In response to:

Seduced by the Food on Your Plate from the December 18, 2014 issue

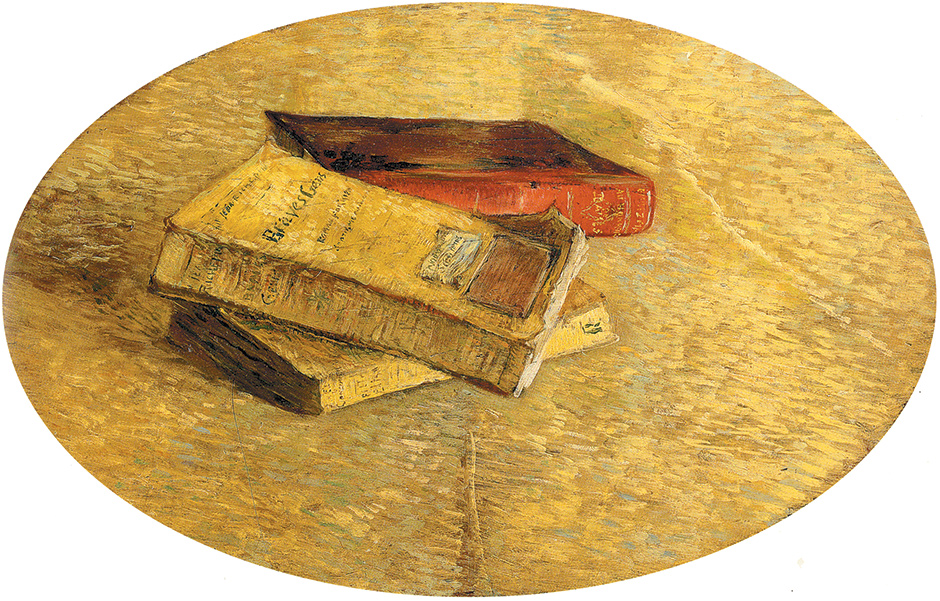

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Vincent van Gogh: Still Life with Books, 1887. See Michael Kimmelman’s review of

Julian Bell’s new biography of van Gogh in this issue.

To the Editors:

It is unusual, if not perverse, for a reviewer to devote more space to the topics a book does not discuss than to the actual substance of the work. Yet this is what Patricia Storace has done in her account of Sandra M. Gilbert’s The Culinary Imagination [NYR, December 18, 2014].

Patricia Storace overlooks lyrical meditations in Sandra Gilbert’s book on an overview of the role food plays in contemporary novels and poems. She omits any acknowledgment of a crucial section of the book: a long chapter in The Culinary Imagination on the urgent food politics that preoccupy so many of us today.

But she also egregiously misreads. When Ms. Storace attacks what Sandra Gilbert calls “TACT” (the “Tale of American Culinary Transformation”), she fails to note that in The Culinary Imagination Sandra Gilbert is telling this story ironically.

The weirdest and most disturbing aspect of Patricia Storace’s review is her emphasis not on the compelling book Sandra Gilbert wrote but rather on the book Patricia Storace thinks Sandra Gilbert should have written. Worse still, starting with Patricia Storace’s discussion of the memoirist Zhang Dai and then focusing on the poetry of Robert Burns, this reviewer seems to want to review a book that she would have liked to produce.

The result is patronizing to the extreme. Is Patricia Storace really going to instruct a pioneering feminist critic on the gender politics of food writing—as she seems to do when discussing Charles Dickens and his wife—or the racial dynamics of the post–Civil War South? What an offensive tone to take with one of America’s finest literary critics.

Susan Gubar

Indiana University

Elizabeth Abel

University of California, Berkeley

Ben H. Bagdikian

University of California, Berkeley

Marlene Griffith Bagdikian

University of California, Berkeley

Martin Davis

New York University

Martin Friedman

CSU East Bay

Max Paul Friedman

American University

Ruth Rosen

University of California, Davis

Patricia Storace replies:

In my review of Sandra Gilbert’s The Culinary Imagination, I did not overlook the author’s “lyrical meditations,” but warmly appreciated them in the early paragraphs of my essay, accurately describing the book as not a wide-ranging or comprehensive exploration of the culinary imagination, but a personal and intellectual cabinet of treasures.

Nor did I overlook the author’s diffuse chapter on food politics; its gaps in providing historical and social detail that would illuminate the subject of contemporary food politics for readers were a persistent characteristic of the book’s treatment of other topics. Events that the author does not explore, like the United States Army beef scandals of the Spanish-American War and the struggles of Harvey W. Wiley, Alice Lakey, and many other campaigning women to establish the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 in the face of fierce opposition from the food lobbies of their day form a kind of biography of our current situation. They are supremely relevant to the issues we face today, not only in the United States, but also worldwide. Without being given a fuller picture of our modern food politics in relation to the not very distant past, we risk drawing premature conclusions. A meaningful discussion of these issues was not possible given the constraints of space, and might have distracted the reader from more central literary and cultural themes of the book.

When an author writes that few bourgeois families in 1950s America could “boast of cooks,” it would be irresponsible not to acknowledge the legions of black and Latina domestics of that period, and decades before and beyond, who are represented by a wide range of novelists, from Fannie Hurst to Larry McMurtry to Kathryn Stockett. To mention their existence is not to patronize, attack, or instruct the author on racial dynamics, but to respect the truth of history.

As to Robert Burns as an important conduit of the poetry of common life in American literature, I defer to Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose insight it is.

In a book with a title like The Culinary Imagination, it is reasonable to expect some recognition of a figure emblematic of sublime culinary imagination, like Zhang Dai, just as it would be reasonable in a book called The Religious Imagination to expect some treatment of Jesus Christ.