Within a year of George Bellows’ s sudden death, in 1925, at age forty-two—from complications from a ruptured appendix—Sherwood Anderson, writing in Vanity Fair, put his finger on a salient quality of the realist painter’s work. Looking at some of the artist’s last pictures, which were large and vaguely anachronistic double portraits, Anderson implied that the point Bellows was making with them wasn’t altogether clear, but had he lived, and gone on to other pictures, their meaning in the larger scheme of all his work might have become apparent. He concluded that the paintings were saying that “Mr. George Bellows died too young. They are telling you that he was after something, that he was always after it.”

Anderson’s quote, which appears on a wall label toward the end of the current Bellows retrospective, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, perfectly captures what viewers, taking in the artist’s justly acclaimed early scenes of a gritty and dynamic New York in the years around 1910—and his more purely artful later explorations of many different genres—may feel: that there was a remarkable restlessness, drive, and desire to experiment in Bellows. Anderson’s leaving unsaid what the painter was going after hits home as well. For in Bellows’s art one finds, especially in his early pictures, which are among the most beautiful made by an American, that his subject is elusive. It seems to be simply (or not so simply) an exuberance in being alive.

Bellows is most associated with the brushy and lustrous realist painting, with its feeling for public life—for surging crowds and commotion-packed doings in densely populated tenement streets—that held sway in New York in the years before World War I. Not long after he came to the city, in 1904, at twenty-two, from Columbus, Ohio (where he left Ohio State before graduating), Bellows became a student at the New York School of Art. There the tall, well-built, sociable, and brainy young man, who, back home, had excelled in a number of sports and played semipro baseball, was soon under the spell of Robert Henri, who essentially created the idea of an American realist art.

Stronger as a teacher and writer than a painter, Henri had a genius for getting beginning artists to believe in themselves. (His catalytic power, which owes a lot, I believe, to Emerson essays such as “The Poet” and “Self-Reliance,” can be felt in passages throughout The Art Spirit, his 1923 collection of class talks and articles.) Henri urged his friends and followers, including John Sloan and George Luks, and his students (among whom Bellows became the star), to take as their subject life as they encountered it, no matter how inartistic it might seem at first. It was Henri who got American painters to make pictures about barbershops, gatherings in Central Park, the city’s new immigrant communities, or dust storms on Fifth Avenue.

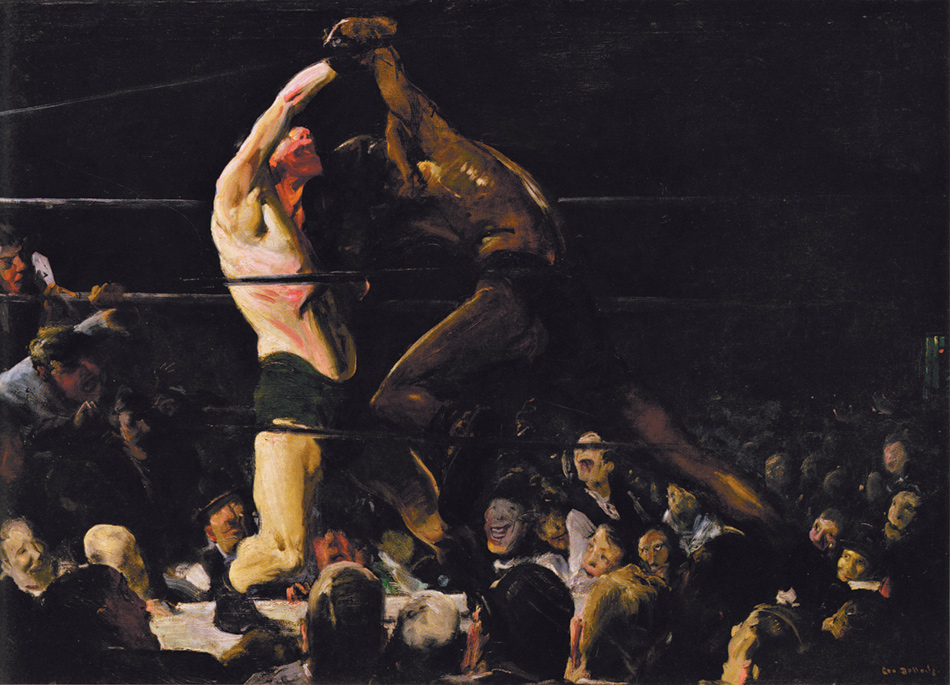

Bellows followed through with, most famously, his 1909 boxing pictures Stag at Sharkey’s (which is in the Met’s exhibition) and Both Members of This Club. Showing bloodied and thrusting, angular bodies in theatrically darkened settings, these visceral and large-size pictures, where we cannot quite make out the faces of the boxers but see the coarse and grinning faces of the audience members, have long felt like signposts in our national history. They seem to epitomize an era when a degree of brute, barely regulated force colored many aspects of American life.

Along with other New York paintings and drawings that he was making at this time—whether of boys fighting on tenement streets or the hubbub of an election night in Times Square—Bellows’s boxing pictures, at the very least, have a breadth and a sense of daring that no other American realist, or naturalist, art can match. It was Bellows, moreover, who, inadvertantly, was responsible for these New York artists being labeled the Ashcan School. It happened when a published drawing of his of hoboes appraising pickings from a trash bin was remarked on by a cartoonist out to make a derogatory point—though surely the thought of there being an Ashcan School, and the very sound of the words, make for one of the funnier and sweeter names attached to any group of American artists.

Yet Bellows, like Edward Hopper, his friend, exact contemporary, and classmate at the New York School of Art—and like the younger Stuart Davis, who joined the school after Bellows left—had work he wanted to go on to after the ashcan days had run their course. And this Bellows, like Hopper and Davis, was an artist who, while attached to American subject matter, insisted on a highly-structured, or keenly formal, underpinning for those subjects. Hopper bolstered his American vistas with a feeling for a geometric clarity and severity, while Davis draped American themes on Cubism’s scaffolding.

Advertisement

Bellows, in turn, as scholars in recent years have made clear, was almost in thrall to color theories and principles of pictorial organization, such as the golden section, where elements in a picture (trees, perhaps, or buildings) are placed to give the entire scene an inner balance and tension. This concern for a universal or mathematical order manifested itself in his life as well as his art. The lines of the vacation house he would eventually build for his family in Woodstock, in 1922, for example, presumably hew to the concept of Dynamic Symmetry, an idea developed by Jay Hambidge, one of a number of theorists whose thinking Bellows followed. How noticeable Bellows’s underlying compositional schemes are for viewers is another matter. These strategies don’t exactly jump out at you.

Especially in the Woodstock-area landscapes from his later years, though (which are unfortunately underrepresented in this show), Bellows’s color and design sense can have a peacocky flamboyance, making for pictures that, intriguingly, seem equally to be visions and confections. And the fact that there is a world of measurement and color theory buried in Bellows’s pictures may help account for the increased interest in his work on the part of scholars and curators in recent years. It possibly helps explain why three major institutions wanted to do the enormous present show, even though there was a substantial exhibition, if only of Bellows’s paintings, as recently as 1992. (It was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, and traveled to the Whitney.)

For many of the writers contributing to the catalogs of that show and of the current retrospective, Bellows’s involvement with various pictorial systems is of a piece with other overlooked aspects of his approach: his generally doing many painted versions of a given image, his often rethinking an image in drawings and lithographs, and his awareness of old master paintings. According to Franklin Kelly, the deputy director and chief curator of the National Gallery and the person who got the current show underway, it is important to note that Bellows was a “methodical” artist even in the celebrated early days of his career (when he was presumably thought to have been a more purely “spontaneous” creator). Methodical would certainly describe the way, when he was covering New York as an acolyte of Henri, he produced a number of similar boxing pictures, or a handful of related pictures of the excavation that led to the building of Penn Station.

A great deal of studiousness and industry is unquestionably evident in Bellows’s subsequently immersing himself, during his last fifteen or so years, in seascapes, portraits, landscapes, and such topics in contemporary life as tennis matches at Newport, the evangelist Billy Sunday, civilian casualties in World War I, and the Dempsey–Firpo bout of 1923. For Charles Brock, also a National Gallery curator and the chief organizer of the present exhibition, Bellows, in his involvement in so many aspects of his time, and in his almost detached way of treating them, is more than the bright light of American realism. He is a grander, if less clearcut, figure than that. Kelly suggests that, in his bringing together of the “banal and grand, and the everyday and the timeless,” he is even a version of the “painter of modern life” that Baudelaire wrote about. In the exhibition’s view, Bellows is both a traditional and a modern artist, and one whose significance becomes more apparent when his entire, though tragically truncated, career is accounted for.

In the years after his death, however, it was Bellows’s early New York pictures that mattered. His formal concerns were not an issue and his later work was lost sight of. My own view, as I have been suggesting, is that this judgment is still sound. Viewers who missed the 1992 show, or have never seen many of Bellows’s early pictures in one place, may be surprised by how luscious and delicate, as well as muscular, a painter he was when he was starting out. His choice of themes was undoubtedly spurred by Henri; and surely there is something disjointed in the way he jumped from recording the faces and doings of young people he knew or saw in the streets to boxing scenes, and went on to images of Manhattan construction sites and waterfronts. Yet helped along by the boldness and variety of his brushwork and his sometimes brassily sharp color, he gives us, even with his few and disparate themes, a lived-in, breathing sense of New York at that time.

Advertisement

When Bellows left Columbus he took with him the skills, which he had been working on since grade school, and honed at Ohio State, of a caricaturist and illustrator. In New York he was working with oils on canvas in a serious way for the first time, and the excitement of paintings such as River Rats, Beach at Coney Island, Kids, and Forty-two Kids (which all date from 1906 to 1908) comes in part from watching a practiced draftsman (with a huge ego) commandeer a new and very different art form.

In these wonderful paintings of boys and girls skirmishing in the dusk in an alley, or making out on a crowded beach—or standing with clenched fists and bawling, or taking it all in philosophically, a cigarette dangling from this or that mouth—we are responding to a cartoonist who is used to fashioning images with speedy abbreviations encountering the sluggish medium of oil paint. The resulting pictures are especially engaging when seen close up, because faces, limbs, and hats all seem to have been formed in dashing new ways.

Forty-two Kids, an East River scene where our mostly naked or stripping heroes are busy jumping in the water—or studying one another, or contemplating their penises, or lying on their backs and smoking—is the most extraordinary of Bellows’s group pictures of young people. Showing these many little, bright bodies clambering over a shambles of a grayed pier, which is set against a very dark East River, the painting, it dawns on a viewer, is a feat of design and planning. It is a picture that can be looked at and savored, if only for the body positions Bellows has devised, for a long time.

What Forty-two Kids is about, other than portraying a moment, is hard to say. Viewers may find themselves thinking of Eakins’s celebrated painting Swimming (1884–1885), where a number of adult naked male swimmers are seen at a distance and are as poised and elegant as figures in classical Greek art. Eakins didn’t say this, but his painting, we can feel, is somehow about yearning. It seems as sad as it is exquisite, and its presence in our minds as we take in Forty-two Kids reinforces our sense that Bellows’s picture, beginning with its lean, plainspoken title, is like an opera without a libretto. It is a picture with no graspable psychology, which isn’t to say that it is less a work than Swimming.

Bellows’s views of the Hudson or the Battery on bright winter days after heavy snows, or Riverside Drive or the East River on cloudier days, similarly stymie us as we try to account for their power. With smoke, trees, snow, shadows, stonework, sunlight, and water all rendered with a sparkling velocity, the subject of the pictures might be energy in itself. Viewers who have a sense of these sites may feel, standing before paintings that are generally around four feet wide, that they want to walk right in.

Bellows’s art, though, began to change shortly thereafter. In 1911 he made a huge painting called New York, a view of no actual location, packed with buildings, vehicles, and pedestrians. It is like an all-out effort to summarize the city, and much of it is impressive, especially the way the painter, in blocky little passages probably made with a palette knife, suggests things vaguely seen in the distance. The people trudging along at the bottom of the picture, however, perhaps for the first clearly noticeable time in Bellows’s art, have a generic, and unfelt, appearance.

And from roughly this moment on, to the detriment of his work, the figures in his pictures, whether they are stevedores on New York docks, shipbuilders or boatsmen in Maine, or boxers and spectators in his later pictures of the ring, have increasingly the presence of stock types. Conventionally beefy and hearty, or willowy and genteel, or ramrod straight and noble, they have a commercial-art presence that keeps us at a distance. The figures are all too kin to the overly stylized straw people in the paintings of the same years by Rockwell Kent, another classmate of Bellows from the New York School of Art.

But the issue isn’t only that the people in Bellows’s scenes became unconvincing. One feels that, around 1911, as he was about to be thirty—and, as it happened, had recently gotten married (to Emma Story), and purchased a house on East 19th Street—Bellows became complaisant in his self-assurance. He never lost his desire to challenge himself, but his goals became conventional. His portraits from this time on, for instance, are strangely old-fashioned. He characteristically went about making them with great industry, and it comes as a surprise to realize that while his boxing pictures firmly link his name with aggressive masculinity, his most considerable later portraits, which were often of Emma, and later of their two daughters and his mother and aunt—and show few men in general—take us into a world not only of women but of rather resigned women.

With settings for the portraits that are often darkened and hushed, Bellows seems to be aiming, essentially, for an emotional and artistic decorousness. His numerous seascapes, begun around 1911 and done mostly from trips to Maine, also miss the spark of something personal. These images of dark green water, crashing waves, and lacy foam have all the externals right and no inner life.

When Bellows returned, in the middle Teens, to the theme of boys on New York docks, or went on to such subjects as boxing or the evangelist Billy Sunday, his pictures seem indistinguishable from magazine illustrations. His drawing style and paint surfaces feel merely manicured. His series of large paintings (and many works on paper) from 1918 about the German army’s brutal treatment of Belgian civilians in 1914 have, at least, a genuine vehemence. A painting where a boy’s hands have been chopped off by the barbaric invaders is shocking, and one involuntarily salutes Bellows for the ambition that went into these pictures. Barely part of his 1992 show (but in full force in the present one), the pictures are infrequently seen, in part because the accounts of German atrocities were later shown to be overblown or bogus. Even if the stories had been true, though, Bellows’s treatment of this material is melodramatic, and his figures feel mannered and gleamingly overlit.

Is there a real difference between, on the one hand, the bullish dockworkers, the Maine folk, and the waddling urbanites of Bellows’s later work and, on the other, the mostly young people in his early New York scenes? Might it not be said that those roughhousing kids, and the louts and meatheads at ringside in the boxing scenes of the same time, were just as much the stylized creations of an illustrator-painter?

Oddly enough, I think these earlier figures have a greater authenticity because Bellows was then even more of an illustrator. He had, at the time, barely moved beyond his experience as a college-age caricaturist (which included being initiated into a fraternity), and he was primed to rib his new subjects. It was second nature for him to show people as oddballs, or vaguely damaged, or hunched over, or darting about. He does so even when, in masterful drawings of the moment such as Dance in a Madhouse or Mardi Gras, his subjects were older people—or when, in his big riverfront or construction site scenes, he puts in little, distant figures here and there. And these often gangly revelers, with their raw yet telling faces, add something fervent and charming to the history of painting, whether American or European.

Bellows’s portraits from his beginning years in the city are not as renowned as Stag at Sharkey’s, or even Forty-two Kids or the river scenes, but they shouldn’t be overlooked. The 1907 Frankie, the Organ Boy, of an awkward, happily open-faced blond, may be the most commanding of them. Looking at it, we immediately feel Bellows’s loving regard for the street musician, his desire to josh the boy, and, in his treatment of Frankie’s seemingly cockeyed features and enormous hands, his devil-may-care attitude toward immediate legibility. Frankie remains a kind of unlikely marvel. But that might be said of many of the pictures Bellows made when he was first responding to life in New York.

This Issue

December 6, 2012