It is a rare event for an art museum to do a large and ambitious exhibition about a person who was not a visual artist. But then Kenneth Clark, the subject of such a show now at Tate Britain, was for some five decades a unique figure in the cultural life of his country. There have probably been few people in any country with so illustrious a record of analyzing, celebrating, and ministering to artworks and their creators.

Clark was essentially a writer, and his book-length studies and essays form a considerable and often scintillating whole. But his endeavors apart from his writing were remarkable in themselves, and at times the Clark who wrote and Clark the public figure can seem, for good and for ill, to be one and the same. Beginning in 1934, when he was thirty, and for the next eleven years, he was the director of London’s National Gallery. (He had already been the Keeper of the Department of Fine Art at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.) The youngest person to have been made the gallery’s head, he modernized it and, more famously, in the early days of World War II, shepherded its phenomenal collection to safety outside London, ultimately getting it to caves that were part of an abandoned slate quarry in North Wales. During the war, he helped to make the otherwise empty gallery, through lunchtime concerts and temporary exhibitions of all sorts, into practically the center of the city’s cultural life.

Meanwhile he was operating simultaneously as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures. It was a job he didn’t want but that, as he amusingly describes it, George V, on the first visit any reigning British monarch had made to the National Gallery, insisted that he take. Involved with filmmaking for the Ministry of Information during the war, Clark went on, after it, to be something of a television executive, all the while working as an arts administrator and ultimately serving as the chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain. He was a vigorous patron of artists, and he seems always to have been giving lectures. In different years he held the prestigious Slade Professorship at Oxford, and he presented significant lecture series at, among other places, Yale and Washington’s National Gallery.

Beginning in the late 1950s, he became a performer of sorts on British TV, where he would talk informally about, say, “What is good taste?” or spar with John Berger on Picasso, or introduce his TV audience to Chartres or palace gardens in Japan. His most spectacular television event was Civilisation, a thirteen-part series, from 1969, that charted developments in thinking, attitudes about society, and artistic accomplishment in Western Europe from the time of the fall of Rome on. Especially in the United States, where the book of the show sold over a million copies, it made him a kind of media star.

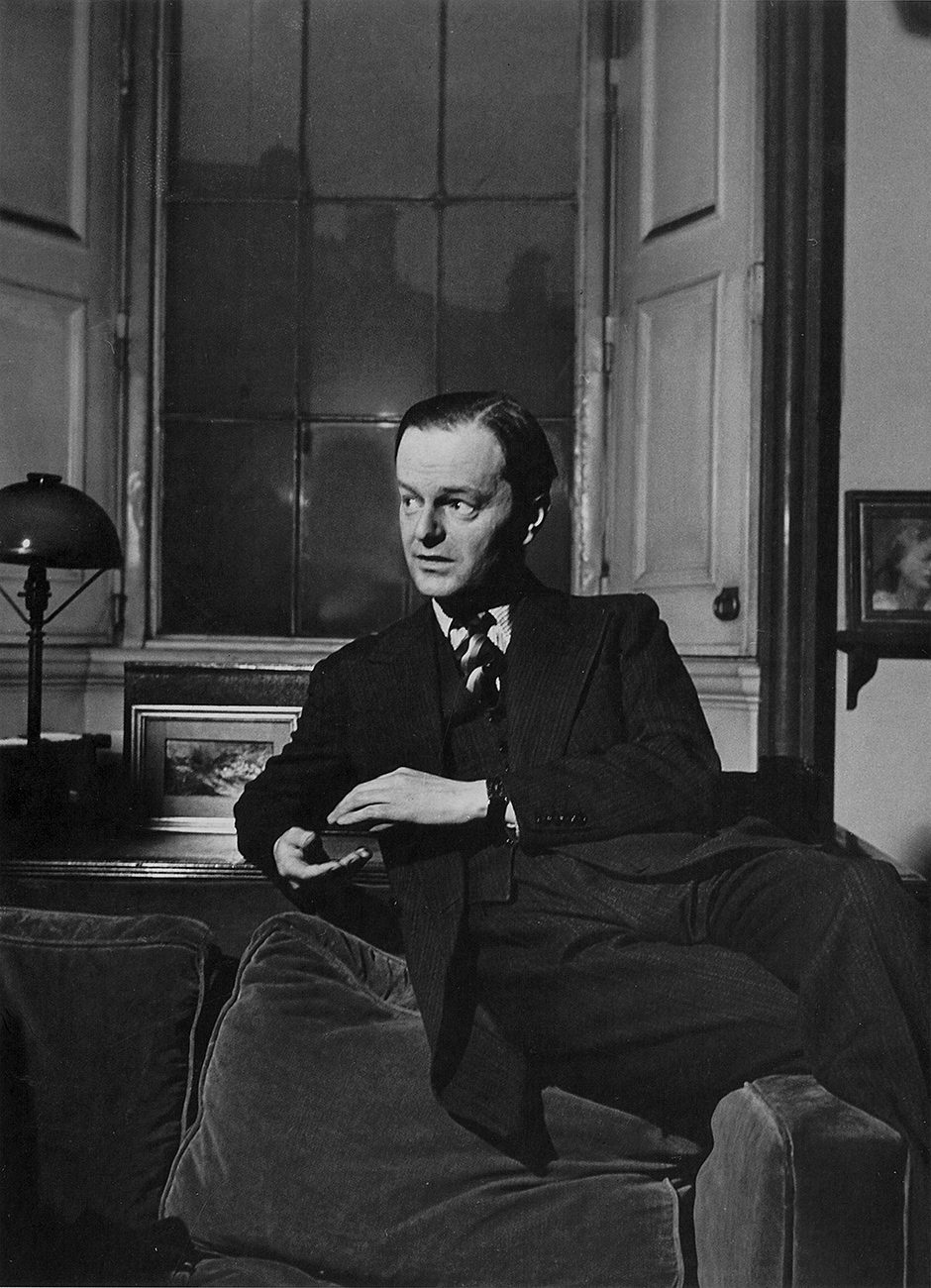

Clark, who went on to other TV series and continued to write all through the 1970s—producing along the way two lively and detail-packed autobiographies, Another Part of the Wood and The Other Half—was clearly a dynamic, even a driven, figure. (He died in 1983, at seventy-nine.) But reading him or watching him on TV, one rarely thought about his energy or ambition. What his audience encountered, rather, was a poised, rather reserved, somewhat patrician and superior person who, in a further twist, was also surprisingly tentative, tender, funny, and down to earth.

Grasping the full range of Clark’s writing may understandably take some doing. He was nominally an art historian, and he became one, in the late 1920s, long before, at least in England, the history of art was thought of as an autonomous field of study. It was what a small number of historians (of not necessarily art per se) or of research-hungry connoisseurs wanted to make of it. Many of Clark’s books, in fact, broke new ground. His 1939 Leonardo da Vinci was apparently the first work to take into consideration at the same time both the art of this Renaissance painter and the notebooks he filled with often abstruse speculations about math and science. Clark’s Piero della Francesca, of 1951, was (it is hard to believe) the first book of any depth on the artist in English. It is even stranger to learn that The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, of 1956, was the first survey of the subject ever undertaken. For it, Clark broadened his terrain to include classical Greek and Roman art, and he wrote as well at different times on Rembrandt, on Baroque art and architecture, and on French and English art from the Romantic period through the nineteenth century.

Clark understood, however, that his writing was really a personal blend of history and criticism. Meryle Secrest, in Kenneth Clark: A Biography (1986), notes that when he had to indicate his occupation on his marriage certificate (in 1927, when he was twenty-three), he wrote “art critic,” though at the time he hadn’t published anything. And it is his critical awarenesses, which suffuse his immense if lightly worn learning, that give his writing much of its continuing life. Even where his approach has dated, which is especially the case in his pages on nineteenth-century art, we want to know what his opinions are, especially as there is such an uncommon physicality and immediacy to his responses. It is nowadays rare, and a relief, to hear a historian and critic tell us when some artwork or style is “disgusting,” “revolting,” or (my favorite) “repulsive.”

Advertisement

We hear about Turner that “his figures, although not insignificant, are ridiculous,” and that the Gothic woodcarvers had “an almost irritating skill of hand.” We can smile in agreement when he refers to “one of those haunting pieces of nonsense with which Blake’s writings abound.” Clark had precise opinions even about matters that one would think were outside his ken. In a speech delivered in Washington he referred to Emerson as “your great underrated poet”—an unusual judgment (Emerson’s poetry is not what we tend to value him for) that· has the effect of opening up a new terrain before us.

It isn’t only Clark’s critical verdicts, though, that draw us on. It is the combination of his unruffled lucidity, his conversational rhythms (nearly all his works began as lectures), and his moments of sly joking—and his way of threading real-life concerns into recondite matters—that make his writing distinctive. He had a special feeling for plain, commonsensical words. When he says that “painting and literature depend largely on unpredictable individuals,” the words “depend” and “unpredictable” make a not-so-new thought seem alive.

His smallest comments can feel all-inclusive, even definitive. We hear, for example, that Leonardo’s concern was the “problem of pent-up energy.” Watteau’s subject was “make-believe.” The figures in Breughel’s pictures, he writes, are less people than “part of the mechanism of the universe.” Periodically he is simply dazzling, as when we read: “Myths do not die suddenly. They pass through a long period of respectable retirement, decorating the background of the imagination.”

Clark frequently calls himself, in his autobiographies, an “aesthete,” and he emphasizes that his true interest is not in theories about art but in what he can “enjoy” and in the palpable, physical object before him. Yet he also believed, as he wrote in Looking at Pictures (1960), that “art must do something more than give pleasure.” The tension in his work and perhaps in his life stems from this thought—from the way his sensuous and instinctive rapport with artworks interacted with his (perhaps conscience-fueled) need to make of his connection with art something more than so much appreciation.

He resolved the tension to some degree by being (as he called himself) a “public servant” and, from his early thirties already, a popularizer. Penelope Curtis, the director of Tate Britain and the person who proposed the idea of a show about Clark, refers in its catalog, with precisely the right words, to his “fearless popularisation.” Clark didn’t simplify the works he analyzed; but he never camouflaged his concern to mediate between artworks and artists and, on the other hand, what he called the “average man” or the “ordinary person.”

Yet his belief that art must give more than pleasure resulted in a proclivity for finding overly grand meanings to cover what sometimes were simply matters of taste. His belief may have encouraged, too, a rigidity about what art mattered and what did not. It is not that there is anything wrong in dwelling as he does on the greatness of Michelangelo, Raphael, Rembrandt, Poussin, Goya, and so forth. Besides, Clark touched, often sensitively, on many less-well-known figures. But his writing in a larger sense is marked by a kind of gatekeeper’s conviction that only the artists approved by consensus over time really count. Of a piece with the Clark who writes to keep the house of art in order is the Clark who all too frequently waves away this or that “mediocrity.”

Clark gave Civilisation the subtitle A Personal View, and his autobiographies in particular are bursting with minute, personal information. Going through his principal books about art, however, it is the personal—the wayward, let alone the outlandish—that we come to crave. Often it is not the subtly brilliant writer we hear—the Clark who could say that the sixteenth-century painter Correggio invented “prettiness”—but, rather, the director of a museum or the chairman of an arts council.

Tate Britain’s idea of doing a show about Kenneth Clark makes wonderful sense if only as a way to put his name back in circulation. Most of his books are out of print and my hunch is that most people under sixty, even in England, have little idea who he is. (Americans over sixty, when asked if they have heard of him, generally respond, hopefully, “civilization?”) The Tate show, organized by Chris Stephens and John-Paul Stonard, presents paintings, photographs, drawings, sculptures, and works in porcelain and majolica associated with different phases of Clark’s life. It ends with a room where we can see excerpts from the Civilisation TV series and from a number of his earlier broadcasts, which are in black and white and are, as TV shows, eye-catchingly primitive.

Advertisement

Clark came from a Scottish family whose notable affluence was based on cotton thread manufacturing. The show begins with some of the pictures he knew in his family’s house (he was an only child) when he was growing up. His father, who was principally involved in sporting pursuits (and gambling and drinking), enjoyed collecting pictures and hobnobbing with artists, and he was sorry when his son decided not to be an artist. The Tate’s exhibition expands with drawings by Leonardo from the Royal Collection (which Clark catalogued) and with pictures, including an excitingly colored and designed Virgin and Child with Angels, attributed to Benozzo Gozzoli, from around 1450, that are connected to Clark’s days at the National Gallery.

A highlight of the show is the room containing many of the objects that Clark and his wife Jane collected. They were impulse collectors. They bought amazing works, it is true, but also works that momentarily caught their fancy and objects that mostly had some bearing on his writing. What we look at, in other words, is a glorified version of the no-rhyme-or-reason kind of assemblage that artists or critics, or curators when buying for themselves, often put together. Seeing the works, and seeing, in photos in the show’s nicely designed catalog, how they were installed in the different houses that the couple and their three children lived in over the years, bring us almost as close to Clark as watching him on television.

Some of the Clarks’ grandest items couldn’t make it to the Tate (but are reproduced in the catalog). They are a Renoir of a lavishly round-bottomed female nude (Renoir’s wife), one of Zurbarán’s chaste still lifes, and a classic late Turner of very rough weather. In their absence pride of place, I think, goes to two magnificent Seurat landscapes (one now owned by the Tate, the other by the Metropolitan Museum). The work I would have taken, however, is a portrait by Joshua Reynolds of a young woman (who has been identified as two different people) from the 1750s.

Reynolds apparently only did her face, which he has made remarkably beautiful, and the brooch on her chest, leaving the rest to be filled in by assistants. The portrait wasn’t filled in, however, and seems all the finer for it. Knowing that the painting was previously owned by John Ruskin makes it a little spellbinding. For Clark, this nineteenth-century art and social critic was the “greatest member of my profession.” He is the subject of Ruskin Today (1964), one of Clark’s finest books. It is something of a duet. It is an anthology of passages from an exquisite if not always coherent writer, interspersed with characteristically calm yet acute essays by Clark introducing each theme.

Where the Tate show breaks down are the rooms devoted to the British art of the 1930s and 1940s that was important to Clark at the time. There are far too many works on hand by the Bloomsbury artists (Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant), by the mistily soft Euston Road realists (Victor Pasmore was the strongest painter in the group), and by Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, and John Piper. Clark served as a patron and promoter of nearly all of these, and he worked to get them and other British artists to record aspects of the national scene (which we also see) before they might be destroyed by German bombing.

Sutherland, Piper, Moore, and Pasmore are all artists of substance, and there are on view some fine examples of their work, along with a powerful picture of the war in the air by Paul Nash. But at least as displayed here, these British artists in general blend together. A viewer is left with an overall sense of muted color and an emphasis on black lines and craggy and torn shapes. In these ultimately dispiriting rooms, one forgets that the show is about Clark. In his autobiographies, as it turns out, these artists, while described fondly, are no more than a small part of the parade of people—whether actors, composers, royals, teachers, politicians, collectors, movie and TV personalities, museum employees, or scholars—Clark wanted to remember.

In Ruskin Today, Clark asked if it were “possible to find anything that can be called a theory of art” in the Victorian writer’s work. His answer was no, and that might be the case for Clark as well. In the words he uses about Ruskin, he, too, is more “poet” than “philosopher.” But there is a large drama played out in his thinking, and it stamps some of his stronger works.

One of his later (and less impressive) books, The Romantic Rebellion (1973), is subtitled Romantic versus Classic Art, and Clark seems to have felt this distinction personally. The two outlooks represent, one feels, sides of himself. By temperament he was on the side of the classical artist. His natural affinity was with balance, reason, rules, orderliness—with the “proper,” as he calls it in describing a Seurat painting, and with what he elsewhere calls “lawful harmony.” But he could also be swept off his feet by artists for whom harmony and the proper are insufficient, and his most charged writing is about two of them, Michelangelo and Rembrandt.

The Nude is Clark’s foremost work about the classical spirit. It presents an enlivening way of thinking about the subject. Clark makes us understand that the Greek sculptors who in the fifth century BC presented the unclothed human body in a state of what he calls “ideal beauty” were in effect creating an idea, or an art form. A naked person, as Clark puts it in a loose and undoctrinaire way, implies realism, or a realistic rendering of what is before the artist’s eyes. The nude, however, is about a shape that is “perfected by the mind.” During the classical era of Greece and Rome and then from the Renaissance onward for a few centuries more, the nude was a thought—a given—that one painter and sculptor after another took possession of in a different way.

Clark thought The Nude, in which he looks at varying presentations of Venus, say, or Apollo, or the way northern or non-Mediterranean artists attempted the subject, was his best book. So does John-Paul Stonard, who has written a balanced and sensitive essay on it in The Books That Shaped Art History. Stonard shows where Clark’s thinking has in certain areas run afoul of later academic views and yet remains, in its presentation of the “legacy of Antiquity,” prescient and vital. The Nude is undeniably an achievement. Throughout its great length it presents solid historical information, crisp critical perceptions, and a number of down-to-earth Clarkisms, such as “on the whole there are more women whose bodies look like a potato than like the Knidian Aphrodite.”

But The Nude is too long and becomes numbing. After trying to digest the umpteenth Venus we realize that a book about the “search for finality of form” is itself a formless compilation. And while Clark may feel that one or another Venus is a carrier of some deep emotion, it is primarily when he deals with Michelangelo, who invested the nude with a powerful inner, psychological life, that we believe this. Clark answered The Nude himself in his 1966 Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance. It is about an essentially romantic artist who thought that artistic and social conventions were meant to be broken. As presented here, Rembrandt was devilishly happy to show women as potatoes.

The book might be Clark’s own intellectual self-portrait. Looking almost exclusively at the seemingly circumscribed topic of how the Dutch painter, especially as a collector and frequenter of auctions, absorbed various Italian artists, Clark presents someone who is bewitched by the grandeur, sensuousness, and formal rigor of Mediterranean, or classical, art. Yet he also needs in his work a human truth—an awareness of the everyday and the tragic—that the artists of the Mediterranean, inventors of the nude, cannot fathom. Clark was rarely as moving as in the passages here on Rembrandt’s feeling for Bible stories—on how he saw “the life around him as if it were part of the Old Testament.”

Even more than describing artistic temperaments, though, Clark was drawn to foregone or imperiled things that deserve another look. It may be surprising that Civilisation, which is about demonstrations of will, energy, and creative freedom in Western European life and thought—and is not a history of art masterpieces—is also about an endangered idea. Clark begins by telling us that, whatever we mean by civilization, it was once, after barbarians overran Rome, entirely lost. He alludes to the thought—slightly echoing Cyril Connolly in The Unquiet Grave—that it was almost lost again during modern Europe’s two devastating world wars. That threat was real for Clark. On two occasions during the bombing of London he barely escaped with his life.

And another, less definable sense of loss may have hung over him personally. It is noteworthy that, while thoroughly immersed in the life of artworks and in the art scene of his day, Clark wasn’t seriously engaged by the art of his own time. He might use the word “great” on the rare times he referred to Matisse or Picasso, and he once owned some of their work. He could acknowledge the talent of numerous twentieth-century artists, and not only the British ones seen in the Tate show. He especially admired Henry Moore’s drawings. But he thought abstract art had “the fatal defect of purity,” and he confessed to being “completely baffled” by current art. The last figures he genuinely grappled with were the French artists of the late nineteenth century. Civilisation essentially ends with them. Their work, though, was largely over by the time he was born.

If his inability to be imaginatively caught up in modern art weighed on Clark I have not seen evidence of it. Yet how could this situation not have been at times mystifying, even painful? How could this long-standing wariness about his contemporaries not have fed the note of drift and apprehension about the future that is heard in Civilisation?

The wonder is that there is so little that is sour or elegiac, and so much that is enlightening and fun, in his work. Even when he wasn’t writing about art, he could give issues a tangibility and a sense of being seen freshly. In Civilisation, we hear that for two thousand years, or before nature came to be admired for itself, “mountains had been considered simply a nuisance.” Talking about the struggle to get society to see the horrors of industrialism (and by extension slavery), he tells us, perhaps unexpectedly, that the “greatest civilising achievement of the nineteenth century” was “humanitarianism.” It did not exist earlier. He says, to take one more example, that in the last quarter of the eighteenth century “science was to some extent an after-dinner occupation, like playing the piano in the next century.” It is the flow of observations and opinions like these that make Clark invaluable and, maybe better, rereadable.