In his book On Late Style, published after his death, the critic Edward Said ponders the aura surrounding work produced by artists in the last years of their lives. He asks: “Does one grow wiser with age, and are there unique qualities of perception and form that artists acquire as a result of age in the late phase of their career?” He considers the idea that some late works possess “a special maturity, a new spirit of reconciliation and serenity often expressed in terms of a miraculous transfiguration of common reality.” Yet he also questions the very notion of late serenity: “But what of artistic lateness not as harmony and resolution but as intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction? What if age and ill health don’t produce the serenity of ‘ripeness is all’?”

Said further ponders, as must anyone who thinks about this subject, the sheer strangeness of Ludwig van Beethoven’s late string quartets and his last piano sonatas, their insistence on breaking with easy form, their restlessness, their aura of incompletion (especially the piano sonatas), the feeling that they are striving toward some set of musical textures that have not yet been imagined and cannot be achieved in Beethoven’s lifetime. In other words, it is that these late pieces wish to represent the mind or the imagination not as it faces death but rather as it faces life, as it sets out to reimagine a life with new beginnings and new possibilities but also with the ragged sense that there might not be much time.

Said quotes Theodor Adorno on late Beethoven: “Touched by death, the hand of the master sets free the masses of material that he used to form; its tears and fissures, witnesses to the final powerlessness of the I confronted with Being, are its final work.” As Said would have it, Adorno does not see late style as a departure. Rather, “lateness includes the idea that one cannot really go beyond lateness at all, cannot transcend or lift oneself out of lateness, but can only deepen the lateness.” Finally, Said demands that we read late work with due subtlety, noting continuity as much as rupture, noting a deepening of something rather than a new departure. “As Adorno said about Beethoven,” Said writes, “late style does not admit the definitive cadences of death; instead, death appears in a refracted mode, as irony.”

Two weeks before he died, as his heart was failing, the poet W.B. Yeats wrote a poem he titled “Cuchulain Comforted,” which begins with a set of clear statements free of metaphor, tonally stark, sharp, and pointed almost like the arrows that appear in some of Francis Bacon’s work. The poem was written in terza rima, a form new to Yeats. Unusually for his work, this poem did not need many drafts. It seemed to have come to him simply, easily, almost naturally. In earlier Yeats poems and plays, Cuchulain, a figure from Irish mythology, had appeared as the implacable and solitary hero, prepared for single combat, free of fear. Now he has “six mortal wounds” and is attended by figures—Shrouds—who encourage him to join them in the act of sewing rather than fighting. They let him know that they themselves are not among the heroic dead but are “Convicted cowards all by kindred slain//Or driven from home and left to die in fear.”

Thus, at the very end of his life, Yeats created an image that seemed the very opposite of what had nourished his imagination most. His heroic figure has now been gentled; his fierce and solitary warrior has joined others in the act of sewing; instead of the company of brave men, Cuchulain seems content to rest finally among cowards. This poem, then, is not a culminating statement for Yeats but a contradictory one; it is not a crowning version of a familiar poetic form but an experiment in a form associated most with Dante. Instead of attempting to sum up, it is as though Yeats wished to release fresh energy by repudiating, by beginning again, by offering his hero a set of images alien to him that served all the more to give the hero ambiguity, felt life, unsettlement.

In this way, late work becomes itself unsettling. And in the late work of other writers this example of an imagination refusing to lie down and sum up can be seen. It would be easy to imagine, for example, that Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice was written toward the end of his life. In fact, it was written in 1911, when Mann was thirty-six. It is a young man’s book; its images of desire, decay, and death could not be so easily entertained by a writer facing into late or last work.

Advertisement

Mann’s last work, in fact, was a comedy, a book filled with trickery and amusing, almost throwaway parodies. It was begun when Mann was in his mid-thirties and continued when he was seventy-five and prone to illness, around the time when he would return from America to live in Switzerland. The book is titled Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man. In its use of a heavy style to convey light material, in its episodic structure, in the sheer roguishness of Felix Krull, the novel represents a rueful commentary on its author’s own past seriousness, as well as a way of proposing a fresh start for him, narrated by a trickster. But more important, perhaps, is the fact that Mann completed volume one with the suggestion that subsequent volumes would follow. The picaresque story that Felix told of his exploits was open-ended. It left room for Mann to continue as though there would be no end. Its very lightness set about defying death, even if Mann died a year after the book’s publication.

“Every piece of work,” Mann wrote, “is a realization, fragmentary but complete in itself, of our individuality.” Perhaps the writer whose individuality seems to intensify the most, becoming in his late work both more mysterious and more apparent, is Bacon’s close contemporary Samuel Beckett. Beckett’s work in the 1980s—he died in 1989 at the age of eighty-three—pares down form and language to a minimum in both fiction and drama.

Two of Beckett’s very last works throw interesting light on the work of Bacon, especially the late paintings. Both are concerned with the figure or the self as protean, uncertain, unsingular, ready to be doubled or shadowed, poised to move outward into a second self, or another self, or into a figure hovering near, waiting for substance.

In Nacht und Träume, for example, written for German television in 1982, a figure known simply as A dreams a second figure, B, into being. Two hands then appear as part of the dream. There are no words, merely snatches of the Schubert lied “Nacht und Träume.” The dream fades when A awakens, only for the sequence to repeat itself more slowly as the music is heard once again. The short play is not concerned with death so much as with the fluidity of the self, or the way in which night and dream and indeed ghostly music allow the self to move into another realm, a shadow realm, or a realm made possible by the imagination itself in which another figure waits.

Nacht und Träume is Beckett’s penultimate play. In prose, the very last piece he wrote was Stirrings Still, conceived toward the end of 1984 and completed three years later. This short text starts with the same idea as Nacht und Träume. It questions the autonomy, the singleness of the self. It begins: “One night as he sat at his table head on hands he saw himself rise and go.” The opening of the second paragraph repeats this with a minor variation. The figure is not, however, moving toward death, but toward another place in life. He will disappear only to reappear. The piece ends with: “Time and grief and self so-called. Oh all to end.” The very core of the process of fiction—the idea of self—is questioned here and undermined. This is fundamental to the drama that Beckett created as last work.

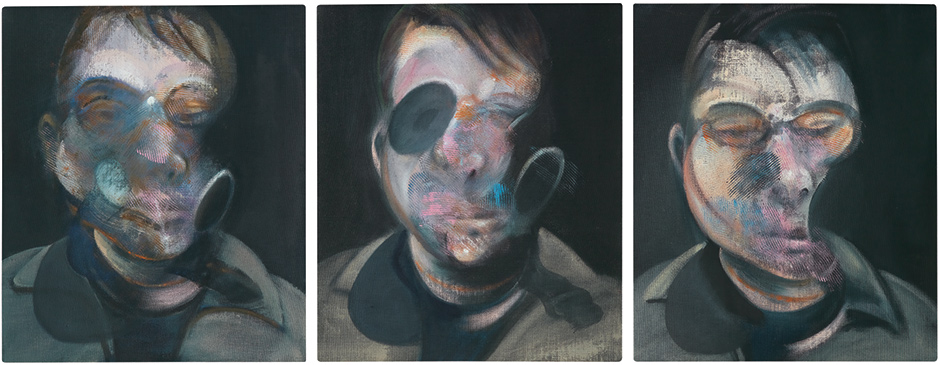

In this context, it is useful to look at Bacon’s grave triptych Three Studies for Self-Portrait (1976), with its three faces fluid against a black background. As the eye moves from left to right, the face in the first section appears like a mask. It is fully visible in the center panel, gazing outward. In the right-hand section, the face is already in another realm, some of it having merged with the blackness. What little of it remains has an aura of enormous suffering. It is not nothing, just as Beckett’s “Oh all to end” emphasizes the fact of utterance within a continuity rather than an actual end. Nothing has ended. Instead of nothing, there is “all,” or the irony surrounding all.

As with Beckett’s Nacht und Träume or Stirrings Still, it would be too crude to suggest that Three Studies for Self-Portrait is a way of prefiguring death. In late work, no artist is concerned directly with death but rather with creating new form—often jagged, disturbing form, and often form that plays stillness against some deep and energetic stirring within the self, as though to emphasize that art is made only by the living.

Advertisement

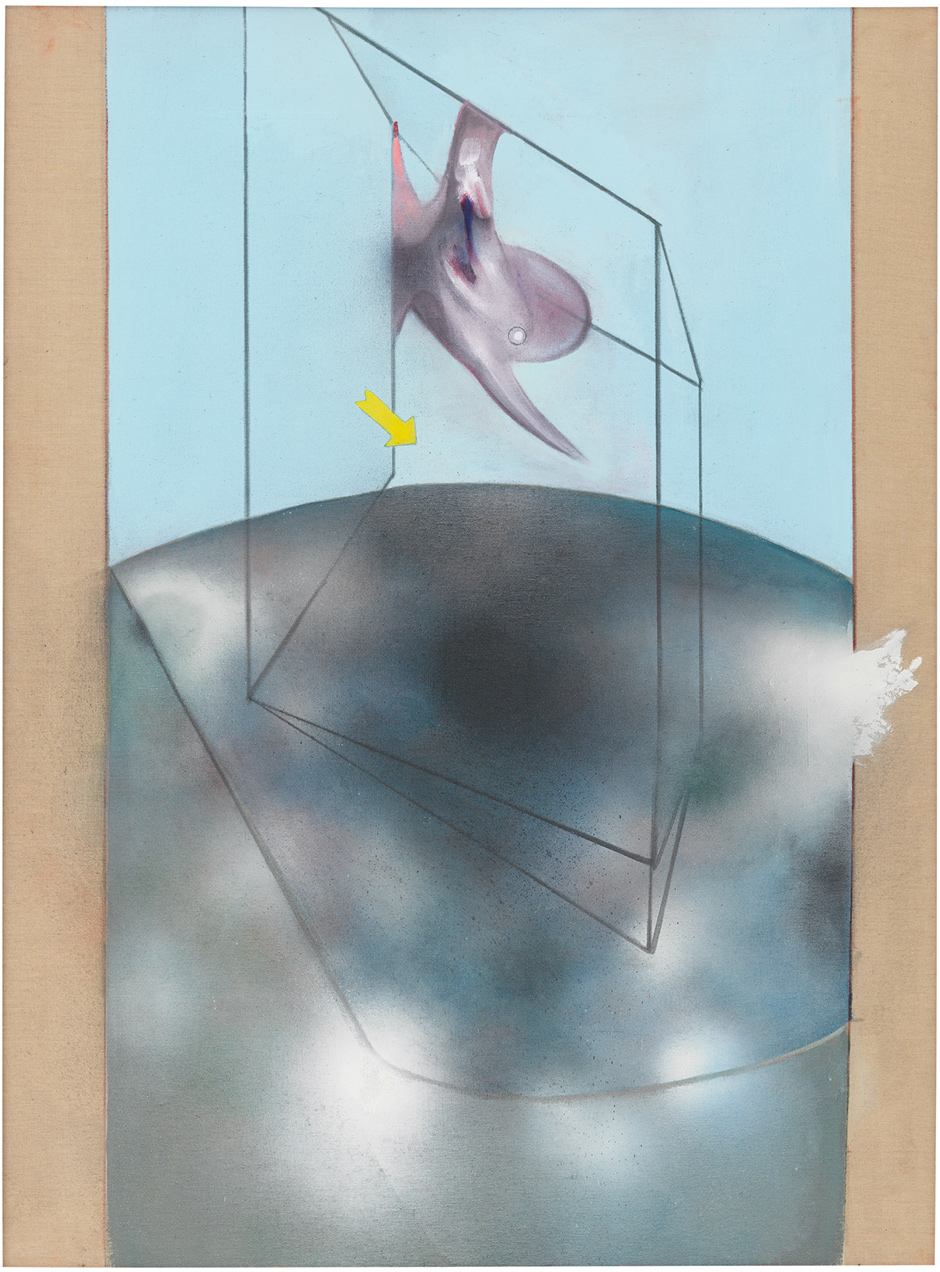

In Beckett’s Nacht und Träume, then, the self lives with its dream-self, its shadow-self. In some of Bacon’s other late work, the figure, filled with painterly substance, is shadowed by another shape, a shape that has elements of the human form. In Still Life: Broken Statue and Shadow (1984), for example, it is interesting to see Bacon confronting the same problem faced by Beckett when dealing with the human presence, the human figure. In some of his late work, Beckett could not see the figure as single or self-contained, or simply moving toward death; instead he saw it as being able to extend beyond its own boundaries, finding what Joseph Conrad called a “secret sharer,” even if the secret sharer was just the next sentence.

Bacon in this painting makes the shadow figure more ghostly, stronger in outline than in positive space or texture. It is not a shadow of the statue itself, having a different shape, which suggests that it has its own leftover presence. It is, oddly, substance as well as shadow.

Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, The Lambrecht Schadeberg Collection/© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved./DACS, London/ARS, NY 2015. Photography by Christian Wickler. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

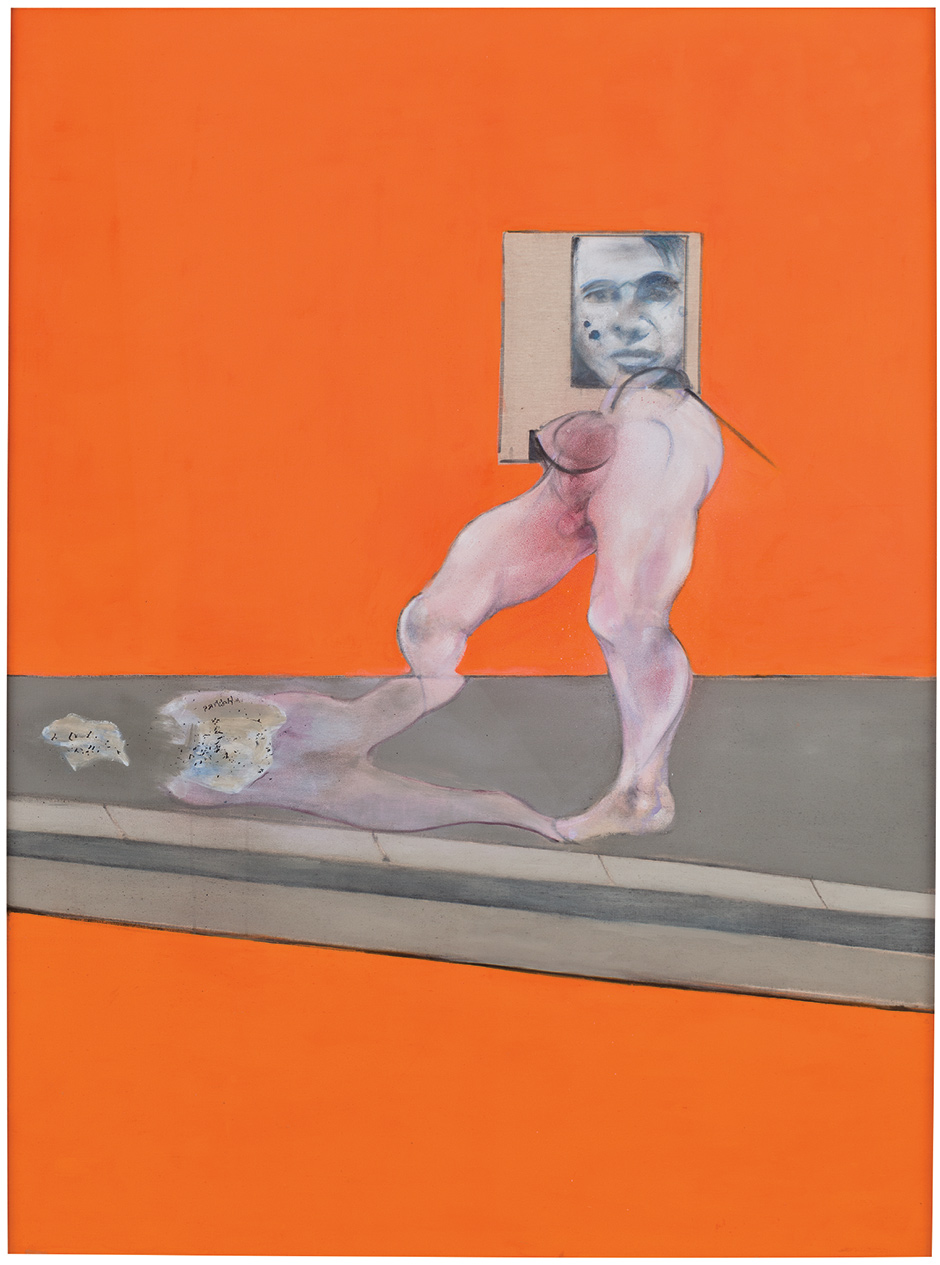

Francis Bacon: Study from the Human Body and Portrait, 1988; oil on canvas, 78 x 58 1/8 inches

This happens, too, in a number of other late works by Bacon, such as Study from the Human Body and Portrait (1988), in which the face is filled with substance only to give way to the fleshy torso and legs that have less solid presence. And they in turn give way to their own shadow. This happens again in Figure in Movement (1978), as the writhing, suffering sexual figure, filled with energy and life, has a shadow almost like something the police might chalk on the pavement at the scene of a crime to mark the outline where a body had been.

In both Beckett’s and Bacon’s work, this idea of the figure as fluid rather than, say, single or inert has its origins in necessity as much as in philosophy. There is a sense in the late work of both artists that they are too busy seeing and working with form to be bothered thinking about or burdening us with philosophy. There is something deeply exciting and dramatic about a second self, a figure waiting for the transfer of energy that will allow it to come to life, however flickeringly. Beckett was a dramatist even at his most minimal. He wished to create excitement even at his most restrained. And so he made such doubles. Bacon made clear in interviews how much the very imperatives of image-making mattered to him.

Thus these shadows, this blurring of self, at its most intense and magisterial—for example, in Bacon’s Self-Portrait of 1987—created a force and energy in the pictures that would strike the nervous system of the viewer more powerfully than any single, stable figure.

It is important to remember that playing with the ghostly or the shadowy, using them to create pictorial mystery and excitement, makes its way through Bacon’s entire body of work, just as the idea of a double or an alternate self will appear in earlier Beckett plays such as Krapp’s Last Tape, written in 1958. So, too, does Yeats use the same sort of clear, chiseled statements of “Cuchulain Comforted” in poems as early as “Adam’s Curse,” published in 1904. And Mann was interested in parody and trickery throughout his life.

Therefore when we think about late work we need to bear in mind connections as much as distinctions, continuities as much as departures. Nonetheless, if we look at Bacon’s Sand Dune (1983), Painting March 1985 (1985), and Blood on Pavement (1988), all three filled with mysterious shapes, layers, and presences, hovering toward and then resisting abstraction, set in a sort of aftermath, a place where the body has been, it is possible to feel that Bacon was not content merely to find images that would deepen what he had already done, or would distill his vision, or would totalize it. Instead, there is a restlessness here that we also find in Beethoven’s late chamber music—a feeling that Bacon might begin again, that he is searching for some way to make images that he knows will only be possible for artists of the future, if they are even possible at all.

Working is a way, in any case, of keeping such knowledge at bay at least for the time being, a way of confronting the material world, of outfacing it, as though time might actually relent or the spirit might gain more substance than anyone has ever before imagined.