Within days of the publication of No Place to Hide by the journalist Glenn Greenwald, a photograph began circulating on the Internet that showed National Security Agency operatives surreptitiously implanting a surveillance device on an intercepted computer. After nearly a year of revelations about the reach of the NSA, spawned by Edward Snowden’s theft of tens of thousands of classified documents, this photo nonetheless seemed to come as something of a surprise: here was the United States government appropriating and opening packages sent through the mail, secretly installing spyware, and then boxing up the goods, putting on new factory seals, and sending them on their way. It was immediate in a way that words were not.

That photo itself was part of the Snowden cache, and readers of Greenwald’s book were treated to the NSA’s own caption: “Not all SIGINT tradecraft involves accessing signals and networks from thousands of miles away,” it said.

In fact, sometimes it is very hands-on (literally!). Here’s how it works: shipments of computer network devices (servers, routers, etc.) being delivered to our targets throughout the world are intercepted. Next, they are redirected to a secret location where Tailored Access Operations/Access Operations…employees…enable the installation of beacon implants directly into our targets’ electronic devices. These devices are then re-packaged and placed back into transit to the original destination. All of this happens with the support of Intelligence Community partners and the technical wizards in [Tailored Access Operations].

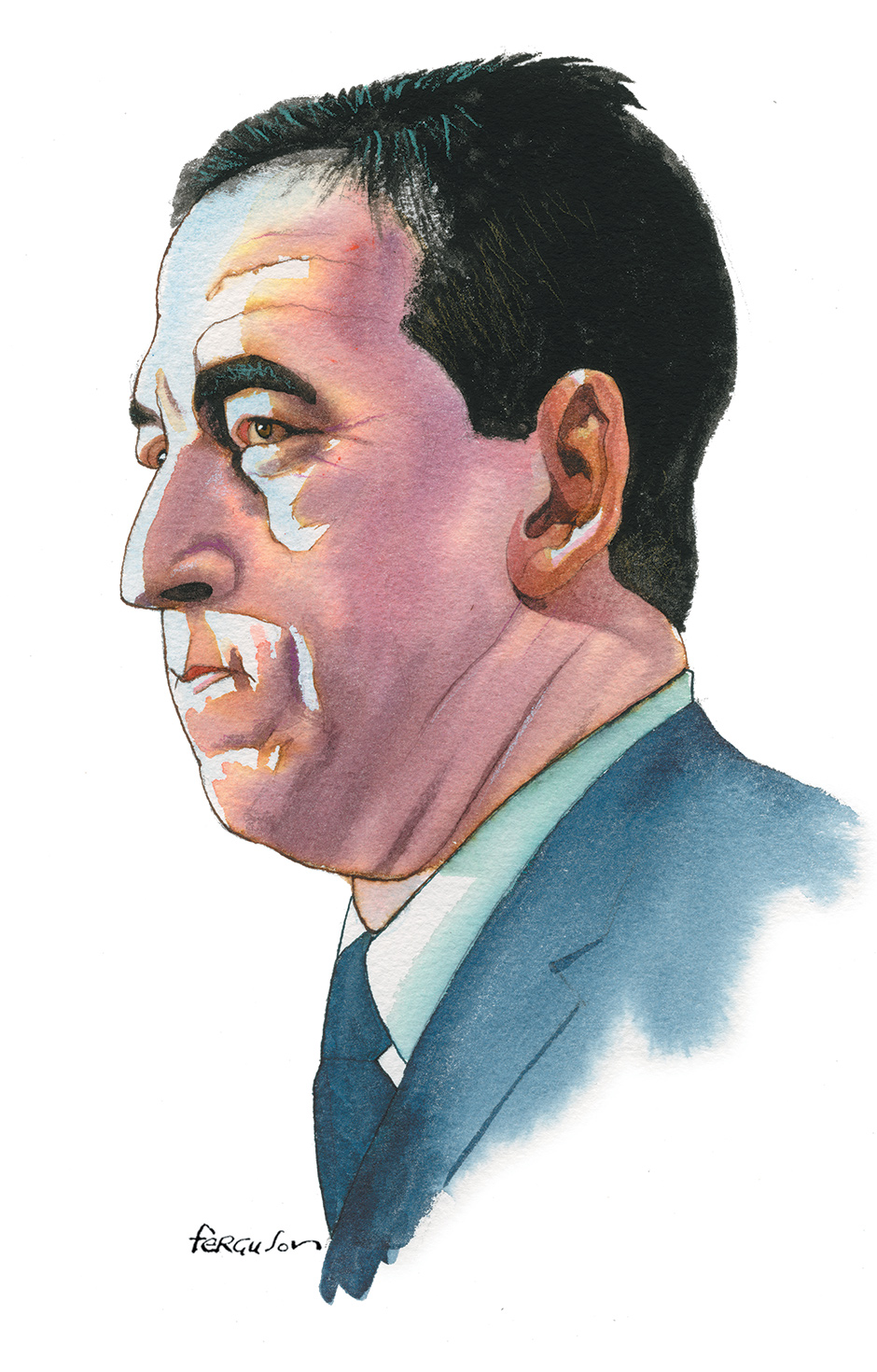

Edward Snowden, as we all now know, was another kind of NSA technical wizard, whose job entailed teaching agents how to shield their digital devices from surveillance and designing systems to thwart other countries cyberspying on the United States. Though he was in his twenties and without traditional educational credentials, having neither a college nor a standard high school degree, Snowden’s computer abilities gained him ever-increasing security clearances, even when he was not an employee of the United States government but, rather, a contract worker. This, we’ve learned, was not unusual. As Greenwald reports, the NSA employs twice as many civilian contractors—60,000—as it does agency employees—30,000—many of whom hold “confidential” and “top secret” security clearances.1

As Greenwald describes him, Snowden was a libertarian with a patriotic bent. His father was career military, and he himself enlisted in the army in 2004 determined to fight in Iraq, only to break both legs during training, resulting in his discharge. From there he went to work for the CIA, first as a security guard and then, within a year, in an information technology position. Two years later he was sent to Geneva, “undercover with diplomatic credentials,” as a systems administrator working on, among other things, cybersecurity.

It was in Geneva that Snowden first grew disillusioned with American spy craft. As he told Greenwald, his complaints to superiors about what he considered to be ethical lapses were dismissed and ignored:

They would say this isn’t your job, or you’d be told you don’t have enough information to make those kinds of judgments. You’d basically be instructed not to worry about it…. This was when I really started seeing how easy it is to divorce power from accountability, and how the higher the levels of power, the less oversight and accountability there was.

It is here that Edward Snowden’s story begins to sound much like those of Thomas Drake, William Binney, Kirk Wiebe, and Edward Loomis, longtime NSA employees who, a few years earlier than Snowden, attempted to raise concerns with their superiors—only to find themselves rebuffed—about what they perceived to be NSA overreach and illegality when they learned that the agency was indiscriminately monitoring the communications of American citizens without warrants. Binney, Wiebe, and Loomis resigned—and later found themselves the subjects of FBI interrogations. Drake, however, stayed on and brought his suspicions to the office of general counsel for the NSA, where he was told: “Don’t ask any more questions, Mr. Drake.” Frustrated, Drake eventually leaked what he knew to a reporter for The Baltimore Sun. The upshot: a home invasion by the FBI, a federal indictment, and the threat of thirty-five years in prison for being in possession of classified documents that, when he obtained them, had not been classified. After years of harassment by the government and Drake’s financial ruin, the case was dropped the night before trial.

It was against this backdrop that Snowden found himself contemplating what to do with what he knew. Stymied by an unresponsive bureaucracy, seeing the fate of earlier NSA whistleblowers, and finding no adequate provisions within the system to challenge the legality of government activity if that activity was considered by the government to touch on national security, he nonetheless set about gathering the evidence to make his case. He told no one, not even the woman with whom he lived, going so far as to change jobs, taking a pay cut to get better access to the material he sought.

Advertisement

At some point he came up with a plan: index and catalog the documents and turn them over to journalists, specifically to Glenn Greenwald, who was both a lawyer and a columnist for The Guardian, where he had written at length about national security abuses, to the Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras, and to Barton Gellman, whose work at The Washington Post on the war on terror had earned him two Pulitzers, all of whom he believed would be sympathetic to his mission.

“I selected these documents based on what’s in the public interest,” Snowden told Greenwald and Poitras, when the two of them met with him in Hong Kong, a tale told in high cloak-and-dagger style by Luke Harding in The Snowden Files, and similarly by Greenwald in his book, though with more immediacy. “But I’m relying on you to use your journalistic judgment to only publish those documents that the public should see and that can be revealed without harm to any innocent people.” And, Greenwald writes,

He also stressed that it was vital to publish the documents journalistically—meaning working with the media and writing articles that provided the context for the materials, rather than just publishing them in bulk…. “If I wanted the documents just put on the Internet en masse, I could have done that myself.”

In so saying, Snowden was distinguishing his strategy from that of Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange, and WikiLeaks, who conspired to dump a stunning number of classified military and national security documents onto the Internet with little regard for consequences. While this distinction seemed academic to many critics of Snowden, Greenwald, The Guardian, and others involved in the dissemination of the documents (especially last summer when Greenwald was turning out story after story), once No Place to Hide was out this distinction became less theoretical. Days after publication, Greenwald wrote a piece for the online magazine The Intercept (which he helped found in February), in which he revealed that the NSA is listening to, reading, and collecting every phone call and Internet communication generated in the Bahamas. He also disclosed that the NSA was doing the same thing in another, unnamed, country—a country that he had been asked by the government not to identify for fear of repercussions, and he had agreed.

Enter WikiLeaks. Soon after Greenwald’s piece was posted, WikiLeaks issued an ultimatum to The Intercept: name the second country within seventy-two hours, or it would. Some seventy-seven hours later, in light of Greenwald’s refusal, Julian Assange, the face of WikiLeaks, issued a statement that read in part:

By denying an entire population the knowledge of its own victimisation, this act of censorship denies each individual in that country the opportunity to see an effective remedy, whether in international courts, or elsewhere…. We do not believe it is the place of media to “aid and abet” a state in escaping detection and prosecution for a serious crime against a population.

And then he named the country.

This critique of Greenwald’s journalistic ethics from the left is bookended by the one that has come from the right, understandably, and from the center, quite vociferously. Michael Kinsley’s New York Times review of No Place to Hide is emblematic of the illiberal bluster that has moved the debate from the message—the extensive, often arbitrary, and sometimes criminal activities of the United States spying apparatus—to the messenger, with personal attacks on Greenwald for working with Snowden to bring those activities to public scrutiny. In these formulations, Greenwald is a narcissist, a scofflaw, a traitor, a dogmatist, a self-proclaimed ruthless revolutionary, while those who find value in his reporting are, at best, fools. Kinsley writes:

It seems clear, at least to me, that the private companies that own newspapers, and their employees, should not have the final say over the release of government secrets, and a free pass to make them public with no legal consequences….

So what do we do about leaks of government information? Lock up the perpetrators or give them the Pulitzer Prize? (The Pulitzer people chose the second option.) This is not a straightforward or easy question. But I can’t see how we can have a policy that authorizes newspapers and publishers to chase down and publish any national security leaks they can find. This isn’t Easter and these are not eggs.

But Greenwald and Gellman, with whom he shared the Pulitzer,2 didn’t just publish any national security leak. They published a series of stories detailing enormous electronic monitoring programs undertaken by the government that arguably broke the law. And they demonstrated how, in other cases, the executive, using secret courts, has worked a sleight-of-hand to make legal what in the past would not pass that test. Before publication, those stories were vetted by lawyers. In Gellman’s case, they were also vetted by people at the NSA, the Pentagon, the White House. According to Gellman, speaking on C-Span last April:

Advertisement

There’s lots of stuff in the Snowden archive we did not consider publishing…. My first conversation with the director of national intelligence about that first document, was: “Just so you know, everything between pages seventeen and twenty-four we’re not even considering.” Because it’s operational, it’s specific, it reveals targets, it reveals successes, it reveals techniques.

Greenwald, although critical of the Post, writes that The Guardian showed his stories to the government before publication.

As journalists, Greenwald and The Guardian and Gellman and The Washington Post were making the same kind of judgments as Daniel Ellsberg and the editors who printed the Pentagon Papers, or Seymour Hersh and the editors who chronicled My Lai. That is why Snowden released the material to them and not to the public at large. “He does not try to direct, suggest, hint at what should be written,” Gellman said that day on C-Span.

And when he gave us—the general agreement I made with him, which didn’t require an agreement, because it’s what I would have done anyway, is to look through the material and weigh it carefully, to not dump a high volume of it out there, and consider what the balance ought to be.

That is what investigative journalists do. Or did. We are in a new age, when journalism itself is suspect. As the former New York Times executive editor Jill Abramson pointed out not long ago on National Public Radio:

Sources who want to come forward with important stories that they feel the public needs to know are just scared to death that they’re going to be prosecuted…[and] reporters fear that they will find themselves subpoenaed….

A democracy without a press that is able to track down and publish evidence of malfeasance loses a critical check on unbridled government power. This is why the United States has a free press and a constitutional amendment enshrining it, just as there is a fourth amendment to protect privacy. Reading Greenwald’s account, or watching the Frontline documentary United States of Secrets, or parsing the government’s cases against the New York Times reporter James Risen, who has been under threat of jail for refusing to disclose a source, one sees how both amendments have been compromised by the open-ended “war on terror.” In the words of jailed former CIA analyst John Kiriakou, who leaked information about torture to reporters and in the process revealed the name of a colleague:

First, it was anarchism, then socialism, then communism. Now, it’s terrorism. Any whistleblower who goes public in the name of protecting human rights or civil liberties is accused of helping the terrorists.

Before Barack Obama became president, only three Americans had ever been charged with leaking classified information under the Espionage Act of 1917. In his six years in office, Obama has tripled that number, with Snowden, Drake, and Kiriakou among that group. In Abramson’s estimation, “using an obscure provision of an old law, [the Obama administration is] tip-toeing close to things that, here in the United States, we’ve never had.”

In his review of Greenwald’s book, Kinsley calls Greenwald a “sourpuss” and chastises him for a number of personality defects. This has been a common theme in the book’s reviews, especially those written by mainstream journalists. They don’t like Greenwald’s attitude. And the reason they don’t like his attitude is because, for the most part, he doesn’t like theirs. As much as No Place to Hide is a catalog of the many ways the government casts wide spy nets using computers and cell phones, it is also one man’s rage against the corporate journalism machine, in which most reporters and editors and newspaper companies are cast as spineless government collaborators.3 Greenwald is indignant, self-righteous, and self-aggrandizing—but so what? It’s a red herring, just as focusing on Snowden—who is he, where is he—is a distraction. The matter at hand is not their story; as long as this is a democracy, it has to be ours.

The revelations offered by Greenwald via Snowden, first in the press, now in the book, fall into three basic categories: how the NSA uses the Internet and cellular networks to spy on non-Americans, how it uses the Internet and cellular networks to engage in economic espionage, and how it uses the Internet and cellular networks to spy on Americans. While no one, including Greenwald and Snowden, disputes the necessity of seeking out and monitoring the communications of known terrorists and their associates, what seemed to disturb Snowden the most, as it did the earlier NSA whistleblowers, was the indiscriminate reach of such spying into the lives of everyday, innocent Americans. Greenwald writes about an NSA program called PRISM that “allowed the NSA to obtain virtually anything it wanted from the Internet companies that hundreds of millions of people around the world now use as their primary means to communicate.” Verizon, AT&T, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and every other major Internet company—nine in all—have been providing access to the personal communications of, potentially, every American—phone calls, e-mails, text messages, documents stored in the cloud—to the NSA secretly, and without a warrant, as a matter of course. This is legal only because of the 2008 FISA Amendments Act, which gives the NSA the right to monitor non-Americans and anyone with whom they communicate, including Americans living in America.

Greenwald also writes about the NSA’s BOUNDLESS INFORMANT program, which captures and analyzes billions of telephone and e-mail data generated by Americans in the United States. One slide from an internal NSA briefing on BOUNDLESS INFORMANT shows that a single unit of the NSA “collected data on more than 3 billion telephone calls and emails that had passed through the US telecommunications system” in one month in 2013.

While defenders of the program, like Dianne Feinstein, chair of the Select Senate Committee on Intelligence, point out that the NSA only collects “metadata”—who is communicating with whom, when, where, and about what subject—others, including former assistant CIA director Michael Morrell and Princeton computer science professor Edward Felton, have pointed out that metadata is content. Felton stated in his Declaration to the Court in a lawsuit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union last year against James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, Keith Alexander, the then director of the NSA, Defense Secretary Charles Hagel, and Attorney General Eric Holder:

The structured nature of metadata makes it very easy to analyze massive datasets using sophisticated data-mining and link-analysis programs…. Individual pieces of data that previously carried less potential to expose private information may now, in the aggregate, reveal sensitive details about our everyday lives—details that we had no intent or expectation of sharing.

This could be, for example, a person’s Web searches about sexually transmitted diseases and a call to a rape hotline and credit card payments to a hospital, a pharmacy, and a therapist—you connect the dots. It could be a reporter talking to a source. And it could create false implications: a political activist who buys a pressure cooker on Amazon and searches for two-inch-square nails on Google may look suspiciously like a terrorist, not someone hoping to fix a dining room table before the guests arrive.

And then there is a program that “the NSA calls X–KEYSCORE, its ‘widest-reaching’ system for collecting electronic data,” which can watch people in real time as they move around the Internet, looking at websites, sending e-mails, searching Google, chatting. X–KEYSCORE is also able to watch activity on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. As Greenwald describes it (with accompanying slides from the NSA), “An analyst enters the desired user name on, say, Facebook, along with the date range of activity, and X–KEYSCORE then returns all of that user’s information, including messages, chats, and other private postings.” To do so, the NSA analyst is not required to obtain a warrant or clear the search with a supervisor. Rather, he or she need only file a form requesting access, and like a key turning in a lock, the analyst has access to the information. What this means, too, is that anything that is stored in the cloud—your e-mail, your documents, your text messages—is there for the taking.

X–KEYSCORE, BOUNDLESS INFORMANT, PRISM, and SOMALGET (in the Bahamas) are just a few of the surveillance programs used by the NSA to hoover up the telecommunications of Americans and citizens of other nations. All support General Keith Alexander’s mission when he was NSA chief to “collect it all,” a goal that had its origin during the Iraq war, when he sought to obtain all communications data in and out of that country.

This, it turned out, set the stage for extending the reach of the NSA domestically. Greenwald cites an article in Foreign Policy in which an unnamed former intelligence official observed that Alexander’s view was: “Let’s not worry about the law. Let’s just figure out how to get the job done.” And getting the job done—if the job is collecting electronic data, and not, say, figuring out that two disaffected Chechen-Americans were plotting to detonate pressure-cooker bombs at the Boston Marathon—is what Alexander has accomplished. Under his authority, Greenwald writes, the NSA “was processing more than twenty billion communications events (both Internet and telephone) from around the world each day.”

Whether this has made the country safer may be unknowable, though the President’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technology, convened by the executive in response to the Snowden revelations, concluded that it has not. In its report to the president last December, it wrote: “Our review suggests that the information contributed to terrorist investigations by the use of…telephony meta-data was not essential to preventing attacks.” The Review Group went on to recommend that

as a general rule, and without senior policy review, the government should not be permitted to collect and store all mass, undigested, non-public personal information about individuals to enable future queries and data-mining for foreign intelligence purposes.

In May of this year, following the Review Group’s report, the House of Representatives passed an NSA reform bill, the USA Freedom Act, that had become so diluted that a number of its original sponsors refused to support it. Still, Patrick Leahy, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, remained hopeful that when the bill was finally signed into law it would curb the grossest excesses of domestic spying, particularly bulk collection of electronic data. “You can only imagine what would have happened if someone like J. Edgar Hoover had had availability of this,” Senator Leahy said in January, invoking a bit of institutional memory.

By “this” he was referring to the Internet, where the government (and hackers) have many ways to infiltrate our private lives, and where, in addition, many of us routinely give up personal information mindlessly, as a matter of course, using social media, search engines, and online shopping portals, where it is scooped up by commercial data brokers. One company, Acxiom, for example, has profiles on 75 percent of all Americans, each with around five thousand individual data points that can be constructed and deconstructed to find, say, people who live near nuclear power plants who support Greenpeace, or practicing Muslims who own guns. It should come as no surprise that the NSA and the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security buy this material from Acxiom.

Also in May, the FBI issued full-color “Most Wanted” posters for five Chinese nationals, members of the People’s Liberation Army, who had been indicted by a federal prosecutor for breaking into the computer systems of American companies and stealing trade secrets. If this was meant to kick-start negotiations with the Chinese on corporate spying, it failed miserably, since the Chinese immediately remonstrated, citing the United States’ own economic espionage activities. “For a long time, American authorities have conducted large-scale, organized cyber-theft and cyber-espionage activities against foreign dignitaries, companies and individuals,” the Chinese spokesperson Qin Gang said within hours of the indictments. “This is already common knowledge.”

He could have been referring to a widely circulated slide in Greenwald’s book titled “Serving Our Customers,” which shows that the NSA engages in spying at the behest of the US trade representative, as well as the Departments of Agriculture, Energy, and Commerce. Greenwald also presents evidence that the NSA was snooping on foreign energy companies, trade associations, and climate negotiators. Other Snowden material shows that the NSA had infiltrated the Chinese electronics company Huawei and stolen the source code for particular products.

Soon after the indictments, the Chinese withdrew from the China–US Cyber Working Group. Here, ironically, was the first clear demonstration that the Snowden–Greenwald collaboration was doing what former NSA director Keith Alexander said it would do back in March—“slowed the effort to protect the country against cyber attacks on Wall Street and other civilian targets.”

When Glenn Greenwald was first in touch with Edward Snowden, Snowden ex- pressed the fear that the information he sought to bring to light would be met with yawns. That, clearly, did not happen. There have been the pointed arguments about Snowden’s disloyalty and cowardice, Greenwald’s censoriousness, and their joint culpability. Lost, sometimes, in these accusations has been the fact that while American democracy may not be as robust as many thought it was before the Snowden revelations, they elicited the most basic democratic response—a debate about the reach and limits of government surveillance in the Internet age.

Though it is too early to know if any of the proposed reforms will be meaningful, and history bends toward cynicism, the need for radical change, at least, has been made clear in many forums, including the President’s Review Group. Why this matters was put most succinctly in the group’s report:

We cannot discount the risk, in light of the lessons of our own history, that at some point in the future, high-level government officials will decide that this massive database of extraordinarily sensitive private information is there for the plucking. Americans must never make the mistake of wholly “trusting” our public officials.

In that regard, the president’s men could not agree more with Glenn Greenwald and Edward Snowden.

-

1

More than 4.9 million people have some form of government security clearance, and about 1.4 million of those have “top secret” clearance. See John Bacon and William M. Welch, “Security Clearances Held by Millions of Americans,” USA Today, June 10, 2013. ↩

-

2

Neither won outright for his reporting. Rather, the Pulitzer committee awarded the prize for public service reporting jointly to The Guardian (American edition) and The Washington Post for publishing their stories. ↩

-

3

It should be noted that Greenwald’s complaints are not without merit. At the urging of the White House, the New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller held back for a year a lengthy story by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau on President Bush’s secret authorization of domestic eavesdropping, putting it in the paper only when his hand was forced by the impending publication of Risen’s book State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration (Free Press, 2006). At the Los Angeles Times, then editor Dean Baquet, again at the request of the government, refused to publish a story about the secret rooms installed by the NSA at AT&T and other telecommunications companies to monitor phone calls. Baquet is now executive editor of The New York Times. ↩