Jamie Barden, a psychologist at Howard University, ran an experiment that demonstrated this very nicely. Take a bunch of students, Republicans and Democrats, and tell them a story like this: a political fund-raiser named Mike has a serious car accident after a drunken fund-raising event. A month later he makes an impassioned appeal against drunk driving on the radio. Now ask them this question: Hypocrite or changed man?

It turned out that people (Democrats and Republicans both) were two and a half times as likely to think Mike was a hypocrite if they were told he belonged to the other party.1 This experiment only confirms a wide body of work in social psychology demonstrating that we’re biased against people we take to be members of a group that isn’t our own, more biased if we think of them as the opposition. That’s not something most of us needed a psychologist to tell us, of course. The news is not that we are biased, it’s how deeply biased we are.

This disposition is evident enough in the coverage of the current president. Edward Klein’s The Amateur: Barack Obama in the White House is almost comically committed to seeing its subject in the worst possible light. This summer Klein told Steven Levingston in The Washington Post, “From the conservative point of view I’m a liberal, and from the liberal point of view I’m a conservative,” but his recent publications have included a book-length attack on Hillary Clinton and a self-published novel, The Obama Identity, written with the former Republican congressman John LeBoutillier, that depicts Barack Obama as a foreign-born former Muslim. (There is a plotline about the president’s foreskin, removed, of course, by a mutahhir, a professional Muslim circumciser, in Indonesia.) The Amateur concludes with a litany of dire facts that Republicans should publicize in order to defeat Obama. Those conservatives who think Klein a liberal are probably not paying attention.

Certainly, the rapturous reception of The Amateur among conservatives in the blogosphere must have something to do with the fact that it confirms the existing convictions of many on the American right. In Klein’s book, Reverend Jeremiah Wright recalls Barack Obama saying, “Help me understand Christianity, because I already know Islam.” One of the president’s “oldest Chicago acquaintances” asserts, “He is afflicted with megalomania.” Dr. David Scheiner, who was once Obama’s doctor, concludes, “He’s academic, lacks passion and feeling, and doesn’t have the sense of humanity that I expected.” The book presents exactly the picture of the cold and condescending crypto-Muslim so many Republicans already believe in.

Michael Grunwald’s The New New Deal, by contrast, advances the view that Obama’s stimulus bill, far from being a failure (a verdict shared by both Republicans and the left of the Democratic Party), provided both a Keynesian escape from a terrible economic depression and the “new foundation for growth” promised in the president’s inaugural address. So Democrats ought to like his book.

But is it mere bias that will make them think that, unlike Klein’s opus, it is full of detailed, careful argument, based on detailed, careful reporting and an impressive grasp of public documents? Surely not. It is possible to distinguish between partisan hackwork (even the kind that pleasingly confirms one’s own prejudices) and a work of serious reporting and analysis. If one is looking for the left-leaning counterpart to Klein’s demonology—and there are such works—one would have to look elsewhere.

Still, once we admit that the way we interpret evidence about politics and policy is shaped by our inevitable biases, it is probably a useful exercise to try to push against those biases. We might try to identify uncomfortable truths in work by those we disagree with. We might search out error in books by those we suppose to be on our “side.”

Klein begins his book with a one-sentence paragraph: “This is a reporter’s book.” Many reporters would beg to differ. This is, after all, the same Edward Klein whose 2005 book on Hillary Clinton—The Truth About Hillary: What She Knew, When She Knew It, and How Far She’ll Go to Become President—was denounced even by some conservative commentators for its sordidness. (Among other things, it suggested that Chelsea Clinton was conceived by rape.) Often his claims were about things his informants, many of whom were anonymous, were almost certainly in no position to affirm.

Advertisement

Despite having spent a decade as the editor in chief of The New York Times Magazine, he can seem resistant to factual correction. Two years ago, he wrote that when Benjamin Netanyahu visited the White House in March 2010, Obama snubbed him by leaving him to dine with his wife and daughters. As various people noted, the story had to be false, since the president’s wife and daughters were in New York City that evening. In his current book, undaunted by fact, Klein reproduces the anecdote.

Klein begins his long prologue with an extended anecdote that explains the source of the book’s title. It describes, in minute detail, a conversation between President Clinton and his wife, in the presence of a small group of friends in August 2011. As the first sentence has it, “Bill and Hillary were going at it again, fighting tooth and nail over their favorite subject: themselves.” The unnamed friends—Klein insists he has two sources for every fact he publishes—hear the ex-president urging his wife to run against the sitting president of her own party, on the basis of “secret” polls affirming her popularity; she would be able to “fix the economy.” Despite support from Chelsea Clinton, who according to Klein “wanted to wreak revenge against Obama’s campaign operatives who had dissed her mother and tried to paint her father as a racist,” the secretary of state was having none of it. “I’m the highest- ranking member in Obama’s cabinet…. What about loyalty, Bill? What about loyalty?”

“Loyalty is a joke,” Bill said. “Loyalty doesn’t exist in politics.” (Nor, if this story is to be believed, among the Clintons’ “old friends” who reported it.)

I’ve had two successors since I left the White House—Bush and Obama—and I’ve heard more from Bush, asking for my advice, than I’ve heard from Obama…. Obama doesn’t know how to be president. He doesn’t know how the world works. He’s incompetent. He’s…he’s…Barack Obama…is an amateur!

This story is, I suppose, consistent with the image many people already have of Bill Clinton: obsessed with political process as well as with policy, consumed with amour propre, a political operator who will sacrifice practically anything in pursuit of power, and so on. But is it credible?

Put aside the fact that the Clintons have, through their spokesmen, said it is false. Is it really likely that one of the great political strategists of our time would have proposed that the secretary of state should resign to run against an incumbent president of her own party? How would Klein’s informants know that Chelsea Clinton wanted to “wreak revenge”? For that matter, why would Bill Clinton have to rely on “secret” polling to confirm that his wife was popular, given that Gallup publishes data regularly on her ratings?

That the story’s dialogue and scene-setting are as stilted as the conversations in Klein’s novel—which features such characters as Mr. Piddlehonor and Whitney Nutwing—does not add verisimilitude. Nor is the plausibility of the book advanced by the fact that Klein has since floated another story about an attempt to get Hillary Clinton to replace Joe Biden as vice-president this time around.

In the spirit of the exercise I recommended earlier, though, here’s one uncomfortable lesson for Democrats that I drew from The Amateur. A lot of people who had supported Barack Obama feel disenchanted. Some, like Dr. Scheiner, are disappointed in Obama’s failure to create a single-payer national health insurance system (which Klein and Scheiner agree in calling “socialized medicine”). This is not so surprising. But some of his many acquaintances on the left are angry because he hasn’t given them the attention they think they deserve. Dr. Scheiner complains, “Obama invited his barber to his inauguration—his barber! But I wasn’t invited. Believe me, that hurt.”

Similar complaints have been widely circulated by many of the rich and powerful who have supported the president financially and politically in the past. Klein puts it like this:

He never called the people who had brought him to the dance—those who backed his presidential bid with their money, time, and organizational skills. The Kennedys didn’t hear from him. Oprah Winfrey didn’t hear from him. Wealthy Jewish donors in Chicago, who had helped fund his 2008 campaign, didn’t hear from him. The “First-Day People”—African-American leaders in Chicago who had paved the way for his political ascent—never heard from him, either.

Suppose, at least for the purposes of argument, that these claims have some truth to them. Klein is not the only one to suggest as much. He quotes The Washington Post’s Scott Wilson, who says that the president “endures with little joy the small talk and back-slapping of retail politics, rarely spends more than a few minutes on a rope line, refuses to coddle even his biggest donors.” Clearly many people across the spectrum think that he hasn’t done enough coddling. Klein devotes a chapter—called “Snubbing Caroline”—to the disaffection of Caroline Kennedy and her family. It is preceded by a chapter on his difficulties with Oprah Winfrey, “Oprah’s Sacrifice.” If the substance of these chapters is right—and, in view of Klein’s history, that “if” bears some emphasis—much of the information must have come from people close to these two powerful women.

Advertisement

On the other side, among Republicans, those who have met the president also seem to wish that he called them, too, more often. But they add that he isn’t much fun to talk to. Klein cites a much-quoted remark of Senator Pat Roberts, who suggested that the president was “pretty thin-skinned” and should “take a valium before he comes in and talks to Republicans.” Another unnamed “top aide to the Republican House leadership” complains, “Not only is he self-assured, the smartest guy in the room, but in his estimation all he has to do is state something and the scales will fall from your eyes…. If you challenge him, he’s furious. He gives you the death stare.” (Similar complaints are registered in Bob Woodward’s The Price of Politics.)

The existence of such gripes can scarcely be doubted. It’s true that Obama’s reputation before he entered the White House was as a careful listener and a deft conciliator.2 But then, in the meetings where he displayed these gifts, he wasn’t the boss. And he had a great deal more time to listen, since he wasn’t facing the daily raft of issues that land on the desk of a modern head of state. Some presidents—Bill Clinton and LBJ prominent among them—seem to have enjoyed the process of negotiation, a process in which you must often ingratiate yourself with your opponents. President Obama seems not to be one of them. There is, however, evidence that he is willing to devote his energy to finding solutions with like-minded people. That is one of the major lessons of Michael Grunwald’s engrossing book The New New Deal.

On February 17, 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), a stimulus package aimed to kick-start the economy. He had been in the White House for exactly four weeks. If getting the bill through Congress was a major political achievement, it is all the more extraordinary that it was put together so fast. Part of the story Grunwald tells is how the team that shaped the policies worked hard between the election and the inauguration so that they would be ready to spring into action. Many people—including many Democrats—think now that some of their principal policies didn’t succeed. Grunwald, a national correspondent for Time, aims to persuade them otherwise.

The New New Deal will, for the most part, please supporters of the president. But its author is a journalist, not a polemicist. In his “Note on Sources,” he sounds a cautionary note: “Sources lie. They embellish. They omit. They have agendas, hidden and not…. And sometimes their memories honestly fail them.” He warns that his book, inevitably, is “not the whole truth.” It includes thirty pages of densely printed endnotes; Klein’s has none. This is someone with a faith in factual reporting that Klein seems to have long discarded.

Grunwald argues, first, that the stimulus worked, and, given the speed and the political challenge of putting it together, worked remarkably well. It saved some jobs and created others. In a University of Chicago study he cites, only 4 percent of economists denied that the Recovery Act lowered unemployment. It’s true that unemployment remains high (7.8 percent is the current figure) and growth remains low (1.3 percent in the second quarter, according to the latest estimate). But many think that without the Recovery Act we might well have entered a depression. So if the point of the stimulus was to stanch the bleeding of the job market, it was a success, if a modest one. The act involved an unprecedented creation of new programs and an unprecedented expenditure of new funds at an unprecedented rate and yet there was remarkably little fraud and abuse. One reason was the existence of the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board (known as RAT) under the direction of a former policeman named Earl Devaney, who had been inspector general for the Interior Department. “Outside experts had warned that 5 percent of the stimulus could be stolen, but by the time Devaney finally got to retire at the end of 2011,” Grunwald writes, “the RAT board had documented only $7.2 million in losses, about 0.001 percent.”

His second central claim is that the bill laid the groundwork for many important programs that made good on the “new foundation for growth” promised in the president’s inaugural address:

We will build the roads and bridges, the electric grids and digital lines that feed our commerce and bind us together. We will restore science to its rightful place and wield technology’s wonders to raise health care’s quality and lower its costs. We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil to fuel our cars and run our factories. And we will transform our schools and colleges and universities to meet the demands of a new age.

As Grunwald points out, every item on this list appeared in the Recovery Act:

roads and bridges (Title XII), transmission lines (Secs. 301, 401, 1705), and broadband lines (Titles I, II), scientific research (Titles II, III, IV, VIII), electronic medical records (Title XIII), solar and wind power (over a dozen provisions), biofuel refineries (Title IV), electric cars (Sec. 1141), green manufacturing (Sec. 1302), and education reform (Sec. 14005).

Part of the interest of this book is in meeting the men and women who have worked to carry out these ideas. At the head of the team, providing Grunwald with much information, is a slightly manic Vice President Biden, who has been in charge of implementation of the Recovery Act. Biden’s enthusiasm shines through: “We’re talking about research that will literally revolutionize American life!” (Grunwald is not the first to notice that the vice-president often uses the word “literally” figuratively.) The vice-president ran twenty-two cabinet meetings, visited fifty-six stimulus projects, held fifty-seven conference calls with local officials, and in the two years after the bill was signed talked about the stimulus to every governor but Sarah Palin (who resigned before he had a chance).

Then there’s the “hard-charging energy secretary, Steven Chu,” the other Nobel laureate in Obama’s cabinet, who “had the toothy grin, dorky glasses, and wispy build of a tech nerd, but he had a steely side, too.” Inside the Energy Department, Grunwald tells us, a new agency has been created—the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA–E)—a “government incubator for high-risk, high-reward, save-the-world private energy research” with “an absurdly high-powered staff of braniacs.” ARPA–E’s budget took about 0.05 percent of the Recovery Act’s funding.

Among its schemes was the creation of an entirely new industry that uses tailored microbes to produce alternatives to gasoline (“electrofuels”) with an efficiency ten times greater than photosynthesis. Two years after the program began, one of Secretary Chu’s experts, Arunava Majumdar, was able to hold up two samples of electrofuel, produced by teams based at North Carolina State and MIT, at the ARPA–E summit in 2011. ARPA–E spent money that made an immediate contribution to the stimulus, but it was building, as the president promised, technologies that will eventually reduce our long-term dependence on oil. Another ARPA–E funded project, at Envia Systems in Silicon Valley, has improved battery technology. “The frustrating lead times of automobile production will keep this breakthrough off the streets until at least 2015,” Grunwald says, “but it could shave over $5,000 off the price” of Chevrolet’s plug-in hybrid car, the Volt. A third, MIT-generated venture, 1366 Technologies, aims to slash the price of silicon solar cells. “Majumdar calls 1366 the agency’s first grand slam, a game-changer for solar power.”

Even if the potential of these advances has been exaggerated, it’s dismaying that the only energy investment in ARPA–E most people have heard of is the bankrupt firm Solyndra, which made solar panels. Grunwald gives a meticulous account of how the loans to this firm were authorized and makes it clear that there were warning signs about the government’s investment. Still, he concludes, “after holding a dozen hearings, subpoenaing hundreds of thousands of pages of documents, and threatening numerous White House officials with contempt, Republicans have drawn a blank.”

The energy technology policies built into the Recovery Act have accelerated a process that was already underway. “In early 2009, the US ‘base case’ energy forecast expected it would take more than two decades for wind power to grow from twenty-five to forty gigawatts,” Grunwald writes. “It took less than two years.” Photovoltaic solar installations doubled in 2010. “By year’s end, the wind and solar industries employed nearly 200,000 Americans, more than the coal industry.” Ed Fenster of Sunrun, which puts solar power into homes in California, told Grunwald, “Solar was failing, and now it’s the fastest-growing industry in America.”

The New New Deal argues that buried in the Recovery Act were many programs that likewise were investments for the long term:

$90 billion for clean energy, $30 billion of health IT and other transformative health programs, $8 billion for education reform, $8 billion for high-speed rail, $7 billion for broadband, and $7 billion for unemployment modernization.

In general, Grunwald may be too willing to accept the administration’s view about the worth of these investments. It’s notoriously difficult to predict which efforts at technological innovation will pan out. Owing to political resistance, few of the high-speed rail projects are being built; the efficacy of the administration’s approach to education reform is in dispute. Yet even if you dial back Grunwald’s optimism, you’d have to conclude that the president has done a poor job of explaining his own achievements. “The rap on Obama in 2008 was that he was a words guy, not a deeds guy, a great communicator but an unaccomplished legislator,” Grunwald writes. “It turned out that he was more of a deeds guy.”

The “professor-in-chief,” he says, hasn’t succeeded in educating Americans about Keynesian stimulus. The Recovery Act, even if half as successful as Grunwald thinks, should have been heralded as an achievement; instead, the aura of failure lingers and “stimulus” has become a taboo word in the political lexicon. (It’s no accident that the president’s acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention made no mention of the stimulus bill.)

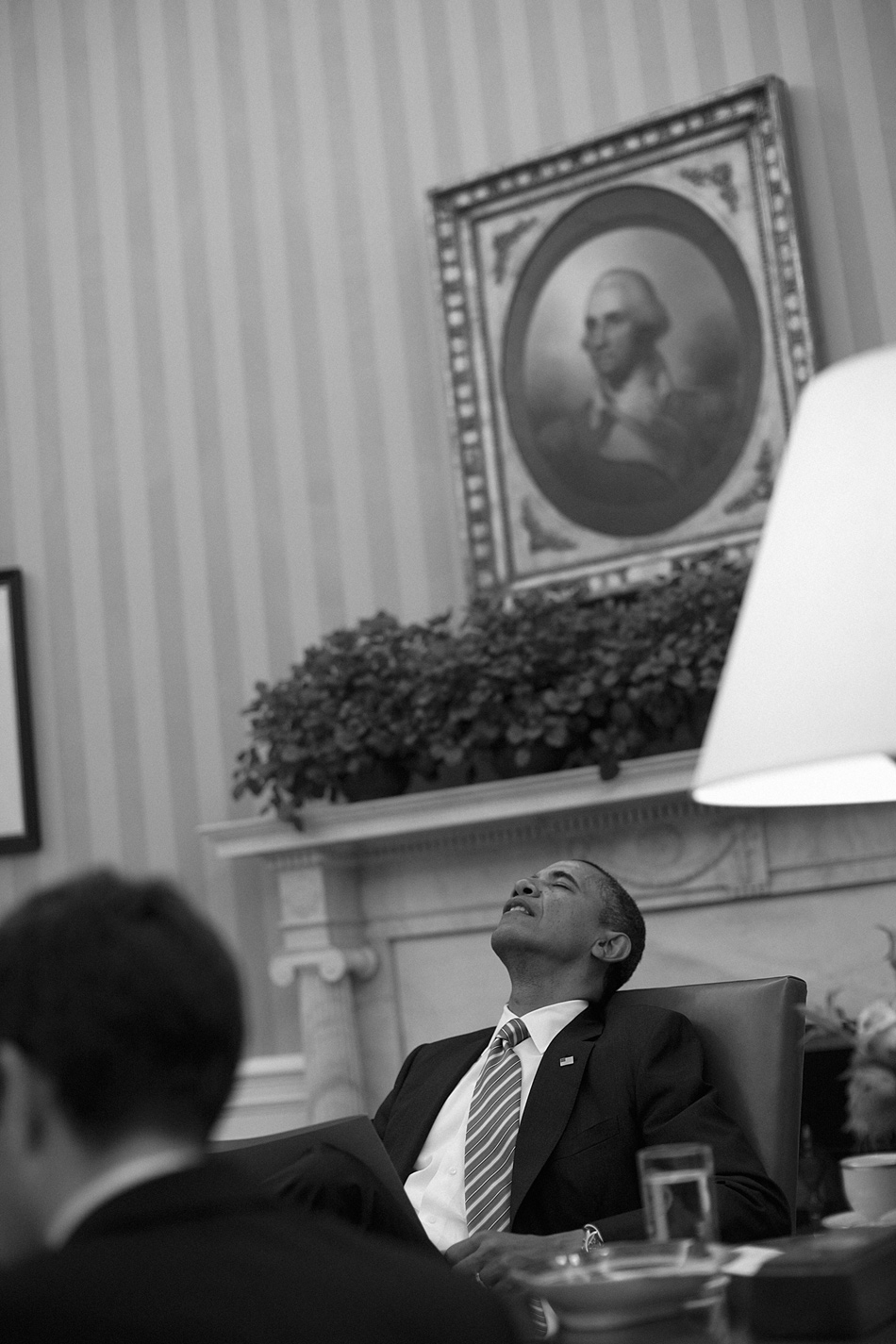

Grunwald has talked to a great many people who have worked with the president, even if he never got to interview the man himself. His impression, based on those many conversations, is that President Obama is pretty much the man he appears to be. “My sources,” he writes, “mostly describe the same cerebral, low-blood-pressure, somewhat aloof alpha male. They marvel at his uncanny ability to boil down a meeting to its essence.” But his aides also acknowledge that “there’s something vaguely enigmatic about their boss. He’s so modulated, so left-brain, so unruffled. They admire him, but they’re not sure they truly know him.” He can appear remote and disengaged. A man who is not especially needy himself can fail to respond to the needs of others.

So, oddly, I came away from The New New Deal with the same worry that I took from The Amateur. Mitt Romney has often been accused of running away from his own principal accomplishment as the governor of Massachusetts, “Romneycare.” But something similar could be said of Obama, whose opponents have made the Recovery Act, as well as the Affordable Care Act, into a political tar baby. When Mitt Romney scoffed in the first debate that half of the green energy companies supported by the federal government had failed, anyone who had read The New New Deal would have wondered where the governor was getting his facts from. They might have been less surprised that the president did not rise to the program’s defense. Something in the president’s personality may be getting in the way of his persuading the people, inside and outside Washington, whom it’s his job to persuade. That, at least, is one reading of the inkblots.

-

1

Jon Hamilton, Alix Spiegel, and Shankar Vedantam, “Inconsistency: The Real Hobgoblin,” Morning Edition, NPR, March 5, 2012. ↩

-

2

I did a program for the BBC after President Obama was elected, which led me to talk to many of the scholars who had worked with him. This was a repeated theme of their comments. “Obama: Professor President,” BBC Radio 4, January 6, 2009. ↩