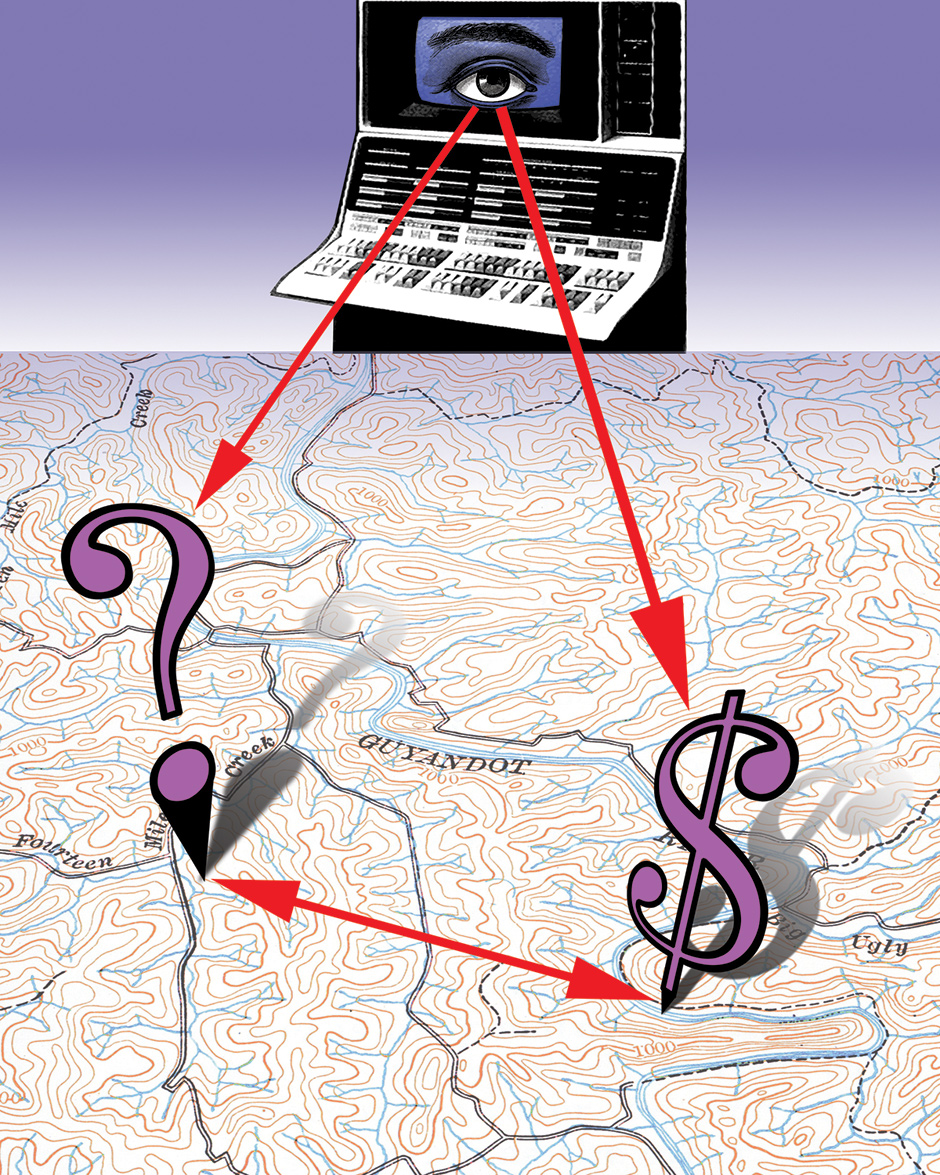

Early this year, as part of the $92 million “Data to Decisions” program run by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Office of Naval Research began evaluating computer programs designed to sift through masses of information stored, traded, and trafficked over the Internet that, when put together, might predict social unrest, terrorist attacks, and other events of interest to the military. Blog posts, e-mail, Twitter feeds, weather reports, agricultural trends, photos, economic data, news reports, demographics—each might be a piece of an emergent portrait if only there existed a suitable, algorithmic way to connect them.

DARPA, of course, is where the Internet was created, back in the late 1960s, back when it was called ARPA and the new technology that allowed packets of information to be sent from one computer to another was called the ARPANET. In 1967, when the ARPANET was first conceived, computers were big, expensive, slow (by today’s standards), and resided primarily in universities and research institutions; neither Moore’s law—that processing power doubles every two years—nor the microprocessor, which was just being developed, had yet delivered personal computers to home, school, and office desktops.

Two decades later, a young British computer scientist at the European Organization for Nuclear Research named Tim Berners-Lee was looking for a way to enable CERN scientists scattered all over the world to share and link documents. When he conceived of the World Wide Web in 1988, about 86 million households had personal computers, though only a small percentage were online. Built on the open architecture of the ARPANET, which allowed discrete networks to communicate with one another, the World Wide Web soon became a way for others outside of CERN, and outside of academia altogether, to share information, making the Web bigger and more intricate with an ever-increasing number of nodes and links. By 1994, when the World Wide Web had grown to ten million users, “traffic was equivalent to shipping the entire collected works of Shakespeare every second.”

1994 was a seminal year in the life of the Internet. In a sense, it’s the year the Internet came alive, animated by the widespread adoption of the first graphical browser, Mosaic. Before the advent of Mosaic—and later Internet Explorer, Safari, Firefox, and Chrome, to name a few—information shared on the Internet was delivered in lines of visually dull, undistinguished, essentially static text. Mosaic made all those lines of text more accessible, adding integrated graphics and clickable links, opening up the Internet to the average, non-geeky user, not simply as an observer but as an active, creative participant. “Mosaic’s charming appearance encourages users to load their own documents onto the Net, including color photos, sound bites, video clips, and hypertext ‘links’ to other documents,” Gary Wolfe wrote in Wired that year.

By following the links—click, and the linked document appears—you can travel through the online world along paths of whim and intuition…. In the 18 months since it was released, Mosaic has incited a rush of excitement and commercial energy unprecedented in the history of the Net.

In 1994, when Wolfe extolled the commercial energy of the Internet, it was still largely devoid of commerce. To be sure, the big Internet service providers like America Online (AOL) and CompuServe were able to capitalize on what was quickly becoming a voracious desire to get connected, but for the most part, that is where business began and ended. Because few companies had yet figured out how to make money online—Amazon, which got in early, in 1995, didn’t make a profit for six years—the Internet was often seen as a playground suitable for youthful cavorting, not a place for serious grownups, especially not serious grownups with business aspirations. “The growth of the Internet will slow drastically [as it] becomes apparent [that] most people have nothing to say to each other,” the economist Paul Krugman wrote in 1998. “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s…. Ten years from now the phrase information economy will sound silly.”

Here Krugman was dead wrong. In the first five years of the new millennium, Internet use grew 160 percent; by 2005 there were nearly a billion people on the Internet. By 2005, too, the Internet auction site eBay was up and running, Amazon was in the black, business-to-business e-commerce accounted for $1.5 trillion, while online consumer purchases were estimated to be between $142 and $772 billion and the average Internet shopper was looking more and more like the average shopper.

Meanwhile, entire libraries were digitized and made available to all comers; music was shared, not always legally; videos were made, many by amateurs, and uploaded to an upstart site (launched in 2005) called YouTube; the online, open-source encyclopedia Wikipedia had already begun to harness collective knowledge; medical researchers had used the Internet for randomized, controlled clinical trials; and people did seem to have a lot to say to each other—or at least had a lot to say. There were 14.5 million blogs in July 2005 with 1.3 billion links, double the number from March of that year. The social networking site Facebook, which came online in 2004 for Ivy Leaguers, was opened to anyone over thirteen in 2006. It now has 850 million members and is worth approximately $80 billion.

Advertisement

The odd thing about writing even a cursory reprise of the events attendant to the birth of the Internet is that those events are so recent that most of us have lived through and with them. While familiar—who doesn’t remember their first PC? who can forget the fuzzy hiss and chime of the dial-up modem?—they are also new enough that we can remember a time before global online connectivity was ubiquitous, a time before the stunning flurry of creativity and ingenuity the Internet unleashed. Though we know better, we seem to think that the Internet arrived, quite literally, deus ex machina, and that it is, from here on out, both a permanent feature of civilization and a defining feature of human advancement.

By now, the presence and reach of the Internet is felt in ways unimaginable twenty-five or ten or even five years ago: in education with “massive open online courses,” in publishing with electronic books, in journalism with the migration from print to digital, in medicine with electronic record-keeping, in political organizing and political protest, in transportation, in music, in real estate, in the dissemination of ideas, in pornography, in romance, in friendship, in criticism, in much else as well, with consequences beyond calculation. When, in 2006, Merriam-Webster declared “google” to be a verb, it was a clear declaration of the penetration of the Internet into everyday life.

Nine years before, in the brief history of the Internet written by Vint Cerf and other Internet pioneers, the authors explained that the Internet “started as the creation of a small band of dedicated researchers, and has grown to be a commercial success with billions of dollars of annual investment.” Google—where Cerf is now “Chief Internet Evangelist”—did not yet exist. Its search engine, launched in 1998, changed everything that has to do with the collecting and propagating of information, and a lot more as well.

Perhaps most radically, it changed what was valuable about information. No longer was the answer to a query solely what was prized; value was now inherent in the search itself, no matter the answer. Google searches, however benign, allowed advertisers and marketers to tailor their efforts: if you sought information on Hawaiian atolls, for example, you’d likely see ads for Hawaiian vacations. (If you search today for backpacks and pressure cookers, you might see an agent from the FBI at your front door.) Though it was not obvious in those early years, the line from commerce to surveillance turned out to be short and straight.

Also not obvious was how the Web would evolve, though its open architecture virtually assured that it would. The original Web, the Web of static homepages, documents laden with “hot links,” and electronic storefronts, segued into Web 2.0, which, by providing the means for people without technical knowledge to easily share information, recast the Internet as a global social forum with sites like Facebook, Twitter, FourSquare, and Instagram.

Once that happened, people began to make aspects of their private lives public, letting others know, for example, when they were shopping at H+M and dining at Olive Garden, letting others know what they thought of the selection at that particular branch of H+M and the waitstaff at that Olive Garden, then modeling their new jeans for all to see and sharing pictures of their antipasti and lobster ravioli—to say nothing of sharing pictures of their girlfriends, babies, and drunken classmates, or chronicling life as a high-paid escort, or worrying about skin lesions or seeking a cure for insomnia or rating professors, and on and on.

The social Web celebrated, rewarded, routinized, and normalized this kind of living out loud, all the while anesthetizing many of its participants. Although they likely knew that these disclosures were funding the new information economy, they didn’t especially care. As John Naughton points out in his sleek history From Gutenberg to Zuckerberg: What You Really Need to Know About the Internet:

Everything you do in cyberspace leaves a trail, including the “clickstream” that represents the list of websites you have visited, and anyone who has access to that trail will get to know an awful lot about you. They’ll have a pretty good idea, for example, of who your friends are, what your interests are (including your political views if you express them through online activity), what you like doing online, what you download, read, buy and sell.

In other words, you are not only what you eat, you are what you are thinking about eating, and where you’ve eaten, and what you think about what you ate, and who you ate it with, and what you did after dinner and before dinner and if you’ll go back to that restaurant or use that recipe again and if you are dieting and considering buying a Wi-Fi bathroom scale or getting bariatric surgery—and you are all these things not only to yourself but to any number of other people, including neighbors, colleagues, friends, marketers, and National Security Agency contractors, to name just a few. According to the Oxford professor Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier, the “data editor” of The Economist, in their recent book Big Data:

Advertisement

Google processes more than 24 petabytes of data per day, a volume that is thousands of times the quantity of all printed material in the US library of Congress…. Facebook members click a “like” button or leave a comment nearly three billion times per day, creating a digital trail that the company can mine to learn about users’ preferences.

How all this sharing adds up, in dollars, is incalculable because the social Web is very much alive, and we keep supplying more and more personal information and each bit compounds the others. Eric Siegel in his book Predictive Analytics notes that “a user’s data can be purchased for about half a cent, but the average user’s value to the Internet advertising ecosystem is estimated at $1,200 per year.” Just how this translates to the bottom line is in many cases unclear, though the networking company Cisco recently projected that the Internet will be worth $14.1 trillion by 2022.

For the moment, however, the crucial monetary driver is not what the Internet will be worth, it’s the spread between what it costs to buy personal information (not much) and how much can be made from it. When Wall Street puts a value on Facebook or Google and other masters of the online universe, it is not for the services they provide, but for the data they collect and its worth to advertisers, among others. For these Internet companies, the convenience of sending e-mail, or posting high school reunion pictures, or finding an out-of-the-way tamale stand near Reno is merely bait to lure users into offering up the intimacies of their lives, often without realizing how or where or that those intimacies travel.

An investigation by The Wall Street Journal found that “50 of the most popular websites (representing 40 percent of all web pages viewed by Americans) placed a total of 3,180 tracking devices on the Journal’s test computer…. Most of these devices were unknown to the user.” Facebook’s proposed new privacy policy gives it “permission to use your name, profile picture, content, and information in connection with commercial, sponsored or related content…served or enhanced by [the company].” In other words, Facebook can use a picture of you or your friends to shill for one of its clients without asking you. (While those rules were pending, Facebook was forced to apologize to the parents of a teenager who had killed herself after being bullied online when the dead young woman’s image showed up in a Facebook ad for a dating service.)

It is ironic, of course, and deeply cynical of Facebook to call signing away the right to control one’s own image a matter of a “privacy policy,” but privacy in the Internet Age is challenged not only by the publicness encouraged by Internet services but by the cultures that have adopted them. As Alice Marwick, a keen ethnographer of Silicon Valley, points out in her new book Status Update, “social media has brought the attention economy into the everyday lives and relationships of millions of people worldwide, and popularized attention-getting techniques like self-branding and lifestreaming.”

People choose to use a service like Facebook despite its invasive policies, or Google, knowing that Google’s e-mail service, Gmail, scans private communications for certain keywords that are then parlayed into ads. People choose to make themselves into “micro-celebrities” by broadcasting over Twitter. People choose to carry mobile phones, even though the phones’ geolocation feature makes them prime tracking devices. How prime was recently made clear when it was reported in Der Spiegel that “it is possible for the NSA to tap most sensitive data held on these smart phones, including contact lists, SMS traffic, notes and location information about where a user has been.” But forget about the NSA—the GAP knows we’re in the neighborhood and it’s offering 20 percent off on cashmere sweaters!

Even if we did not know the extent of the NSA’s reach into our digital lives until recently, the Patriot Act has been in place since 2001 and it is no secret that it allows the government access to essentially all online activity, while online activity has grown exponentially since 2001. Privacy controls exist, to be sure, but they require users to “opt-in,” which relatively few are willing to do, and may offer limited security at best. According to researchers at Stanford, half of all Internet advertising companies continued tracking even when tracking controls had been activated. Anonymity offers little or no shield, either. Recently, Latanya Sweeney and her colleagues at Harvard showed how simple it was to “reidentify” anonymous participants in the Human Genome Project: using information about medicines, medical procedures, date of birth, gender, and zip code, she writes, and “linking demographics to public records such as voter lists, and mining for names hidden in attached documents, we correctly identified 84 to 97 percent of the profiles for which we provided names.”

Anonymity, of course, is not necessarily a virtue; on the Internet it is often the refuge for “trolls” and bullies. But transparency brings its own set of problems to the Internet as well. When a group of clever programmers launched a website called Eightmaps that showed the names and addresses of anyone who had donated over $100 to the campaign to prohibit same-sex marriage in California, the donors (and their employers, most famously the University of California) began getting harassing e-mails and phone calls. To those who support same-sex marriage this may seem just deserts, but the precedent has been set, whatever one’s political preferences, and next time the targets may be those who support marriage equality or gun control or abortion.

It’s not that donor information has not been public before, it’s that the broad reach and accessibility allowed by the Internet can have an amplifying effect. (On the other hand, it’s this amplifying effect that campaigners count on when seeking signatures for online petitions and organizing demonstrations.) Evgeny Morozov, the author of The Net Delusion and the new To Save Everything, Click Here, is no fan of transparency, and points out another pitfall. Everyone else’s prodigious sharing may shine an uncomfortably bright light on those who choose not to share: What might an insurer infer if, say, many others are posting personal health data about weight and blood pressure and exercise routines and you aren’t? This kind of transparency, he observes, favors the well and well-off “because self-monitoring will only make things better for you. If you are none of those things, the personal prospectus could make your life much more difficult, with higher insurance premiums, fewer discounts, and limited employment prospects.”

Closely monitoring and publicly sharing one’s health information is part of a growing trend of “the quantified self” movement, whose motto is “self-knowledge through numbers.” While not itself created by the Internet, it is a consequence of Internet culture, augmented by wireless technology, Web and mobile apps, and a belief that the examined life is one that’s sliced, diced, and made from data points. If recording blood pressure, heart rate, food consumption, and hours of sleep does not yield sufficient self-knowledge, advocates of “the quantified self” can also download the Poop Diary app “to easily record your every bowel movement—including time, color, amount, and shape information.” While this may seem extreme now, it is unlikely to seem so for long. We are living, we are told, in the age of Big Data and it will, according to Mayer-Schönberger and Cukier (and Wall Street and DARPA and many others), “transform how we live, work, and think.”

Internet activities like online banking, social media, web browsing, shopping, e-mailing, and music and movie streaming generate tremendous amounts of data, while the Internet itself, through digitization and cloud computing, enables the storage and manipulation of complex and extensive data sets. Data—especially personal data of the kind shared on Facebook and the kind sold by the state of Florida, harvested from its Department of Motor Vehicles records, and the kind generated by online retailers and credit card companies—is sometimes referred to as “the new oil,” not because its value derives from extraction, which it does, but because it promises to be both lucrative and economically transformative.

In a report issued in 2011, the World Economic Forum called for personal data to be considered “a new asset class,” declaring that it is “a new type of raw material that’s on par with capital and labour.” Morozov quotes an executive from Bain and Company, which coauthored the Davos study, explaining that “we are trying to shift the focus from purely privacy to what we call property rights.” It’s not much of a stretch to imagine who stands to gain from such “rights.”

Individually, data points are typically small and inconsequential, which is why, day to day, most people are content to give them up without much thought. They only come alive in aggregate and in combination and in ways that might never occur to their “owner.” For instance, records of music downloads and magazine subscriptions might allow financial institutions to infer race and deny a mortgage. Or search terms plus book and pharmacy purchases can be used to infer a pregnancy, as the big-box store Target has done in the past.

As Steve Lohr has written in The New York Times about the MIT economist Erik Brynjolfsson, “data measurement is the modern equivalent of the microscope.” Sean Gourley, cofounder of a company called Quid, calls this new kind of data analysis a “macroscope.” (Quid “collect[s] open source intelligence through thousands of different information channels [and takes] this data and structure[s] it to extract entities and events that we can then use to build models that help humans understand the complexity of the world around us.”) The very accurate Google Flu Trends, which sorts and aggregates Internet search terms related to influenza to track the spread of flu across the globe, is an example of finding a significant pattern in disparate and enormous amounts of data—data that did not exist before the Internet.

Computers are often compared to the human brain, but in the case of data collection and data mining, the human brain is woefully underpowered. Watson, the IBM computer used by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center to diagnose cancer—which it did more precisely than any doctor—was fed about 600,000 pieces of medical evidence, more than two million pages from medical journals, and had access to about 1.5 million patient records, which was its crucial advantage.

This brings us back to DARPA and its quest for an algorithm that will sift through all manner of seemingly disconnected Internet data to smoke out future political unrest and acts of terror. Diagnosis is one thing, correlation something else, prediction yet another order of magnitude, and for better and worse, this is where we are taking the Internet. Police departments around the United States are using Google maps, together with crime statistics and social media, to determine where to patrol, and half of all states use some kind of predictive data analysis when making parole decisions. More than that, gush the authors of Big Data:

In the future—and sooner than we may think—many aspects of our world will be augmented or replaced by computer systems that today are the sole purview of human judgment…perhaps even identifying “criminals” before one actually commits a crime.

The assumption that decisions made by machines that have assessed reams of real-world information are more accurate than those made by people, with their foibles and prejudices, may be correct generally and wrong in the particular; and for those unfortunate souls who might never commit another crime even if the algorithm says they will, there is little recourse. In any case, computers are not “neutral”; algorithms reflect the biases of their creators, which is to say that prediction cedes an awful lot of power to the algorithm creators, who are human after all. Some of the time, too, proprietary algorithms, like the ones used by Google and Twitter and Facebook, are intentionally biased to produce results that benefit the company, not the user, and some of the time algorithms can be gamed. (There is an entire industry devoted to “optimizing” Google searches, for example.)

But the real bias inherent in algorithms is that they are, by nature, reductive. They are intended to sift through complicated, seemingly discrete information and make some sort of sense of it, which is the definition of reductive. But it goes further: the infiltration of algorithms into everyday life has brought us to a place where metrics tend to rule. This is true for education, medicine, finance, retailing, employment, and the creative arts. There are websites that will analyze new songs to determine if they have the right stuff to be hits, the right stuff being the kinds of riffs and bridges found in previous hit songs.

Amazon, which collects information on what readers do with the electronic books they buy—what they highlight and bookmark, if they finish the book, and if not, where they bail out—not only knows what readers like, but what they don’t, at a nearly cellular level. This is likely to matter as the company expands its business as a publisher. (Amazon already found that its book recommendation algorithm was more likely than the company’s human editors to convert a suggestion into a sale, so it eliminated the humans.)

Meanwhile, a company called Narrative Science has an algorithm that produces articles for newspapers and websites by wrapping current events into established journalistic tropes—with no pesky unions, benefits, or sick days required. Call me old-fashioned, but in each case, idiosyncrasy, experimentation, innovation, and thoughtfulness—the very stuff that makes us human—is lost. A culture that values only what has succeeded before, where the first rule of success is that there must be something to be “measured” and counted, is not a culture that will sustain alternatives to market-driven “creativity.”

There is no doubt that the Internet—that undistinguished complex of wires and switches—has changed how we think and what we value and how we relate to one another, as it has made the world simultaneously smaller and wider. Online connectivity has spread throughout the world, bringing that world closer together, and with it the promise, if not to level the playing field between rich and poor, corporations and individuals, then to make it less uneven. There is so much that has been good—which is to say useful, entertaining, inspiring, informative, lucrative, fun—about the evolution of the World Wide Web that questions about equity and inequality may seem to be beside the point.

But while we were having fun, we happily and willingly helped to create the greatest surveillance system ever imagined, a web whose strings give governments and businesses countless threads to pull, which makes us…puppets. The free flow of information over the Internet (except in places where that flow is blocked), which serves us well, may serve others better. Whether this distinction turns out to matter may be the one piece of information the Internet cannot deliver.

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust