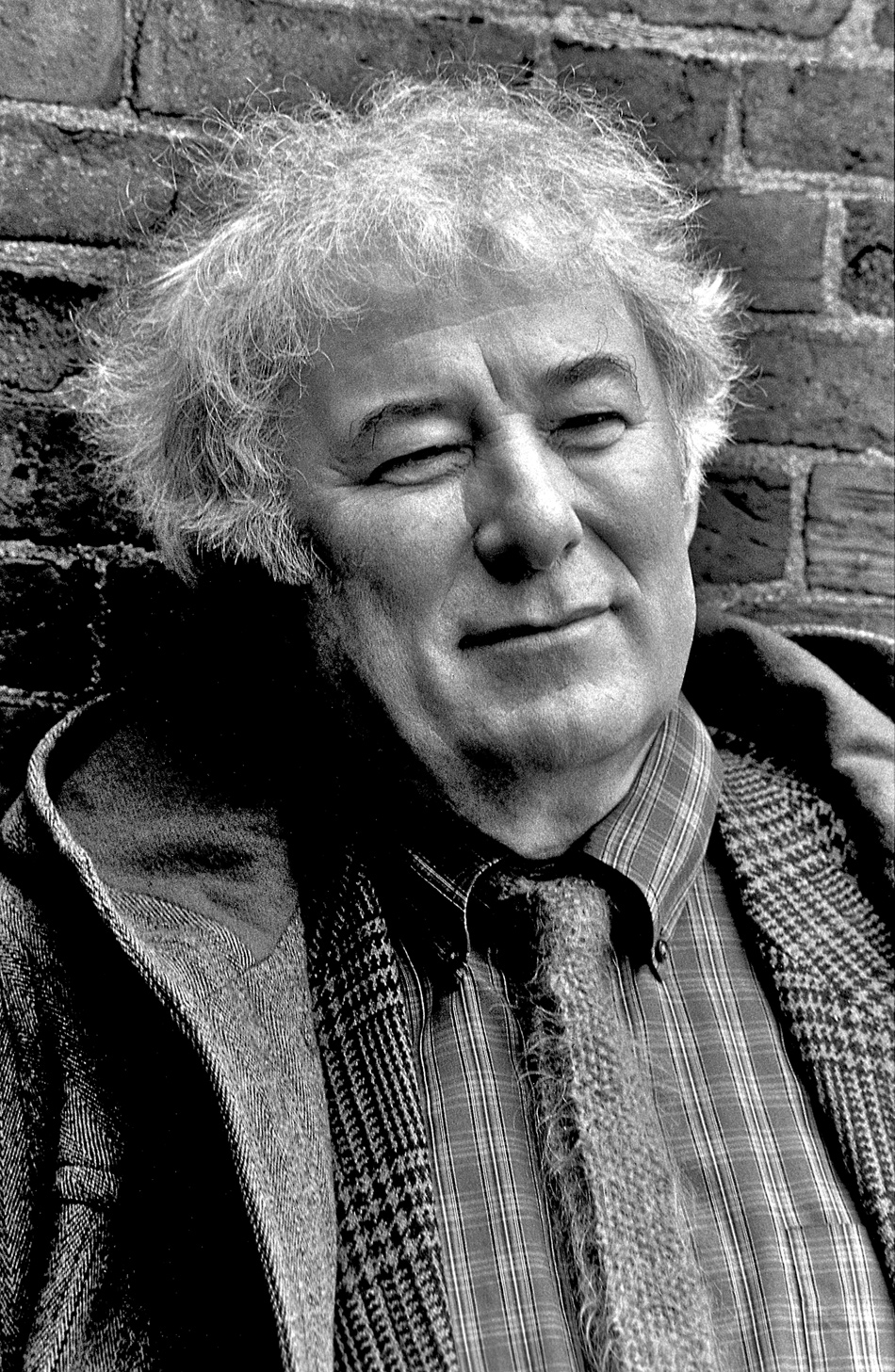

While the Nobel committee was looking for Seamus Heaney to tell him that he had won the 1995 prize for literature, he was driving through, of all places, Arcadia in southern Greece. This was doubly apt. Heaney was surely the English language’s last great Arcadian poet, the last whose memory cells contained personal images of a pastoral life, the last who could regard Virgil as a contemporary and write eclogues without irony. He was also, however, Arcadian in the other sense, the one depicted in those Poussin and Guercino paintings of idealized shepherds gazing at tombs or skulls inscribed with the words et in Arcadia ego: even in Arcadia, I (that is, death) am present.

In Heaney’s case, that shadowing presence was death indeed (he was, apart from so much else, a superb elegist), but also other potent disruptions: history, politics, culture. He made his work from the tension between the pull of an innocent rural world and the push of violence, complexity, conflict, and contradiction, the inescapable knowledge that there is no paradise that is not already lost.

He could evoke, with the precision of lived intimacy, an immemorial, pre-mechanical rural life:

My father worked with a horse-plough,

His shoulders globed like a full sail strung

Between the shafts and the furrow.

The horses strained at his clicking tongue.

(“Follower,” Death of a Naturalist)

But he could not escape

That old sense of a tragedy going on

Uncomprehended, at the very edge

Of the usual, it never left me once….

(“Known World,” Electric Light)

Urban readers may initially have been drawn to Heaney by some imagined promise of rustic nostalgia, but they stayed for the energy of a mind forever hovering between these contradictions. Poetry is language held taut by being stretched between the poles of competing desires. In Heaney’s work, the tensions extend in many directions: the Wordsworthian Romantic at odds with the Joycean realist; the atheist in search of the miraculous; the world-ranging cosmopolitan with his little patch of remembered earth; the lover of the archaic who cannot escape the urgency of contemporary history.

In one of his last public speeches, at the National Museum in Dublin last March, Heaney spoke of how “the objects on display range from the Mesolithic Age to the third millennium, and it surely says something about the Ireland I grew up in that I feel closer to the first exhibit from 7,000 years ago than I do to” those from the last years of the twentieth century. The childhood world of rural County Derry to which he returned again and again, the tiny universe of Mossbawn and Anahorish, of Toome and Lough Beg, was largely pre-industrial. Heaney could remember the blurry interiors before electric light and an exterior landscape that was as “sacramental, instinct with signs” as the land must have been to ancient man.

He could conjure up with startling vividness the motions of antiquated labors: farmers plowing with horses; threshers eating in the fields; thatchers making roofs with rushes; women making butter in wooden churns, their hands blistered, their arms aching; diviners magically dowsing for hidden underground water. If not quite Mesolithic, this world is certainly Brueghelesque:

They seem hundreds of years away. Brueghel,

You’ll know them if I can get them true.

(“Mossbawn 2, The Seed Cutters,” North)

Heaney’s poems are supercharged with the shock of the physical, of hard manual work, of tactile things. We talk of the poetic gaze, but in Heaney, it is not the poet’s eyes alone that count. It is also his hands. The era he inhabited in memory is “an age of bare hands/and cast iron.” He feels the weight of water-filled buckets in his palms, the heft of a trowel “So thick-spanned and daunting/I needed two hands,” or of a lump of raw beef “like dead weight in a sling.” He wields a sledgehammer and is thrilled by a blow “so unanswerably landed/The staked earth quailed and shivered in the handle.” He doesn’t just see eels or fish or frogs. He feels their slime. He imagines poetry itself as a well-wrought spade “Tastily finished and trim and right for the hand.” The stunning immediacy of his best poems comes from his ability to translate the abstract into the tactile. Love for him is

like a tinsmith’s scoop

sunk past its gleam

in the meal-bin.

(“Mossbawn 1, Sunlight,” North)

The world itself is an old implement:

The mass and majesty of this world I bring you

In the small compass of a cast-iron stove lid.

(“Home Fires,” District and Circle)

Other poets will, of course, feel the weight and texture of physical objects, but will any, at least in English, have grown to consciousness with such a potent sense of things that are handmade and worn with handling? Will any be so deeply marked by having been born into a way of life that had such strong continuities with an ancient past only to witness its rapid and final fading? For Heaney, the wonder of his childhood world lay not in its presence, but in its vanishing. As he wrote in his dazzling version of Rilke’s “After the Fire”:

Advertisement

For now that it was gone, it all seemed

Far stranger: more fantastical than Pharoah.

Not just gone, but never simple in the first place. There is no innocence in Heaney’s Arcadia. It is no accident that his first book is called not The Naturalist, but Death of a Naturalist, a fatality inflicted by the violent irruption of early sexuality, a biblical plague of frogs that bring with them an oozing physicality that is both repulsive and irresistible. The landscape itself, meanwhile, was overwritten by the politics and history of the cleavage between settler and native, Catholic and Protestant: “the lines of sectarian antagonism and affiliation followed the boundaries of the land.” That division was tragic, of course, and it haunted Heaney. But it also gave him his greatness.

It taught him the virtue of silence. The intimate antagonisms of Northern Ireland put a premium on verbal caution, what Heaney called, in “Whatever You Say Say Nothing,” “The famous/ Northern reticence, the tight gag of place/And times….” In one of his finest essays, Heaney mused on the phrase “the government of the tongue,” using it to explore the idea of poetry as an ideal realm. “All the same, as I warm to this theme, a voice from another part of me speaks in rebuke. ‘Govern your tongue,’ it says.”

Heaney’s tongue needed strong government, for he was, in conversation, a man of astonishing natural eloquence. The tight gag of place and times bounded that flow and compressed its energies. It found its aesthetic correlative in Heaney’s continual return to the traditional sonnet or the modified shortened sonnet. It was fruitful as well as restraining: Heaney’s Northern reticence made him distrust the trumpet-blast of full rhymes. He was forced to become the incomparable master of the half-rhyme, the off-rhyme, the teasing twist of aural and dissonance: plough/furrow; eye/exactly; crouch/hush; years/tractors; corncrake/iambic. Heaney turned the silence of fear into the care of art and the graceful tact of a public figure who managed, over thirty years of a bitter conflict, never to speak bitterly.

He also transformed conflict itself into the richness of diversity—not directly in the political sphere but in the field he himself plowed, the open terrain of language. He located himself very firmly within an Irish tradition, but embraced the English and Scottish ones too. Heaney was always in imaginative dialogue with Greek, Roman, Italian, American, and Polish poets. But his most deliberate acts of translation were from the Gaelic (the medieval Irish epic Sweeney Astray); the Scots (Robert Henryson’s The Testament of Cresseid & Seven Fables); and the Anglo-Saxon (Beowulf)—the three different traditions that defined the boundaries of his native landscape. And these were not just external gestures: he incorporated these different textures of sound into his own intimate memories. Take, for example, his recollection of plug tobacco from childhood: “Bog-bank brown, embossed, forbidden man-fruit.” Marvel at the delightful way those homely coupled words “bog-bank,” “man-fruit,” incorporate the clang of Beowulf into a tiny incident in a rural Irish childhood.

There is, in so many such moments, a historic generosity. The porousness of language, the refusal of words to know their places, eludes the control of narrow identities. The energy of that escape will power these poems into eternity. Long after their roots in a dying world and a nasty squabble are forgotten, they will “Move lips, move minds and make new meanings flare.”

For a selection of poems by Seamus Heaney from The New York Review’s archives, as well as essays about his work by Helen Vendler, James Fenton, and others, see the 50 Years blog, nybooks.test/50.