1.

Armageddon

It is not quite clear when Europeans woke up to the largest movement of refugees on their soil since the upheavals of World War II, but Sunday, August 16, may have been a decisive turning point. In a television interview that day, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, returning from her summer vacation, said that the European Union’s single greatest challenge was no longer the Greek debt crisis. It was the wave after wave of Syrians and others now trying to enter Europe’s eastern and southern borders. It is “the next major European project,” she said. It “will preoccupy Europe much, much more than…the stability of the euro.”

In the capitals of Western Europe, Merkel’s words seemed to come as a surprise. And yet across a long corridor of countries, from the Anatolian coast to Greece on up to Hungary and Austria, for anyone who cared to notice there were Syrians waiting to pay human smugglers in back alleys of Turkish beach towns. They were clinging, in the darkness, to hopelessly unseaworthy dinghies in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas; crouching in groups, thirsty and sunbaked, in trash-strewn holding areas on the Greek island of Kos; clamoring to get on rusty trains in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia; trudging, in irregular lines, with young children on their shoulders, through the forests of the Serbian–Hungarian border. They were emptying their last savings so they could again pay smugglers to be stuffed into the backs of trucks for a harrowing journey further north to Vienna or even to Munich.

In fact, the new wave had already begun in late spring, when hundreds of thousands of Syrians, Iraqis, and Afghans began crossing from Turkey to Greece and continuing, as best they could, into Central Europe. Though it was little noted at the time, by July, well over a thousand people were arriving every day in the Greek islands closest to Turkey, which were woefully ill-equipped to receive them.

International aid workers said that some holding areas had now become the most squalid in the world. At Kara Tepe, a makeshift reception center on the island of Lesbos, the International Rescue Committee, an emergency aid group working in forty countries, reported that there were just two showers for two thousand refugees; the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) described conditions as “shameful.”

Three days after Merkel’s comments, German Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière revealed that more than three quarters of a million Syrians and others were now expected to seek asylum in Germany alone this year—a four-fold increase from 2014. (The figure has since been revised to one million.) “It will be the largest influx in the country’s postwar history,” de Maizière said. Nor was this a temporary situation, he said. With a record 60 million people currently uprooted by war and instability around the world—many of them on Europe’s perimeter in the Middle East and Africa—this level of flow was likely to continue for years to come.

In the days and weeks since Merkel’s comments and de Maizière’s press conference, Europe has been transfixed by a problem so vast and so politically charged that it seems to have exposed all the fault lines of the European project. For years, the European Union has struggled to create a uniform system for dealing with people who arrive on its shores seeking a safe haven. Formally, such people are not “refugees” but rather “asylum seekers” who must apply for asylum after arriving in Europe.

According to a flimsy system known as the “Dublin rules,” after the 1990 Dublin Convention on asylum, you are supposed to apply for protection in the first EU country you enter. In practice, because there is free internal movement in the EU and no mandated sharing of responsibilities among member states, these rules are unenforceable.

The poorer Mediterranean countries, such as Greece, where asylum seekers enter the continent, tend to provide as little help as possible and look the other way as the newcomers head further north. Their counterparts in Central and Northern Europe adopt ever more restrictive asylum policies. As a result, the burden has fallen on the very few countries that have been willing to take in large numbers of refugees. In 2014, nearly half of all asylum seekers in the twenty-eight EU countries applied for asylum in Germany and Sweden. This was the situation that this summer’s influx brought precipitously to a breaking point.

Even as Germany said it would continue to open its doors wide, its wealthy neighbor Denmark cut benefits to refugees in half and took out English- and Arab-language ads in newspapers in Lebanon—where there are more than 1.5 million Syrian refugees—telling prospective asylum seekers not to come. Even as Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven said, “My Europe takes in refugees. My Europe doesn’t build walls,” Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán said his government was completing just such a wall, a 110-mile razor-wire fence designed to keep out refugees trying to cross the border from Serbia. And while the French government has announced that it would take in 24,000 of those now seeking refuge in Europe to ease the burden of its neighbors, the British government has refused to do likewise, maintaining that any accommodation of asylum seekers would only encourage more to come. (Britain has instead pledged to take in 20,000 Syrian refugees over the next five years that it will select directly from the Middle East.)

Advertisement

Among European politicians and the media, there has been a perplexing confusion about who the newcomers are. Chancellor Merkel has unambiguously described them as “refugees” (Flüchtlinge), a usage adopted by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker that clearly befits the UN refugee agency’s finding that more than 90 percent of the current wave come from Syria and other refugee-producing countries. Yet other European leaders have referred to them as “migrants,” or even “illegal migrants,” a wording that obscures entirely the horrors of war they are trying to escape. For its part, the international press has offered little clarity, with the BBC, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times mostly opting for “migrants,” and the Financial Times using “refugees” and “migrants” interchangeably; The Guardian is one of the few major news organizations to refer consistently to a “refugee crisis.”

Countries in Eastern Europe, especially, have portrayed the influx as a security threat. In the Czech Republic, police have been taking refugees off trains, detaining them, and even, in one case, writing numbers on their arms; in Slovakia, the government has said it would accept only Christian refugees, warning of the dangers posed by “people from the Arab world.” In both Hungary and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, which is not a member of the EU but on the main land route to Serbia and Hungary, police have fired tear gas at Syrians trying to cross their frontier. In a speech to the House of Commons on September 7, British Prime Minister David Cameron introduced a further element. Speaking of “the migration crisis” amid a discussion of national security, he referred to “Islamist extremist violence.”

Across the continent, strong humanitarian impulses have competed with growing fears about the absorption of large numbers of Muslims. At train stations and public parks, citizens and municipalities have spontaneously offered food, water, clothes, and shelter; in Scandinavia in late August, I met activists who, dismayed at their own governments’ response, were organizing a kind of underground railway to help refugees get from one country to another—even if it meant breaking the law. And yet anti-immigrant parties have also gained record strength in Sweden and France. Asylum centers have been targeted by arsonists in Germany; and numerous politicians, from Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary to Denmark and the Netherlands, express misgivings about what Dutch populist Geert Wilders, speaking in his national parliament in early September, called an “Islamic invasion.”

The movement to Europe should not have come as a surprise. According to the UN, in 2014 a record 14 million people were newly forced from their homes in armed conflicts worldwide, and much of the staggering increase was owing to the wars in Syria and Iraq. In Syria, more than half of the total pre-war population of 22 million was now uprooted. With the ravages of barrel-bombing by the Assad regime, the terror of the Islamic State, and the growing inability of the international community to deliver aid inside the country, more Syrians than ever before sought refuge abroad.

In the first four months of 2015 alone, another 700,000 fled, many to nearby countries, the highest rate of any time during the war. Meanwhile, Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, already overwhelmed with millions of Syrians, have been restricting entry, while the underfunded World Food Program has been drastically reducing food aid.

Other recent developments, though less noticed, had far-reaching effects of their own. Several countries in Africa, including Libya, and also many parts of Afghanistan, traditionally the world’s number one producer of refugees, have become increasingly unstable and violent in the months since international forces withdrew from Afghanistan in 2014. At the same time, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey, which had together absorbed more than five million Afghans in recent years, had begun taking aggressive steps to send them home or prevent them from staying; by this summer, tens of thousands of Afghans were joining the Syrians trying to enter Europe.

For the refugees themselves, the journey to Europe—requiring a series of up-front payments to smugglers of human beings, often amounting to several thousand dollars—is enormously costly and fraught with danger. More than 2,800 people have drowned trying to cross the Mediterranean in 2015 alone. Others have fallen sick or died in encampments in Greece or in the backs of trucks in Central Europe.

Advertisement

On August 27, Austrian police found an abandoned Volvo refrigeration truck packed with the bodies of seventy-one refugees who had paid smugglers to drive them from Hungary to Austria but had suffocated en route; a day later, Austrian police stopped another smuggler’s truck containing twenty-six refugees, including three children who had to be hospitalized for severe dehydration. And yet, every day, thousands more have set out from Turkey for the Greek islands, including the young Syrian boy Aylan, whose lifeless body washed up on shore in Turkey after a failed crossing on September 2, shocking the world.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan accused Europe of turning the Mediterranean into a giant cemetery; Andreas Kamm, the longtime director of the Danish Refugee Council, said that, without major changes, Europe’s incoherent response was headed toward “Armageddon.” For her part, Chancellor Merkel said that, unless other member states were prepared to step up and share the burden, the very basis of the EU and its Schengen system of open internal borders would be at risk of collapse.

On September 9, EU President Juncker asked member states to adopt a bold plan to distribute 120,000 of the new arrivals as well as 40,000 that had arrived earlier in the year equitably among each of them. This would by no means address the overall numbers arriving, but it would set an important precedent for collective responsibility. By this point, however, the extraordinary numbers of refugees crossing into Bavaria were already moving events in an alarming new direction. Unable to cope, Germany imposed temporary emergency border controls on its Austrian frontier. This radical step, effectively suspending the Schengen system, precipitated similar moves by Austria and Slovakia—and then by Slovenia and Croatia, which had suddenly become alternate routes into the EU. Hungary, meanwhile, which sealed its border with Serbia on September 15, was firing tear gas, water cannons, and pepper spray at refugees, and arresting those who made it across.

With thousands of people now massed on the EU’s borders, and with fall rains and colder weather approaching, the closures threatened to create a new humanitarian crisis of their own; the UN Refugee Agency accused Hungary of violating the basic protections set out in the 1951 Refugee Convention. Above all was the deplorable situation of Greek islands like Lesbos, where there were now 20,000 or more refugees, many lacking any form of shelter.

On September 22, against strenuous opposition from Eastern European countries, the EU adopted mandatory quotas for relocating 120,000 refugees now in Italy, Greece, and Hungary. But at an emergency summit the following day, EU heads of state were mainly focused on ways of controlling EU borders.

Why, given the manifestly urgent needs of those now arriving, did European leaders seem so ambivalent about helping them? And why was the political response so closely tied to border security and strong-armed police tactics?

2.

Is It Illegal to Be a Refugee?

At the heart of the current crisis is a fundamental problem: there are virtually no legal ways for a refugee to travel to Europe. You can only apply for asylum once you arrive in a European country, and since the EU imposes strict visa requirements on most non-EU nationals, and since it is often impossible to get a European visa in a Middle Eastern or African country torn apart by war, the rules virtually require those seeking protection to take a clandestine journey, which for most would be impossible without recourse to smugglers. This situation has led to a vast, shadowy human-smuggling industry, based in Turkey, the Balkans, and North Africa, which European officials have recently estimated to be worth as much as $1 billion per year.

Just months before the current refugee crisis erupted this summer, European leaders launched a “war on smugglers,” a controversial plan to crack down on criminal networks in Libya that control what European officials call the “Central Mediterranean” migration route. As Libya descended into growing instability and violence following the 2011 revolution, it became a haven for human smugglers, who specialize in ferrying asylum seekers to Lampedusa, off the coast of Sicily. The smugglers are paid upfront and do not themselves navigate the boats; they have every incentive to put as many people as they can onto small, wooden crafts, leaving it to Italian and European naval forces to rescue them when they founder. (According to European security experts, the smugglers offer a “menu” of different levels of service for these terrifying journeys, charging more if you want to have a lifejacket, or to sit near the center of the boat, where you are less likely to wash overboard.)

This is not a new phenomenon: the Missing Migrants Project, a database run by the International Organization of Migration in Switzerland, has recorded more than 22,000 migrant deaths in the Mediterranean since the year 2000. But over the past eighteen months, as demand has gone up and smugglers have grown more reckless, the number of fatalities has increased dramatically, with more than five thousand deaths since the beginning of 2014. This year, in the month of April alone, a record 1,200 people are believed to have drowned off the coast of Libya. “How many more deaths will it take for us to call these guys [i.e., the smugglers] mass murderers?” a migration official for a Northern European government told me. In late September, the UN Security Council was to vote on a draft resolution authorizing European forces to seize and even destroy smugglers’ boats off the coast of Libya.

“It was a mess,” the migration official said. “Here we were trying to deal with smugglers and migrants, and suddenly you had this huge batch of legitimate refugees in Greece.” In fact, a great many of the people on the Libyan boats were also refugees, fleeing conflicts in Eritrea, Sudan, Libya, and elsewhere. But the situation was generally portrayed as a “migrant boat” problem, and in late April the European Council announced a plan for “fighting traffickers.” (In fact, human trafficking is the coercive transfer of people for slavery, forced labor, or exploitation, and there is no evidence that asylum seekers are being brought to Europe against their will.)

The Syrians arriving in Europe in recent weeks have been equally dependent on smuggling networks. In the past, the “Western Balkans” migration route, which since 2008 has been the second most common path to Europe after the Central Mediterranean route, often involved crossing Turkey’s land border with Bulgaria. In 2014, however, the Bulgarian government started building a border fence to keep out growing flows of asylum seekers, and smugglers shifted their attention to sea routes across the Aegean.

In immigrant neighborhoods of Istanbul, and in the backstreets of the resort towns of Izmir and Bodrum, smuggling outfits have been using Syrians and other Arab speakers to promote crossings in inflatable rubber dinghies to one of the Greek islands only a few miles off the Turkish coast. For €1,000 or more, you can buy a spot in a dingy with as many as seventy other people to try to reach Kos or Lesbos; if you make it, you must then join the thousands of Syrians and others vying to get on one of the large car ferries Greek officials have occasionally used to ship refugees from the islands to the Greek mainland. Until the recent border closures, you could then, by paying smugglers, continue through Macedonia and Serbia to Hungary. According to Frontex, the European border control agency, in the second quarter of 2015, the number of people entering Europe this way had risen more than 800 percent since last year.

In a recent investigation, Der Spiegel reported that the smuggling organizations in Turkey tend to be run by Turks and Kurds and often employ “dozens of recruiters, financiers, drivers and guards” of various nationalities. In the Balkans, major smuggling rings have been observed working from a hotel near the train station in Belgrade and from bases in Budapest; many of the drivers, who can earn up to several thousand euros a day, are believed to be Bulgarians. (Three of the five suspects in the deaths of the seventy-one refugees in the truck in Austria were Bulgarian nationals, including one with a Lebanese background; a fourth, who is believed to have been the ringleader, was an Afghan with a Hungarian residency permit.)

Syrians carry lists of smugglers’ phone numbers for use at every stage of the journey; with so much demand, prices have risen rapidly. Earlier in the summer, Der Spiegel reported, the 125-mile trip from Belgrade to the Hungarian border could be arranged for €1,500.

Already anticipating the recent closure of the Hungarian border, smugglers have long been exploring alternative ways to reach Northern Europe. According to the German newspaper Die Welt, one of the pioneers of a bold new strategy is a thirty-five-year-old Syrian smuggler based in Mersin, on the southern Turkish coast near the Syrian border. Last winter, working with two business partners and a staff of fifteen, he began using large container ships to send hundreds of refugees at a time from Mersin all the way to Puglia on the east coast of Italy. In its Annual Risk Report this year, Frontex describes this innovation as a “multi-million-euro business” that is “likely to be replicated in other departure countries”:

The cargo ships, which are often bought as scrap, tend to cost between EUR 150,000 and 400,000. There are often as many as 200–800 migrants on board, each paying EUR 4,500–6,000 for the trip, either in cash a few days before the departure or by Hawala payment after reaching the Italian coast. The cost is high because the modus operandi is viewed as being safe and has been demonstrated as being successful. Hence, the gross income for a single journey can be as high as EUR 2.5 or even 4 million depending on the size of the vessel and the number of migrants on board. In some cases, the profit is likely to be between EUR 1.5 and 3 million….

A tragic aspect of the burgeoning industry is the extent to which it has seemed to taint the refugees themselves. Part of British Prime Minister David Cameron’s rationale for refusing to take part in a European plan to redistribute asylum seekers, for example, was that the new arrivals were associated with a seamy underworld. Elizabeth Collett, the European director of the Migration Policy Institute in Brussels, told me, “The British were saying, ‘We don’t want to reward people who we believe have taken matters into their own hands’” by getting smuggled into Europe.

In fact, because of the costs involved, the bar to setting out to Europe is already high, and many of the Syrians I have met are well-educated doctors, engineers, and urban professionals who no longer see any future in Syria or the surrounding region. For these Syrians, the continual dance between exploitative smugglers and hostile European authorities has often seemed baffling. Here is the account of one thirty-four-year-old Syrian man who recently made the crossing to Lesbos and was interviewed by the International Rescue Committee:

The journey costs $1,125 [USD]. You pay the money to a broker in Izmir. You give him the money and they give you a secret number. You give this number to the smuggler when you reach the boat, so they can collect the money….

I saw the boat was a dinghy. It only seated 40 people but there were 54 of us. The smugglers had lied. They only want to get your money. They don’t care if you die.

We travelled on the sea for an hour. We then came across another boat. We didn’t realise it was the police. We were told by friends not to stop because they will take you back to Turkey. We don’t know the Greek language. We can’t understand what they are saying. They were saying stop the boat.

We held the children and we shouted at the police, “We have children!” …The boat was punctured and we fell in the water. I was in the sea for 45 minutes before they pulled me out….

They helped us ashore. But why are they doing it this way? Don’t help us the hard way. Help us the easy way.

3.

A Worldwide Conflict

Rather than treating Syrians as a security threat or a humanitarian “burden,” some economists, including Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann and the French scholar Thomas Piketty, argue that Europe should simply put them to work. Germany in particular, with the lowest birthrate in the EU, desperately needs workers. In 2014 it launched a program to put migrants and refugees directly into the labor market and German officials hope that the incoming Syrians will quickly find jobs. But David Miliband, the former foreign secretary of Great Britain and the current head of the International Rescue Committee, told me that this approach may be a hard sell in other European countries. “There is certainly not a demographic time bomb [i.e., a threat of dwindling workforce] in the UK,” he said, noting that many Eastern European workers came to Britain in the mid-2000s.

Elizabeth Collett, the migration expert, suggested that the economic calculation is a crucial part of Europe’s refugee dilemma. “One of the questions we’ve yet to answer is what is the goal of the asylum process: Is it about giving people an opportunity to a new start in life? Or is it about offering temporary protection during a crisis?”

UN officials and international aid groups say that the EU may have to end the disastrous Dublin rule requiring refugees to apply for asylum in the “country of first entry” and change its visa policies if it is to begin to provide a safe, legal way in for those fleeing war. It will also have to work more closely with the UN refugee agency itself, which has long sought to send refugees most in need directly to Western countries. Though it is a big, lumbering bureaucracy, the UNHCR has already registered more than four million Syrian refugees in the Middle East since 2011; if European nations were to start accepting large numbers of them, fewer Syrians might be tempted to pay smugglers to cross the Aegean. Until now, only a few European countries have been accepting UNHCR refugees, and the process can take years.

For its part, the United States has belatedly said it would take in more Syrians, raising its pledge to 10,000 UN-designated refugees. On September 20, Secretary of State John Kerry said the US would also raise the overall annual cap on the number of refugees it accepts from all countries from 70,000 to 100,000 by 2017. But many, including Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois, say the US should be taking in 100,000 Syrians alone; as of September, only about 1,500 had been admitted.

David Miliband, who calls the American contribution “paltry,” said, “How is it that the US has gone from being the world’s leader on this to being outflanked eight-hundred-fold by the Germans?”

No amount of resettlement, however, will mitigate the continued failure of the United States and its European allies to address the refugee crisis at its source. Already in 2013, Syria had produced the largest humanitarian catastrophe of our time. One third of its population had been chased from their homes; as many as half of those taking flight were children. And yet as the war became even more violent, the international community largely turned its back on them. In 2013, 71 percent of the amount needed for humanitarian aid for Syrians was raised; in 2014, the figure fell to 57 percent; this year, it stands at just 37 percent. According to the UN, as many as five million people are now stuck in “hard to reach areas” of Syria and not getting any aid at all.

The refugees now fleeing to Europe, Pope Francis recently said, are the “tip of the iceberg.” A report released by the UNHCR in June suggests he is right. Called World at War, it documents what António Guterres, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, describes as “an unchecked slide into an era in which the scale of global forced displacement as well as the response required is now clearly dwarfing anything seen before.”

For much of the decade before 2011, global figures for displaced people were relatively stable; between 2011 and 2014, they rose 40 percent. 2014 was the highest annual increase on record; 2015 may be even higher. Behind this are a record number of simultaneous civil wars—from Syria, Iraq, Eritrea, and Afghanistan to South Sudan, Yemen, Ukraine, Central African Republic, and Somalia—many of them now continuing for a decade or more.

Andreas Kamm, the director of the Danish Refugee Council, told me that we are witnessing a “worldwide conflict” in which the main victims are civilians who are no longer able to escape:

For Europe the numbers are not that high. If we had leaders who could work together and say, we will do things better, we can manage it—one million refugees is only 0.2 percent of the European population. But if we do nothing, people will say, it’s out of control. And then it is [out of control]. That’s what scares me.

—September 23, 2015

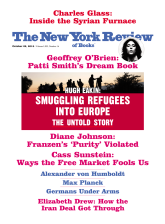

This Issue

October 22, 2015

The Very Great Alexander von Humboldt

Her Private Papers