This essay by Mark Strand was originally written for The New York Review of Books as a review of the exhibition of Edward Hopper’s drawings at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2013. It was found as a handwritten text in his notebook after he died in November 2014 and transcribed by his literary executor, Mary Jo Salter.

—The Editors

1.

Paints and scrapes, paints and scrapes to get something right, the something that is not there at the outset but reveals itself slowly, and then completely, having traveled an arduous route during which vision and image come together, for a while, until dissatisfaction sets in, and the painting and scraping begin again. But what is it that determines the success of the final work? The coincidence of vision—his idea, vague at first, of what the painting might be—and the brute fact of the subject, its plain obdurate existence, just “out there” with an absolutely insular existence.

Until, that is, Edward Hopper sees something about it as a possible subject for a painting and this image with its possibilities lodges itself in Hopper’s imagination and the formation of the painting’s content begins—content being, of course, what the artist brings to his subject, that quality that makes it unmistakably his, so when we look at the painting of a building or an office or a gas station, we say it’s a Hopper. We don’t say it’s a gas station. By the time the gas station appears on canvas in its final form it has ceased being just a gas station. It has become Hopperized. It possesses something it never had before Hopper saw it as a possible subject for his painting. And for the artist, the painting exists, in part, as a mode of encountering himself. Although the encountered self may not correspond to the vision of possibility that a particular subject seemed to offer up. When Hopper said, in an interview with Brian O’Doherty, “I’m after ME,” this is undoubtedly what he meant.

Hopper’s avowed uncertainty over whether or not he ever succeeded is perhaps what many painters experience. The point of arrival or the point when the painting is done cannot be known beforehand and yet cannot be totally unknown. A sense—it is no more than that, increasingly clearer and more convincing—of what the painting will look like when it is finished is all that guides the painter. And there is rarely any assurance that the painting is finally completed; the possibility always exists that a wrong turn has been taken, that what he ended up with bears little resemblance to that vague suggestion or hope of what the painting might be. And so, the scraping and painting begin yet again. With the uncertainty under which the painter labors, extended periods of doubt, it is a wonder that he can ever be free of anxiety or finish a work. Even the prodigiously talented Picasso needed constant reassurance.

One of the ways Hopper dealt with his lack of certainty was to make many preparatory drawings for each painting; this was especially true of his oils. The recent show at the Whitney Museum makes this abundantly clear.* It is probably the best and most informative show of Hopper’s work and certainly the best in recent memory. Hopper’s drawings have never been paid the kind of attention they deserve. In fact, if one were to look solely at the paintings, one might conclude, as some have, that Hopper was a mediocre draftsman.

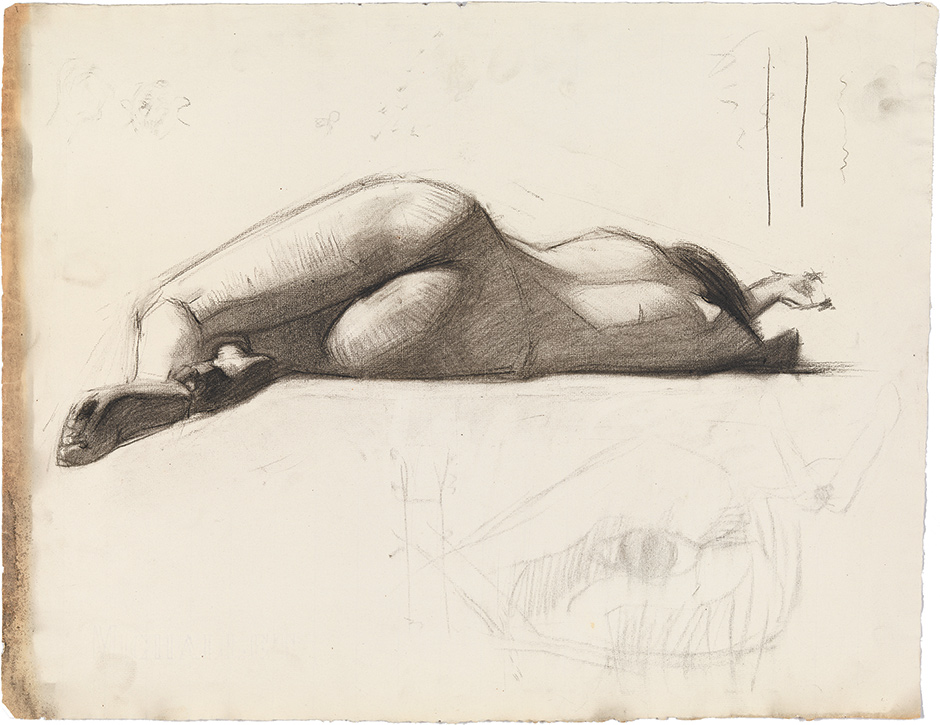

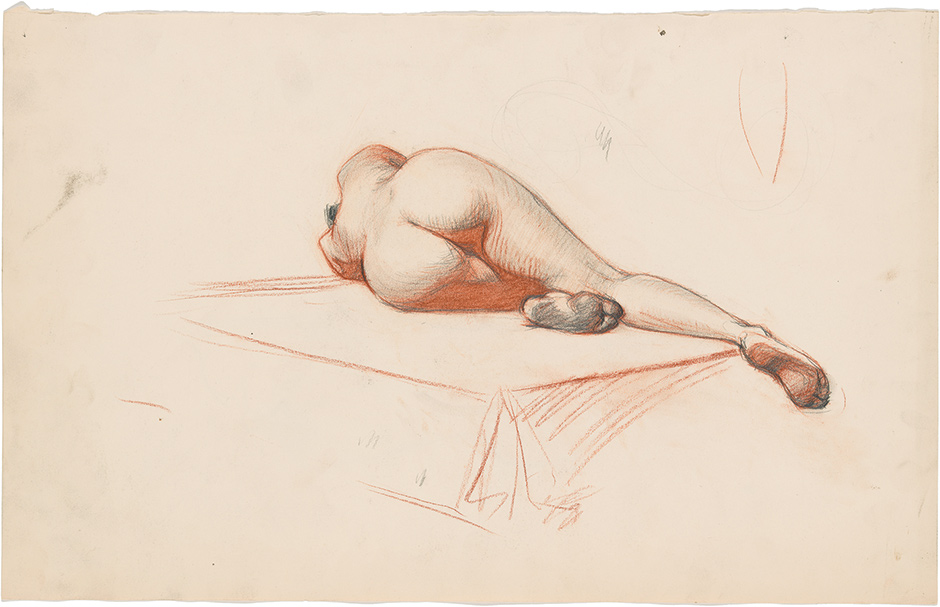

Hopper himself, though he saved his drawings, never considered them to be on a par with his paintings. But the early studies, always of the figure, would often be done for their own sake, and would not be part of the larger project of a painting. And these demonstrate his unusual gifts as a draftsman; the Whitney exhibition includes two spectacularly graceful and languorous reclining nudes that can be appreciated for their own sake and not for the ways they contribute to the makeup of a painting. Other early drawings have a strictly exploratory character: a look or a gesture, investigated for its own sake and not necessarily contributory to a painting.

His gift for drawing seemed to have been common knowledge at the New York School of Art, where his classmate Rockwell Kent thought that of all the students he was the best draftsman, and called him the John Singer Sargent of the class. Into the 1920s there are many impressive landscape drawings—one exceptional one of a tree trunk—and many nudes done at the life drawing classes held at the Whitney Studio Club from 1920 to 1925. But the drawings that are studies for particular paintings, done in series and in exhaustive detail, have a rough, sketchy identity and are obviously not intended to be viewed as anything but contributory to painting. The changes from sketch to sketch often seem so minor, each one no more than a dress rehearsal for the next, that one wonders how much, if any, information each contains or even if this was their purpose.

Advertisement

This is clearly the case in the many preparatory sketches for New York Movie (1939). It is possible that they serve another purpose, one much more fundamental to the elusive character possessed by all of Hopper’s paintings. They may have been a way of familiarizing himself with the subject of the painting, the ultimate aim of which was to own it imaginatively. The drawings thus form a ritual by which he can feel absolutely free and in control of the subject. It was not that he needed to be sure how to paint a sugar dispenser or salt shaker as in Nighthawks (1942), but that they should become his.

This absorption of the outer world into his inner world could only be accomplished through a protracted ritual of drawing and redrawing, slight adjustments here and there adding up to imaginative ownership and psychic freedom. Thus, later, during the process of painting he could make slight changes without recourse to drawings—the domain of the painting was already his. And yet, despite how familiar the picture may be, the painting and scraping continue, each slight adjustment an additional step toward the realization of a vision. What perhaps will always remain unknown is what led Hopper to select particular subjects for paintings.

Clearly, part of it had to do with the degree to which they suggested the possibility of becoming one of his paintings—that is, whether or not they already contained the physical properties he could manipulate or refine until they became unmistakably his. And how to characterize that world, instantly recognizable, but obdurately strange, a mixture of the ordinary and the uncanny? It is hard to put one’s finger on what makes them so, unless it is the imposition of the artist’s will, visible everywhere in general but nowhere in particular. It is this, perhaps more than anything else, that accounts for the continuing fascination he holds for viewers everywhere.

Recent major exhibitions in London, Paris, Rome, and Madrid testify to the universality of his appeal. It couldn’t be just the way New York looked in the first half of the twentieth century or the dated look of hotel rooms, of people in offices, staring blankly or dreamily into space, that accounts for such interest. Something lifts the paintings beyond the representational registers of realism into the suggestive, quasi-mystical realm of meditation. Moments of the real world, the one we all experience, seem mysteriously taken out of time. The way the world glimpsed in passing from a train, say, or a car, will reveal a piece of a narrative whose completion we may or may not attempt, but whose suggestiveness will move us, making us conscious of the fragmentary, even fugitive nature of our own lives. This may account for the emotional weight that so many Hopper paintings possess. And why we lapse lazily into triteness when trying to explain their particular power. Again and again, words like “loneliness” or “alienation” are used to describe the emotional character of his paintings.

2.

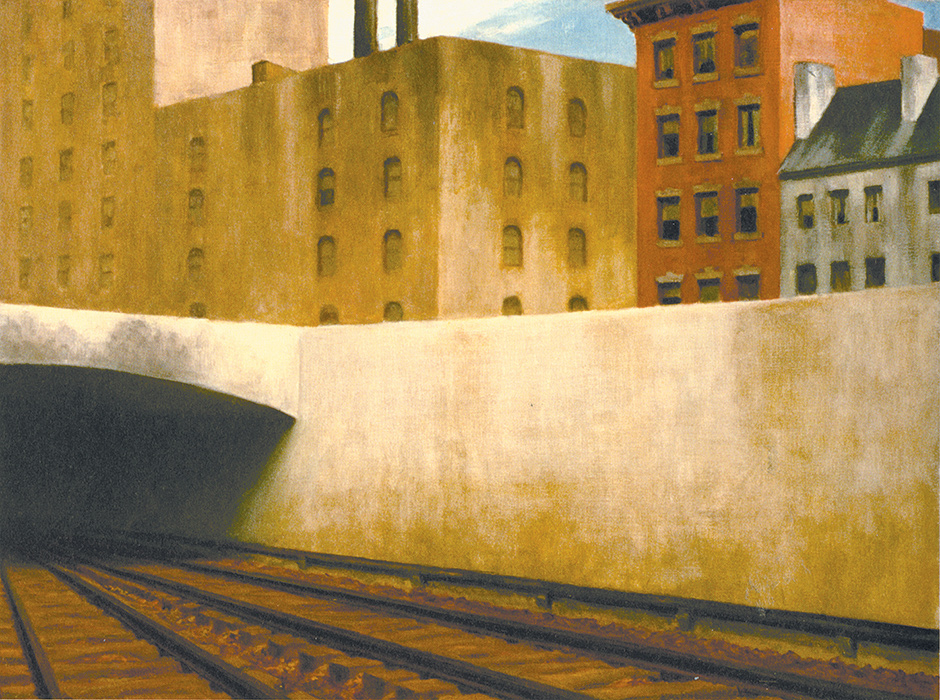

My own encounters with this elusive element in Hopper’s work began when I would commute from Croton-on-Hudson to New York each Saturday to take a children’s art class in one of those buildings on the south side of Washington Square that were eventually torn down to make room for NYU’s law school. This was in 1947. Just a year after Hopper painted Approaching a City (1946), I would look out from the train window onto the rows of tenements whose windows I could look into and try to imagine what living in one of those apartments would be like. And then at 99th Street we would enter the tunnel that would take us to Grand Central. It was thrilling to suddenly go underground, travel in the dark, and be delivered to the masses of people milling about in the cavernous terminal. Years later, when I saw Approaching a City for the first time, I instantly recalled those trips into Manhattan and have ever since. And Hopper, for me, has always been associated with New York, a New York glimpsed in passing, sweetened with nostalgia, a city lodged in memory.

Subsequently, my feelings about Hopper have grown more complicated. The paintings’ strangeness has increased, their curious unerotic character despite the prevalence of naked or near-naked women in bedrooms, their inwardness, their suggestion of melancholy without any obvious signs—except in some obvious examples—that melancholy is in fact being enacted. In the scrupulously attentive and informative catalog of the recent Hopper drawing show at the Whitney there is a short, brilliant essay by Mark W. Turner that compares the wall in Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener and Hopper’s walls. He quotes this telling passage:

Advertisement

I placed his desk close up to a small side-window in that part of the room, a window which originally had afforded a lateral view of certain grimy backyards and bricks, but which, owing to subsequent erections, commanded at present no view at all, though it gave some light. Within three feet of the panes was a wall, and the light came down from far above, between two lofty buildings, as from a very small opening in a dome. Still further to a satisfactory arrangement, I procured a high green folding screen, which might entirely isolate Bartleby from my sight, though not remove him from my voice. And thus, in a manner, privacy and society were conjoined.

This applies most directly to Office at Night (1940), but to a certain extent to other paintings as well.

The particular lack of eroticism in Hopper’s paintings of women alone in rooms may be explained, at least in part, by the fact that they belong so forcefully to the formal nature of the rooms. This accounts for a certain neutrality they have and tempers whatever emotional character they possess. And if Hopper’s statement is true—that as he painted he was pursuing himself, that he hoped to find himself in what he painted, meaning finally that the paintings reflected their maker, not simply his identity as a painter but something of himself as a human being—then Hopper himself must have been strangely reticent, emotionally hidden.

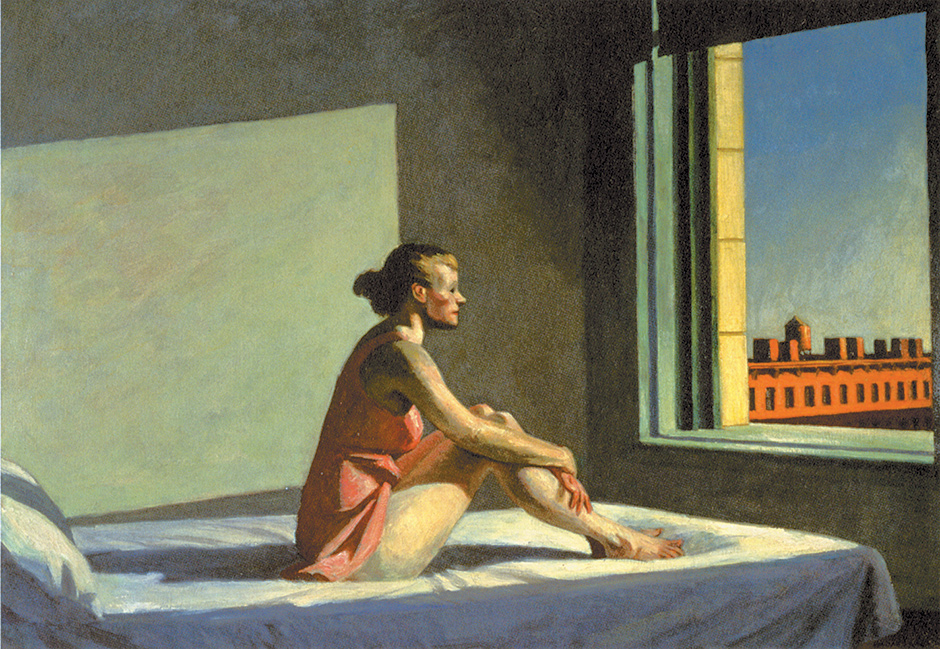

His women do not seem to have lives apart from the rooms in which we find them. They peer out into a world, the one the rest of us occupy—and it may be with a degree of longing—but it is not their world. And it is this detachment from our world that compromises their erotic presence. They are unavailable. We feel it as certainly as we do the assertive geometrical character of the rooms they occupy. This spatial solidity is what lends the paintings an air of permanence and fixes the woman in place, as in Morning Sun (1952).

So much so that imagining them in any other context represents only a form of escape on the viewer’s part from the imprisoning resolution of the painting. The tendency to create narratives around the works of Hopper only sentimentalizes and trivializes them. The women in Hopper’s rooms do not have a future or a past. They have come into existence with the rooms we see them in. And yet, on some level, these paintings do invite our narrative participation—as if to show how inadequate it is. No, the paintings are each a self-enclosed universe in which its mysteriousness remains intact, and for many of us this is intolerable. To have no future, no past would mean suspension, not resolution—the unpleasant erasure of narrative, or any formal structure that would help normalize the uncanny as an unexplainable element in our own lives.

-

*

“Hopper Drawing,” an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, May 23–October 6, 2013; the Dallas Museum of Art, November 17, 2013–February 16, 2014; and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, March 15–June 22, 2014. Catalog of the exhibition by Carter E. Foster and others (Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013). ↩