In her acknowledgments at the end of Stone Mattress, Margaret Atwood distinguishes between stories and tales, and explains that—as the collection’s subtitle suggests—the short fictions we have just read belong in the second category:

These nine tales owe a debt to tales through the ages. Calling a piece of short fiction a “tale” removes it at least slightly from the realm of mundane works and days, as it evokes the world of the folk tale, the wonder tale, and the long-ago teller of tales. We may safely assume that all tales are fiction, whereas a “story” might well be a true story about what we usually agree to call “real life,” as well as a short story that keeps within the boundaries of social realism. The Ancient Mariner tells a tale.

In fact Atwood’s description of her book seems only half accurate. The first three of these “tales” could easily pass for what she calls “stories”—and rather good ones. Moving from “Alphinland” to “Revenant” to “Dark Lady,” we remain firmly in “the realm of mundane works and days,” among a group of elderly and somewhat dithery Canadians who have inflicted considerable romantic suffering on one other in the distant past.

At the center of “Alphinland” is wispy Constance Starr, much diminished by mourning and age, whose newly dead husband’s voice, “slightly mocking…teasing, making light,” guides her through the simple but critical steps necessary to survive a treacherous ice storm. But Constance is not merely a disoriented widow. She is also the author of a successful, long-established fantasy series, “Alphinland”:

As a child she’d had fairytale books with pictures by Arthur Rackham and his peers—gnarled trees, trolls, mystic maidens with flowing robes, swords, baldrics, golden apples of the sun. So Alphinland was just a matter of expanding that landscape, altering the costumes, and making up the names.

Though Constance’s writing has earned her a lot of money, though she is studied by doctoral candidates and interviewed onstage at conventions whose attendees come dressed as characters from Star Trek, she has never been taken seriously by the artsy Toronto snobs among whom she spent her wild and passionate youth:

The poets and folksingers made fun of her Alphinland stories, naturally. Why not? She made fun of them herself. The subliterary fiction she was churning out was many decades away from being in any way respectable. There was a small group that confessed to reading The Lord of the Rings, though you had to justify it through an interest in Old Norse. But the poets considered Constance’s productions to be far below the Tolkien standard, which—to be fair—they were. They’d tease her by saying she was writing about garden gnomes, and she’d laugh and say yes, but today the gnomes had dug up their crock of golden coins and would buy them all a beer. They liked the free beer part of it.

As the ice storm rages outside, Constance remembers (and has an erotic dream about) one of those snobs: a poet named Gavin Putnam with whom she was deeply in love, whom she supported with the proceeds from the earliest iterations of Alphinland, and whom she left after finding him in her own bed with Marjorie, a wild-haired free spirit “given to vibrant African textiles wound around her waist, and to dangling handmade bead earrings, and to a braying guffaw that suggested a mule with bronchitis.”

In “Revenant,” we visit Gavin and his wife Reynolds, whom he suspects of being unfaithful:

Serves him right for marrying a youngster. Serves him right for marrying three of them in a row. Serves him right for marrying his graduate students. Serves him right for marrying a bossy, self-appointed custodian of his life and times. Serves him right for marrying.

Reynolds has arranged for Gavin to be interviewed by a worshipful student who is writing about his poetry and who (surprise) turns out to be a beautiful young woman. The resultant triangle (grand old man, long-suffering wife, sexy female acolyte) is a familiar configuration, but what sets this one apart is that the big blow-up, when it comes, is not so much about Gavin, his work, or his womanizing, but rather about how and where Gavin has appeared in Constance Starr’s series of fantasies. This severe blow to Gavin’s vanity will (as we later learn) hasten his demise.

The next installment in this trio of interrelated stories, “Dark Lady,” takes us into the home and the minds of an elderly twin sister and brother, Jorrie and Tin. Jorrie is none other than Marjorie the hippie slut who broke up Gavin and Constance. Tin is gay, a classicist, mildly unhappy but resigned to his role as his sister’s keeper—and walker. He not only supports her but advises her on what to wear (no bright pink suit at a funeral, even if it is vintage Chanel!) and on how to color her hair:

Advertisement

At least he’s been able to stop her from dyeing it jet black: way too Undead with her present-day skin tone…. The hair compromise he finally agreed to is a white strip on the left side—geriatric punk, he’d whispered to himself—with, recently, the addition of an arresting scarlet patch. The total image is that of an alarmed skunk trapped in the floodlights after an encounter with a ketchup bottle.

Jorrie is a devoted reader of the local obituary column; her discovery of Gavin’s death notice alerts us to the chance that some of the poet’s wives and girlfriends will attend his memorial service. “Former lovers meet at the funeral” is a well-worn trope, but Atwood reanimates it by casting the frail, spacey Constance Starr as the celebrity among the mourners, while Jorrie is such a wreck that we find ourselves sharing her brother’s dread that she will find some way to embarrass herself.

The twins thoroughly enjoy the ironies of the excruciating service, which features the recitation of one of Gavin’s unfinished poems, a period of silent meditation “during which they’re all invited to close their eyes and reflect on their rich and rewarding friendship with their no longer present colleague and companion, and on what that friendship meant to them personally,” and a performance of “Mister Tambourine Man” by a wizened folksinger “with a straggling goatee that looks like the underside of a centipede.”

Afterward, Tin is detained in the men’s room by an acquaintance, a retired Princeton classics professor; Atwood cannily notes that Tin, unwilling to admit that he is at the funeral because his sister was briefly Gavin’s lover, lies about the reason for his presence there. By the time Tin breaks free and emerges from the washroom, he finds that Jorrie has managed to accomplish some version of what he has most feared from the start:

He should never have let her out of his sight! She’s gone to town with the sparkly metallic bronzer, and on top of that she’s applied something else: a coating of large, glittering, golden flakes. She looks like a sequined leather handbag…. Of course she hasn’t been able to take in the full effect of her applications in the washroom mirror: she wouldn’t have been wearing her reading glasses.

“What have you…” he begins. She shoots him a glare: Don’t you dare! She’s right: it’s too late now.

He grasps her elbow. “Forward the Light Brigade,” he says.

“What?”

“Let’s get a drink.”

Surely I am not the only reader who will find this moment more frightening than the scariest encounters with the vicious, gladiatorial Painballers and the genetically modified wild beasts—the pigoons and wolvogs—in Atwood’s most recent novels, the so-called MaddAddam trilogy.

The scale and ambition of Stone Mattress is limited, its tone delicate compared to the epic sweep of Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009) and MaddAddam (2013), narratives set in a world reduced by corporate greed and reckless scientific experimentation to a refuse dump littered with the detritus of civilization and populated by the bellicose veterans of a lethal combat sport. Yet though the body count in the new book is relatively low, though the violence inflicted here is more often (though not always) emotional rather than physical, the best of these fictions engage our interest and our emotions as strongly as the trilogy. Perhaps it’s because we recognize that we are likelier to experience something resembling the situations described in these understated stories than we are to find ourselves among the heroic survivors of planetary disaster.

The remaining pieces in the collection are more like tales in the sense that Atwood means: clever and witty but improbable, more interested in event than character, willing to trade plausibility for some startling plot turn or to arrive at a twisty conclusion. In “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a man bids on and wins the contents of a repossessed storage unit and finds himself the owner of a bridal gown, a wedding cake—and the grisly artifact that gives the tale its title. “Lusus Naturae” is told from the point of view of a woman whose physical deformity turns her into an outcast until she allows herself one moment of passion—a misstep that causes her neighbors to conclude that she is a vampire.

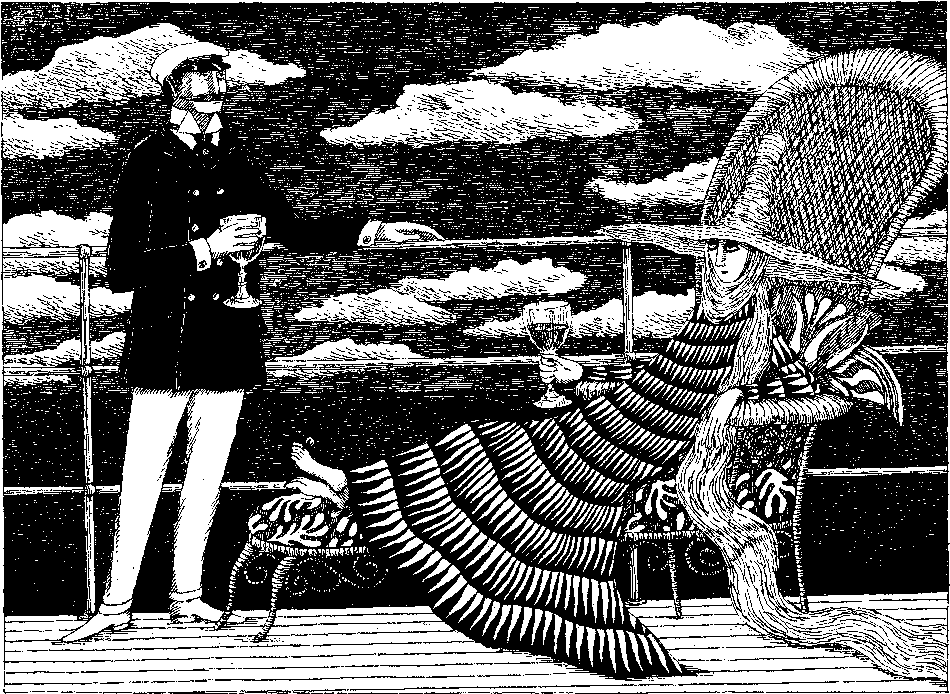

The problem is not that these fictions are implausible, but rather that they suggest missed opportunities for the writer to have done something more interesting. The gap between what we might have hoped for and what we are given is perhaps widest in the title tale, which takes place on a cruise ship of tourists bound for the Arctic. The setting may remind some readers of the brilliant Skating to Antarctica (1998), in which Jenny Diski seamlessly combined personal history and private obsession, telling portraits of other travelers, and eloquent descriptions of glacial vistas.

Advertisement

Atwood has something else in mind. One of her tourists is a woman who, as a teenager, suffered a traumatic assault from which she has never fully recovered. Now Verna recognizes her attacker—grown older and more wrinkled—among the men on board. What would one do, in the claustrophobic quarters of a boat headed for the Arctic, upon meeting the man who has ruined one’s life? In the very first sentence we are told, somewhat dismayingly, where this fictional voyage is heading: “At the outset Verna had not intended to kill anyone.”

In her acknowledgments, Atwood describes composing and reading “Stone Mattress” aloud to the great delight of her fellow passengers on a cruise ship to the Arctic. Perhaps one needs to have been there. Others may be disheartened to learn, so early on, that what we are about to discover is whether or not—and how—Verna takes her homicidal revenge on the man who wronged her. And if she succeeds, will she get away with murder?

Another tale, “The Dead Hand Loves You,” could have provided a fresh and thoughtful take on a situation that Atwood, the author of more than thirty books, presumably knows all too well: a writer bases a fictional character on a real person, or some aspect of that person. What happens when the model (or the presumptive model) confronts or merely resents the author of a book in which he believes he’s appeared? Such questions are very much at issue in “Revenant,” in which we watch Constance Starr admitting that the mythical figures in Alphinland are composites of people she’s met: “I sometimes take parts of them from here and there and put them together…Especially the villains.”

But “The Dead Hand Loves You” is more contrived—and content to remain on the surface. In his early twenties, Jack Dace—poor, desperate, sharing a house with friends who are usually drunk, stoned, or having a love affair with someone else’s lover—writes a cheesy horror novel entitled The Dead Hand Loves You and peoples it with barely disguised versions of his housemates. The book becomes a commercial hit and later a classic of the genre. Now, years after his only success, Jack sets out to track down his old friends, who are well aware of the uses to which he has put them in his lucrative work.

It’s an intriguing premise, but Atwood has made it less so by giving us too much summary of The Dead Hand Loves You and by adding a note of melodrama; the housemates had drawn up a contract agreeing to divide the proceeds from Jack’s as-yet-unwritten novel to compensate for his inability to pay his share of the rent. His friends assumed that he was never going to finish a book of any sort, so it was a bit of a joke. But their little game has had economic consequences, and over time the former roommates could become, if they want, the fortunate beneficiaries of Jack’s modest talent. Now Jack’s reason for ferreting out his friends is to kill the ones who insist on cutting into the profits that, he feels, should be his alone.

What makes this tale more involving than it might otherwise be is that, like the first three stories in Stone Mattress, it features an author of genre fiction who is commercially successful but not respected by “serious” readers and critics. This is clearly a subject of importance to Atwood, whose 2011 collection of nonfiction pieces, In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination, delineated the differences between the speculative fiction Atwood writes—dystopian novels such as The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and the MaddAddam trilogy—and the less literary genres of pulp fantasy and science fiction.

Like Constance Starr in “Alphinland,” Jack Dace enjoyed constructing imaginative scenarios for himself, and yet writes his novel for money; we have no sense that the act of writing has created for him, as it has for Constance, a portal into an invented universe into which the author can escape and find refuge, along with pleasures and rewards unavailable in the real world. Still, the presence of Jack Dace and Constance Starr within a single collection makes one realize how often writers populate their stories not just with bits of people they know but with the embodiments of their nightmares about how differently their lives might have gone.

A promising story that turns into a tale—in this case, a tale of ideas—is “Torching the Dusties.” An old woman, Wilma, nearly blind and living in an assisted care facility, is sensibly alarmed by the challenges and obstacles that sightlessness puts in her way. Yet she maintains her pluckiness and her sense of humor:

From the corners of her eyes she can still get a working impression, though the central void in her field of vision is expanding, as she’s been told it would. Too much golf without sunglasses, and then there was the sailing…but who knew anything then? The sun was supposed to be good for you. A healthy tan. They’d covered themselves in baby oil, fried themselves like pancakes. The dark, slick, fricasseed finish looked so good on the legs against white shorts.

Macular degeneration. Macular sounds so immoral, the opposite of immaculate. “I’m a degenerate,” she used to quip right after she’d received the diagnosis. So many brave jokes, once.

Wilma is buoyed by her friendship with another resident, an elderly gentleman named Tobias who seems to have borrowed his personal style from vintage films about gigolos working Viennese salons. Their relationship is satisfyingly complex, and we’re amused by Wilma’s intelligent ruminations about her friends, her grown children, and the fancy-dress parades of imaginary, miniature people who appear to her, a symptom of the Charles Bonnet syndrome, a pattern of visual hallucinations that can affect the blind:

A phalanx of little men forms up on the windowsill. No women this time, it’s more like a march-past. The society of the tiny folk is socially conservative: they don’t let women into their marches. Their clothing is still green, but a darker green, not so festive. Those in the front rows have practical metal helmets. In the ranks behind them the costumes are more ceremonial, with gold-hemmed capes and green fur hats. Will there be miniature horses later on in the parade? It’s been known to happen.

Once more, the world of the imagination is presented as a more colorful and entertaining alternative to the dull arena of “mundane works and days.” But before Wilma (and Atwood’s readers) have time to enjoy either her reality or her fantasies, she and her neighbors become the target of protest demonstrations and violent threats from an organization demanding that the old folks who have ruined the world step aside—die immediately and let the young have their turn. Burn the Dusties!

As in the MaddAddam trilogy and The Handmaid’s Tale, we note that the real aggressor is not a particular person, or a group of people, but rather an idea: here, it’s the view of the older generation as useless and redundant. Why not bypass politically awkward Social Security cuts (or their Canadian equivalent) and go directly to torching old-age homes and incinerating retirees?

Atwood is obviously right about a society’s view of the elderly and how they should be treated. And yet (as is often the problem with fiction that depends too heavily on ideas) our involvement with Wilma and her friends is dissipated rather than enhanced when she must escape from a band of shadowy figures whose ideology requires a crueler and more sudden end to her already truncated existence.

Some readers may admire these snappy tales and prefer them to the more naturalistic, skilled memento mori that begin Stone Mattress. And yet the book offers none of the peculiar comforts and reassurances of such post-apocalyptic novels as Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy. It denies us the glorious fantasy of flaming out en masse instead of, so much less dramatically, in a bed surrounded by a few grieving relatives; it withholds the consolation of leaving a ruined world—and being spared the certainty that life will go on without us, as if we had never existed. Also these stories lack the hopeful possibilities lurking within the dystopian novel’s cautionary subtext; since the horrors of the fictive future are usually the result of some existing practice or system, there’s always a chance that, perhaps inspired by the novelist’s warnings, we may yet mend our ways and avert the grisly future the writer has imagined for us.

Many of the men and women in Stone Mattress have made serious mistakes, but the repercussions are personal rather than global, and nothing—no eleventh-hour reversals in our headlong rush toward ecological catastrophe and mass extinction—could have prevented the loss of their youth, confidence, optimism, and health. The more effective stories in Stone Mattress may strike us as tougher in what they are willing to confront than the accounts of oppressive servitude—and more daring than the hellish odysseys—in Margaret Atwood’s apocalyptic fiction.

This Issue

September 25, 2014

The Cult of Jeff Koons

Obama & the Coming Election

Failure in Gaza