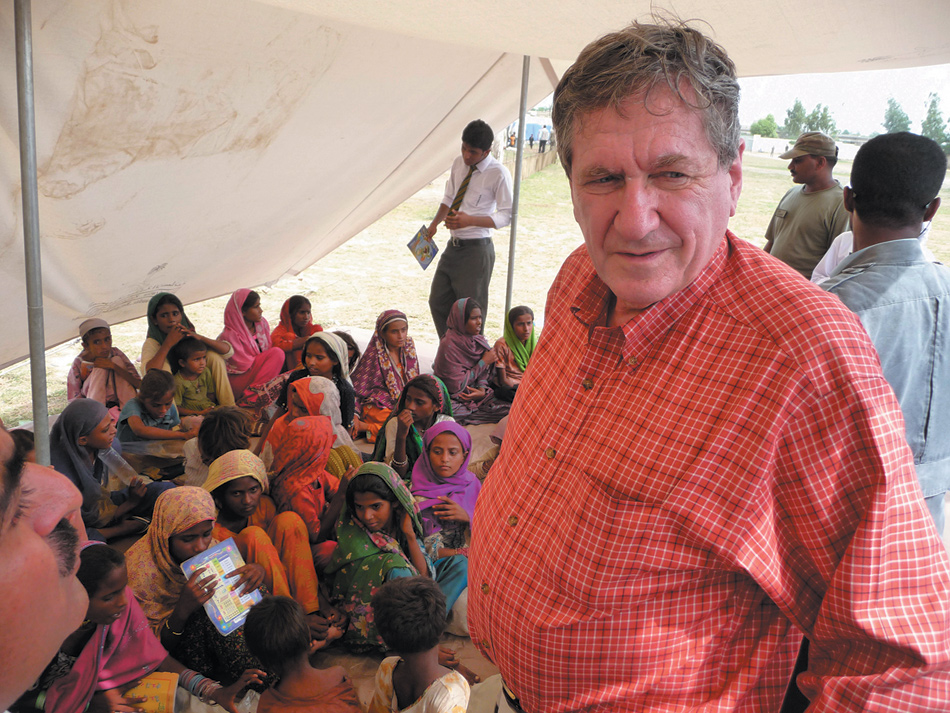

For the last decade or so, Vali Nasr has published original, pragmatic work about Middle Eastern politics. The Shia Revival, his 2006 book, confidently mapped how the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq strengthened Iran and reanimated sectarian conflict in the Arab world and beyond. Forces of Fortune followed three years later; it described presciently the potential of Arab middle classes just before Tunisian, Egyptian, and Libyan urbanites helped ignite the “Arab Spring.” By that time Nasr had entered the State Department as a senior adviser to Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, whom President Obama appointed as a special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan. After Holbrooke died suddenly in December 2010, Nasr left the State Department and in 2012 became dean of the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington.

In The Dispensable Nation, Nasr dissects what he regards as the overlapping failures of the Obama administration’s foreign policies across the Middle East and South Asia, from Pakistan to Iran to revolutionary Egypt. The book begins as a detailed, analytical memoir of disappointment over how “a small cabal of relatively inexperienced White House advisers” undermined Holbrooke’s diplomatic mission in South Asia, as Nasr looked on. The author then embarks on a withering review of first-term Obama administration diplomacy.

He concludes with criticism of Obama’s most important foreign policy conception, the announced American “pivot” toward Asia and away from the Middle East, a reorientation of policy, alliance priorities, and military deployments made possible by the reduction of American involvement in the wars Obama inherited in Iraq and Afghanistan. Most provocatively, Nasr argues that by retreating from the Middle East—and by signaling a withdrawal from “the exuberant American desire to lead in the world”—Obama has yielded strategic advantage to China, for which the United States will pay a heavy price in the future.

Nasr writes that he did not want to use his book as “a political bludgeon,” yet he describes Obama as a “dithering” president prone to “busybodying the national security apparatus” who allowed Holbrooke, in particular, to be marginalized at the White House in an internecine “theater of the absurd.” At the same time, the author offers only hagiographic generalizations about his bosses, Holbrooke and Hillary Clinton, “two incredibly dedicated and talented people” who “had to fight to have their voices count.” When things went badly for Obama, the administration “knew [Clinton] was the only person who could save the situation, and she did that time and again.” This uncritical, not to say hackneyed, view of the secretary of state is difficult to reconcile with the fact that she helped formulate, and often enthusiastically sold in public, the very Obama administration policies that the author finds so wanting.

Nasr has serious arguments to make. Some of them are detailed and deeply informed, as in his brilliant and important chapter on Pakistan, but others come across as more hurriedly composed. What finally recommends the book is the very quality that often makes it jagged: Nasr’s willingness, as a well-positioned insider, to attack viscerally the complacent belief among Obama and his national security advisers that they have constructed a rare left-leaning presidency that is tough-minded, restrained, and above all effective on foreign, defense, and counterterrorism policy. Along the way, Nasr offers confident views about America’s place in the world; its capacity to influence South Asian and Middle Eastern nations in crisis; and rising geopolitical competition with China. Unusually in Obama’s Washington, where muted loyalty to the president has generally prevailed among Democrats, Nasr has written a pugnacious book. Of greater interest, however, is to what extent his arguments about Obama’s forays into the Middle East may be right.

Because Obama’s aim has been to “shrink [America’s] footprint in the Middle East,” Nasr writes, the president’s approach to the Arab Spring

has been wholly reactive. It may get a passing grade in managing changes of regime as old dictators fall, but it has largely failed at the real challenge, which is to help the new governments…move toward democracy and reform their parlous, sclerotic economies.

Here as elsewhere in his book, Nasr employs a “to be sure” form of argument to challenge what he sees as Obama’s passivity. To be sure, that is, “there is plenty of evidence today that the Arab Spring will produce illiberal new regimes” that warrant caution. To be sure, “there will be civil wars, broken states, sectarian persecutions, humanitarian crises,” and other intractable difficulties. To be sure, Europe’s sovereign debt crisis and America’s fiscal hole after the worst recession in three quarters of a century left the West with shallow resources and inward-looking politics just when Arab populations rose up against their oppressors. And yet, even so, Obama should have done much more after the Tunisian revolution began late in 2010, Nasr believes. And because of Obama’s hesitation, it is impossible to “say now that the Arab Spring would have been such a disappointment had we engaged with the region quickly and forcefully.”

Advertisement

By “engagement” Nasr means a Marshall Plan–scale package of economic aid on par with the more than $100 billion the United States poured into formerly Communist Europe in the decade after the Berlin Wall’s fall. “It is true that the global financial downturn and the Greek crisis had left little for Cairo, but that is no excuse. Egypt is a hinge upon which the fate of the whole Middle East may turn.”

Is this a realistic basis for criticism of the Obama administration? Nasr’s case is that “Egypt’s best chance for real change came early, right after Mubarak left. That is when America and its allies should have put a big financial package on the table in exchange for big changes.” Yet even if Obama could have waved a wand and summoned such sums from Western, Persian Gulf, and Asian treasuries, there are many reasons why an effort to leverage large-scale aid in order to win private-sector reforms in Egypt might have failed, as Nasr readily acknowledges.

The Egyptian military enriches itself from state-owned industry and resists market reforms skillfully. Nationalist and anti-American strains of Egyptian politics have long undermined outside economic reformers from the International Monetary Fund and elsewhere. After Mubarak’s departure from leadership, Egyptian politicians, trying to win votes, competed to be more nationalistic and anti-American than ever. Besides, are we really to regard shock capitalism, Washington’s direct economic intervention, and major foreign financial flows as solutions to Egypt’s endemic woes of corruption, sectarianism, police-state thuggery, unemployed youth, and poor education? The records of weak states suddenly doused with dollars—Afghanistan in wartime, recently, or petro states of sub-Saharan Africa such as Nigeria and Angola—are not causes for optimism.

Nasr describes well the contradictions in the Obama administration’s responses to the Arab revolts and revolutions of 2011. The administration tilted toward those Arab revolutionaries who seemed most likely to prevail against their dictators—in Tunisia and Egypt—but then held firm to guns-for-oil alliances with the autocratic royal families of Saudi Arabia and smaller Gulf states, where the political status quo seemed likely to hold. In Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, Obama initially managed to irritate both the aspiring revolutionaries and the presiding royals. In Libya, Obama ceded to France the leading role in providing external support to a revolution whose outcome is still murky. The president tacked back and forth in reaction to the chaotic revolts in Yemen and Syria. His administration’s policy was certainly “confusing and unconvincing,” as Nasr puts it.

It eventually became clear that Obama would back successfully oppressive Arab dictators friendly to the United States, but not unsuccessful or unfriendly ones. Such situational contortions of principle understandably frustrate Nasr, but they are hardly a new feature of American engagement in the Middle East. “If we don’t think the region is in the throes of historic change, why embrace the Arab Spring at all?” Nasr asks. He wishes for “a vision or a grand strategy to guide America’s response to the cascade of events.” Yet his recommendations of nation-building and generation-spanning economic aid would require a checkbook and bipartisan support that the Obama administration simply did not possess.

Nasr is too well informed and subtle an analyst to gloss over the complexity of his subject matter or the problems with his own bold arguments. In one passage, he makes a clearer case for Obama’s regional policy than the president or his aides typically offer in their own defense:

If there is any American strategy at play in the Middle East these days it can be summed up as follows: Keep Egypt from getting worse, contain Iran, rely on Turkey, and build up the diplomatic and military capabilities of the Persian Gulf monarchies. In other words, play defense with regard to the Arab Spring, play offense when it comes to Iran, and maintain continuity in waging the war on terror.

Nasr finds many faults with this “realism,” as some of Obama’s aides would style it. It is certainly not an imaginative group of strategies. Yet from the perspective of Americans struggling with high unemployment and nursing young wounded home from Iraq and Afghanistan, Obama’s reticence may seem to offer ample wisdom.

Arguably, the most urgent case for renewed American activism in the Middle East today lies in Syria, in response to a grave humanitarian crisis that is burdening and endangering American allies in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon. Liberal and neoconservative interventionists want Obama to step in militarily, to protect civilians, reduce sectarian violence, contain al-Qaeda–influenced groups, and thwart Iran and Hezbollah, which are fighting as proxy allies of Syrian President Bashir al-Assad.

Advertisement

Yet Nasr does not join with the interventionists or advocate a plunge into Syria’s civil war. In general, he argues, the Pentagon and the Central Intelligence Agency have too often persuaded Obama to embrace military and covert interventions in the region, when diplomatic and economic investment would be superior. Nor does Nasr dwell on another commonly criticized aspect of Obama’s Middle East record, his administration’s accommodation of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who continues to authorize settlements in the West Bank and sidestep attempts to revive the Israeli-Palestinian peace process.

Nasr instead locates his major criticism of the Obama administration’s Middle East policies in its conduct of Great Powers strategy. “We not only have to remain fully engaged with the Middle East, we have to increase our economic and diplomatic footprint there to match our show of military force,” he writes. The reason, he believes, is China’s rise. A “retreat from the Middle East will not free us to deal with China,” he argues, but instead, “it will constrain us in managing that competition.”

In the late 1960s, a fiscally strapped, post-imperial Britain pulled back from the Arab world and invited the United States to fill the gap. The US was expected to secure oil supplies for all the world’s free-market economies and to keep the Soviet Union at bay. Nasr fears that a similar changing of the guard is now underway, and that energy-hungry China

will soon welcome the American exit from the region even at the cost of shouldering the security cost itself. American retreat from the Middle East will be welcome in China as a strategic boon; and this is exactly why it should not happen.

Nasr cites some work I published recently describing China’s “mercantile” attitude toward oil supplies in Africa and the Middle East.1 He cites this Chinese activity as evidence that Beijing may seek to replicate America’s position as a security guarantor and privileged oil customer of Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf producers. Actually, my own view is that it is just as likely that China’s attempts to lock up far-flung oil supplies exclusively will be abandoned because they will prove to be irrational and self-defeating.

Partly this is because of the accelerating pace of technological change in the energy industry. Horizontal drilling and other new extraction techniques are unlocking extensive new oil and natural gas supplies in the Americas and elsewhere. Truck fleets fueled by natural gas and investments in better batteries for automobiles may well upend the global transportation industry—and therefore world oil markets—during the next several decades. It is hard to foresee how these changes might spread but the history of energy innovation cautions against extrapolating past patterns in a linear fashion. Whatever China’s position as a world power in 2030, it is not likely to replicate America’s place in the oil geopolitics of the late twentieth century. Equally, cyberspace and outer space look to be more important to China’s future projection of global military power than control of the Straits of Hormuz.

Middle Eastern oil will remain an important part of the world economy for decades, but it seems premature to worry, as Nasr does so acutely, that China will have better luck than America did managing the Arab world as a kind of instrumental gas station. Even if Nasr is correct that China hopes to secure long-term fossil fuel supplies by intervening in Arab and Iranian politics, an American might offer the sort of exhortation that Russian diplomats uttered when the United States went barreling into Afghanistan late in 2001: Good luck with all that.

The Dispensable Nation is strongest when Nasr lays into the Obama administration’s policies in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran, three countries he knows exceptionally well, and on which he worked day-to-day at the State Department. The journalists Ahmed Rashid, Bob Woodward, and Rajiv Chandrasekaran have earlier chronicled the infighting over policy and ego between White House aides and Holbrooke’s team in 2009, as President Obama ordered thousands of additional American soldiers to fight the Afghan war.2 Nasr confirms these accounts and adds new details. He also synthesizes his memoir with a number of fresh arguments about why the “surge” of troops Obama ordered into Afghanistan failed to achieve the expansive goals military leaders set out.

Nasr chronicles Obama’s growing ambivalence about the counterinsurgency doctrine he was being sold—and oversold—with enthusiasm by the Pentagon. This instinctive skepticism caused the president to slow down and seek less grandiose military deployments—but not to abandon the surge altogether. Where Nasr sees “dithering,” others may see a learning president who realized that his own promise during the 2008 election campaign to support Afghanistan’s “good” war with new troops may have been premature, and who understandably recoiled from the car showroom sales techniques of Pentagon counterinsurgency enthusiasts.

In any event, there can be no question, as Nasr argues, that the half-measures Obama chose at the end of his policy reviews in 2009—announcing a withdrawal date at the same time that he ordered fresh troops in, and keeping the numbers of troops too low to be able to fully blanket Afghanistan—did contribute to the Taliban’s ability to wait out the American-led assault, and to achieve the strategic military stalemate that now prevails, at a high cost in American blood and treasure.

Obama ceded Afghan strategy in substantial part to General David Petraeus, an understandable decision given Petraeus’s record and stature. Petraeus served in three roles during the president’s first term—as overall commander of US forces in the Middle East and Central Asia, as field commander in Afghanistan, and finally as director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Nasr’s argument is that Petraeus, an outstanding West Point graduate who earned a doctoral degree at Princeton University, might have been a thinking man’s general, but he undervalued diplomacy. In Nasr’s experience, Petraeus regarded diplomacy merely “as a useful tool for getting governments around the world to contribute soldiers and money to the Afghan war. It was not a solution to the war, but its facilitator.”

Richard Holbrooke had negotiated an end to the Bosnian war and was one of the most experienced, forceful diplomats of his generation. He was restless, often distracted, and self- centered—certainly not everyone’s cup of tea—but he could equally be engaged, brilliant, curious, and unconventional, the rare diplomat who aspired to turn geopolitical tides by force of will. Petraeus, however, referred to Holbrooke as his “wingman,” a transparent bit of condescension Obama allowed to stand, apparently because Holbrooke’s self-dramatizing irritated him. Obama lacked the conviction either to back Holbrooke’s diplomacy or to fire him—another half-measure. Therefore, the Pentagon’s commanders and paramilitaries at the CIA took over Obama’s Afghan strategy and squeezed Holbrooke’s team, or forced them into subordinated roles. “This imbalance at the heart of American foreign policy was Obama’s to fix,” Nasr writes. But the president did not.

Nasr makes much of the fact that Petraeus and his allies in Obama’s war cabinet—who included, at times, Hillary Clinton, Holbrooke’s boss—refused to allow Holbrooke to open talks with the Taliban as early as 2009, when “the Taliban had been ready” to negotiate. Petraeus and his war fighters wanted to pummel the Taliban first, seek defectors from the guerrillas’ ranks, and then open strategic talks with the enemy from a position of military strength. Direct talks began only late in 2010, as Ahmed Rashid has earlier described in groundbreaking detail, but the initial discussions failed to gain traction and were later suspended by the Taliban.

Nasr’s view is that if talks had been started right away, they might well have reduced violence and pointed the way toward a durable political settlement. This is a counterfactual that can’t be disproved, but recent evidence does not support it. During 2012 and earlier this year, President Obama authorized an all-out effort to reopen a negotiating channel with the Taliban, but the Taliban’s fractious leadership has been unwilling to join in. For all of Holbrooke’s energy and skill, he may never have had a plausible negotiating partner in Mullah Mohammed Omar.

The best chapter in The Dispensable Nation is entitled “Who Lost Pakistan?,” which chronicles, step by step, the collapse of the US-Pakistani partnership between 2009 and the end of 2011. Holbrooke and Nasr believed that the surge into Afghanistan was misguided, Nasr writes, because the key to ending the Afghan war was not the defeat of the Taliban on the battlefield, but the change of “Pakistan’s strategic calculus.” Under this calculus, Pakistan covertly supported and sheltered the Taliban as an instrument of political influence in Afghanistan, partly to thwart India. Holbrooke and his team were thinking big:

If we wanted to change Pakistan, Holbrooke thought, we had to think in terms of a Marshall Plan. After a journalist asked him whether the $5 billion in aid was not too much for Pakistan, Holbrooke answered, “Pakistan needs $50 billion, not $5 billion.”

That might seem an outlandish amount, but the United States was spending $100 billion or so a year on its war in Afghanistan after 2009, to unclear strategic ends. Nasr’s case is that mustering funds to provide Pakistan, a nuclear-armed nation of 180 million, with energy, water, and finance to sustain economic growth and to support its urbanizing middle classes as they challenged the Pakistan army for political power was indeed a better bet than funding the US Marines to chase Taliban stragglers around the poppy-laced, dust-blown reaches of Helmand province.

To paraphrase the late Senator Everett Dirksen: a Marshall Plan here, a Marshall Plan there, and pretty soon you are talking about real money. Moreover, Pakistani nationalism is a fierce force; the country’s elites have long resisted, under many blandishments, American ideas about how they should define their strategic interests, whether in Afghanistan, toward India more generally, or in regard to their nuclear deterrent. Yet there can be no doubt that Holbrooke and Nasr were correct in their basic insights: Pakistan was critically important to American interests, and the country was changing and growing economically in subtle but positive ways that required American investment and patience. The intensified war next door in Afghanistan—particularly Obama’s heavy use of drones to strike Taliban and al-Qaeda targets inside Pakistan, which stirred anti-Americanism and made Pakistan’s government look feckless—undermined the long-term goals that Obama himself had defined for Pakistan.

On Iran, as Trita Parsi has also argued,3 Nasr believes the Obama administration gave up on diplomacy too soon and “succumbed to exaggerated Israeli and Arab fears” about Iran’s nuclear program. Like his argument for earlier talks with the Taliban, his case for more sustained and “rigorous” diplomacy is a counterfactual that cannot be disproved. Yet European and American negotiators have been arm-wrestling with Iranian counterparts for almost a decade now, with no grand bargain or even a sustainable détente in sight. More original and arresting is Nasr’s forecast of where the Obama administration’s current policy of covert action to attack Iranian nuclear facilities and ever-tighter economic sanctions will lead. It may “eventually turn Iran into a failed state,” Nasr fears. That is a prediction that deserves notice and debate.

The Dispensable Nation proceeds from the premise that the United States can still decisively influence fractious, violent, poor, crisis-ridden nations like Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, and Iran. Of course, the United States spends more on its military than most other nations combined, and its economy remains the world’s largest, even if China’s is on a trajectory to surpass it. Yet America’s experience in Iraq and Afghanistan reminded both American voters and the world’s nations about some of the limits of American hard power. The State Department’s indirect influence campaigns since September 11—to win Muslim cooperation, for instance—have faltered, too. In Nasr’s winkingly provocative formulation, the evidence of the last decade is that while the United States is not dispensable, neither is it indispensable; American power is in transition.

Yet Nasr sidesteps the arguments by foreign policy specialists such as Fareed Zakaria about how American influence may have changed or been diminished, at least in relative terms. There are important questions that he does not address: What are the implications for American strategy in the Middle East of the global recession, weak economic recovery, and heavy debt burdens faced by the United States and Europe? By what math can President Obama fund multiple Marshall Plans while also addressing America’s deficits in jobs, infrastructure, education, and middle-class incomes? In criticizing the administration, Nasr avoids an essential assumption of Obama’s foreign policy: that to revive global leadership in future decades, the United States must fix itself.

Nasr describes powerfully how American foreign policy has been militarized during the Bush and Obama administrations, and how diplomacy has too often been assigned a subordinate role as the civilian arm of expeditionary armies. Too many American ambassadors have spent too much time negotiating rights of way and logistics lines for the Pentagon during the past decade and not enough time on human rights, voter enfranchisement, disease eradication, and economic growth in the Middle East and elsewhere. Yet the ragged performances of the State Department and USAID in Iraq and Afghanistan cannot be explained only by the Pentagon’s overweening supremacy in those theaters.

The Gates Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, Google, Facebook, Apple, and (alas) even the Walt Disney Company have arguably projected more influence in the Middle East and Africa in recent years—including on the course of the Arab Spring—than the Department of State. These corporate and philanthropic actors have sometimes bigger budgets but also strategies that are better attuned to changes in technology, demography, and culture that are weakening states and empowering people and small groups worldwide. Nasr grades the Obama administration by the balance-of-power scorecards of international relations scholarship. Yet if the United States is to contribute to development, stability, and pluralism in developing societies, the next generation of foreign policy thinkers will have to reckon with the changing character of state power—and of American influence.

This Issue

July 11, 2013

A Pianist’s A–V

The Unbearable

-

1

Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (Penguin, 2012). ↩

-

2

See Bob Woodward, Obama’s Wars (Simon and Schuster, 2010), Rajiv Chandrasekaran, Little America (Knopf, 2012), and Ahmed Rashid, Pakistan on the Brink (Viking, 2012). ↩

-

3

See my “Will Iran Get That Bomb?,” The New York Review, May 24, 2012, which reviews in part Trita Parsi’s A Single Roll of the Dice: Obama’s Diplomacy with Iran (Yale University Press, 2012). ↩