Academic philosophy often draws ire. The complaints are twofold and not altogether consistent with each other.

The first is that philosophers can’t seem to agree on anything, with dissension descending to such basic questions as the nature of the field itself, both its subject matter and its methodology. The lack of unanimity implies a lack of objectivity and suggests that any hope for progress is futile. This complaint often comes from scientists and culminates in the charge that there is no such thing as philosophical expertise. Who then are these people employed in philosophy departments, and what entitles them to express subjective viewpoints with the pretensions of impersonal knowledge?

The second complaint is that academic philosophy has become inaccessible. For more than a century now, the kind of philosophy practiced in most philosophy departments, at least in the English-speaking world, is analytic philosophy, and analytic philosophy, or so goes the lament, is too technical, generating vocabularies and theories aimed at questions remote from problems that outsiders consider philosophical. Here the complaint is that there are philosophical experts and that, in carrying the field forward, they have excluded the nonprofessional. The suppressed premise is that philosophical questions are of concern to all of humanity and therefore ought to remain within reach of all of humanity.

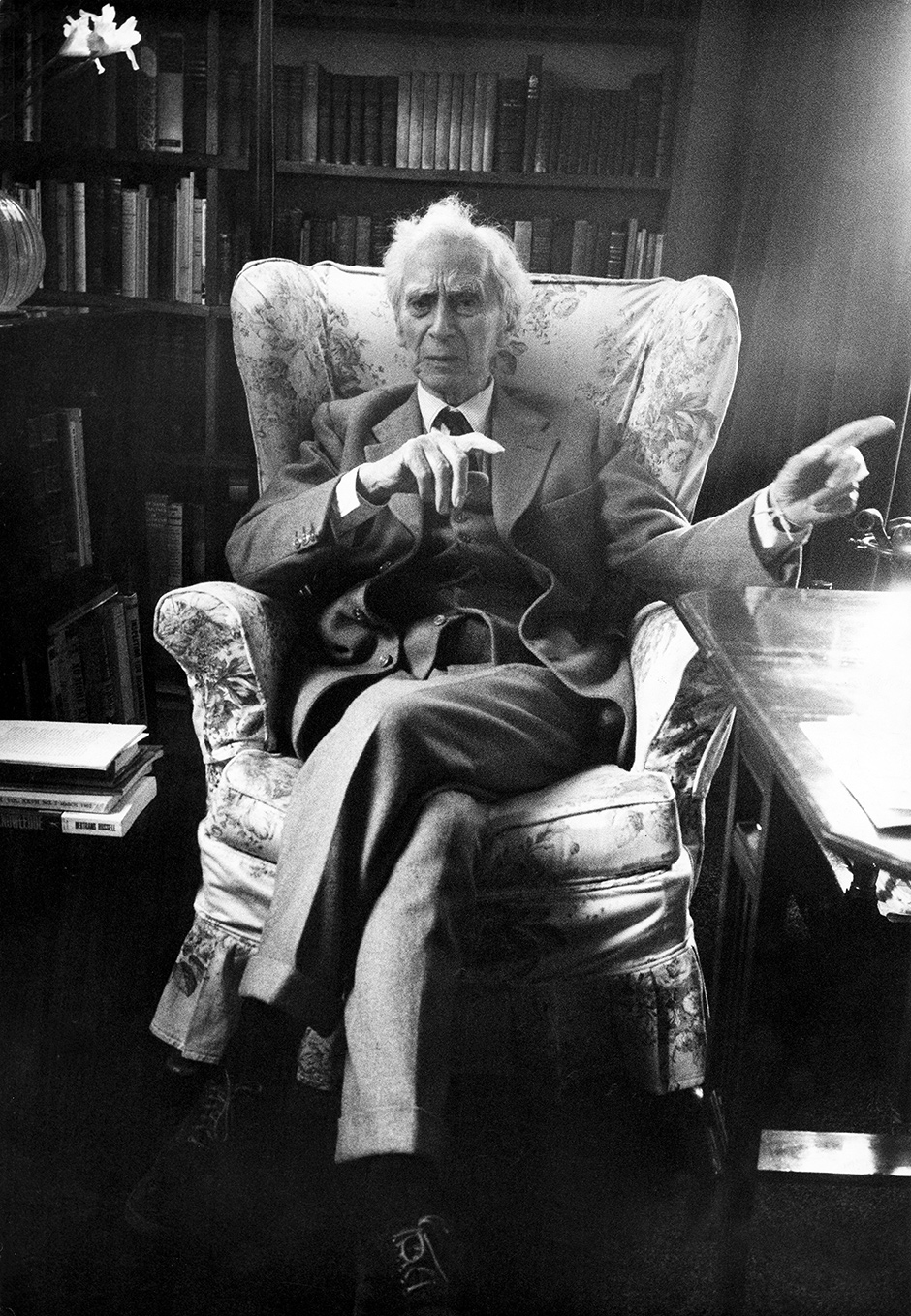

Analytic philosophy originated with philosophers who also did seminal work in mathematical logic, most notably Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell, and the alliances with both formal logic and science are among its defining features. As such, analytic philosophy values conceptual clarity and argumentative precision, its techniques are developed in their service, and it condemns the turgid language (and, perhaps not coincidentally, the indifference or hostility to science) characteristic of what many people think of as philosophy. Hegelian idealism was the prototype of what early analytic philosophers thought philosophy should not be, and today such thinkers as Martin Heidegger and Slavoj Žižek have stepped into that role.

Philosophy of language has been, from the beginning, close to the center of analytic philosophy, and Colin McGinn’s Philosophy of Language: The Classics Explained plunges one into philosophy as it is actually practiced by a majority of Anglo-American philosophers. Anyone who is put off by philosophy’s technical turn might be ill-disposed toward McGinn’s book. But I hope this pellucid exposition of some of analytic philosophy’s most technical achievements will persuade the persuadable that philosophers really have something to be expert about and that, with an able guide and a bit of intellectual effort, thoughtful people can profit from their work.

McGinn himself makes humbler claims for his book, the fruit of thirty-eight years of teaching philosophy of language. He writes that students tend to have enormous difficulty understanding its foundational texts. He will therefore explain these texts, assuming no previous familiarity. He hopes his efforts will be useful not just to students but to their professors, saving the latter “arduous exegesis.” Ten texts are explained, though they are not reproduced here; the book is meant to accompany a standard anthology.

The texts, beginning with Gotlob Frege’s 1892 article “On Sense and Reference,” are classics indeed, meaning that anyone wishing to know modern philosophy of language must have mastered them. And they are undeniably difficult. McGinn’s painstaking efforts at unpacking them will surely be, as he hopes, a boon in the classroom. But McGinn is too modest in his aims. I would offer Philosophy of Language as a challenge both to those who think that there is no such thing as philosophical expertise and to those who think there ought not to be. Both biases are refuted by what has been accomplished in the years since Frege’s article first set philosophy of language on its modern track.

What exactly is this modern track? What, to be more blunt, is philosophy of language trying to accomplish? McGinn addresses this blunt question bluntly:

The most general thing we can say is that philosophy of language is concerned with the general nature of meaning. But this is not very helpful to the novice, so let us be more specific. Language is about the world—we use it to communicate about things. So we must ask what this “aboutness” is: what is it and how does it work? That is, how does language manage to hook up with reality? How do we refer to things, and is referring to things all that language does? Further, is referring determined by what is in the mind of the referrer? If not, what else might determine reference? Some parts of language we call “names,” but is everything in language a name? How is a word referring to something connected to a person referring to something? Do expressions like “Tom Jones,” “the father of Shakespeare,” and “that dog” all refer in the same way?

In what way do these types of expressions differ in meaning? How is a sentence related to its meaning? Is the meaning the same as the sentence or is it something more abstract? Can’t different sentences express the same meaning? What is a meaning? Are meanings things at all? How is meaning related to truth? Whether what we say is true depends on what we mean, so is meaning deeply connected to truth? How are we to understand the concept of truth? What is the relationship between what a sentence means and what a person means in uttering a sentence?”

In addition to Frege, McGinn devotes a chapter each to Saul Kripke’s Naming and Necessity, Bertrand Russell’s “Descriptions,” Keith Donnellan’s “Reference and Definite Descriptions,” David Kaplan’s “Demonstratives,” Gareth Evans’s “Understanding Demonstratives,” Hilary Putnam’s “Meaning and Reference,” Alfred Tarski’s “The Semantic Conception of Truth,” Donald Davidson’s “Semantics for Natural Languages,” and H.P. Grice’s “Meaning.” These texts thrust the reader into the core of philosophy of language: theories of reference, of meaning, of truth. They develop a specialized vocabulary to do justice to subtle but indispensable distinctions, starting with the distinction between a sentence, a proposition, and a statement:

Advertisement

A sentence is a collection of shapes, signs, or acoustic signals. Different shapes of letters on paper or acoustic signals in the air can correspond to the same proposition. Propositions, then, are very different from sentences—more abstract than physical. A sentence is the perceptible vehicle that expresses a proposition, and in addition can be uttered by a person. When you utter a sentence like “Snow is white,” you thereby make a statement. A statement is a relationship between three things: the speaker, the sentence, and the proposition.

This standard act of conceptual analysis occurs on the second page of the book, before the discussion of Frege is even attempted, and it gestures toward a truth that is fundamental to analytic philosophy. Clarity and complexity are not antagonists, but rather allies. The pursuit of clarity churns up unexpected complexity, but it can be tamed by the pursuit of further clarity.

Many other classics in the philosophy of language have been omitted, including writing by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Peter Strawson, Michael Dummett, Willard van Ormand Quine, John Austin, Jerry Fodor, and John Searle. Also missing is the work of Noam Chomsky, a linguist whose insights into the mathematical structure of language have had a tremendous impact on the philosophy of language. The intended use for this book has shaped its scope. Philosophy of Language is fitted to the duration of a college semester, but McGinn’s sculpted choice of ten works also forms a narrative arc, allowing the reader to see the cumulative progress of the field. The theories build upon one another in the way that scientific theories do, with the results of one text leading to the ideas of the next. McGinn is very clear in explaining, for example, exactly how Donald Davidson appropriated the insights of Alfred Tarski’s semantic theory of truth for formal languages (the rule-governed systems constructed by logicians to state and prove theorems in logic and mathematics) and adapted them for use in a theory of meaning for natural languages (the languages we actually speak, like Urdu and Spanish, which are richer and wilder than the fastidious language of the logicians).

Philosophical progress is perhaps less accurately measured in the discovery of answers and more in the discovery of questions, which often includes the discovery of the largeness lurking within seemingly small questions. The theories explained by McGinn reveal many prosaic linguistic situations to be perplexingly fascinating.

If, for example, I assert, “The prime minister of the US is six feet tall,” have I said something false, in which case are you to infer that the prime minister of the US is not six feet tall, or have I managed to make no statement at all? Or if, standing at a bar, I remark to my companion, “The man drinking a martini is a famous philosopher,” and it turns out that it is only water in the martini glass, have I managed nevertheless to say something true, if in fact the teetotaler is a famous philosopher? If, when asked to write a letter of recommendation for a student applying for graduate work, I write a letter that speaks exclusively of her excellent handwriting, how have I damned her chances for acceptance, since there is nothing in what I’ve written that says she is not competent for graduate work?

Such questions, removed from their theoretical contexts, may seem too paltry to carry off the grandeur of the genuinely philosophical. And yet a reader giving herself over to McGinn’s explanations will be led to understand how such modest inquiries bear the loftier aims of philosophy of language as he has stated them.

Advertisement

Gotlob Frege’s “On Sense and Reference” is the only text analyzed in the book that was published before the twentieth century. It was the century that saw preoccupations about language engaging the attention of some of the best philosophical minds—many of them on display here—who were most responsible for the shift in approach toward analytic philosophy. Frege’s article is devoted, by and large, to analyzing how the sentence “Hesperus is Phosphorus”—which is true, since the same planet, Venus, is referred to by both names—can be different from the sentence “Hesperus is Hesperus.” The latter is a trivial tautology, while the former is not. These sentences must, therefore, mean different things. But how, exactly, since the terms that differ between them refer to the same thing?

Frege’s article had a galvanizing effect on such philosophers as Bertrand Russell. When the young Russell arrived as a student at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1890, philosophy was dominated by the ponderous metaphysics of German idealism, which pounded out propositions purporting to delve into the murky and nebulous features of “the Absolute.” An older Russell once reminisced that he had thought of language as transparent, the medium of thought that could simply be taken for granted. Frege demonstrated otherwise. Instead of trusting language to transport one into intimacy with the Absolute, it might be good to first discover how language manages to do more basic things, in the manner of Frege. Modern philosophy of language and analytic philosophy were both born in this same technical turn taken by philosophy.

Confusingly, the rising importance of philosophy of language coincided with a movement that argued that all of philosophy should be absorbed into philosophy of language. This latter movement was sometimes called “the linguistic turn” in philosophy. In 1967, Richard Rorty edited a collection of essays written by leading contemporary philosophers and entitled The Linguistic Turn. (He attributes the phrase to the logical positivist Gustav Bergmann.) Whereas philosophy of language is the branch of the discipline that sets itself the problem of understanding truth, meaning, reference, and so on (as in the paragraph by McGinn quoted above), the linguistic turn was a metaphilosophical movement that aimed to demonstrate that all philosophical questions can be solved—or, as these philosophers preferred to put it, dissolved—by attending sufficiently stringently to issues of language. This was a deflationary movement: it sought to use the analysis of language in order to show that there are no genuine philosophical problems. The philosophical urge is less to be cultivated than cured.

To make matters even more complicated, two different schools comprised this deliberately corrosive linguistic turn in philosophy: logical positivism and ordinary language philosophy, the latter often referred to as linguistic philosophy (just to add to the terminological confusion). Both positivism and linguistic philosophy are represented in Rorty’s collection.

Logical positivism rested on a theory of meaning that identified the meaning of a proposition with the empirical conditions that would verify it. So the meaning of the proposition “My wedding band is 14-karat gold” was equated with whatever tests and assays a chemist might use to verify what the ring is made of. If there is no way to verify a proposition, according to this theory, the proposition has no meaning. This had the devastating effect of rendering most of the traditional propositions pondered in philosophy—the nature of morality, or God, or beauty, or that bothersome Absolute—not just difficult, not just unknowable, but meaningless: no different in kind from trying to interpret the lyrics of “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo.”

Linguistic philosophy, in contrast, was insistently antitheoretical, denying that there could be a coherent characterization of meaning in general. Instead, it fractured meaning into the different things we do with language—or, to use the terminology of Wittgenstein’s influential Philosophical Investigations, the different “games” we enact within language. We don’t just try to describe things in the world by using words; we also perform actions, as when I say “I do” under the right circumstances and get myself married; or when I say “I feel your pain” in a gesture of sympathy. Indeed, according to many ordinary language philosophers, even saying “I feel my pain” isn’t an act of straightforward description, as if there is a pain inside me and I am simply pointing to it with words. Naively taking our language at face value leads, they argued, to insoluble problems.

In The Concept of Mind, Gilbert Ryle argued that mentalistic terms like “image” and “idea” hoodwinked us into thinking that they referred to actual things and thereby led to the incoherent belief that a mind existed independently of the brain, the doctrine he memorably ridiculed as “the ghost in the machine.” It’s like my exclaiming, “Oh, for Pete’s sake!” and then being asked not only who Pete is but also what his sake is and where it is kept. And just as our naive swallowing of the language of everyday experience misleads us into asking about a mysterious “mind,” our swallowing the language of morality misleads us into asking about mysterious “values,” and our swallowing the language of mathematics misleads us into asking about mysterious “numbers.” “Philosophy,” wrote Wittgenstein, “is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

It’s easy to confuse analytic philosophy, which emphasizes the philosophy of language, with the metaphilosophical view that promised to dispose of all philosophical problems by rigorously attending to language. Those who bristle at the deflationary claim of the latter often lay their grudge at the feet of analytic philosophy. This is unjust. The technical turn is not the same as the linguistic turn.

Colin McGinn has no truck with the linguistic turn. He is known to have expressed a metaphilosophical view that, while identifying philosophy’s task as the analysis of concepts, is maximally expansive, countenancing even metaphysics, the bugaboo of both positivists and linguistic philosophers. I have spoken of some of the omissions in Philosophy of Language: The Classics Explained, and one can detect a method behind some of the missing. The ten classic works in the book are consistent with McGinn’s expansive view. None of their authors evaded or dismissed the traditional challenge to philosophy of clarifying and perhaps even answering profound questions.

McGinn has put himself at the service of his texts, not ranging beyond exegesis and clipped criticisms. He has also put himself at the service of philosophy of language, not pursuing the implications that the theories might have in other areas of philosophy. In Naming and Necessity, for example, Saul Kripke developed a theory of reference that crucially distinguishes rigid and non-rigid designators, which in turn requires that we think of our actual world as just one of many possible worlds. In the actual world the New England Patriots won the last Super Bowl. But there was nothing necessarily true about their victory: there are possible worlds in which the Seattle Seahawks won. The description “the winners of Super Bowl XLIX” happens to refer to the Patriots, but it does not do so in all possible worlds. This makes “the winners of Super Bowl XLIX” a non-rigid designator: its connection to the Patriots is pliable and bends to attach to different teams in other possible worlds.

A rigid designator, in contrast, inflexibly connects to the same referent in all possible worlds. “The square root of 4” is a rigid designator, referring to 2 in all possible worlds. The distinction has implications that reach well beyond language. Kripke used it to construct startling arguments in metaphysics (resuscitating the ancient notion of an essence—which is that attribute of a thing that makes the thing the very thing that it is), philosophy of mind (reformulating an argument for Cartesian dualism), and epistemology (arguing that scientifically discovered truths like “heat is molecular motion” are, though empirical, also necessarily true).

The achievements of philosophy of language have extended beyond philosophy itself, sometimes to surprisingly practical concerns. Take the philosopher with his water-filled martini glass, which comes from Keith Donnellan’s “Reference and Definite Descriptions.” (Definite descriptions begin with the definite article “the,” and refer, if they refer at all, to no more than one thing.) In the course of explaining how one can successfully refer to an individual using a definite description that doesn’t literally apply to him, Donnellan distinguishes between referential and attributive definite descriptions.

When I use a definite description referentially, I have a specific individual in mind, and my aim is to refer to that individual. So long as I get the listener to know who or what I’m talking about, I’m using the definite description successfully, as I did in singling out the teetotaling philosopher. The specific content of the definite description doesn’t really matter; I’m just using it, in effect, to point. But when I’m using a definite description attributively, the content is precisely the point. The phrase will refer to anything or anybody that uniquely satisfies what it describes, even if I, as the speaker, am ignorant of the referent, as when I say, “The bastard who hacked my computer has made my life a living hell.”

Notice how the intentions of the speaker make a difference as to how the two kinds of definite descriptions function. Certain speech situations yield their meaning without inquiring about speakers’ intentions. We need consult only the semantics of the situation created by the words. But other situations require inquiry into what is called pragmatics, which analyzes both the language employed and the language user’s intentions. Consider that damning letter of reference written for my unfortunate student.

Pragmatics has received increasing attention from philosophers. McGinn obliquely refers to it in the last of his aims for the philosophy of language: “What is the relationship between what a sentence means and what a person means in uttering a sentence?” Every serious novelist pays close attention to this relationship, as does every serious novel reader. So does every legal scholar. How much is the interpretation of the law a matter of semantics—what the words of a law say—and how much is pragmatics—the intentions of the lawmakers when they passed it? Enormously practical outcomes ride on such decisions.

Or consider this real-life version of the teetotaling philosopher. A married man, abandoning his wife, fakes his death. He then illicitly marries again. A contract he has signed in forming a new business stipulates that “the wife of the depositor” shall benefit in the event of his death, and he makes it clear, though, of course, not in writing, that he intends the beneficiary to be the woman he is living with at the time he signs the contract, whom everyone understands to be his lawful wife. The bigamist dies, the proceeds go to his “wife,” until the first shows up and declares herself the rightful beneficiary. Should “the wife of the depositor” be interpreted referentially, and refer to the woman the bigamist intended to indicate with the phrase, or attributively, as the real wife demands? Just such a legal situation arose in 1935, and the majority of the judges decided on the referential interpretation. The philosopher Gideon Rosen has argued that subtle points in the philosophy of language raised by, among others, Kripke, imply that the majority opinion was mistaken.

It was the philosopher H.P. Grice who is most responsible for turning philosophers’ minds toward the messy social-psychological world of pragmatics, analyzing the wealth of meaning that must be gleaned not from the words alone but from the context in which the words are produced, including, importantly, the speaker’s intentions in uttering them, which furthermore take the speaker outside of his own mind and into the minds of his audience. A speaker has intentions regarding what he wants his words to do in the minds of others, and there, according to Grice, is where a sentence’s true meaning should be sought.

Here, too, real-world applications announce themselves, regarding, for example, the interpretation of the Constitution. Should we, as strict constructionists urge us, consider only the semantics of the words themselves in order to interpret the Constitution’s meaning, or must we use pragmatics, too, consulting historians to try to understand the original intentions of the framers? Their intentions ranged over other minds, including, one might argue, ours. Does a Gricean theory of meaning therefore lend support to those who argue for the Constitution as a living document?

Grice’s is the last text explained by McGinn, and in the final pages he ventures beyond philosophy of language into a fascinating discussion of the “language of the brain,” before abruptly cutting himself off. “At this point we stray into the area of philosophy of mind. We are now inquiring into the semantics of thought. That is a subject for another kind of book. What we can say here is that these questions are not going to be easy.”

McGinn has succeeded brilliantly in demonstrating the substantive progress made in philosophy of language, carrying us to the next set of questions, none of which is going to be easy. These questions are not limited to philosophers of language, nor should they be limited to philosophers. Those who value clarity and do not cringe before complexity can help themselves to what has so far been achieved.