We do not think of Tolstoy as a comic writer, but his genius permits him to write farce when it suits him. There is a wickedly funny scene in Anna Karenina that directly precedes the painful scenes leading to Anna’s suicide. It takes place in the drawing room of the Countess Lydia Ivanovna, who, almost alone among the novel’s characters, has no good, or even pretty good, qualities. She embodies the kind of hysterical and coldhearted religious piety that Tolstoy was especially allergic to. “As a very young and rhapsodical girl,” he writes, she

had been married to a wealthy man of high rank, a very good-natured, jovial, and extremely dissipated rake. Two months after marriage her husband abandoned her, and her impassioned protestations of affection he met with a sarcasm and even hostility that people knowing the count’s good heart, and seeing no defects in the ecstatic Lydia, were at a loss to explain. Though they were not divorced, they lived apart, and whenever the husband met the wife, he invariably behaved to her with the same venomous irony, the cause of which was incomprehensible.

Tolstoy, with his own venomous irony, makes the cause entirely comprehensible to the reader of Anna Karenina, as he shows Lydia Ivanovna fasten herself on Karenin after Anna leaves his house to go abroad with Vronsky, and preside over his degeneration into his worst self. She is an ugly and malevolent creature who coats her spite in a thick ooze of platitudes about Christian love and forgiveness. When Anna was on the verge of death after giving birth to Vronsky’s daughter, Karenin experienced an electrifying spiritual transformation: his feelings of hatred and vengefulness toward Anna and Vronsky abruptly changed into feelings of love and forgiveness, and under the spell of this new “blissful spiritual condition” he offered Anna a divorce and the custody of her son—neither of which she chose to accept. Now, a year later, she wants the divorce, but Karenin is no longer of a mind to give it to her. The blissful spiritual condition has faded away like a rainbow, and Karenin, in thrall to the malignant Lydia Ivanovna, has reassumed his old, supinely rigid, and unfeeling self.

Anna’s brother, Stepan Arkadyevich (Stiva) Oblonsky, has gone to Karenin to intercede for Anna, and Karenin has said he would think the matter over and give his answer in two days’ time, but when the two days pass, instead of an answer, Oblonsky receives an evening invitation to the house of Lydia Ivanovna, where he finds her and Karenin and a French clairvoyant named Landau, who is to be somehow instrumental in Karenin’s decision. The comic scene that follows is filtered through Oblonsky’s consciousness.

By now we know Oblonsky very well. Tolstoy has portrayed him as a person whom it is necessary to condemn—he is another dissipated rake—but impossible to dislike. He radiates affability; when he comes into a room people immediately cheer up. And when he appears on the page, the reader feels a similar delight. In the novel’s moral hierarchy, Lydia Ivanovna and Karenin occupy the lowest rung; they sin against the human spirit, while Stiva only sins against his wife and children and creditors. Through his geniality, Oblonsky has been able to maintain a job in government for which he is in no way qualified, but now, because he needs more money, he is trying to get himself appointed to a higher-paying position in the civil service. Lydia Ivanovna has influence among the appointers, and Oblonsky figures he might as well use the occasion to charm her into helping him. Thus, while listening to Lydia Ivanovna and Karenin’s odious religious palaver, he cravenly—but, he hopes, not too cravenly—hides his atheism:

“Ah, if you knew the happiness we know, feeling His presence ever in our hearts!” said Countess Lydia Ivanovna with a rapturous smile.

“But a man may feel himself unworthy sometimes to rise to that height,” said Stepan Arkadyevich, conscious of hypocrisy in admitting this religious height, but at the same time unable to bring himself to acknowledge his freethinking views before a person who, by a single word to Pomorsky, might procure him the coveted appointment.

During all this Landau, “a short, thinnish man, very pale and handsome, with feminine hips, knock-kneed, with fine brilliant eyes and long hair” and a “moist, lifeless” handshake, is sitting apart at a window. Karenin and Lydia Ivanovna look at each other and make cryptic remarks about him. A footman keeps coming into the room with letters for Lydia Ivanovna, to which she rapidly scribbles answers or gives brief spoken answers (“Tomorrow at the Grand Duchess’s, say”), before resuming her pieties, to which Karenin adds pieties of his own. Stiva feels increasingly baffled. Lydia Ivanovna suddenly asks him, “Vous comprenez l’anglais?” and when he says yes, she goes to her bookcase and takes down a tract called Safe and Happy, from which she proposes to read aloud. Stiva feels safe and happy at the chance to collect himself and not have to worry about putting a foot wrong. Lydia Ivanovna prefaces her reading with a story about a woman named Marie Sanina who lost her only child, but found God, and now thanks Him for the death of her child—“such is the happiness faith brings!” As he listens to Lydia Ivanovna read Safe and Happy,

Advertisement

aware of the beautiful, artless—or perhaps artful, he could not decide which—eyes of Landau fixed upon him, Stepan Arkadyevich [begins] to be conscious of a peculiar heaviness in his head.

The most incongruous ideas were running through his mind. “Marie Sanina is glad her child’s dead…How good a smoke would be now!… To be saved, one need only believe, and the monks don’t know how the thing’s to be done, but Countess Lydia Ivanovna does know…And why is my head so heavy? Is it the cognac, or all this being so strange? Anyway, I think I’ve done nothing objectionable so far. But, even so, it won’t do to ask her now. They say they make one say one’s prayers. I only hope they won’t make me! That’ll be too absurd. And what nonsense she’s reading! But she has a good accent….”

Stiva fights the drowsiness that is overcoming him, but begins to helplessly succumb to it. On the point of snoring, he rouses himself, but too late. “He’s asleep,” he hears the countess saying. He has been caught out. The countess will never help him with the appointment. But no, the countess isn’t talking about him. She is talking about the clairvoyant. He is lying back in his chair with his eyes closed and his hand twitching. He is in the trance Lydia Ivanovna and Karenin have been waiting for him to fall into. She instructs Karenin to give Landau his hand and he obeys, trying to move carefully, but stumbling on a table. Stiva watches the scene, not sure he isn’t dreaming it. “It was all real,” he concludes.

With his eyes closed, the clairvoyant speaks: “Que la personne qui est arrivée la dernière, celle qui demande, qu’elle sorte! Qu’elle sorte!” Let the person who was the last to come in, the one who asks questions, let him get out! Let him get out! Stiva, “forgetting the favor he had meant to ask of Lydia Ivanovna, and forgetting his sister’s affairs, caring for nothing, but filled with the sole desire to get away as soon as possible, [goes]out on tiptoe and [runs] out into the street as though from a plague-stricken house.” It takes him a long time to regain his equanimity. The next day he receives from Karenin a final refusal of the divorce and understands “that this decision was based on what the Frenchman had said in his real or pretended trance the evening before.”

It was all real. There has been a great deal written about the preternatural realism of Anna Karenina, and about the novel’s special status as a kind of criticism-proof text because of the reader’s feeling that what he is reading is being effortlessly reported rather than laboriously made up. “We are not to take Anna Karénine as a work of art; we are to take it as a piece of life,” Matthew Arnold wrote in 1887. “The author has not invented and combined it, he has seen it; it has all happened before his inward eye, and it was in this wise that it happened.” In 1946 Philip Rahv elaborated on Arnold’s idea:

In the bracing Tolstoyan air, the critic, however addicted to analysis, cannot help doubting his own task, sensing that there is something presumptuous and even unnatural, which requires an almost artificial deliberateness of intention, in the attempt to dissect an art so wonderfully integrated…. Such is the astonishing immediacy with which he possesses his characters that he can dispense with manipulative techniques, as he dispenses with the belletristic devices of exaggeration, distortion, and dissimulation…. The conception of writing as of something calculated and constructed—…upon which literary culture has become more and more dependent—is entirely foreign to Tolstoy.

Tolstoy—one of literature’s greatest masters of manipulative techniques—would smile at this. The book’s “astonishing immediacy” is nothing if not an object of the exaggeration, distortion, and dissimulation through which each scene is rendered. Rahv calls these devices belletristic but long before anyone wrote belles lettres everyone who dreamed was practiced in their use. If the dream is father to imaginative literature, Tolstoy may be the novelist who most closely hews to its deep structures. As we read Anna Karenina we are under the same illusion of authorlessness we are under as we follow the stories that come to us at night and seem to derive from some ancient hidden reality rather than from our own, so to speak, pens. Tolstoy’s understanding of the sly techniques of dream-creation is at the heart of his novelist’s enterprise. Like the films shown in the movie houses of our sleeping minds, Tolstoy’s waking scenes draw on a vast repertory of collective emotional memory for their urgency.

Advertisement

Take the famous ballroom scene at the beginning of the novel in which Anna and Vronsky fall in love as if forced to do so by a love potion in a room filled with tulle and lace and music and scent. The scene has inscribed itself on our memories as one of the most vividly romantic scenes in literature. Who can forget the sight of Anna in her simple black gown that shows off her beauty rather than its own and sets her apart from all the other women in the room? As Tolstoy describes her—practically caressing her as he does so—we fall in love with her ourselves. How could Vronsky resist her?

But wait. It isn’t Tolstoy who describes Anna—it is through the eyes of Kitty Scherbetskaya that we see her. The scene is written not as a romance but as a nightmare. Kitty, who loves Vronsky, has come to the ball in the happy expectation that he will propose to her. As in our worst nightmares, when a horrified realization of disaster comes upon us and will not let go of us, Kitty’s delight turns to horror as she watches Anna and Vronsky displaying the signs of people falling in love, and grasps the full extent of Vronsky’s indifference to her. Kitty will hate Anna for the rest of her life, but Tolstoy—to render his effect of Anna’s powerful sexual magnetism—captures the moment when Kitty is herself attracted to Anna. Tolstoy places or rather displaces the weight of Kitty’s crushing mortification onto the mazurka that she assumed she would dance with Vronsky and for which she now finds herself without a partner. In writing the scene as an archetypal nightmare of jealousy—in refracting Anna and Vronsky’s passion through the prism of Kitty’s anguish—Tolstoy performs one of the hidden tours de force by which his novel is animated.

The horse race offers another example of Tolstoy’s use of the archetypal nightmare as a literary structure. This time his model is the dream of lateness. In this dream, no matter what we do, no matter how desperately we struggle, we cannot get to the airport, or the play, or the final examination in time. Something holds us back and we struggle against it to no purpose. On the morning of the race Vronsky makes a visit to the mare he is going to ride (and kill). The English trainer asks him where he is planning to go after he leaves the stable, and when Vronsky tells him he is going see a man named Bryansky, the Englishman—evidently not believing him, knowing, as others seem to know, that he is going to visit Anna—says, “The vital thing’s to keep quiet before a race…don’t get disturbed or upset about anything.”

Vronsky drives out to Anna’s summer house and becomes predictably disturbed and upset when she tells him she is pregnant. He leaves for Bryansky’s house to give him some money—he wasn’t lying to the trainer, just not telling the whole truth—and the nightmare proper of lateness begins. Only on the way to Bryansky does he look at his watch and see that it is much later than he thought and that he never should have started out. Should he turn back? No, he decides to keep going. He believes he will just make the race.

At this point, Tolstoy veers away from the classic dream of lateness in which the dreamer never arrives at his destination and allows Vronsky to make the race. But Vronsky is clearly not in the right state of mind. An unpleasant encounter with his brother, who wants him to end the affair with Anna, is another assault on the necessary condition of quiet. When disaster strikes, when Vronky makes the wrong move that breaks the mare’s back, it registers, as these things do when we dream them, as a terrifying inevitability.

All dreams are not nightmares, of course. As we sometimes awaken from a dream in tears, so a number of Tolstoy’s scenes draw on the sentimentality—a sort of basic bathos—that is lodged in the hearts of all but the most high-minded among us. One such scene takes place the day after the ball, when her sister Dolly comes to the humiliated Kitty’s room in her parents’ house and finds her sitting and staring at a piece of rug. Kitty rejects Dolly’s attempts to make her feel better, is cold and unpleasant to her, and finally silences her by spitefully flinging Stiva’s philandering in her face. “I have some pride, and never, never would I do as you’re doing—go back to a man who’s deceived you, who has cared for another woman. I can’t understand it. You may, but I can’t!” Tolstoy continues:

And saying these words, she glanced at her sister, and seeing that Dolly sat silent, her head mournfully bowed, Kitty, instead of running out of the room, as she had meant to do, sat down near the door and hid her face in her handkerchief.

The silence lasted for a minute or two. Dolly was thinking of herself. That humiliation of which she was always conscious came back to her with a peculiar bitterness when her sister reminded her of it. She had not expected such cruelty from her sister, and she was angry with her. But suddenly she heard the rustle of a skirt, and with it the sound of heart-rending, smothered sobbing, and felt arms about her neck. Kitty was on her knees before her.

“Dolinka, I am so, so wretched!” she whispered penitently. And the sweet face covered with tears hid itself in Darya Aleksandrovna’s skirt.

The novel is filled with such passages (another is the scene in which Dolly comes upon her daughter Tanya and her son Grisha eating cake and crying over Tanya’s kindheartedness in secretly sharing it with him after he had been forbidden dessert as a punishment) that do not advance its plot—almost seem to retard its forward motion—but heighten the sense of piercing reality Arnold and Rahv could find no words to account for.

The novel is also filled with accounts of actual dreams experienced by characters that entirely lack the vividness of the scenes of waking life. They seem, in their various ways, flat, formulaic, even boring. When Anna dreams of sleeping with both Karenin and Vronsky, we get the point—and feel that Tolstoy is not being very subtle. On the morning after Dolly confronts Stiva with the evidence of his affair with a former governess, he awakens in the study to which he has been banished from this uninterestingly incomprehensible dream:

Alabin was giving a dinner at Darmstadt; no, not Darmstadt, but something American. Yes, but then, Darmstadt was in America. Yes, Alabin was giving a dinner on glass tables, and the tables sang Il mio tesoro—not Il mio tesoro, though, but something better, and there were some sort of little decanters on the table, and they were women, too.

“Yes, it was nice, very nice.” Stiva recalls. “There was a great deal more that was delightful, only there’s no putting it into words, or even expressing it in one’s thoughts once awake.” Tolstoy was obviously well acquainted with the guard who stops us at the border of sleep and awakening and confiscates the brilliant, dangerous spoils of our nighttime creations. The capacity to recreate these fictions in the unprotected light of day may be what we mean by literary genius. As the full realization of the mess he has made of his domestic life comes over Stiva, he reflects that “to forget himself in sleep was impossible now, at least till nighttime; he could not go back now to the music sung by the decanter women; so he must forget himself in the dream of daily life.”

In January 1878, a professor of botany named S.A. Rachinsky wrote to Tolstoy about what he felt to be “a basic deficiency in the construction” of Anna Karenina, namely that “the book lacks architectonics.” To which Tolstoy replied,

Your opinion about Anna Karenina seems wrong to me. On the contrary, I take pride in the architectonics. The vaults are thrown up in such a way that one cannot notice where the link is. That is what I tried to do more than anything else. The unity in the structure is created not by action and not by relationships between the characters, but by an inner continuity.

One of these continuities—perhaps the most significant—is Tolstoy’s keen, almost prying, interest in the sexuality of his characters and the hierarchy he has set in place that runs parallel to, though distinct from, his moral hierarchy. At the top he has set his sexually robust characters—Anna, Vronsky, Oblonsky, Levin, Kitty, and Dolly—and to the bottom he has consigned figures like the creepy Landau and Varenka, a sexless young woman Kitty meets at the spa to which she has been sent to cure her broken heart, and whose limp handshake is echoed a hundred pages later by Landau’s flaccid grip. Levin’s bloodless-intellectual half-brother Sergey Ivanovich Koznishev, a kind of double of the bloodless-intellectual Karenin (as Lydia Ivanovna is a double of another dreadful pious woman named Madame Stahl—the novel is filled with doubles and doublenesses), is another member of the league of the sexually underpowered, though his portrait is a mere sketch in comparison to the full-blown case study of impotence that Tolstoy has fashioned out of his complicated cuckold.

He allows us to study Karenin both from the point of view of his sexually unfulfilled wife and, most interestingly, from his own sense of how he doesn’t measure up to other men. At a court event, the flatfooted and wide-hipped Karenin keeps looking at the attractive, powerfully built court functionaries around him and asks himself

whether they felt differently, did their loving and marrying differently, these Vronskys and Oblonskys…these fat-calved chamberlains…those juicy, vigorous, self-confident men who always and everywhere drew his inquisitive attention in spite of himself.

Anna is the special case of poetical sexual awakening turning into terrifying erotomania that reflects Tolstoy’s own famous craziness about sex, which in some sense is what the novel is “about.” The transformation of the wonderful Anna we first meet at the railway station—“the suppressed eagerness which played over her face…as though her nature was so brimming over with something that against her will it showed itself now in the flash of her eyes, and now in her smile”—into the psychotic who throws herself in front of a train is chronicled over the book’s length, and doesn’t add up.

Standard readings of the novel attribute Anna’s descent into madness to the loss of her son and to her ostracism by society. But in fact, as Tolstoy unambiguously tells us, the situation is of her own making. She did not lose her son—she abandoned him when she left for Italy with Vronsky after her recovery from the puerperal fever that propelled Karenin into his “blissful spirituality.” Under its influence, he was willing to give up his son and give Anna a divorce that would permit her to marry Vronsky and rejoin respectable society as, even in those days, divorced women were able to do. But as the novel goes on and Anna’s life unravels, it is as if this opportunity had never arisen. We experience the novel, as we experience our dreams, undisturbed by its illogic. We accept Anna’s disintegration without questioning it. Only later, when we analyze the work, does its illogic become apparent. But by then it is too late to reverse Tolstoy’s spell.

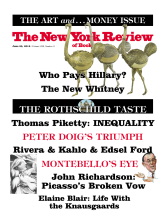

This Issue

June 25, 2015

In the New Whitney

Looking After the Knausgaards