As he had lived, Cornelius Gurlitt died at eighty-one early in May, in thrall to a trove of inherited art he kept hidden for decades mostly at a modest apartment in Munich. The announcement last year of the collection’s discovery by German authorities yanked the reclusive Gurlitt from the shadows. Stories about him busied the front pages of newspapers for weeks.

He seemed a figure out of Sebald or Kafka. He had never held a job, kept no bank accounts, was not listed in the Munich phone book. Aside from sporadic visits to a sister, who lived in Würzburg and died two years ago, he had had little contact with anyone for half a century. Der Spiegel reported that he had not watched television since 1963 or seen a movie since 1967, and that he had never been in love, except with his collection.

The art, nearly 1,300 works, some of which belatedly turned up in a second home in Salzburg, was mostly nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century European pictures, a good deal of it what the Nazis called Entartete Kunst, or degenerate art, who knows how much of it seized from museums and Jews. Cornelius’s father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, accumulated the collection. Under the Nazis, Hildebrand was dismissed from two museum posts—one in Zwickau, “for pursuing an artistic policy affronting the healthy folk feelings of Germany” by exhibiting modern art, the other in Hamburg, partly for having a Jewish grandmother. But then Goebbels handpicked him, among a few others, to sell abroad confiscated modern works. That is how Hildebrand spent the war years, placating his Nazi bosses while enriching himself, then afterward lying to Allied investigators about the destruction of his collection in Dresden.

He died in a car wreck in 1956. His widow, Cornelius’s mother, died a dozen years later, when Cornelius seems to have taken over the collection, selling the occasional picture to stay afloat but otherwise holding the art as a sort of sacrament. His father had written a self-serving essay shortly before his death describing the collection “not as my property, but rather as a kind of fief that I have been assigned to steward,” which Cornelius clearly took to heart, until his nervous behavior on a train from Zurich made Bavarian customs officers suspicious.

Early in 2012, police, customs, and tax officials descended on his Munich apartment and spent three days removing works by Picasso, Matisse, Otto Dix, Emil Nolde, and Oskar Kokoschka, along with older artists like Renoir, Courbet, Dürer, and Canaletto. Gurlitt was ordered to sit and watch. He told Der Spiegel that it was worse than the loss of his parents or his sister. By the time newspaper and television reporters discovered him and his story more than a year later, he was ill and bereft.

The usual media chatter focused on how much Gurlitt’s hidden art was worth, a noise that competed with the sound of slow, grinding wheels, justice belatedly turning toward restitution. “All I wanted was to live with my pictures,” Gurlitt said, but of course who knows how many original owners of the works would have said the same, had Hitler’s henchmen not stolen the art from them. In Gurlitt’s ruin, and the liberation of captive art, one could also make out the twisted echoes of families discovered hiding in attics, of fleeing refugees unmasked on trains.

A culprit, a figure divorced from time—far removed from a century of hedge fund investors buying $100 million paintings—Gurlitt loved the art he hoarded truly and too well. The pictures survived him, like Paul Celan’s bottles tossed into the ocean, suddenly returned from oblivion, inevitable tokens of lives lost and reminders of art’s endurance. Hitler couldn’t exterminate modern art—the great Jewish Bolshevik cultural conspiracy, as he saw it—whose daring and pungency, obscured by today’s babble about money, somehow gained new life in the story of Gurlitt and the Nazis’ degenerate campaign.

I suspect this partly explains the popularity of “Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937,” at the Neue Galerie in New York, where lines stretched out the door as soon as the show opened in March. Seeing the exhibition, you can recover a sense of what was once radical and thrilling about pictures by Expressionists like Max Beckmann, George Grosz, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. A debased term, the avant-garde gets its jive back. Art matters again. The Nazis raised the stakes by stigmatizing modern art. As Genet once put it, fascism is theater. So modernism returns to its role as tragic hero in the show.

It is organized by Olaf Peters, an art historian and board member of the Neue Galerie, whose founder, the billionaire collector Ronald Lauder, was United States ambassador to Austria and outspoken on issues of Nazi repatriation. The exhibition retraces ground covered a generation ago in a 1991 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Far larger than this show, that one, put together by the curator Stephanie Barron, also revolved around the notorious 1937 “Entartete Kunst” exhibition in Munich that the Nazis mounted to coincide with the opening of the first “Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung,” or Great German Art Show, of approved Nazi art. Barron recovered nearly two hundred of the 650 works crammed into the original show in Munich, along with Nazi films and archives. The Los Angeles catalog provided a wealth of information, illustrations, and biographical details, many about German artists who had slipped down the memory hole.

Advertisement

The Neue Galerie exhibition condenses the same story into a handful of rooms. It is modest in size but ingenious, poignant, pointed. It traces the concept of degeneracy back to its well-known roots in the writing of a nineteenth-century rabbi’s son, Max Nordau, and connects the 1937 “Entartete Kunst” to smaller Schandausstellungen, Exhibitions of Shame, staged by extremists earlier in the 1930s in cultivated cities like Dresden.

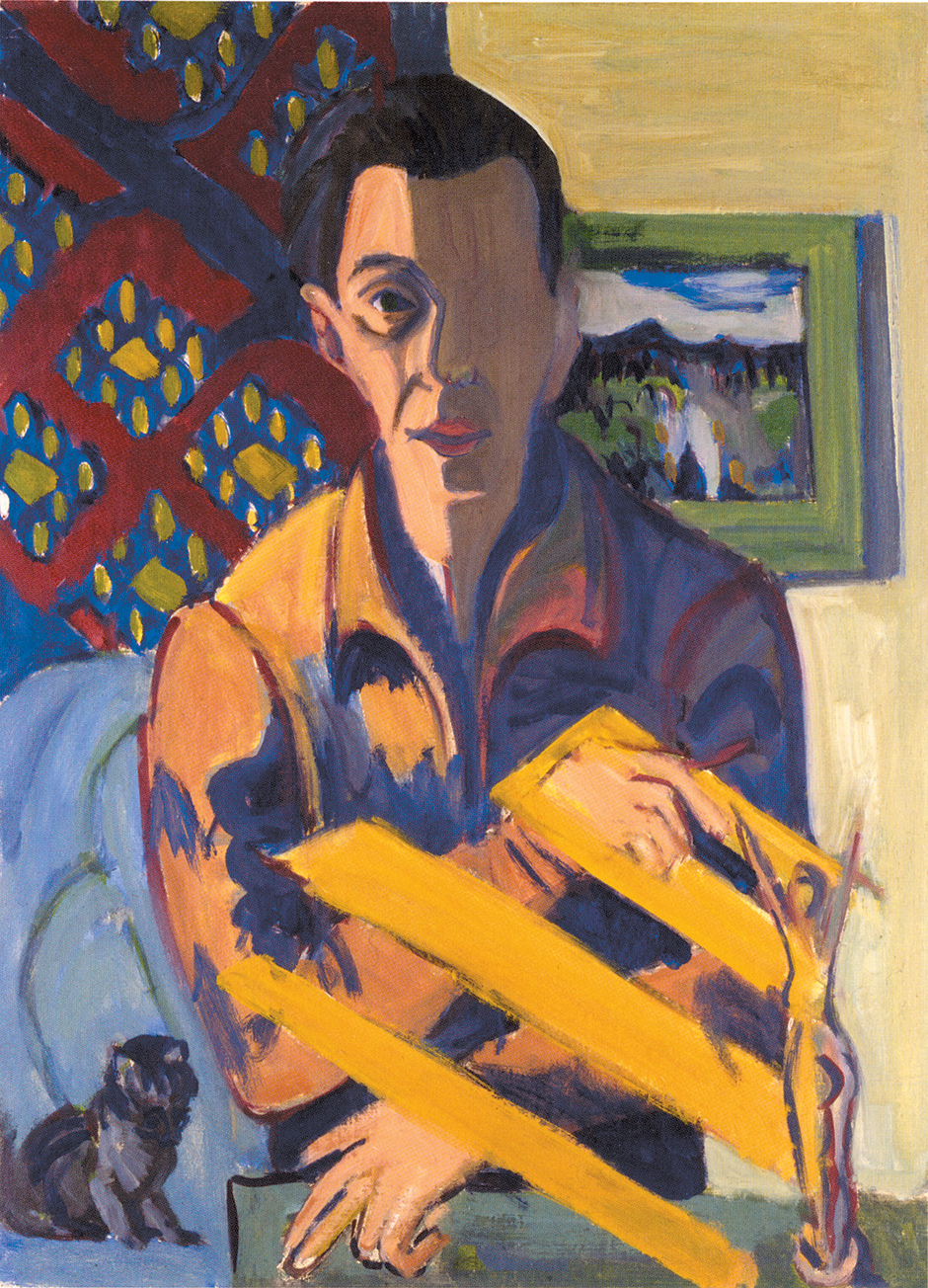

The New York show brings together vivid propaganda and photographs, identifying the degenerate art campaign as a prelude to extermination. It recovers empty picture frames from paintings now lost, which speak volumes hung side by side. Artists like Paul Klee come across as genuine provocateurs. A suite of Klee’s twittering, toylike pictures, with their spidery symbols and scribbly shapes, whimsical and ingenious, indebted to children’s art and the art of the insane, were like Davids to the Nazi Goliath. And it’s hard to miss the heartbreak in a self-portrait by Kirchner, the artist staring straight ahead, face half in shadow, or more likely erased, a work begun in 1934 but finished in 1937, when Kirchner added yellow bands, like bars, almost forming a swastika, handcuffing his wrists. The Nazis had confiscated hundreds of Kirchner’s works that year and put dozens in “Entartete Kunst.” A fragile, sickly man, Kirchner committed suicide, an early victim of Hitler’s cultural cleansing.

The show’s opening room lays it all out, pitting works from “Entartete Kunst” against art from the “Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung,” or GDK, a clash encapsulated by the pairing of two large triptychs: Beckmann’s Departure (1932–1935) is a dark riddle about torture and loss; Adolf Ziegler’s The Four Elements (1937), an academic quartet of marmoreal, Teutonic nudes, as mundane as the Beckmann looks mysterious, exemplifying what Susan Sontag meant when she wrote years ago in The New York Review about fascist nudes being “sanctimoniously asexual.”

It was Ziegler who gave the opening speech for “Entartete Kunst” in 1937 (“monstrosities of madness, of impudence, of inability and degeneration,” he said, calling the artists “pigs”); and Hitler hung The Four Elements over his fireplace at the Führerbau in Munich, until Ziegler fell out of favor, for joining secret peace negotiations with the Allies in 1943. Dachau was his penalty.

The show also pairs works like Richard Sheibe’s bronze Decathlete (1936), a typically airless Nazi nude, with Karel Niestrath’s Expressionist Hungry Girl (1925), emaciated, streamlined, proud. Sculpture seems to have mattered more than painting to the Nazis because it could be large, outdoors, and lent itself to the glorification of the Reich and the cult of the body. But one still senses a fuzzy, almost arbitrary line that often divided banned from accepted art. Sometimes there’s hardly any difference at all. At the same time, the Nazis borrowed modernist graphics to vilify modernism. Peters has told me that he believes that the big public misconception is that there was, from National Socialism’s early days, a cultural master plan, an aesthetic agenda.

But there wasn’t. Culture’s role for the Reich was improvised, ad hoc. Here the catalog makes fascinating reading for its accounts of the organization of both the GDK and “Entartete Kunst.” Ines Schlenker, an art historian, in an essay about the GDK, writes how, when fire destroyed Munich’s traditional exhibition hall, a new building was commissioned for which Hitler laid the cornerstone. The Haus der Deutschen Kunst was one of the early Nazi monuments, a neoclassical temple of marble and light with a grand colonnade and a skylit nave, built to showcase the art Hitler liked. Its first big exhibition was to be the 1937 “Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung.” Some 554,759 people attended the GDK, fewer than the two million who saw “Entartete Kunst,” but as Schlenker writes, the Nazis inflated the degenerate figure by mass visits of party organizations, enacting rituals of derision.

The GDK number exceeded attendance at all other contemporary art events in Germany that year. In subsequent years, attendance for the annual GDK shows rose, peaking at 846,674 in 1942. Hundreds of works were sold out of these exhibitions to buyers seeking favor with the regime. The Nazis touted the sales as proof that Germans loved Nazi art.

Advertisement

But what was Nazi art? It was, from the start, whatever Hitler felt at the moment. For a while there was a chance it was going to be a kind of Nordic Expressionism, until the Führer decided it wasn’t. Beckmann, Kirchner, and Oskar Schlemmer imagined working with the state as late as June 1937, when Hitler ordered thousands of their works and others impounded from German collections. The Bauhaus had had hopes, too, until it didn’t. Organizers of the first GDK sent invitations to Nolde, Ernst Barlach, and Rudolf Belling, all of whom would simultaneously end up in “Entartete Kunst.”

Nolde, who had participated in an exhibition of young National Socialists in Munich, was infuriated. Along with Barlach and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, he had signed a loyalty oath to Hitler after Hindenburg died. More than one thousand of his pictures were confiscated from German museums, and twenty-seven included in the degenerate display. As for Belling, the Nazis were so confused and disorganized that a bronze sculpture he did of the boxer Max Schmeling made it into the first GDK while two other works of his simultaneously landed in “Entartete Kunst.” An open call to contribute to the GDK had been issued to German artists months earlier with the empty promise “to neither favor specific art trends nor exclude others in the selection of the works.” This elicited 15,000 submissions, whittled down by a jury for inspection by Hitler, whom Goebbels recorded in his diaries as “wild with rage” at the results.

“The sculptures are passable, but the paintings are in some cases outright catastrophic,” Goebbels noted. Hitler fired the jury and enlisted a friend, Heinrich Hoffmann, who shared his taste for nineteenth-century Bavarian kitsch: genre paintings, classical nudes, portrait busts, animal pictures. The exhibition opened on July 18, 1937, with nearly nine hundred works by more than five hundred artists. It was a mess.

Peters writes that “Entartete Kunst” was devised by Goebbels in part to obscure the failings of Nazi-approved art. An admirer of Expressionism before Hitler condemned it, Goebbels recorded the idea for an Entartete Kunst exhibition in his diary on June 4, 1937, just weeks before the show opened. He imagined an exhibition (at first in Berlin) of “works from the era of decay. So the people can see and understand.” The era was Weimar Germany, with its cultural prologue in the fin de siècle. Peters believes that Goebbels cooked up the degenerate display because he felt threatened by Hoffmann and fearful when two of his allies were among the jurors dismissed from the GDK. This was how he wanted to get back into Hitler’s favor.

The show was hurriedly crammed into the galleries used for the plaster cast collection at Munich’s Archaeological Institute, not far from the Haus der Deutschen Kunst. Walls were painted with mocking texts, to silence skeptical visitors. A crucifixion by Ludwig Gies was hung at the entrance, a provocation to devout Christians who couldn’t recognize the work’s clear Gothic debts, mobilizing what Peters calls “Catholic-tinged anti-Semitic resentment” against modernism—notwithstanding that the Nazis had risen to power on an anticlerical platform.

Much was made in the exhibition of modernist contortions of the human body, of antiwar art by figures like Grosz. Carl Linfert, reviewing the show in Die Frankfurter Zeitung in November 1937, could not fail to see “Entartete Kunst” as a diversionary tactic. “Goebbels and Hitler sought refuge in revenge and radicalization,” as Peters sums up Linfert’s argument. “If they could not establish anything significant themselves, they could at least manage to destroy the hated counterimage.”

It would be a few more years before modern art was used directly to justify mass murder, in propaganda films and literature, with Himmler pushing a concept of culture infecting the masses like a plague “against the healthy body.” Works by Otto Freundlich, who would be murdered at Majdanek, were juxtaposed with nudes by Josef Thorack in SS brochures. Degenerate art, Himmler wrote, spread through the culture; it had the same effect as the “mixing of blood.” From 1937 to the early 1940s, the notion of degenerate art underwent “a deadly transformation,” as Peters writes.

That transformation now seems inevitable, but clearly art had remained a moving target for the Nazis, an existential threat, which haunted Germany’s fate and still does. Sebald described in The Emigrants a forgotten Alpine climber whose bones suddenly turn up in a glacier decades after he had disappeared. “And so they are ever returning to us, the dead,” he wrote. A few years ago, workers digging a new subway station near City Hall in Berlin unearthed a rusted bronze bust of a woman, a portrait, as it turned out, by Edwin Scharff, one of those forgotten German modernists. Soon more banned sculptures emerged at the construction site, eleven in all; a couple of them had been exploited in one of the more notorious Nazi propaganda films. They were known to have been stored in the depot of the Reichspropagandaministerium, which organized “Entartete Kunst.” German authorities concluded that they ended up near City Hall because they came from a former building across the street. During the war, a tax lawyer and escrow agent, Erhard Oewerdieck, kept an apartment at 50 Königstrasse. He is history’s answer to Gurlitt, the Munich hoarder.

Oewerdieck is remembered at Yad Vashem. He helped the historian Eugen Taübler and his wife flee to America, preserving part of Taübler’s library. He and his wife gave money to another Jewish family to escape to Shanghai. He hid an employee in his apartment. German investigators today guess that, having somehow got hold of the sculptures from “Entartete Kunst,” he hid them in his office before fire from Allied raids in 1944 consumed the building, which collapsed, burying the office’s contents.

So the art remained for all these years until the workers digging for the subway turned up, like the police and customs agents at Gurlitt’s door, like the bones of Sebald’s Alpine climber.

This Issue

June 19, 2014

Looking for Ukraine

Irresistible El Greco