Two pilots who are flying an airplane together start punching each other in the cockpit. One ejects those members of the crew whom he believes to be close to his rival; the other screams that his copilot isn’t a pilot at all, but a thief. At that moment, the plane spins out of control and swiftly loses height, while the passengers look on in panic.

These are lines from a recent newspaper column by Can Dündar, a Turkish journalist, and I can think of no clearer aid to understanding the perverse, avoidable, almost cartoonish confrontation that has engulfed Turkey since last December, and that threatens to undo the political and economic gains of the past decade.

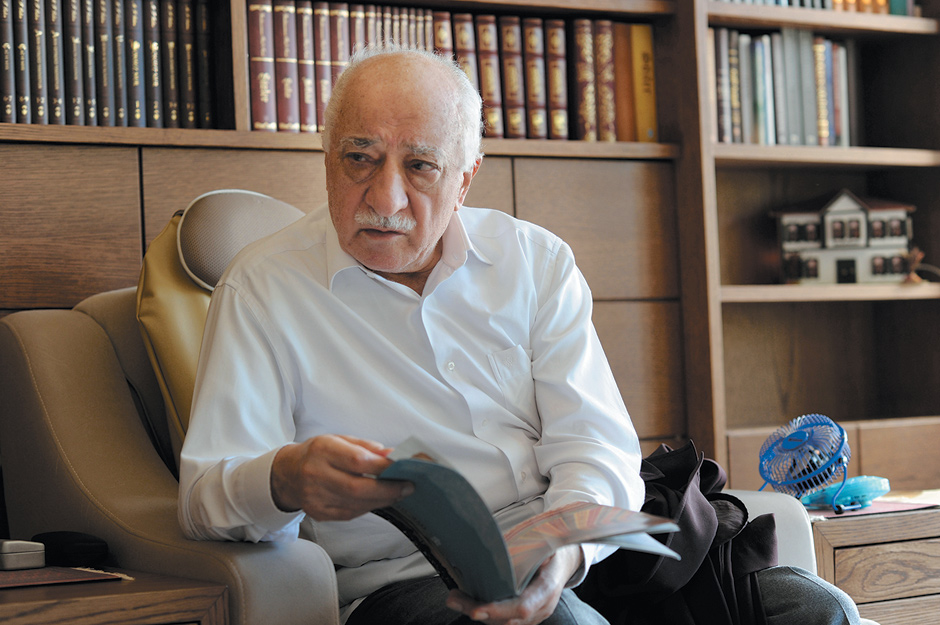

The parties to the confrontation are the prime minister, sixty-year-old Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and a Turkish divine, Fethullah Gülen, thirteen years his senior. Erdoğan leads the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), and works in the political hurly-burly of Ankara, the country’s capital. Gülen is Turkey’s best-known preacher and moral didact. He lives in seclusion in Pennsylvania, reportedly in poor health (he has heart trouble). Gülen presides loosely but unmistakably over an empire of schools, businesses, and networks of sympathizers.

It is this empire that Erdoğan now depicts as a “parallel state” to the one he was elected to run, and he has undertaken to eliminate it. The feud began in earnest last December and has had a remarkably destructive effect. Many of Gülen’s followers work within the government and have had much power. Now large parts of the civil service have been eviscerated, much of the media has been reduced to unthinking carriers of politically motivated revelation and innuendo, and the economy has slowed down after a decade of strong growth. The Turkish miracle is over.

Erdoğan’s AKP government and the Gülen movement share a modernizing Islamist ideology, and although relations between them have been deteriorating for some time, before the current crisis it was possible to be affiliated with both. Coexistence ended abruptly on December 17, when more than fifty pro-AKP figures, including the head of Halkbank, a state-owned bank, a construction magnate, and the sons of three cabinet ministers, were taken in for questioning by prosecutors who are regarded as Gülen’s men.

The raids were allegedly carried out by Gülenist policemen and they were given much attention by newspapers and TV stations with a similar pro-Gülen bent. Allegations that the well-connected detainees were guilty of bribery, smuggling, and other crooked activities were tweeted and retweeted in a frenzy of condemnation; the Gülenist assault from within the government as well as outside it had been well planned. Incriminating evidence was indeed uncovered, including some $4.5 million kept in shoeboxes in the home of the Halkbank chief executive, along with indications of payments to ministers. It soon emerged that a second phase of the same investigation would touch the prime minister’s son.

The speed and vigor of Erdoğan’s reaction to these events indicate that he regarded them as a precursor to his own destruction. He immediately began clearing out compromised or potentially traitorous members of his entourage, and within a few days had replaced half his cabinet, including those members whose sons had been taken into custody. The purge has spread to far points of the civil service. As part of Erdoğan’s campaign against the influence of Gülen, thousands of policemen have been moved from their posts, as well as senior prosecutors involved in the corruption case, and bureaucrats associated with the departed ministers have also been shuffled or dismissed.

Earlier in February the government began investigating Gülenist police officers on suspicion of “forming an illegal organization within the state.” Erdoğan stopped the judicial investigations and instead took direct action. Two months shy of municipal elections, and six months away from a presidential election he hopes to contest, he survives. But the political tradition he represents, a synthesis of Islamism and the free market, is hurt, the prime minister has been badly damaged, and there will be more damage to come.

Before the Erdoğan–Gülen confrontation started to show itself, in early 2013, and certainly before last summer’s nationwide protests, when Turkish liberals took to the streets against their authoritarian prime minister, Turkey’s modernizing Islamist current enjoyed much goodwill. Erdoğan personified it. He came to power in 2003, after a decades-long struggle by Islamists against the oppressive tactics of the country’s long-entrenched secular institutions, notably the army and judiciary. Within a few years of becoming prime minister, Erdoğan seemed to be rectifying many of the country’s problems. Exploiting the strong majority enjoyed by the AKP in parliament, he stabilized and liberalized the erratic, semi-planned economy, making Turks richer than they had ever been, and introduced numerous liberal reforms (such as ending torture and giving increased rights to the Kurds). Perhaps most important of all, he brought under control of the elected civil authorities the armed forces, which had overthrown no fewer than four elected governments since 1960.

Advertisement

All along, the AKP was in an unofficial coalition with less visible Islamists, and their most powerful coalition partner was the movement of Fethullah Gülen. His schools turned out well-behaved, patriotic, pious Turks, and the government welcomed them into the bureaucratic and business elites that gradually displaced the old secular guard. Erdoğan and Gülen seemed to embody the longing of many Turks for an Islam in harmony with electoral democracy, entrepreneurship, and consumerism. And the Islamic element in the formula was supposed to guarantee high standards of ethics and behavior. For years, public life had been venal, loutish, and appetite-driven; the Islamists promised to do things differently.

But the Islamists, too, do not lack for appetites. Shortly after the initial detentions by Gülen’s police allies in December, a video purporting to show a senior AKP figure in flagrante delicto was posted on the Internet. (Abdurrahman Dilipak, a leading pro-government columnist, claimed there were forty more such “doctored” tapes in existence.) Recorded phone conversations involving Gülen have also been leaked and heard by millions. In one he is deciding which Turkish firm should receive a contract offered by a foreign government. In another, he and a lieutenant discuss the likelihood that three “friends” (i.e., followers) in senior positions at Turkey’s banking regulatory body will protect a Gülen-affiliated bank, Bank Asya, from government investigation. (Shortly after the leak, the three officials in question lost their jobs.) All this seemed a long way from the image of a frugal sage ailing gently in the hills of Pennsylvania that Gülen has cultivated.

The tone of the conflict is unrestrained, and is being set from the top. Erdoğan refuses to utter Gülen’s name in public, but when he talks of “false prophets, seers, and hollow pseudo-sages,” his target is clear. In one of the frequent sermons that Gülen delivers from his home, reaching big audiences in Turkey by means of supportive television stations and the Internet, the exiled preacher recently placed a malediction on his enemies, beseeching God to “consume their homes with fire, destroy their nests, break their accords.” Allegations of extensive government corruption, many of them involving rigged contracts for construction projects and the violation of zoning laws, have been repeated by the Gülenist media often enough for many of them to stick. On February 24, recordings of telephone conversations between the prime minister and his son, Bilal, in which the two plan the hiding of tens of millions of euros, were posted on YouTube. The prime minister has called the recordings fabricated, but the posting in question was viewed some two million times in the twenty-four hours after it was uploaded. Even if Erdoğan’s purges of the judiciary and the police mean that there will not be successful prosecutions (and Turkey’s parliamentary immunity will protect some of Erdoğan’s allies), it is hard to imagine the government regaining its former reputation for probity.

The terrain of the dispute is as much commercial as political. The government has accused the Gülen-affiliated Bank Asya of buying $2 billion in foreign currency shortly before December’s police operations, the implication being that bank officials had been tipped off and anticipated the ensuing fall of the Turkish lira. The bank is now struggling to contain a run on deposits that saw its share price fall by 46 percent between December 16 and February 5. Even non-Gülenist financial experts believe that the government has orchestrated the withdrawals in an attempt to ruin Bank Asya, heedless of the collateral damage, both to small depositors and the banking system as a whole, that this would cause. Turkish capitalism is only tenuously governed by the rule of law.

Erdoğan’s image is suffering. Last summer’s protests disclosed to the public a prime minister ruled by rage and fear, as he reacted to the dissatisfaction of a largely secular minority not with magnanimous gestures, which would have satisfied many of the protesters, but with baton charges, tear gas, and denunciations of a plot by outside powers, sustained by a sinister “interest rate lobby,” to deny Turkey its rightful place in the sun. By “interest rate lobby” Erdoğan means unscrupulous Western speculators—Jews, by implication—and his remarks speak to older memories, among them of Turkey’s indebtedness to European bankers in Ottoman times, which weakened the empire before its collapse in World War I. But he is also evoking the grim 1990s, when an inflationary, debt-ridden, and unproductive economy was the plaything of investors who took profits when the markets were up and reentered after the inevitable crash—benefiting from real interest rates that averaged 32 percent.

Advertisement

These traumas have informed Erdoğan’s approach to the monetary aspects of the crisis. Even before December 17, a combination of the Federal Reserve’s tapering of bond purchases, the threat of rising global interest rates, evidence that the Turkish economy was cooling, and political jitters caused by last summer’s protests had reduced the value of the lira by 9 percent. The decline accelerated after the December arrests, but the prime minister only endorsed a hike in interest rates after the value of the currency had fallen by a further 13 percent, and Turkish companies, with their heavy exposure to short-term, dollar-denominated debt, were struggling to meet financial obligations. Finally, on January 28, the Central Bank raised rates and the lira’s fall was arrested.

Erdoğan’s ideological resistance to raising rates has cost Turkish companies dearly. In the words of Inan Demir, an economist at Finansbank, in Istanbul:

There was no choice but to hike, or there would have been full-scale panic, but it should have been done earlier. Now Turkish companies have the worst of all worlds, with continuing difficulties in meeting redemptions, due to the weak lira, and higher financing costs because of the rate hike.

In the space of just four months, Finansbank has revised its growth forecast for 2014 from 3.7 percent to 1.7 percent—after a decade of growth averaging more than 5 percent.

For all its troubles, Turkey’s economy is still big, its citizens 43 percent better off than they were when Erdoğan came to power. This more successful country is the subject of The Rise of Turkey: The Twenty-First Century’s First Muslim Power, a new book by Soner Cagaptay, a Turkey expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. One sympathizes with Cagaptay, who finished his book long before the present crisis, but even then his tone might have struck one as triumphal—a reminder of the tendency of many observers, captivated by the spectacle of Turkey shedding the complexes of the past, to downplay the perils of the future. Cagaptay dwells at length on the political and economic advances of the Erdoğan years, but he does not go into the tensions within Turkish Islamism, which are likely to define the country’s politics for some time, or the corruption that underlies the country’s capitalist successes.

The Rise of Turkey is also quiet about the Gülen movement—except for its part in organizing a glittering international conference, attended by Cagaptay, on Turkey’s “leadership role in the Arab Spring.” Such a conference would be unthinkable now, for Erdoğan’s Muslim Brotherhood allies have been bundled out of power in Egypt and his Syrian policy, predicated on a swift overthrow of Bashar al-Assad, is in disarray. Cagaptay is far from the only academic to have accepted hospitality from the Gülen movement, and his description of it as “prestigious” cannot be contested. But there is more to Fethullah Gülen than prestige.

Gülen: The Ambiguous Politics of Market Islam in Turkey and the World is by an American sociologist, Joshua Hendrick, who worked for seven months as a volunteer editor at a Gülen-affiliated publishing house in Istanbul. As someone who recently spent a couple of days in the company of Gülenists, and who found their beaming, radiant, unswervingly solicitous manner perplexing at first, and then somewhat wearing, I can only admire Hendrick’s longevity. It has paid off, for this is a helpful and detailed account of a movement that is defined, if such a thing is possible, by obfuscation.

Fethullah Gülen denies that he heads a movement or that he has any institutional link to the organizations that revere him. His followers—as many as five million, according to some estimates—say that they do not form a network but are united by their respect for the Hocaefendi, or “esteemed teacher,” and moved by his vision of a modern, tolerant Islam that values knowledge and material progress as well as piety and charity. Companies owned or supported by Gülenists do not identify themselves as such, even if there is an association, the Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists, whose members confess their admiration for him. Consequently it is hard to know how many billions of dollars they are worth. Gülen’s picture does not beam from the walls of the more than one thousand private schools, in more than 120 countries, that have been set up by his adherents, or from the masthead of the Gülen-affiliated Zaman newspaper, Turkey’s biggest.

As Hendrick points out, many people do not even realize that they are in Gülen’s orbit—a parent sending his daughter to a Gülen-affiliated charter school in South Africa, for instance, or a subcontractor working with a Gülenist construction company in Russia. Deniability and ambiguity have been “crucial to the [movement’s] uninterrupted growth for three decades.”

The other factor is Gülen himself. His personal magnetism has been winning followers since the 1960s, when as a young mosque imam he was known for his emotional preaching style, breaking down in tears and even throwing himself onto the floor. A follower who had just returned from visiting the Hocaefendi in the US described him to Hendricks as having “powers that an average educated person…could not possibly imagine. It is God-given.” In some ways Gülen is revered in the same way as a Sufi “pole,” a human being who has been singled out by God to diffuse divine truth, but the Gülen movement is too worldly to be considered a Sufi movement. “Action” is the Gülenists’ declared guiding principle, not detachment and introspection.

Drawing on the teaching of a twentieth-century Turkish divine, Bediüzzaman Said Nursi, Gülen believes that humanity needs to be saved from sin and shown the path of Koranic revelation and prophetic example. From the same starting point, other Muslim revivalists in the twentieth century, notably Egypt’s Sayyid Qutb, justified violence and a harsh application of holy law. Gülen leans the other way. He calls for “embracing people regardless of difference of opinion, worldview, ideology, ethnicity, or belief,” and for “democracy, universal human rights and freedoms”—anathema to Qutb.

Gülen’s worldview goes some way to explain his movement’s internationalism, the emphasis on language-learning at its schools, and its pursuit of inter-faith dialogue through conferences and university endowments. Unlike many other Islamic organizations, the Gülen movement does not raise money solely for fellow Muslims, but for non-Muslims too (the victims of Haiti’s earthquake, for instance). Gülen and his lieutenants go to immense pains to distance themselves from anti-Semitism, and even from criticism of Israel. This has eased the movement’s efforts to establish itself in the United States, where it has around 135 charter schools, and where it has cultivated powerful allies in politics, education, and the arts. Even so, the Gülenists are nowadays the object of increased scrutiny by the American parents who send their children to his charter schools, and who are concerned by the opacity of their aims and methods, and, more generally, by observers who are uncertain what Gülen stands for.

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, education has been the preoccupation of the Muslim reformers—with particular emphasis on the sciences—and the Gülen movement is no different. In Turkey it controls eight universities, dozens of private secondary schools, and some 350 crammers that prepare children for university entrance exams. The state education system in Turkey is poorly regarded, so parents scrimp and save in order to send their child to a crammer.

At one such institution, immaculate, well equipped, and Gülenist, a senior educator told me that Gülen-affiliated crammers send pupils to the country’s best universities, and that they offer 15 percent of their places to poor pupils on a scholarship basis. He broke off our conversation to go to the mosque across the road to say his prayers, before returning with two nice, polite male students (the girls’ section is separate). They told me about the “big brother” system, whereby moral and practical support is provided to pupils far from home who are billetted in the crammer’s dorms. One of the boys remarked that the teachers treat him “like their own son.” The Gülen movement is fond of family analogies. It does not like nine-to-fivers; dedication is prized in both students and teachers.

Wealth, success, the thrill of being party to a sublime truth—the Gülen movement energetically proselytizes, and these are its inducements. It is easy to imagine the debt of obligation felt by the poorer Gülenists after they are lifted into this shiny, cosmopolitan, and above all close-knit world. As much as through the books and speeches of the Hocaefendi, it is through friendship that they are drawn in, and if their families will not accompany them then a choice must be made—between the old family and the new one.

Cults and closed organizations the world over have used similar methods, and the results are not always happy. A psychologist in Istanbul told me about a poor boy, the son of a concierge in the city’s most expensive district, who had visited her after an experience with a group of Gülenists. They had befriended him, inviting him into the home they shared, introducing to him to the Hocaefendi’s ideas, and making him feel clever, accomplished, and accepted. Then one day when the others were out, he was idly flicking through some DVDs and put one on. It was a guide to ensnaring recruits, explaining tactics that he recognized as having been used on him. This is how he ended up visiting my psychologist friend.

Near the beginning of his book, Hendrick reproduces part of a leaked video transcript that was part of the prosecution’s case against Gülen in 2000, when he was being tried in absentia—he had already fled Turkey for the US—for conspiracy against the secular state. In this famous excerpt, Gülen tells his supporters:

You must move in the arteries of the system, without anyone noticing your existence, until you reach all the power centers…. You must wait until such time as you have gotten all the state power.

But Hendrick does not go deeply into the various accusations that have been leveled at Gülen over the years; as a sociologist, he may not feel it is his job to do so.

Claims that Gülen has been trying to take over the organs of the state, particularly the judiciary and the police, date back at least to 1971, when he served a seven-month jail sentence for undermining secularism. These claims rest on an important distinction between the Gülen movement and Turkey’s other Islamist traditions. While the latter reacted in an orthodox way to the legal and political obstacles placed before them, contesting elections and fighting charge sheets, the Gülenists tried to remain on the right side of the secular institutions (not always successfully, as Gülen’s imprisonment shows), while gradually infiltrating them. In 2011, a journalist called Ahmet Şık brought out a book, The Imam’s Army, that shows how the Gülenists took control of the police force over a period of two decades.

The Imam’s Army is full of fascinating details. It contains a directive that was allegedly issued to Gülenist policemen in the late 1990s, at the height of a campaign by the secular authorities against Turkish Islamists. In this directive, Gülen’s followers in the force are ordered to remove his books from their homes, leave empty beer cans around the place, and tell their wives to remove their headscarves so as to give a secular impression. Şık also writes about the transfers and demotions that are the fate of any senior policeman or prosecutor who tries to take on the Gülenists, and the campaigns of vilification waged against them by the Gülen-affiliated media, the newspaper Zaman in particular.

Şık drew some of his material from an earlier book by a former chief of police, Hanefi Avcı. In September 2010, two days before he was due to substantiate his claims in a press conference, and despite his right-wing sympathies, Avcı was arrested and charged with membership in a leftist organization. Şık was arrested the following year, shortly before the planned publication of The Imam’s Army. (Despite the efforts of the police to destroy every digital copy of the book, it was posted on the Internet and was downloaded 100,000 times in two days.) More journalists were arrested, on various pretexts, and the cases of all were folded into a huge investigation into an alleged conspiracy against the government by the old secular establishment. The conspiracy was named Ergenekon, the name of the the mythical Central Asian homeland of the Turkish nation.

When it was launched in 2007, the Ergenekon investigation was welcomed by many Turks as a chance for the country to draw a line under the abuses that had been committed by the armed forces and their allies. But long before the investigation reached its climax last August, with the jailing of 242 people, including a former chief of the general staff, for belonging to the “Ergenekon terrorist organization,” blatant irregularities in the case had caused some to change their minds. Convictions were secured on the basis of illegal wiretaps; there were numerous instances of incompetently planted evidence. Perhaps most egregious of all, in a related case, 330 serving and retired members of the armed forces were jailed for plotting a coup in 2003—even though the prosecution’s case rested on a single CD whose formatting showed it used the 2007 version of Microsoft Office.

Ergenekon was to have been the final vindication of Turkey’s long-suppressed Islamists and Erdoğan as their leader; but there is good reason to argue that there never was an organization called Ergenekon and that the legal process was motivated by malice and revenge. According to Gareth Jenkins, a British scholar who has penetratingly analyzed the case, it was put into operation not by Erdoğan but by a “cabal of Gülen’s followers in the police and lower echelons of the judiciary.” As it went on, Jenkins maintains, the Gülenists’ misuse of it to victimize their enemies increased. Jenkins believes that Ahmet Şık, Hanefi Avcı, and the other arrested journalists—some of whom still await sentencing—have been punished because they are “critics, opponents or rivals of the Gülen movement.”

Back in 2006, Fethullah Gülen was acquitted of trying to take over the Turkish state, but Erdoğan, his former ally, has revived the idea. Having been a supporter of the Ergenekon investigation, Erdoğan is now keen for the files to be reopened, no doubt with a view to exposing judicial abuses by the Gülenists. Last month Erdoğan responded with an abuse of his own, steering legislation through parliament that gives the government increased control over judges and prosecutors. The two men’s dispute marks the end of a partnership that brought Islamism to power in Turkey, and it challenges the belief, once entertained even by some liberals, that if Turkey was more responsive to its pious majority it would also be more just.

—March 6, 2014