The news that Patrick Modiano had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature was greeted with jubilation in France. After all, the biggest best seller in the weeks following this year’s summer holidays—the great French rentrée—was Valérie Trierweiler’s unseemly personal account of the private life of the president of the Republic, François Hollande. So the idea that due recognition had been given to a writer distinguished by his subtlety and obsessed with the German occupation, a period that few Frenchmen are willing to face head on, an author with a virtuoso’s command of language, equally at ease with the simple and the complex, the precise and the evocative, restored a certain equilibrium. Modiano found the Swedish jury’s decision “bizarre,” but then Modiano tends to find everything bizarre and complicated, and he makes no secret of his distaste at finding himself in the spotlight of public attention.

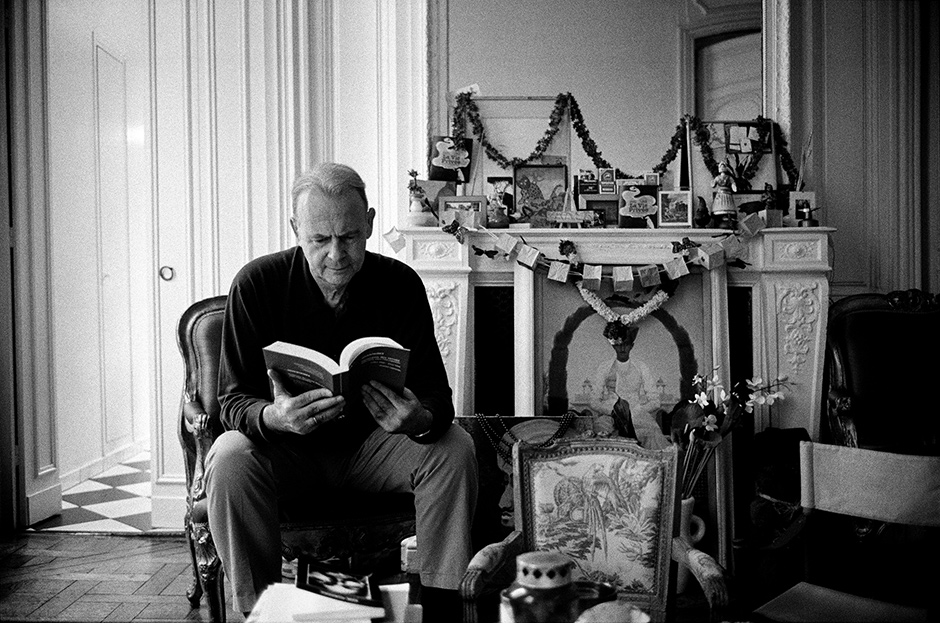

When Denis Cosnard, an economic journalist with a passion for Modiano’s work, decided to write his biography, Modiano’s publisher recommended he work alone. That was good advice, considering that Modiano refused to meet Cosnard. And it was probably for the best. To watch a video of Modiano being interviewed is to realize immediately that he is a journalist’s nightmare. Modiano clearly hates answering questions; he gets tangled up in his own sentences in which the word occurring most frequently is bizarre; he seems to be lost in a dense fog; he gestures wildly with his long arms as if they were the sails of a windmill; and by the time he has finished he hasn’t explained much. No doubt about it, Modiano is no talker, he is a writer.

He was born in 1945 (for nearly twenty years, he claimed he was born in 1947, the birth year of his younger brother, who died at the age of ten) in Boulogne-Billancourt, just outside of Paris. His parents met in 1942. His mother—“a pretty girl with an arid heart” according to her son—managed to leave her native Flanders in June 1942 through the protection of a German officer; she had landed minor film roles back home, and in Paris she worked for a German-run film production company. Modiano’s father was a Jew; his family, originally from Italy, had moved to Thessaloniki, but Modiano’s father was born in France. He never declared his Jewish identity during the war, surviving under a false name and making a living through shady means, all of them connected to the black market. Their son, Patrick, would spend the rest of his life obsessed with those troubled years, a dangerous time shrouded in lies. “That’s the soil—or the manure—from which I sprang.”

By and large, his parents ignored him. He was raised speaking Flemish by his maternal grandparents at least until the age of four. A few years later, he was placed in a series of boarding schools, from which he ran away repeatedly. “In the stretches of chaos that constituted my childhood and adolescence, years spent as a boarder, my only oxygen was reading.” In one Catholic boarding school, his French teacher noticed his literary sensibility and gave him special permission to read Madame Bovary while still in classe de seconde, the equivalent of tenth grade. He went on to read, helter-skelter, Proust, Pavese, Mauriac, Bernanos, and Wuthering Heights.

When he was fifteen, he became close to Raymond Queneau, a friend of his mother’s and a stunningly innovative novelist, very influential at the time. Queneau helped Modiano with geometry. “I myself understood none of it,” Modiano recalls. “He did his best to explain it to me. This was a year or two after the publication of Queneau’s best-selling novel, Zazie dans le Métro.He told me that he wrote the book on the basis of certain equations. I found that very hard to understand. He was quite taciturn.”1 Queneau continued to take an interest in Modiano and to encourage him.

Modiano’s parents lived apart, but in the same building. After passing his baccalauréat examination, Patrick lived in a room in his mother’s apartment. He enrolled at the university basically to avoid military service. His father showed no interest in him and once Modiano reached legal age he broke off all relations with him. Since his mother was away so much of the time, he was largely left to his own devices. Patrick lived by his wits, making ends meet by selling books, some of them stolen, and discovering the “singing Sixties.” He plunged into the music business and wrote fifty or so songs, including a hit for Françoise Hardy, who was already a very popular singer. At the same time, without a word to anyone, he wrote a novel and sent the manuscript to Queneau, who recommended it to Gallimard. In June 1967, Modiano learned that his book was accepted.

Advertisement

In the most autobiographical of his books, Un Pedigree, he wrote:

That night, I felt unburdened for the first time in my life. The menace that had weighed me down for all those years, forcing me to remain constantly on the alert, had dissipated into the Parisian air. I’d managed to get out into open water before the worm-eaten wharf could collapse entirely. It was high time.

This first book, La Place de l’étoile, marked the beginning of a long series. From then on, he would be a writer and nothing else. He was twenty-three years old. As an epigraph to his novel (whose title in French might equally refer to the Parisian square at the center of which stands the Arc de Triomphe or the location of the yellow Star of David that Jews were required to wear prominently during the Occupation) Modiano chose a Jewish joke to make sure no one misunderstood: “A German officer approached a young man and asked: ‘Excuse me, sir, where is the Place de l’Étoile?’ The young man pointed to the left side of his chest.”

La Place de l’étoile made quite a splash and won two prizes designed to encourage young authors, but it was not translated into English. It is a surprising book: not just provocative, but also disorienting. It sometimes feels as if it were spinning out of control. The story is so fast-moving, absurd, and hallucinatory, mixing real and fictional characters with such flair, that it is hard to follow, and yet it carries the reader along until, in the end, he finds the main character stretched out on the couch of a psychoanalyst whom he takes for Freud. The story told in a partly autobiographical style is that of Raphaël Schlemilovitch, a French Jew born just after the war, haunted by images of that war and by a persecution mania. A thousand contradictory identities coexist inside him: alternately, an anti-Semitic Jew, ultra-collaborationist, and also a vengeful wandering Jew, each of them pushed to the outer limit, unable to settle for being “just a Jew.”

It is a book intended to be outrageous but Modiano never stopped moderating its tone over the course of successive editions, a young man’s book in which one detects the influence of the two writers who influenced him most deeply: Céline and Proust. The verbal delirium is so clearly inspired by Céline that there are entire pages that are veritable pastiches of his work; Proust is not only quoted at length and caricatured as a snobbish, high-society Jew, but more importantly shares a dual identity with Modiano, that of a half-Jew, both Jew and non-Jew, an identity that torments him.

Is it possible to be at once a Jew and an anti-Semite? Proust was no stranger to this contradiction and he explored it with a certain cruelty in the character of Bloch. Modiano, torn asunder by a riven identity, said in an interview from that time:

Everywhere…I am the traitor…. When kids my age tell anti-Semitic jokes…I feel like killing them…and when I am with Jews…then I feel like insulting them…. It’s true that there are times when I am an anti-Semite…perhaps out of a yearning for putting down roots.

Modiano would never return to his tone of extreme provocation. The abscess had been lanced. He settled down to write thirty or so novels, the last of which, Pour que tu ne te perdes pas dans le quartier (“So you won’t get lost in the neighborhood”), came out this October. These were short novels—rarely longer than two hundred pages—often based on the same theme. Modiano’s predominant subject is the vile and cruel time of the Occupation. His characters develop in a society where the most sordid arrangements bring together Jews on the run, secret collaborators, crooks, Gestapo agents, impostors, and victims. None of the characters turn out to be what he or she seems to be at first and that gives these stories the allure of film noir, where the rising tension reels in the reader. It is often said that Modiano writes the same book over and over, and he himself explains why:

I often have the impression that the book I’ve just finished isn’t satisfied, that it rejects me because I haven’t successfully completed it. Because there is no going back, I’m forced to begin a new book, so that I can finally complete the previous one. And so I take certain scenes and develop them more fully. These repetitions have a hypnotic quality, like a litany. I don’t realize it when I’m writing, and I never reread my older books because that would throw me off…. You know, it’s hard to see clearly when it comes to things you’ve written. The repetition may stem from the fact that I’m troubled by a period of my life that resurfaces endlessly in my mind.

Two of his finest books happen to be among the very few available in English, and they are quite different from each other: Rue des Boutiques obscures and Dora Bruder.2 The main character of Rue des Boutiques obscures, an amnesiac detective, tries to find out who he is. He gathers enough evidence to identify himself as a man who might be him, and to imagine that the shock that made him lose his memory came from being abandoned in the snow by a smuggler who was supposed to guide him into Switzerland. In spite of a complicated plot, numerous gray areas, and a sense of vagueness shrouding certain characters, the book reads like a detective novel. And in fact, it not only won the Goncourt Prize in 1978 but also the Prix des Détectives.

Advertisement

Concerning this novel, Modiano remarks:

There also are snippets I associate with my parents, and with bizarre people they knew. It’s a book associated with the Occupation but not at all realistic. I used the names of actual people that I observed in my childhood, but I did so as if in a dream. I’ve always groped around the theme of amnesia, a theme explored in literature by Giraudoux and Anouilh, and which I found especially striking in American film noir. It was a film by [Joseph] Mankiewicz [Somewhere in the Night] that gave me the idea. And when I finished the book, it occurred to me that perhaps I should have treated it differently. That’s a theme that has always haunted me.

What Modiano calls snippets might be a name, a few dates, fragments that might suffice to evoke a life, in the absence of a complete biography.

As he was finishing that novel, a major publication reinforced his approach. Serge Klarsfeld published the first Mémorial de la déportation des Juifs de France, in which he catalogued the names of almost 80,000 victims, in a volume the size and format of a phone book. Modiano, overwhelmed by this publication, wrote Klarsfeld: “What is dreadful is to think of all that mass of suffering and all that martyred innocence leaving no traces behind. You, at least, have been able to track down their names.” Among those names was that of Dora Bruder.

Ten years later, Modiano, who liked to leaf through old newspapers and city directories, stumbled upon a classified ad published in the Paris-Soir of December 31, 1941: “Information sought about a young woman named Dora Bruder, aged 15, oval face, brownish gray eyes…. Please send any information to M. and Mme. Bruder, 41 Boulevard Ornano, Paris.” These few lines caught Modiano’s attention. Was it the name Dora, the same name as one of his father’s cousins—the sister of cousins murdered by the SS in Italy in September 1943? Was it the mention of a neighborhood in the northern part of Paris where he had lived on two separate occasions?

Whatever the case, he couldn’t stop thinking about it for months. He consulted the Mémorial and learned that Dora Bruder had been deported, like her father and mother, to Auschwitz. To find out more, Modiano contacted Klarsfeld, who obtained for him numerous photographs, the date and place of her birth, and a number of police files. Working with this scanty evidence, Modiano went on to write a book that would be published without any clear identification of its genre. Novel? Nonfiction? Documentary? The reader was free to choose. Klarsfeld, whom Modiano never mentioned in his text, opted for novel and wrote him:

[Your investigation] has more of the novel than it does of reality, because you leave me out entirely, even though God only knows how hard I worked to find and assemble the information about Dora and provide you with it…. Perhaps you are in love with Dora or her shade and, since we sought her together, you are just trying to keep her for yourself.

In the face of the insoluble problem of telling a story he was obsessed with but that could be based on only small fragments of information, Modiano chose to focus on his own search for the Bruders’ tracks, from the time they reached Paris from Central Europe until their departure, never to return. He did so by way of the episode that prompted the posting of that classified ad in Paris-Soir: the flight of Dora, an adolescent Jewish girl, in the heart of German Paris.

Who was Dora Bruder? What school did she attend? Why did she run away from home? How did she survive? And under what circumstances was she arrested and sent to the internment camp in Drancy? An array of questions that the author, like a detective, did his best to answer. A disappointing investigation, because what it turned up was largely a series of gaps that were impossible to fill in. “For lack of evidence, I’ve been obliged to embroider, to dilute the truth into a sort of soup,” he admitted in an interview.

In the end, it was the image of his father that emerged from the shadows. His father who, like Dora, had been pursued, who, like Dora, had been arrested by the police in 1942, but who, unlike her, had managed to escape. And the son’s attitude toward a father who never lavished care or affection on him, of whose past he’d always been ashamed, now softened. His father might have sullied himself with all kinds of trafficking, he might have associated with collaborationists, but wasn’t all that for the sake of survival?

Dora Bruder is the most painful of Modiano’s books, and not merely because the atrocious fate described in it is real but also because Modiano forces himself to reconsider the figure of his father, to reopen an old wound, to look straight in the face a

photograph that has been gnawed at by forgetfulness. It is forgetfulness that is the fundamental problem, not memory. You may have been very close to someone and, years later, that person appears to have been gnawed away at, with whole segments missing in your memory. It is the fragments of forgetfulness that most fascinate me. [For me] to write is to dream of being able to go back…. As if I could pass through the mirror of time and fix the past.

This fog that envelops people and places explains a lack of depth and individuality in Modiano’s characters. The author, and therefore the reader, are left on the outside, giving rise to the feeling that one is always rereading the same book. This is doubtless the reason why Modiano, in spite of his remarkable talent, and a success that has never flagged in the past forty years, has not acquired the indisputable stature of very great novelists. And so, when it was announced that he had received the Nobel Prize, certain French critics made no secret of their indignation or their surprise that once again Philip Roth had been passed over, even as they acknowledged the irresistible appeal of Modiano’s oeuvre, in which reticence contends with confession.

—Translated from the French by Antony Shugaar

-

1

Zazie dans le Métro is a novel written by Queneau in 1959. The plot is inconsequential: Zazie arrives in Paris by train, stays with her uncle, Gabriel, and departs from Paris thirty-six hours later. Zazie’s one goal before her arrival has been to ride the metro, but the metro is shut down because of a strike. It is the use of colloquial French, imaginative slang, surprising diction, inventive neologisms, and phonetic spelling that made it unforgettable. That season, to speak Zazie was all the rage in France. ↩

-

2

Missing Person, translated by Daniel Weissbort (London: Jonathan Cape, 1980; Godine, 2004); Dora Bruder, translated by Joanna Kilmartin (University of California, 2014). ↩