In 1941, a Harvard University anthropology professor named Carleton S. Coon traveled to Morocco, ostensibly to carry out field research. His true mission was to smuggle weapons to anti-German rebels in the Atlas Mountains, on behalf of the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime precursor to the CIA. The following year, as the United States prepared to invade North Africa, Coon and an OSS colleague, Gordon Brown, drafted propaganda pamphlets intended to soften up local reaction to the coming swarms of GIs. They settled on a religious idiom: “Praise be unto the only God…. The American Holy Warriors have arrived…to fight the great Jihad of Freedom.” The pamphlet was signed “Roosevelt.”

Nazi Germany’s leaders also harbored half-baked ideas about messaging to North Africa’s Muslims. Heinrich Himmler was the Third Reich’s most influential advocate of the instrumental use of Islam in war strategy. In the spring of 1943, as Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s army in North Africa stumbled to defeat, Himmler asked the Reich Security Head Office “to find out which passages of the Qur’an provide Muslims with the basis for the opinion that the Führer has already been forecast in the Qur’an and that he has been authorized to complete the work of the Prophet.”

Ernst Kaltenbrunner of the Head Office replied with the disappointing news that the Koran had no suitable passages for such a claim, but he suggested that Hitler might be advertised as “the returned ‘Isa (Jesus), who is forecast in the Qur’an and who, similar to the figure of the Knight George, defeats the giant and Jew-King Dajjal at the end of the world.” Ultimately, the office printed one million copies of an Arabic-language pamphlet that sought to persuade Muslim Arabs to ally with Germany:

O Arabs, do you see that the time of the Dajjal has come? Do you recognize him, the fat, curly-haired Jew who deceives and rules the whole world and who steals the land of the Arabs?… O Arabs, do you know the servant of God? He [Hitler] has already appeared in the world and already turned his lance against the Dajjal and his allies…. He will kill the Dajjal, as it is written, destroy his places and cast his allies into hell.

Such propaganda “may seem absurd today,” writes David Motadel in his comprehensive and discerning history, Islam and Nazi Germany’s War. And yet one need only review the awkward, cartoonish texts of American propaganda pamphlets dropped on Afghanistan before the US-led invasion of that country in 2001 or the similarly naive pamphlets dropped on Iraq before the US-led invasion to oust Saddam Hussein in 2003 to recognize that the history of ill-considered Western hypotheses about how to mobilize or co-opt Muslim populations during expeditionary warfare is a long one.

The record of World War II is that the Allied and Axis powers both invested substantially in strategies to win over Muslims and that both succeeded only partially and temporarily. Even these limited achievements were informed by cynical expedience on the part of the invading European forces and the adapting Muslim populations in their way. For many Muslims living in the path of German, Italian, or British tank divisions, after all, the war was best understood as a conflict among colonial oppressors—a war best waited out, to the extent possible.

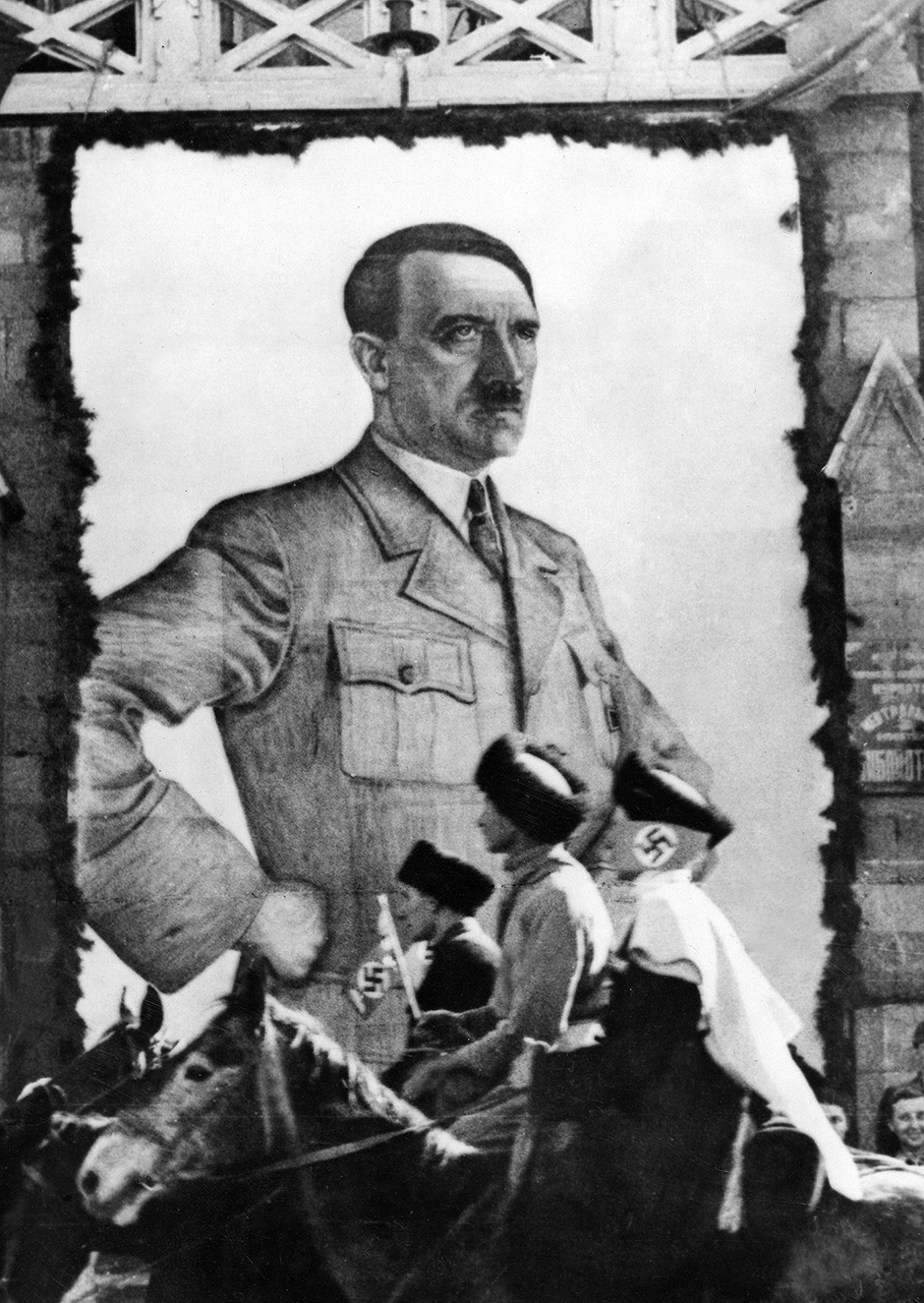

German strategy for Muslim mobilization remains of special interest in part because the rise of Nazism’s ideology of Jewish extermination coincided with Arab nationalist mobilization of anti-Semitism in Palestine. Infamously, Amin al-Husayni, an Arab nationalist whom the British had appointed as the grand mufti of Jerusalem, and whom Motadel describes as “peacock-like” and “an ardent Jew-hater,” accepted refuge in Berlin in late 1941. He met with Hitler and collaborated with Nazi propagandists during the remainder of the war. Nazi messages emphasized that Germany would liberate Muslims from British colonialism and Bolshevik atheism by rooting out the supposed controlling influence of Jews.

These claims certainly found receptive audiences in Palestine and in the wider Arab world. But the extent of Nazi influence on Arab attitudes toward Zionism is impossible to measure, not least because Nazi power in the Arab world proved to be short-lived. “Overall,” Motadel judges, “German propaganda failed.” Muslims ultimately fought in large numbers for Britain in North Africa and across the Middle East.

There were a few places where Muslims in territories occupied by Germany had to consider how to act amid the gathering Holocaust. In Nazi-occupied areas of the Balkans, some individual Muslims participated in the violence. Some stole copper from the rooftops of abandoned synagogues. Others courageously sought to protect potential pogrom targets. Overall, the role of Muslims in the killing of Jews and Roma, Motadel writes, “cannot be generalized, ranging, as elsewhere, from collaboration and profiteering to empathy and, in some cases, solidarity with the victims.”

Advertisement

Motadel’s history is one of two new volumes of scholarship that refresh our understanding of Nazi Germany’s involvement with the Middle East and the wider Muslim world. The second, Atatürk in the Nazi Imagination, by Stefan Ihrig, a fellow at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, is a thorough and inspired account of how the formation of modern Turkey influenced Hitler and other Nazi ideologists by providing a model of armed resistance to the Versailles Treaty, as well as an imagined example of muscular nationalism for a new century.

Neither Motadel nor Ihrig claims to provide connections to current politics or conflict in the Middle East. That is appropriate, given the character of their scholarship. And yet, during the latest American-led “great Jihad of Freedom” in Iraq and Syria, aimed at suppressing the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, both volumes have implications for understanding current history. Motadel in particular offers a portrait of continuity in the West’s strategies for mobilizing Islam in wartime or for using Islam for its geopolitical ends—a history, on the whole, of continual failure.

The aim of Atatürk in the Nazi Imagination is to document that the founder of modern Turkey deserves to be remembered as a figure equal to Mussolini in Hitler’s early political imagination. Mustafa Kemal Pasha, later glorified as Atatürk, had a record of military action that included cleansing what Hitler believed to be the inherently sapping multiethnicity of the expired Ottoman Empire.

Indeed, in Ihrig’s account, apart from Atatürk’s personal inspiration, the organized mass killing of Armenians by Turks during World War I—the events now recognized as the Armenian Genocide—explicitly influenced Hitler’s thinking about the extermination of Jews as early as the 1920s. Ihrig quotes a multipart essay published in Heimatland, an influential Nazi periodical, by Hans Tröbst, who had fought with the Kemalists during what Turks knew as the War of Independence:

The bloodsuckers and parasites on the Turkish national body were Greeks and Armenians. They had to be eradicated and rendered harmless; otherwise the whole struggle for freedom would have been put in jeopardy. Gentle measures—that history has always shown—will not do in such cases…. Almost all of those of foreign background in the area of combat had to die; their number is not put too low with 500,000. [emphasis in original]

In incipient Nazi historiography, Ihrig writes, “the ‘fact’ that the New Turkey was a real and pure völkisch state, because no more Greeks or Armenians were left in Anatolia, was stressed time and again, in hundreds of articles, texts, and speeches.” Of course, the Nazi Holocaust was constructed in its own setting, from its own sources; one should not overemphasize the Armenian precedent, and Ihrig does not. Yet here is a documented example from the early industrialization of ethnic murder in which one campaign of genocide influenced another.

Politically, Atatürk’s success offered a model of how to overcome the humiliation and prostration imposed on World War I’s losers at Versailles. Atatürk not only seized power through bold action in the name of the Turkish nation, he also forced European capitals to renegotiate the terms of the treaty they had imposed. This example, at least as much as Benito Mussolini’s March on Rome in late 1922, inspired Hitler’s failed Munich putsch of 1923. Afterward, in testimony at his trial, Hitler spoke of how Atatürk’s cleansing nationalism had carried the Turkish leader to power righteously: “Not from the rotten center, from Constantinople, could salvation come,” Hitler said. “The city was, just as in our case, contaminated by democratic-pacifistic, internationalized people, who were no longer able to do what is necessary. It could only come from the farmer’s country.”

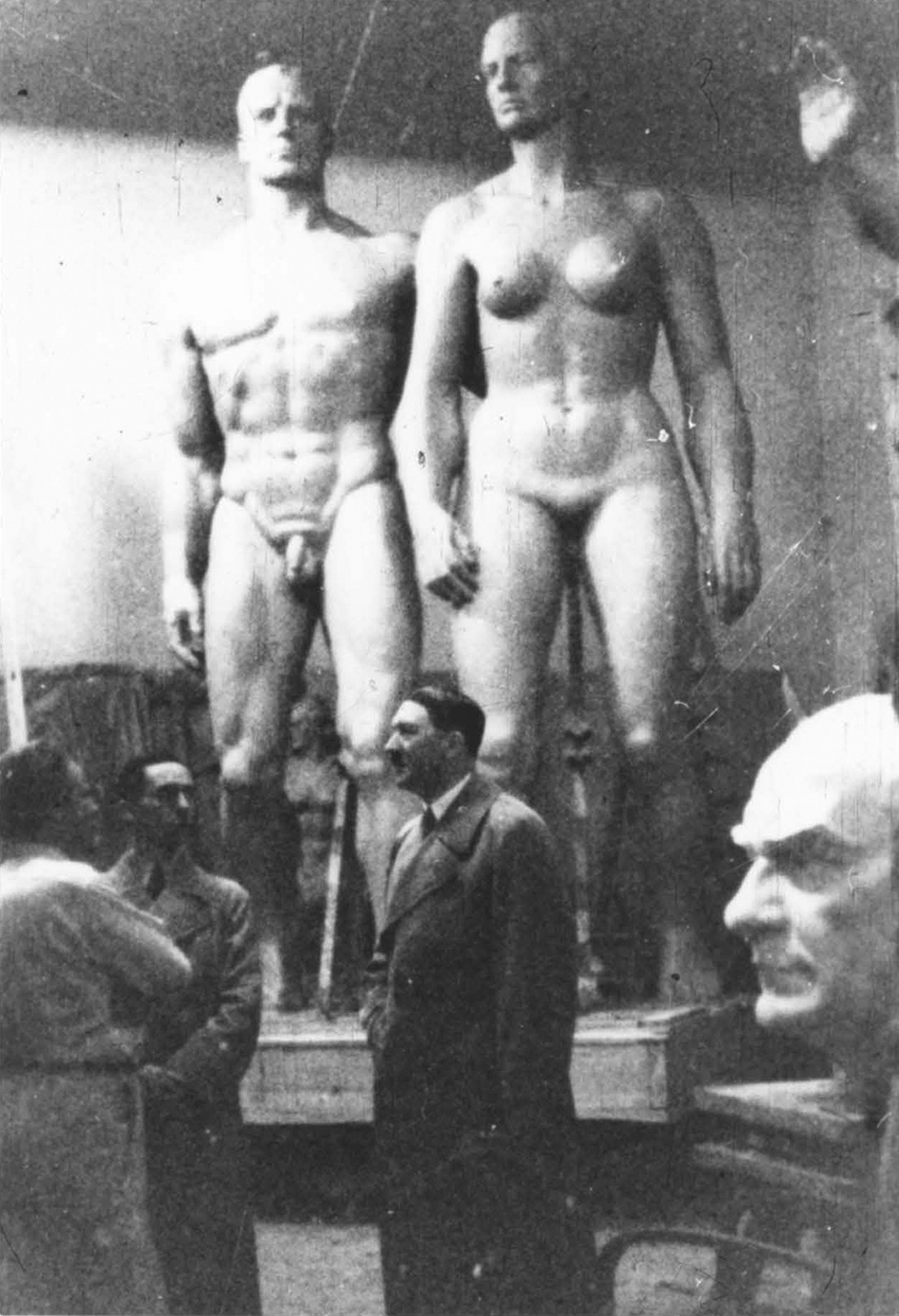

Ihrig’s book is illustrated with haunting political cartoons about Turkey’s example excavated from Nazi and other Weimar newspapers. The images make the point Ihrig intends, namely, that there can be no doubt about the significance of Atatürk’s inspiration in Nazi circles. They also remind us, as archival texts alone could not, how dark and threatening the German political imagination became after Versailles. Atatürk died in 1938, but Hitler’s admiration of him persisted until the Führer’s final days; he cherished a bust of Atatürk fashioned by the Nazi sculptor Josef Thorak.

Ihrig’s research supports Motadel’s conclusion that Nazi alliances with Islam should be understood as primarily instrumental, not ideological. Atatürk was an ardent secularist. Nazi writing that praised his purging of Ottoman weakness described the Islamic faith as “the great retarder, which prevented all progress.” This line of propaganda competed with another, however: that Muslims were Nazi Germany’s natural allies against Jews, Britain, and the Soviet Union. The contradiction is explained by two factors, as Motadel’s volume makes clear. One is that Hitler was a deeply confused thinker. The second is that Germany’s use of Islam during the Nazi period owed less to Hitler’s strategizing than to the legacy of imperial Germany’s use of armed jihadists to undermine its European enemies.

Advertisement

At the outbreak of World War I, German intelligence studied how best to stir Islamic revolts against Britain from India to Egypt. At German urging, in Constantinople, the Ottoman sultan, Mehmed V, issued fatwas calling on all of the world’s Muslims to rise up against the Entente powers. The sultan assured those who might fall to British rifles that they would be glorious martyrs. In Berlin, the Intelligence Office for the Orient sought to foment jihad in as much enemy imperial territory as possible.

Max von Oppenheim, the office leader, outlined the campaign in a 136-page paper entitled “Memorandum on the Revolutionizing of the Islamic Territories of Our Enemies.” His staff included a “vast” number of “academic experts, diplomats, military officials, and Muslim collaborators,” Motadel writes. Their incitements “caused no end of trouble,” a French army report noted during the war, and yet, Motadel concludes, the entire German effort was founded on “a misconception.” It assumed that there was fertile ground for a pan-Islamic revolt when there was none, and it failed to disguise Germany’s self-interested manipulations. “The Muslim world was far too heterogeneous” to respond to a single blueprint for revolt, and in any event, “it was all too clear that Muslims were being employed for the strategic purposes of the Central Powers, not for a truly religious cause.”

None of this stopped von Oppenheim and other Foreign Office officials who oversaw the campaign from advocating for its revival as Hitler launched another great war. In Hitler and Himmler, particularly, the advocates found receptive listeners. The record of Hitler’s private reflections on Islam is thin, drawn principally from the postwar memories of former intimates and colleagues. Yet he does seem to have been fascinated by Muslim faith and history. He reportedly described Islam as a more muscular belief system than Christianity and thus better suited for the Germany he wished to build.

According to Albert Speer, Hitler once offered a remarkable counterfactual history of Europe. He speculated about what might have been if the Muslim forces that invaded France during the eighth century had prevailed against their Frankish enemies at the Battle of Tours. “Hitler said that the conquering Arabs, because of their racial inferiority, would in the long run have been unable to contend with the harsher climate” of Northern Europe. Therefore, “ultimately not Arabs but Islamized Germans could have stood at the head of this Mohammedan Empire.”

Speer quoted Hitler expressing his enthusiasm about such an alternative inheritance: “You see, it’s been our misfortune to have the wrong religion…. The Mohammedan religion…would have been much more compatible with us than Christianity. Why did it have to be Christianity with its meekness and flabbiness?”

There are other accounts of Hitler expressing similar views. Eva Braun’s sister, Ilse, recorded that during his table talks, Hitler often discussed Islam and “repeatedly compared Islam with Christianity in order to devalue the latter, especially Catholicism,” in Motadel’s summary. “In contrast to Islam, which he portrayed as a strong and practical faith, he described Christianity as a soft, artificial, weak religion of suffering.”

Himmler’s fascination with Islam is more fully documented. His opinions ran along similar lines. Felix Kersten, Himmler’s doctor, wrote an entire chapter of his memoirs about his patient’s enthrallment with Islam and with the Prophet Muhammad. According to Kersten, Rudolf Hess introduced Himmler to the Koran, which Himmler sometimes kept at his bedside. He reportedly regarded the Prophet as one of history’s greatest men.

Himmler left the Catholic Church in 1936, and as the war later raged he sometimes reflected on Islam’s supposed advantages in motivating soldiers. “Mohammed knew that most people are terribly cowardly and stupid,” he told Kersten in 1942.

That is why he promised every warrior who fights courageously and falls in battle two [sic] beautiful women…. You may call this primitive and laugh about it…but it is based on deeper wisdom. A religion must speak a man’s language.

These reflections have a crackpot quality, as did much of the rest of Himmler’s thinking about the spiritual world, which included an interest in mysticism and the occult. It is, of course, no reflection on the Islamic faith that Himmler read its sacred text so shallowly or that he subscribed to the hoary cliché about Islam’s supposed martial character.

In recent years, writers such as the late Christopher Hitchens, a self-professed atheist, have introduced the neologism “Islamofascism” into popular use, while arguing that there are parallels between certain radical Muslim ideas about political economy and those of fascism. Outside of a few Fox News demagogues, the idea never took hold even on the right because it is so obviously oversimplified and ahistorical. It is true that Himmler distributed SS talking points arguing that “Islam and National Socialism have common enemies and also overlap in belief.” Yet this sort of propaganda arose mainly from cynicism.

Himmler’s public remarks about Islam made plain that his purpose was manipulative—part of a desperate effort, particularly toward the end of the war, to enlist Muslim troops to help forestall the Red Army’s counteroffensive. Himmler recruited, trained, and deployed exclusively Muslim SS divisions initially to bolster the Nazi occupation of the Balkans and the Caucasus, and then, after 1944, to try to reverse the losing course of the war. He once remarked:

I must say, I don’t have anything against Islam because it educates men…for me and promises them paradise when they have fought and been killed in battle. A practical and attractive religion for soldiers!

The essential instrumentality of Nazi attitudes toward Islam can be seen as well in the bizarre lengths to which Nazi propagandists went to amend Nazi racial policies in order to avoid offending potential wartime allies among Turks, Arabs, and Iranians. Privately, Hitler viewed these peoples as racially inferior. Publicly, he interpreted Nazism’s race theories to rationalize his military alliances.

“While the exclusion from racial discrimination could be backed by some race theory with regard to Persians and Turks,” Motadel writes, “the case of the Arabs was more problematic, as they were seen by most racial ideologues as ‘Semites.’” Yet Nazi officials were well aware early on that if they expected to challenge France and Britain militarily, they had to avoid offense to such Semites. “As early as 1935, the Propaganda Ministry therefore instructed the press to avoid the terms ‘anti-Semitic’ and ‘anti-Semitism’ and to use words like ‘anti-Jewish’ instead.” When German forces rolled into Bosnia in 1943, the SS ruled that the region’s Muslims were “racially valuable peoples of Europe.” They became the first Muslims inducted into the Waffen-SS.

During Germany’s invasion of the Caucasus and Crimea, the Wehrmacht’s initial efforts to revive Islamic culture, in order to undermine the Soviet Union, did have some success. Bolshevism’s repression of Islamic rituals and institutions was less than a generation old. When they arrived in the North Caucasus, Wehrmacht officers carefully staged the reopening of mosques and religious foundations and the reestablishment of religious holidays and celebrations. They allowed displays of Arabic and Koranic script in public, both of which the Soviets had banned. Some Muslim and community leaders in the East embraced German occupation as a way to restore their culture. Up to 20,000 Crimean Tatars fought Soviet forces in purely Muslim formations incorporated into the German 11th Army.

These soldiers and many other Muslims who cooperated with Germany paid a terrible price after its defeat. Stalin deported the Muslim populations of the Caucasus and Crimea to Central Asia and elsewhere. By agreeing to repatriate former Soviet citizens at Yalta, Britain and the United States became complicit in this horror. British and American soldiers detained former Muslim SS soldiers in special camps and turned the veterans and various Caucasian civilian refugees over to the Red Army in the summer of 1945. As Motadel recounts, some of these extraditions produced “dramatic scenes.”

Dozens jumped from moving trains. As they docked in Odessa, many others leaped from the deportation ships into the Black Sea; some committed suicide. One of the imams died in an act of self-immolation. In the Soviet Union many were massacred by Soviet cadres or deported to gulags…. Protests by the Red Cross made no impression on British and US authorities. The international press also showed little interest.

Such was the coda to Nazi Germany’s wartime engagement with Islam: a strategy born in cynicism, and fostered with the promotion of anti-Semitism, ended in mass civilian death and suffering among Muslims.

Nazi strategy left another legacy: it suggested a model for the United States during the cold war. In partnership with Saudi Arabia after the war, American strategists considered how a mobilized Islam might counter Soviet expansion in the Middle East. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, President Jimmy Carter authorized the CIA to provide covert aid to Afghan rebels—a revival, in effect, of the OSS’s “Jihad of Freedom.”

William Casey, President Reagan’s first CIA director, embraced the covert action program and took it further. He authorized printing Korans in the Uzbek language, so they could be smuggled by rebels across the Afghan border and distributed to Soviet citizens. Casey also authorized or at least turned a blind eye to guerrilla raids on Soviet territory carried out by rebels loyal to the Afghan Islamist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. (Hekmatyar, who received arms from the CIA, is still fighting in Afghanistan against the Afghan government and the United States.)

The anti-Soviet rebellion offers one of the few cases in history where the external rousing of Muslim fighters against a non-Muslim occupying power succeeded, at least militarily. Of course, that was primarily because the Afghan resistance was indigenous and well underway before the United States and Saudi Arabia arrived to stoke it with dollars and sophisticated arms. The outcomes of American intervention in Afghanistan against the Soviets included a devastating civil war and the birth of al-Qaeda. The policy therefore can hardly be judged a strategic triumph.

Still, as in Berlin between the wars, failure has proven no deterrent to persistence in Washington, where Pentagon planners continue to act as if they can win wars in the Middle East by deftly manipulating and arming tribes, sects, and Islamic leaders in scattered territories they barely know.

Motadel’s sophisticated narrative suggests at least two reasons why such Western strategies typically fail. One is the planners’ ignorance of Islam’s diversity and of the subtle part that faith plays in the daily lives of so many self-identified Muslims. That is, Westerners often overestimate Islam’s coherence and thus its pliability.

The second reason is written across the vast history of colonial and postcolonial European and American interventions in Muslim territories, from the two world wars to the three Gulf wars and now to the campaign against the Islamic State. Muslim populations called to arms by Washington, London, or Berlin on the grounds of common enemies and common interests have heard it all before. They have seen countless promises betrayed and one traumatic outcome of Western intervention after another. It is little wonder that so many find the summons to alliance unconvincing.