1.

The opening verses of “Tangled Up in Blue” are among the most famous in Bob Dylan’s repertoire. Readers who know them will find themselves singing along: “Early one morning the sun was shining, I was laying in bed/Wondering if she’d changed at all, If her hair was still red.” Pronouns matter in Dylan, especially his “I” and “you,” whose limitless friction, wearing each other away year after year, Dylan’s songs have often so beautifully expressed. But there’s no “you” in “Tangled Up in Blue,” which is, in a way, the point: the unnamed “she” is lost, out of earshot, beyond conjuring, a creature who haunts Dylan’s dreams.

Otherwise these pronouns have been treated, over the years, as though they were interchangeable: the “I” has frequently turned into a “he,” and, at least once—in a performance from 1975 captured on The Bootleg Series, Volume V—a “she,” “wondering” about her own changes as well as, weirdly, the color of her own hair (“Early one morning the sun was shining, she was laying in bed,/Wondering if she’d changed at all, if her hair was still red”). One minute Dylan is building his usual fortifications around an “I” whose position he appears ready to defend unto the death; the next, he transfers all that subjectivity into another vessel. The emotions have been leached somehow from lover to beloved, from self to stranger, from hero to antagonist.

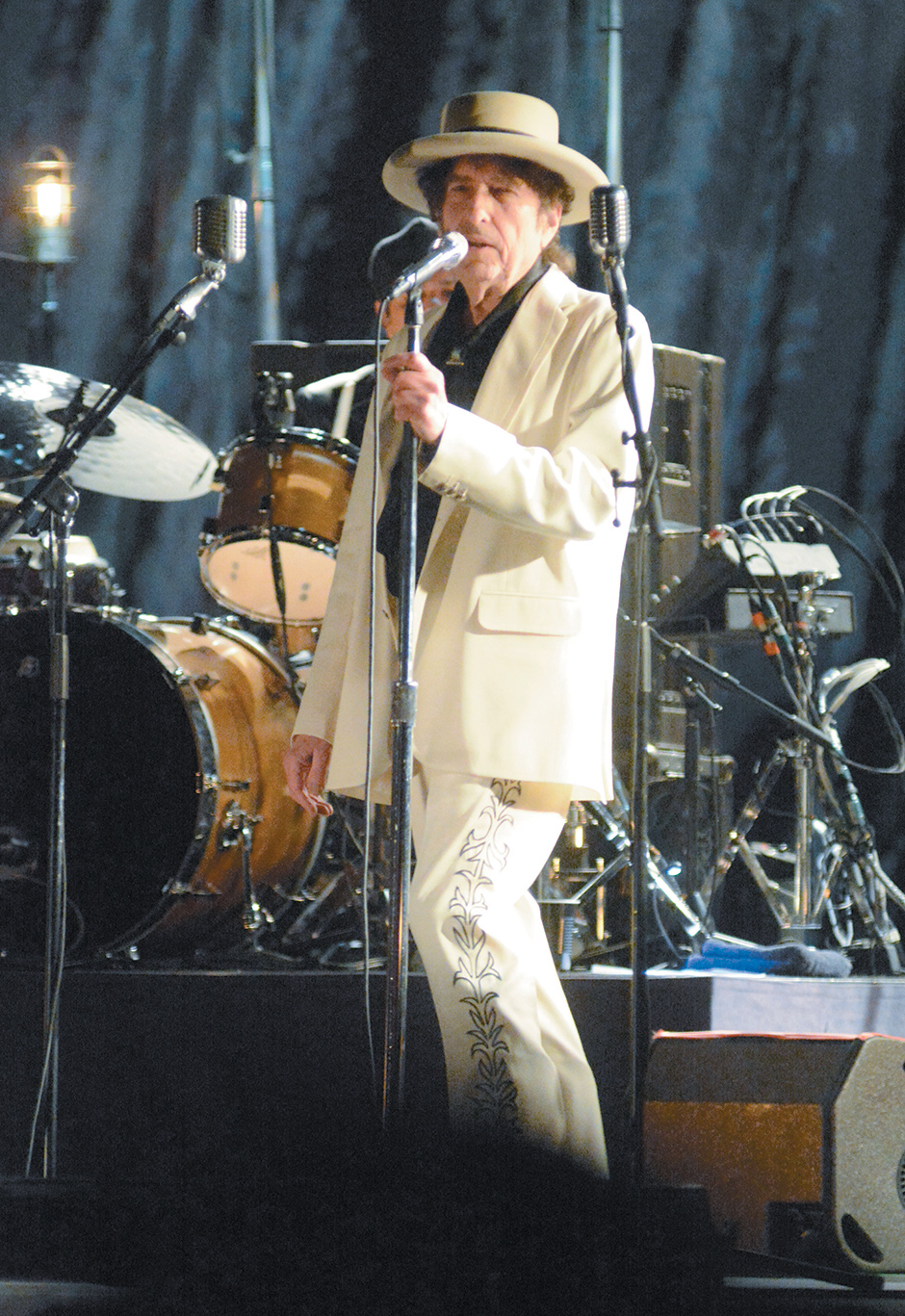

“Tangled Up in Blue” is considered an autobiographical song, the biggest hit from Dylan’s most candid album, his “divorce album,” 1975’s Blood on the Tracks. It is among only a handful of his older songs that he still plays in concert, though on a recent evening at the Beacon Theatre in Manhattan it had been rendered lyrically unintelligible and melodically alien. A song I’ve sung along to countless times, which taught me about heartbreak before I’d suffered any, sung by Dylan, now seventy- three, not thirty feet from where I sat, was unrecognizable through half its length.

It was the 1,400th or so time Dylan had performed the song live, according to BobDylan.com, which keeps meticulous record of such things. You could see people in the seats around me latching onto a phrase, any phrase, they recognized—for me it was “point of view”—and jumping in eagerly to harmonize, only to have those small holds disintegrate inside their grasp.

Dylan has treated his songs, from the start, almost like a Mad Libs game, swapping out one lyric for another, switching emotional teams, altering his arrangements so as nearly to undermine the meaning of the original song. At the Beacon, Dylan did a rather louche “Blowin’ in the Wind” as an encore (his encores, like his set lists as a whole, are almost entirely standardized these days; most everyone in the audience knew the song was coming next). It was a raw and rainy night in New York, and earlier that afternoon the grand jury in the Eric Garner case had announced its decision not to indict the police officer who had held Garner in a chokehold, leading to his death. Inside, Dylan sang the old protest song while seated at the piano; the prosperous-looking men and women of the audience, in quilted jackets and massive gray hair helmets, were jockeying to get closer to the stage. Many people snapped pictures on their smartphones, turning the physical presence of the legendary man back into an image, as though he became somehow more real when transformed into electronic bits.

Two guys in their sixties, looking like they’d flown in on a Gulfstream, lit up a joint, only to be immediately scolded by security. My sympathies went to the security guard, a black man in his twenties; what would have seemed a countercultural gesture, once upon a time, now seemed like an assertion of privilege. I was hoping these fools would be kicked out. Such ironies were there to be exposed, though Dylan, who has battled with audiences often in his career, glided above them. In his bolo tie and white coat, he looked like a character from one of his songs: a Wild West dandy, perhaps a frontier barrister or bondsman. The “I” had again ducked behind a “he”: a character, a persona.

It is cliché to say that Dylan’s nature is change. “He’s changed altogether,” remarks a heartbroken British fan leaving one of his first electric shows, in a clip from Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home (2005), before providing this helpful gloss on the word “change”: “He’s not the same as what he was at first.” And yet the “real” Dylan has been popping up in odd places of late. In 2009, police in Long Branch, New Jersey, were alerted to the presence of an “eccentric-looking old man” wandering around a residential neighborhood in the rain and peering into the windows of a house marked with a “for sale” sign. When the police arrived, the man introduced himself as Bob Dylan. He had no identification; the officer, Kristie Buble, then twenty-four, suspected he was an escaped mental patient. It “never crossed my mind,” she said, “that this could really be him.”

Advertisement

Dylan politely explained that he was on tour with Willie Nelson, playing a nearby resort. He was taken in the patrol car back to the hotel, where his manager identified him. Dylan was exceedingly “nice” throughout the ordeal, the officer reported, noting his odd request that, once identified, she drive him back to the neighborhood where he’d been picked up. She had interrupted him doing god knows what; she was his Person from Porlock.

He has a habit of showing up at the childhood homes of fellow musical legends. The Long Branch neighborhood wasn’t far from a house where Bruce Springsteen had lived while writing Born to Run. In 2008, Dylan and his manager were discovered standing on the front lawn of the home in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where Neil Young had lived as a teenager. The owners gave the men an informal tour, during which Dylan asked a number of “thoughtful questions.” In England a year or so later, Dylan slipped unnoticed into a public tour of John Lennon’s childhood home in Liverpool, where he “lingered” over photos and other artifacts, telling the house’s curator that Lennon’s “simple upbringing was similar to his own.” Standing next to Dylan in Lennon’s childhood bedroom was, the curator reported, “surreal.”

It is a commonplace to describe Dylan as mercurial, chameleonic, a “shape-changer” out of Irish mythology, as his friend the late Liam Clancy put it. And yet only one person on earth could have gotten out of the trouble in Long Branch by identifying himself as Bob Dylan. If anybody else had tried, the trouble would have been worse. The desire of others to be Dylan, though, is by now as canonical as Dylan’s opposing wish to be someone, anyone, else. The lyric from the 1993 Counting Crows hit “Mr. Jones,” its title lifted from “Ballad of a Thin Man,” comes to mind: “I want to be Bob Dylan.” The Beastie Boys sang of “chillin’ like Bob Dylan”; David Bowie, echoing Dylan’s “Song to Woody,” has his own “Song for Bob Dylan.” In their song “History Lesson, Part 2,” the 1980s West Coast punk band the Minutemen ranked Dylan, old enough to be their father, with punk legends like Richard Hell, Joe Strummer, and others.

With everyone wanting to be him, you might think Dylan would guard his identity more zealously. And yet he gives the impression, often, of being more than willing to hand it down, the way James Bond is handed down from one actor to another. In Dont Look Back, D.A. Pennebaker’s classic documentary about the 1965 England Tour, Dylan (who says he wants “a new Bob Dylan,” sick of the old one) can be seen squandering his Dylanness so profligately that he seems to want to spend it down out of spite, like some cursed inheritance.

The name was originally more or less meaningless: he was going to call himself “Robert Allen” (his given first and middle names), which sounded to him like “a Scottish king.” He then saw the name of a saxophonist, David Allyn, and decided he liked that spelling better. Though he preferred “Robert Allyn” to another name in contention, “Robert Dylan” (he seems to have had only a passing acquaintance with Dylan Thomas), he liked “Bob” and thought “Bob Allyn” sounded like a car dealer.

After he’d played around with it some more, voilà, “Bob Dylan” was born. Lately he has suggested that he is the “transfiguration” of a Hell’s Angel, “Bobby Zimmerman,” who died in a motorcycle accident in the early 1960s. Transfiguration, he remarked in his Rolling Stone interview from 2012, is a way of “crawl[ing] out from under the chaos” in order to “fly above it.” He seems to be quite serious about the notion that several of his old manifestations—beginning with his namesake Hell’s Angel whose motorcycle accident presaged Dylan’s own, near-fatal crash, in 1966—are in fact dead.

And yet he is obsessed with his origins. “Home” is perhaps the most important word in Dylan’s oeuvre. It appears in the first verse of his first important composition, “Song to Woody.” (“I’m out here a thousand miles from my home.”) We return home to gauge how far we’ve come, how much we’ve changed from what “we were at first.” Change enough, and you can return home as a stranger, even as an intruder; and yet the point in sneaking home in disguise is to be recognized by those who know you best, who see beneath the vagaries of appearance. (The literary parallels are not lost on Dylan, who has described his career in Homeric terms.)

Advertisement

Growing up in Hibbing, Minnesota, “Bobby” Zimmerman made it clear that he would leave as soon as he could. Highway 61 passes right through Duluth, where Zimmerman was born; it carried him swiftly away and into his first phase as a protest singer. Later, armed with a new name and a new sound, he “revisited” it so that he could mark a new departure on Highway 61 Revisited.

More than any musician of his era, Dylan seems to have vanished and reappeared inside his own art, making records that alternately mask and unmask his gift. I encountered Dylan’s classic recordings from the Sixties during the 1980s, a period when, as Joshua Clover has suggested, he all but “[unmade] his popular fame.” Records from this period, including Empire Burlesque and Knocked Out Loaded, to say nothing of the farcical Dylan & the Dead, suffer from Dylan’s characteristic overestimation of the minor talents with whom he collaborated, people like Ronnie Wood, Tom Petty, and Jerry Garcia. Like another figure of comparable genius and longevity, Jean-Luc Godard, he is sometimes suspected of self-sabotage, as though the dismantling of beauty were its ultimate manifestation.

He has returned, in the last two decades, “a prodigal,” as Clover put it, to a music older than the folk scene, a music that, since it was never fully metabolized by pop, seems new. His fixations are on brilliant display: the world of his childhood, of rural Minnesota, of the attenuated, lonely 1950s, “woods and sky and rivers and streams, winter and summer, spring, autumn.” We have never had a music like this, full, as Dylan has allowed, of “circuses and carnivals, preachers and barnstorming pilots, hillbilly shows and comedians, big bands and whatnot.”

Very few of his fans know these songs well, though critical praise has been lavish, especially for Tempest (2012), his last album before the just-released Shadows in the Night. At the Beacon, much of the crowd vanished after the first set; I saw Geraldo Rivera with a lady friend, making, it appeared, a beeline for the door. The silver-haired plutocrat in the row behind me, having ostentatiously brought to the show his young son, whom he plied with snacks and allowed to play with his phone, failed to return for round two. That stick insect onstage in the Samuel Clemens outfit was not the Dylan anybody had come to see.

And yet here he was, fifty years after he confounded the crowds at Newport and the Royal Albert Hall, still playing difficult new music in his own way. As so often with this performer, pleasure was synonymous with aversion overcome. The old Beacon Theatre, the vaudeville days still evident in its scale and décor, seemed revived by this strange visitation of a figure out of its own legend.

2.

Songs with this degree of plasticity, reshaped in performance when the conditions of performance themselves shift and change from night to night, season to season, year to year, would seem impossible to collect between covers. The Lyrics: Bob Dylan, edited by Christopher Ricks, Lisa Nemrow, and Julie Nemrow, is a grand hardcover edition of Dylan’s lyrics, weighing in at thirteen and a half pounds, measuring roughly thirteen inches square and more than three inches thick. It recalls those hulking medieval codices that were used as trays and cutting boards, or the kind of lap desk Robert Frost sometimes used to compose his poems. These days, though music has been liberated from the cumbersome world of material objects, many people, perhaps especially Dylan’s fans, retain a body memory of the feeling of holding in their laps a heavy stack of LPs. In those days, records often came with lyrics printed on the sleeve, as well as liner notes, a mature genre to themselves, now all but forgotten.

One’s encounter with music was often a literary experience, an experience of reading and listening simultaneously. It was by nature a comparative endeavor, with the printed words sometimes standing for, without standing in for, the lyrics as sung. The discrepancies between page and voice were meaningful, and it was the fan’s job to articulate those meanings. This book recreates something of the holiness of records, the care expected when we handle them, the occult significance of owning them, their transformative presence—beyond all but the most special books—in a room.

Of course Dylan’s lyrics sprawl unmanageably in every direction, and they’ll never be finished until after he’s dead. The original written version of every song since 1962 is printed here on the verso, with many important variants printed on the facing page, and others residing in appendices.

This format leaves acres of white space (though the pages are actually a pale yellow that suggests paper mellowed by age) for monastic jottings and rabbinical marginalia, though few who spend the money for this object will dare deface it with their own notes. Dylan, who I picture writing his lyrics on a portable typewriter, in a crowded hotel room, with a film crew rolling, with his entourage splayed across couches and floors, while drunk or high, in a hurry, would seem ill-suited to such a formal and definitive presentation of his words.

And yet there is something touching, even intimate, about reading these lyrics as poetry, a feeling of being alone with Dylan as no fan has been since his earliest concerts on MacDougal Street. His power, in his best songs and most astonishing performances, is to penetrate the layered distance implicit in his showmanship. His voice made it clear from the start that finding Dylan in the wilderness of his own self-presentation—ever changing, often defiantly strange or surprising—was the primary pleasure afforded by his art. Whatever else was costume on that stage, the voice (except for the brief period when, under the sway of Johnny Cash, he crooned) was not costume. His voice was a means of isolating his lyrical gifts, as was his countermelodic phrasing, insisting on the words over the tunes. Only when he wrote these songs was Dylan alone with himself, the totality of his isolation dramatized by the swirling, almost frighteningly populated environments in which he sometimes wrote.

But the words require arrangement, and often their arrangement on the page has little to do with the ways Dylan has arranged them musically. For example, we have no typographical equivalent for his remarkable harmonica passages, which often push us to the brink of impatience as we await the resumption of the song—and, often, the climax of the story. One thinks of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” when the harmonica, standing in for the judge’s deliberations after Dylan has made his “case” against the murderous aristocrat William Zantzinger, finally yields to the news of an appallingly light “six month sentence.” The regular intervals between stanzas can’t make the sound of a harmonica, nor can they create those variable intervals, here expanding, there collapsing, between verses when the instruments do their thing. But the page offers its own nontransferable pleasures. Here is the final verse of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”:

In the courtroom of honor the judge pounded his gavel

To show that all’s equal and that the courts are on the level

And that the strings in the books ain’t pulled and persuaded

And that even the nobles get properly handled

Once that the cops have chased after and caught ’em

And that the ladder of law has no top and no bottom

Stared at the person who killed for no reason

Who just happened to be feeling that way without warning

And he spoke through his cloak most deep and distinguished

And handed out strongly for penalty and repentance

William Zanzinger with a six-month sentence

Ah, but you who philosophize disgrace

And criticize all fears

Bury the rag deep in your face

For now’s the time for your tears

These lines are loosely anapestic, the unstressed syllables colliding into four strong stresses per line (“and he SPOKE through his CLOAK most DEEP and dis-TIN-guished”) until, in the refrain, the sentiments compress, the meter (in the third-to-last and final lines) becomes trimeter, and the rhymes turn emphatic, impossible to miss. This is the syntactical equivalent of judicial deliberation, and when the sentence settles on an object, the judge delivers his verdict.

The refrain changes the terms of address (confronting a callous, incrementalist “you”) and the scope of reference. There is no way to sing these verses so as to suggest how prominent the word “stared” is when it appears on the page, one of the few lines with a stress on the first syllable. And the musical outro, here missing, of course, somehow softens the rage; here the white space stands for an indignation so raw language can’t capture it.

Nobody before Ricks (who has been coy about how much help Dylan provided) has so meticulously and so brilliantly set these words in lines and stanzas, which remind us that some of the greatest lyric poems, from Shakespeare and Thomas Campion and George Herbert to the Child Ballads and beyond, are written accommodations of performance. Take the final two verses of one of Dylan’s greatest, and most literary, songs, “Desolation Row,” the final tune on Highway 61 Revisited. Sometimes I inflict upon my family a game, best played with Dylan’s music from this era, where we listen to a line from Dylan, I pause the song, and they have to fill in the rhyme. Such is the climate of impending surprise these songs provide, verse after verse, as the strangest and most affecting rhymes are chosen within a structure otherwise highly regular and predictable.

On the page, “Desolation Row” is much less a game of “wait for the rhyme,” with its serpentine twelve-line stanzas yielding, sometimes despite their own complexity, the same phrase every time:

Praise be to Nero’s Neptune

The Titanic sails at dawn

And everybody’s shouting

“Which Side Are You On?”

And Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody ever thinks too much

About Desolation Row.

Eliot and Pound are there partly to represent the grandiose spats of canonical literature, the rarified modernists turning Yeats’s “tower” (and Edmund Wilson’s, and, via “captain,” Whitman’s) into a farce. This explosive historicity, this gleaming modernism, ignores (as Eliot’s and Pound’s free verse could be said to ignore) the perpetual and the timeless: those calypso singers and mermaids. Dylan’s song borrows its associative vigor from Eliot and Pound, perhaps, but it finds in its own traditional verse forms a soundness, unbreachable and timeless. Here, as so often in his work, Dylan’s sung poetry stands for, and continues, the popular forms deemed unworthy of academic consideration. Thanks to Professor Ricks and this fine edition, nobody is going to make that mistake with Dylan.