The first Republican presidential primary debate on August 6 will be remembered for Donald Trump’s exchange with moderator Megyn Kelly about his retrograde attitudes toward women, but the debate’s most significant moment came in a different exchange altogether, between Trump and another moderator, Bret Baier. Baier asked Trump about his reported donations to liberal politicians, Hillary Clinton and Nancy Pelosi—donations that might be seen as disqualifying to loyal Republican primary voters. Trump brushed aside the question, explaining: “I give to everybody. When they call, I give. And do you know what? When I need something from them two years later, three years later, I call them, they are there for me.” The truth of this comment was so evident that no one on the stage even took Trump to task for supporting the enemy. That’s just how the game is played. Rich people give money to candidates so that they can demand favors from them two or three years later. Next question, please.

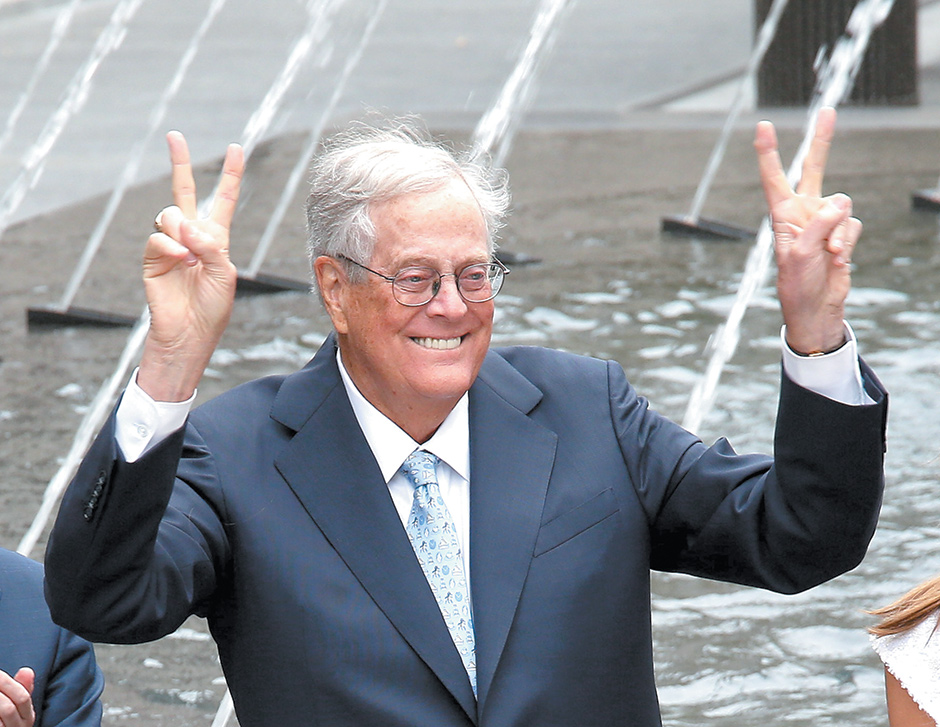

In the midst of a presidential campaign, our democracy is in shambles. That Donald Trump, after loaning his own campaign $1.8 million in the second quarter of 2015 alone, has risen so far in the polls is itself a telling commentary on the electoral process. The conservative billionaire Koch brothers have committed to spending more money in the presidential campaign than either the Republican or Democratic Party spent in the last one. By August 1, Hillary Clinton had already amassed a campaign fund of nearly $70 million, and Jeb Bush had over $120 million.

As Burt Neuborne, a professor at NYU Law School, puts it in his important and timely book on the First Amendment, Madison’s Music, the super-rich, the wealthiest one to two percent, “set the national political agenda, select the candidates, bankroll the campaigns…, and enjoy privileged postelection access to government officials.” The rest of us are left to “navigate among the choices made available” by the super-rich.

Only about 40 to 60 percent of citizens vote in any given presidential election. The rest, who are disproportionately poor and members of minorities, do not even participate. Some are impeded from voting by unnecessarily stringent registration and voter identification requirements as well as narrow time windows for voting, long lines, and other obstacles. Many others have likely concluded that in view of the outsized influence of the rich, their votes wouldn’t matter.

At the same time, increasingly sophisticated gerrymandering has ensured that many elected offices are sinecures for one of the two major parties. In the House of Representatives, only about forty seats, or less than 10 percent of the chamber, are filled in genuinely contested general elections. The results can be perverse. In North Carolina in 2012, the popular vote for House members was 51 percent Democratic and 49 percent Republican. Yet North Carolina’s delegation to the House consisted of nine Republicans and four Democrats. North Carolina’s state legislature had packed Democratic voters into four districts, ensuring that Republicans would win the other nine. As a result of such manipulation, Neuborne writes, “not a single contestable election takes place in a closely divided state.” Democrats received more than half of House votes in Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in 2012, and did not get a majority of House seats in any of them. In what sense can such outcomes be called democratic?

According to Neuborne, the Supreme Court bears much of the blame for the depressing state of our democratic process. He is particularly critical of its decisions in Buckley v. Valeo, which allowed individuals to make unlimited expenditures on campaigns, and Citizens United, which ruled that corporate expenditures on political campaigns count as exercises in freedom of speech under the First Amendment and likewise may not be limited. As he sums it up:

In the dysfunctional democracy the justices have built, at least one half of the electorate doesn’t vote, the Supreme Court gets to pick a president, the extreme wings of each major party dominate the nominating process, minor parties are rendered powerless, rich ideological outliers control the political agenda, voting can be an ordeal, lobbyists treat elected officials as wholly owned subsidiaries, and rivers of money flowing from secret sources have turned our elections into silent auctions.

But are all these failures of democracy the fault of the Supreme Court? And would an alternative reading of the First Amendment solve them? That is what Neuborne argues in his sweeping indictment of the Court’s jurisprudence, which combines a rich understanding of the constitutional complexities with a gift for explaining clearly their consequences. If one wants to understand what ails us in this all-too-dispiriting presidential campaign season, there are few better places to start. And Neuborne’s effort to transform the First Amendment from an obstacle to electoral reform into a mandate for such reform is bold and masterful. But while his portrait of the ills of our political system is trenchant and convincing, it will take a lot more than a rereading of the First Amendment to cure what ails us. The problems are deep-rooted, and the answers are not as self-evident as Neuborne sometimes suggests.

Advertisement

The First Amendment protects a series of distinct rights:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Neuborne’s central insight is that when read together, these rights describe “the arc of a democratic idea—from conception to codification.” The amendment opens by protecting the realm of conscience, where normative ideas develop and are fostered. It then protects, in order, the right of speakers to communicate those ideas to others, the right of a free press to distribute the ideas on a mass scale, the right to collective political action through assembly, and finally, the right to submit one’s political demands to the government by means of a petition. In Neuborne’s view, the Court has too often focused exclusively on the right of free speech without adequate consideration of how its rulings affect the workings of democracy overall, a central concern of the amendment as a whole. As a result, he charges, its decisions have often undermined democracy in the name of protecting speech.

Exhibit A in this critique, as in many contemporary criticisms of the Court’s First Amendment rulings, is Citizens United. But Neuborne identifies many other errors as well. The Court’s Buckley v. Valeo decision in 1974 upheld limits on direct contributions to candidates while striking down limits on how much individuals or candidates themselves can spend on campaigns. Neuborne notes that this created “a campaign finance system that no rational person would have chosen and that not a single member of Congress had supported.”

Neuborne is also critical of Supreme Court decisions barring “blanket primaries,” in which individuals can vote across party lines. The Court was also wrong, he asserts, to strike down an Arizona public funding system that tied a candidate’s public funding to the amount his opponent had raised. And in his view, the Court has wrongly declined to invalidate partisan gerrymanders.

The Court should not have struck down a part of the Voting Rights Act that required states with histories of discrimination to “pre-clear” changes in election rules with the Justice Department. And the Court erred in nullifying efforts to draw district lines to increase minority representation, and in upholding voter identification and preelection registration requirements. Together, he maintains, these decisions have created a system in which there are too few genuinely contested elections, while rich individuals and corporations exercise disproportionate influence, and poor people often do not participate at all.

These errors might have been avoided, Neuborne argues, had the Court recognized that the First Amendment’s aim is not merely to protect speech, or religion, or assembly—but to facilitate democracy. The Court should ask in each case whether a law is “good or bad for democracy,” and should recognize in the First Amendment an implied “right to vote, run for office, and receive fair legislative representation.”

It is not clear, however, that acknowledging the First Amendment’s connection to democracy would resolve all the problems Neuborne identifies. The Court has long understood the link between speech and self-government. Justice Louis Brandeis famously did so in an oft-quoted concurring opinion in Whitney v. California in 1927, writing that the First Amendment’s framers

believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that, without free speech and assembly, discussion would be futile; that, with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government.

That the First Amendment was designed to promote democracy, however, does not dictate what rules best further that end, or how to balance the difficult dilemmas presented by electoral regulation. Neuborne, for example, criticizes the Court’s conclusion in Buckley v. Valeo that limits on a candidate’s campaign spending should be viewed as limits on the candidate’s speech. Spending, he argues, is conduct, not speech, and should be more easily regulated. But it costs money to speak, and because campaign finance rules by definition limit only expenditures expressing a political message, they deserve particularly careful judicial scrutiny. A limit on how much one could spend advocating about climate change would warrant close scrutiny as in effect a content-based limit on speech; so, too, should a limit on campaign expenditures.

Advertisement

Moreover, a legislature that was free to impose unreasonable limits on campaign spending could lock in the advantage of its own incumbents. As Neuborne acknowledges, “no savvy incumbent politician designs a district he can lose.” Similarly, savvy incumbents can be counted on to regulate spending in ways that favor their reelection. Indeed, Neuborne himself criticizes the campaign finance law under review in Buckley for seeking “to purge almost all money from elections, a ‘reform’ that just happened to coincide with the best interests of powerful incumbents.”

Thus, careful scrutiny of limits on campaign spending is essential. Directing the Court to ask what is “good or bad for democracy,” moreover, does not answer the question, since reasonable people can and do differ about what rules work best for democracy. Reasonable people also differ about the competing risks of, on the one hand, protecting incumbents by limiting campaign spending and, on the other, giving disproportionate advantages to wealthy candidates and unfair influence to big spenders.

Nor does attention to the value of democracy dictate different results in the other cases Neuborne criticizes. “Blanket primary” rules allowing all voters to take part in selecting a party’s candidate, regardless of their affiliation, may well increase the numbers of people voting, but they also interfere with the rights of political parties to choose their own candidates, a right that would seem to be encompassed in the First Amendment’s right of free association and certainly favors democracy. And if the public funding of a candidate’s opponent is tied to the amount that the candidate raises, is it wrong to view that scheme as penalizing the candidate for raising money? If there are ways to provide public funding that do not penalize an opponent’s own fund-raising efforts, and there are, shouldn’t states be required to adopt those methods instead? Neuborne himself suggests two methods for public financing of elections that would pass constitutional muster: giving everyone a $250 tax credit for campaign spending, or creating generous public matching grants tied to small contributions, as New York City offers.

Emphasizing the First Amendment’s democratic purpose also does not require a different result in disputes over gerrymandering. The Court has been understandably reluctant to wade into controversies over political gerrymandering, both because such cases risk politicizing the Court, and because the choice to allow legislatures to draw districts means that the lines they choose will inevitably be partisan at least in some measure. Identifying when a redistricting map is “too partisan” is no simple matter. The First Amendment does not offer much assistance in identifying impermissibly gerrymandered districts, even as Neuborne reads it.

Nor does that amendment really help the Court decide when districts drawn to maximize a racial minority’s representation should be tolerated under the equal protection clause. A district that ostensibly favors black representation, by concentrating a majority of black voters in one district, may undermine black representation overall by freeing up the rest of the state’s representatives to disregard African-Americans’ interests. Here, too, there are reasonable competing views about what is best for democracy, and the First Amendment does not provide a ready answer.

Neuborne is surely right that the current system is broken. His cogent criticisms of the status quo demand our consideration. But the answer does not lie solely in the retrofitting of First Amendment doctrine, and the solution does not lie exclusively with the Supreme Court. The core of the campaign finance problem, for example, as Neuborne correctly notes, is that “we have decided to treat the necessary costs of operating a complex democracy as an off-the-books expense to be borne by rich volunteers.”

If public funding of campaigns were adequate, many of the wealth problems would go away. But Neuborne does not suggest that the First Amendment demands public funding, or that the Court could or should read it to impose such an obligation. Rather, we the people must choose to make it so. A big part of the solution lies in our hands. What is most needed is a political response: an organized demand from the people for a robust system of public financing.

First Amendment doctrine is undoubtedly part of the problem, and a Court that took more seriously the impact of various rules on our democracy would almost certainly be more open to reasonable limits on campaign spending. The most fruitful avenue for constitutional law reform on campaign finance, however, does not lie as Neuborne implies in rejecting the rulings that limits on campaign spending implicate speech rights, or that corporations have such rights.

Rather, the solution is to be found in a more expansive conception of the permissible justifications for state and federal regulation of such spending. The current Court’s view is that the only justifiable basis for regulating campaign spending is to prevent “quid pro quo” corruption or its appearance—namely, bribery. But Justice John Paul Stevens, Zephyr Teachout, and Lawrence Lessig, among others, have convincingly argued that this is a far too limited conception of “corruption.”1 Corruption of the democratic process also occurs when, even without bribes, spending practices lead elected representatives to serve not “the people” but their biggest donors. Deeming that sort of corruption a legitimate target of campaign spending laws would afford legislatures more leeway to regulate in the name of a fair and equitable political process. A legislature could, for example, impose reasonable caps on campaign expenditures by individuals and businesses alike. Judicial review of such rules will always be necessary in view of the inherent risk that limits on spending will protect incumbents, but the Court’s current crabbed definition of corruption has imposed a too-confining straitjacket, ruling out any expenditure limits at all.

Still, the real impetus for electoral reform, at both the constitutional and statutory levels, must come from the people. Lessig, a professor at Harvard Law School, has sought to inspire a movement for campaign finance reform, and has now entered the presidential race as a means of spreading the word. Teachout, a professor at Fordham Law School, ran for governor in New York on a similar platform, and did surprisingly well against Andrew Cuomo. Hillary Clinton, herself a beneficiary of the wealthy, has nonetheless called for sensible reforms. A number of civil society organizations, including Common Cause, the Brennan Center for Justice (of which Neuborne is the founding legal director), the Campaign for Accountability, 99Rise, Public Citizen, and Demos, to name just a few, have taken on the issue of campaign finance reform. A CBS/New York Times poll in May 2015 found that more than 80 percent of respondents think the role of money in political campaigns is excessive, and that the campaign finance system needs either “fundamental changes” or to be “completely rebuilt.”2

Nearly everyone recognizes that there is a problem. The challenge is to mobilize that sentiment effectively for the long struggle needed to bring about sensible campaign reform. It should not require a constitutional amendment; there are important changes that can be put in place short of that. As a start, President Obama could require government contractors to disclose their campaign expenditures. More robust public financing can be established by the states or Congress. And the Supreme Court should be urged to acknowledge that countering the outsized influence of the wealthy is a justification for reasonable limits on campaign spending.3

While it does not provide all the answers, Neuborne’s elegant book helps identify one source of the problem, and provides an important guide, grounded in the First Amendment itself, for those working toward an electoral system more deserving of the label of democracy.

-

1

See Justice Stevens’s dissent in Citizens United v. FEC; Zephyr Teachout, Corruption in America: From Benjamin Franklin’s Snuff Box to Citizens United (Harvard University Press, 2014); and Lawrence Lessig, Republic, Lost: The Corruption of Equality and the Steps to End It (Twelve, 2015). See also my review of Teachout’s book in these pages, September 25, 2014. ↩

-

2

“Americans’ Views of Money in Politics,” The New York Times, June 2, 2015. ↩

-

3

For an excellent discussion of some existing reform proposals, see Elizabeth Drew, “How Money Runs Our Politics,” The New York Review, June 4, 2015. ↩