Professionally trained Dante scholars—I am one of them—believe we have special access to The Divine Comedy’s deeper layers of meaning, yet judged by Dante’s criteria, we are self-deceived. In Inferno 9, Dante challenges his audience with a direct address:

You readers, who are of sound mind and memory,

Pay attention to the lessons woven into the fabric

Of these strange poetic lines.

Who among the members of the Dante Society believes in good faith that he or she possesses the “sound mind” that Dante appeals to here? No one reconstructed the Christian doctrines that supposedly underlie the Comedy’s veils of allegory more piously than the great American Dante scholar Charles Singleton. Yet Singleton was an agnostic who took his own life, and one hopes for his sake that he was right when he declared, “The fiction of the Comedy is that it is not a fiction.” If the poem contains an arcane truth that is predicated on faith—not only in the medieval Christian God but also in Dante’s version of history, with its Holy Roman Emperors and all—then none of us will ever gain full access to it.

Fortunately the Comedy does not require such a passport for entry. Its reception over the centuries confirms that it gives itself without prejudice to “Presbyterians and Pagans alike,” to borrow a phrase from Herman Melville, himself a great Dante enthusiast. Despite a glut of English translations (well over a hundred, by my count), new versions of the entire poem or individual canticles continue to appear in rapid succession—six in the last decade alone.

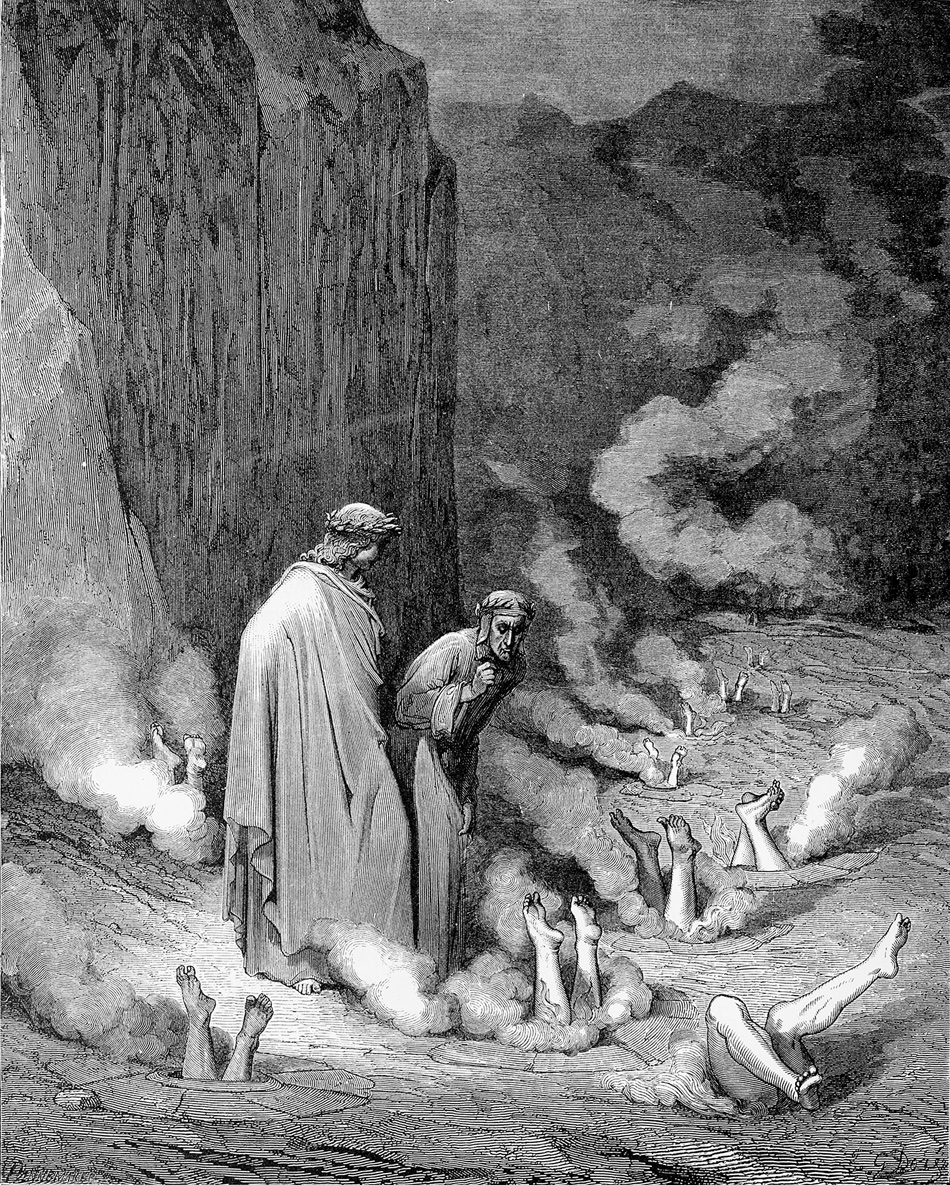

In 2004 the visual artist Sandow Birk illustrated a demotic version that sets the Comedy in contemporary American urban landscapes. In 2005 the Eternal Kool Project released a rap album called The Inferno Rap, based on Henry Francis Cary’s 1806 translation. Gary Panter’s 2006 punk-pop graphic novel Jimbo’s Inferno was followed in 2009 by the popular video game Dante’s Inferno. Roberto Benigni’s long-running comedy routine “Tutto Dante” continues to draw huge audiences, and, oblivious to it all, the industry of Dante studies churns out ever more scholarly articles, monographs, and academic conferences.

In Dan Brown’s new thriller, Inferno, Dante’s first canticle holds the clues to a global bioterrorist plot that threatens humanity. If nothing else, the novel lends evidence to what its protagonist, Professor Robert Langdon, declares in his lecture to the Dante Society in Vienna, namely that “no single work of writing, art, music, or literature has inspired more tributes, imitations, variations, and annotations than The Divine Comedy.” (Like everything else in this astonishingly bad novel, Langdon’s lecture lacks verisimilitude. Delivered in a great hall to over two thousand people who gasp, sigh, or murmur at every commonplace remark, it serves as a narrative ploy to convey rudimentary information about Dante to the uninformed reader.)

The mystery of The Divine Comedy has little to do with the encoded games of hide-and-seek that Brown plays with readers in his best-selling mystery thriller. It has to do instead with the poem’s staying power. How is it possible—after so many centuries of manhandling by commentators, translators, and imitators, after so much use and abuse, selling and soliciting—that the Comedy still has not finished saying what it has to say, giving what it has to give, or withholding what it has to withhold? What is the source of its boundless generosity?

It takes Charles Baudelaire to help us understand how a work of art can offer itself to everyone and belong finally to no one. “What is art?” he asks in one of the first notes of Mon coeur mis à nu. His answer: “prostitution,” by which he means indiscriminate giving of the self. The artwork’s prostitution is “sacred,” not profane, for it offers itself freely. Thus art has an essential bond with love, which shares with art the “need to go outside of oneself.” “All love is prostitution,” writes Baudelaire. In that respect both art and love partake of the self-surpassing generosity through which God gives himself to the world: “The most prostituted being of all, the being par excellence, is God, since he is the supreme friend of every individual, since he is the common, inexhaustible reservoir of love.”

One reason why The Divine Comedy remains the most generous work in literary history is because it brings together these three phenomena—God, love, and art—in a first-person story where they flow into and out of one another promiscuously, such that it is impossible finally to distinguish between the Comedy’s art and “the love that moves the sun and the other stars.” Even if one knows nothing about the Christian theology that structures the poem, the love that keeps it moving sweeps the reader up along with it.

Advertisement

In its architectural weight and grandeur The Divine Comedy appears to modern readers as a great Gothic cathedral made of solid verse. One has a sense that, a thousand years from now, its nine circles of Hell and nine heavenly spheres will still be there, while our diminutive modern society, with its fleeting concerns and anxieties, will have long disappeared. Yet strange as it may seem, this monumental poem has one overriding, all-consuming vocation, namely to probe, understand, and represent the nature of motion in its spiritual and cosmic manifestations.

The opening of Inferno finds the pilgrim lost in a dark wood. We may debate the nature of this midlife crisis, or exactly what the wood represents in the poem’s allegory, yet one thing we know for sure is that Dante’s predicament takes the form of an impasse. The way is blocked. Until Virgil arrives on the scene, he is unable to move forward. The rest of the poem unfolds the long and circuitous process by which Dante is rescued from his immobilization.

To find oneself at a dead end in the midst of life—to discover suddenly that all ways of moving are closed off—is equivalent to a kind of death (“death is hardly more bitter,” Dante declares). Anyone who has experienced even mild forms of depression knows what the state of paralysis in Inferno 1 is all about. Depression brings things to an oppressive standstill; its objective correlative is a dark room and a bed, which can easily take on the feel of an alien forest. Of all the English translations known to me, Mary Jo Bang provides the most vivid, albeit not the most literal, version of the poem’s opening tercet:

Stopped mid-motion in the middle

Of what we call our life, I looked up and saw no sky—

Only a dense cage of leaf, tree, and twig. I was lost.

If one is going to take liberties with the original, as both of the translations under review do, there should be a payoff. Here the payoff is a highly dynamic phrasing, with imagery and rhythms that intensify the sense of entrapment and disorientation. The first line retrieves the alliterations of m of Dante’s original (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita,/mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,/ché la diritta via era smarrita). The subsequent alliterations of l give emphatic weight to the word “lost.” The heavy successive stresses on the first three syllables—“stopped mid-motion”—drive home the blockage under description. Suspending the first line after the word “middle”—in the very middle of the phrase—works magic as prosody. In the second line Bang finds an effective way to preserve Dante’s crucial conjoining of “our life” and the first-person singular (nostra vita/mi ritrovai).

Clive James gives us a much less dramatic version:

At the mid-point of the path through life, I found

Myself lost in a wood so dark, the way

Ahead was blotted out….

James omits the all-important pronoun “our,” and his smooth cadence does not suit the emotion of panic nearly as well as Bang’s staccato version. The only reason James tacks on “I found” to the first line, and then tacks on “the way” to the second, is for the sake of a rhyme (James decided to cast his translation in quatrains, and to rhyme them abab). James’s version continues:

The keening sound

I still make shows how hard it is to say

How harsh and bitter that place felt to me—

To interpolate a “keening sound” here is ludicrous, for at the start of the poem Dante has just returned from the luminous realm of Christian beatitude, so he would not “still” be wailing or shrieking with grief. The distortion seems a high price to pay for the sake of a rhyme.

The Divine Comedy is all about overcoming the paralysis that afflicts the pilgrim at the beginning of Inferno 1. His therapy takes the form of a journey that begins with the remarkable last line of that canto, where Dante, following his guide Virgil, sets out on his descent through Hell. The Italian states: “Allor si mosse, e io li tenni dietro.” Literally rendered: “Then he [Virgil] moved, and I followed behind him.” James fails to convey the filial piety contained in this image of Dante following the Roman poet: “And then he moved, and then I moved as well.” Mary Jo Bang, by contrast, gets it exactly right: “Then he set out, and I at his back.”

What did Dante learn from Virgil that made him eager to follow in his footsteps? He learned what it means to write a poem whose narrative not only moves but has movement as its prime directive. After the fall of Troy, Aeneas mobilizes the Trojan refugees and leads them across the Mediterranean, by way of Carthage, to a new land, where the Trojan legacy, by providential decree, will one day be reborn in the city of Rome. In Virgil’s Aeneid Aeneas is, like his people, weary, full of sorrows, and prone to depression, yet he is compelled by the gods to continue the journey until he arrives at the mouth of the Tiber River. On several occasions the Trojans are tempted to put down their oars and settle down, yet the gods keep them on the go until they arrive at their appointed destination.

Advertisement

Like The Aeneid, The Divine Comedy propels both the journey and the poem forward through multiple mechanisms, including its highly dynamic rhyme scheme of interlocking tercets (terza rima, as it’s known in Italian), as well as its narrative drama. Mary Jo Bang preserves the tercet form without attempting to reproduce Dante’s rhyme scheme. Being an excellent poet in her own right, she succeeds in giving the Inferno’s narrative drama an energetic idiom that gets the poem moving, and at times even dancing, on the page.

Since Bang aims for a resolutely contemporary translation of the Inferno, she often employs devices that will cause squeamish scholars and purists to gasp. She frequently echoes literary works that postdate the Comedy by centuries (for example in Canto IV: “Let us go, then, you and I….”); she incorporates myriad references to pop music and contemporary culture (Canto VIII: “An Ultimate Aero couldn’t pass through air any faster/than the little skiff”); and she does not shy away from anachronistic images (in Inferno 27 she refers to the “strobe-light motion” that Guido da Montefeltro’s flame makes when his soul speaks to Dante through its flickering tip). She commits several unforced errors along the way, to be sure, yet she hits many more winners in the overall count. The result is one of the most readable and enjoyable versions of the Inferno of our time. I stress “our time” because, as Bang herself acknowledges, her translation is “destined to become an artifact of its era,” while “the original poem will continue to exist.”

Clive James’s translation has no such élan. His decision to dispense with explanatory notes altogether and to lift the relevant information “out of the basement and put…it on display in the text” comes at a high price with minimal payoff, not only because it obliges him to import into the body of the poem much material that does not properly belong there, but because it invariably blunts the narrative impact of the original. In theory James understands that The Divine Comedy is all about movement (“Dante has a thousand tricks…to keep things moving”), yet in practice his translation tends to obstruct what he calls the “mutually reinforcing balance of tempo and texture.”

In his introduction, James tells us that the seed of his translation of The Divine Comedy was planted in the 1960s when his wife, the distinguished Dante scholar Prue Shaw, drew his attention to the exquisite micropoetics of Inferno 5, “where syllables met each other and generated force.” Here is how James translates the latter portion of Francesca’s famous speech in the circle of lust, where she describes for Dante how she and her brother-in-law Paolo fell into the sin of adultery:

Reading together one day for delight

Of Lancelot, caught up in love’s sweet snare,

We were alone, with no thought of what might

Occur to us, although we stopped to stare

Sometimes at what we read, and even paled.

But then the moment came we turned a page

And all our powers of resistance failed:

When we read of that great knight in a rage

To kiss the smile he so desired, Paolo,

This one so quiet now, made my mouth still—

Which, loosened by those words, had trembled so—

With his mouth. And right then we lost the will—

For love can will will’s loss, as well you know—

To read on. But let that man take a bow

Who wrote the book we called our Galahad,

The reason nothing can divide us now.

James’s translation of The Divine Comedy contains some fine moments, yet this surely is not one of them. One way to gauge the degree to which it bogs down and convolutes the seductive charm of Francesca’s account with awkward phrasing and altogether gratuitous editorializing interpolations is to compare it to Mary Jo Bang’s rendition:

One day, to amuse ourselves, we were reading

The tales of love-struck Lancelot; we were all alone,

And naively unaware of what could happen.More than once, while reading, we looked up

And saw the other looking back. We’d blush, then pale,

Then look down again. Until a moment did us in.We were reading about the longed-for kiss

The great lover gives his Guinevere, when that one

From whom I’ll now never be parted,Trembling, kissed my lips.

That author and his book played the part

Of Gallehault. We read no more that day.

Francesca is the prototype of Emma Bovary, who in her youth devoured the popular romance fiction of her time and modeled her behavior on its female exemplars. Here and earlier in her speech Francesca reveals that she had been a devotee of the amorous poetry and chivalric love stories of her era. In Inferno 5 Dante gives her exactly what she desired most in life, whether she was aware of it or not: to become a great heroine of literature.

With the exception of the souls in Limbo, who are guiltless, all of Dante’s sinners have, like Francesca, followed their bliss into Hell. Despite their wails and lamentations, they are exactly where they want to be, for in Dante’s universe, salvation or damnation depends entirely on the individual’s free will. All the sins punished in Hell proper are opted for by the will of those who enacted them. Unlike his predecessors, who envisioned Hell as a chaotic torture gallery, Dante took great care to devise punishments that reveal in symbolic form what the inner will desires when it commits the corresponding sins (the lustful desire the storm of passion in which they are swept up in Inferno 5; the violent desire the river of blood in which they are immersed, etc.). As the agency of human motivation, the will moves the soul one way or another—either away from God or toward God.

Despite the heavy price the damned pay for their past acts, never do we encounter a penitent soul among their throng. On the contrary, most of the major characters in Dante’s Inferno reenact for the pilgrim—and hence for us—the choices that landed them in Hell in the first place. Francesca repeats in her speech the errors, self-delusions, and romantic mystifications that drew her into her adulterous affair with Paolo. Her self-exculpations and displacement of blame only serve to reindict her. Likewise Farinata is as prideful and partisan as ever in the circle of the heretics. In his ambiguous and duplicitous speech in Inferno 27, Guido da Montefeltro rehearses for Dante the willful self-deception that got him damned. Ulysses restages for us in speech the heroic but tragic hubris that brought on disaster for him and his men.

By reembracing their sins before our eyes (or ears), the sinners track in their soliloquies the psychological or moral motions of the will that led them to their present fates. The pilgrim seizes upon his encounters with these sinners to confront within himself his own wayward dispositions.

Much of the fascination of the Inferno revolves around Dante’s probing of the covert psychic recesses of his characters’ inner will. The sinners’ great soliloquies are self-serving and fraught with irony. One cannot take them at their word. One must bring to bear on their speeches a “hermeneutics of suspicion” that is alert to the discrepancy between what they tell us and what they show us. Oftentimes the characters themselves are unaware of the way they are masking their true motivations, which makes it all the more imperative that the reader adopt an analytic distance from their self-presentations. In sum, the Inferno educates the reader in the ways of deception and self-deception, and in that respect remains one of the great archives of human psychology.

This is one lesson that Dan Brown, for all his admiration of Dante, did not learn from the Inferno. Brown’s Inferno shares in common with its namesake the generic imperative of moving the story along, of keeping it projected toward a conclusive outcome, yet this is where the affinities end. An abyss separates the monodimensional crudeness of Brown’s narrative devices from the multidimensional complexity of Dante’s. Brown’s novel has a cast of characters, to be sure, yet it has no interest in tracking the inner motions of their souls or probing the muddled sources of their motivation. His characters are so thoroughly vapid and cartoonish that one suspects that Brown deliberately refrained from giving them any psychological density for fear that this would merely create friction on the high-speed rails on which his thriller races along. The good news, for readers who go along for the ride, is that the novel reaches its destination quickly.

In her last words to Professor Robert Langdon before she boards a C-130 plane in Turkey, Sienna, the main female character in Brown’s Inferno, attempts to say something meaningful. “‘Thank you, Robert,’ she said, as the tears began to flow. ‘I finally feel like I have a purpose.’” Does this mean that Sienna is moving from an infernal to a purgatorial state of being (she is, after all, about to ascend)? Nothing in the book encourages such a speculation, yet we should note nonetheless that the big difference between the sinners in Dante’s Hell and the penitents in his Purgatory is that the former are going nowhere, while the latter are moving toward a goal, namely the purgation of their sins and their eventual assumption into Paradise. In Purgatory time matters, and motion has a purpose. In Hell, by contrast, no matter how much the souls may be buffeted by storms, or run on burning sands, or carry heavy burdens, motion leads nowhere. In Dante’s vision Hell is a never-ending waste of time.

The great metaphysical doctrine underlying The Divine Comedy is that time is engendered by motion. Like the medieval scholastic tradition in which he was steeped, Dante subscribed to Plato’s notion that time, in its cosmological determinations, is “a moving image of eternity.” He subscribed furthermore to the Platonic and Aristotelian notion that the truest image of eternity in the material world is the circular motions of the heavens. Thus in Dante’s Paradiso, the heavenly spheres revolve in perfect circles around the “unmoved Mover,” namely God.

In the final analysis there are two kinds of motion in the world for Dante: the predetermined orderly motion of the cosmos, which revolves around the Godhead, and the undetermined motion of the human will, which is free to choose where to direct its desire—either toward the self or toward God. Yet be it self-love or love of God (love of neighbor is a declension of the latter), what moves the heavens is the same force that moves both sinners and saints alike, namely amor.

The basic “plot” of The Divine Comedy has to do with the pilgrim’s efforts to complete a long, self-interrogating, and transformative journey at the end of which his inner being—which, like human history, suffers from the perversion of self-love—becomes harmonized with the love that moves the universe. Salvation means nothing more, and nothing less, than such harmonization. It is not until the very last lines of Paradiso that the Comedy’s story reaches its conclusion. In those lines we read that, thanks to a special act of grace, the pilgrim’s inner self turns like a wheel:

ma già volgeva il mio disio e ’l velle,

sì come rota ch’igualmente è mossa,

l’amor che move il sole e le altre stelle.

Clive James, who is at his best in Paradiso, gives a particularly good translation of these verses, despite his compulsion to editorialize them, as he does with much of the rest of Dante’s poem:

…but now, just like a wheel

That spins so evenly it measures time

By space, the deepest wish that I could feel

And all my will, were turning with the love

That moves the sun and all the stars above.

This final integration of the pilgrim’s will with the turning motion of the universe represents a dramatic conclusion to a dramatic poem—a conclusion that takes on its full scope of meaning only after the reader has undertaken the effort to accompany Dante on his laborious journey from its very inception in the dark wood of Inferno 1. “In my beginning is my end,” wrote T.S. Eliot at the beginning of “East Coker,” which ends with that statement’s inversion: “In my end is my beginning.” So it is with the Comedy. Or as Beatrice puts it when she descends into Limbo to enlist Virgil to rescue Dante from his impasse in the dark wood: “Amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare,” “love has moved me, and makes me speak.”