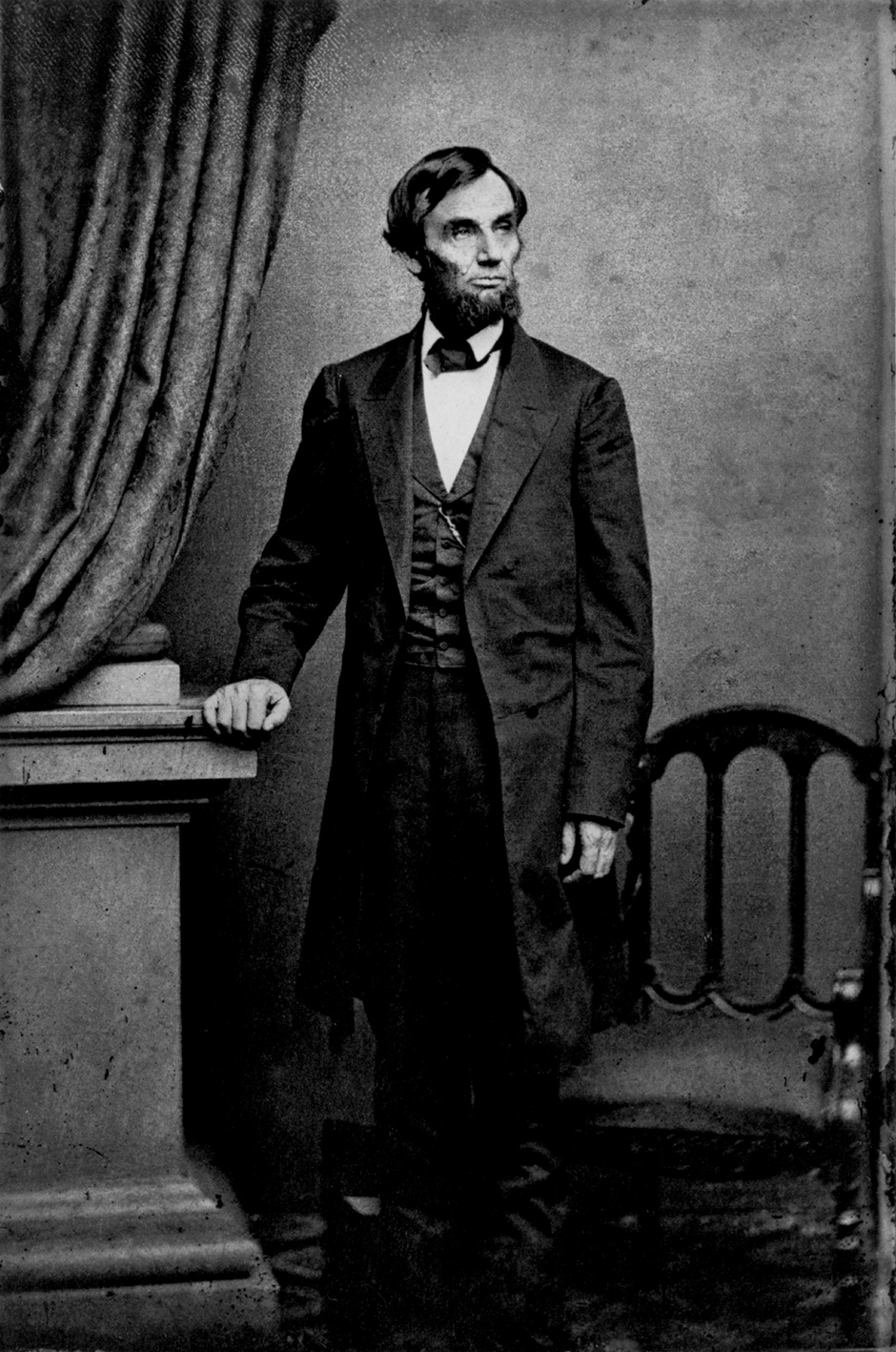

By early April 1865, the Confederacy was in free fall. William Tecumseh Sherman had cut a swath of destruction through Georgia and the Carolinas. On April 2, Ulysses S. Grant broke Robert E. Lee’s line at Petersburg, Virginia. The next day Grant took Richmond, the Confederate capital. Abraham Lincoln arrived there on April 4 and was greeted by jubilant crowds of emancipated blacks.

Meanwhile, Jefferson Davis, the gaunt, austere president of the Confederacy, had joined the evacuation of Richmond and had fled to Danville, Virginia. But he had not lost faith in his cause. Davis issued a proclamation to the Southern people that stated confidently, “Nothing is now needed to render our triumph certain, but the exhibition of our own unquenchable resolve. Let us but will it, and we are free.”

It was a desperate rallying call by a leader who would not accept defeat. Five days after Davis made it, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House. But Davis continued to cherish the Confederacy’s ideals. Fifteen years after the war ended, he wrote that “African servitude” in the South had been “the mildest and most humane of all institutions to which the name ‘slavery’ has ever been applied.”1

Such ideas are so mistaken that it might seem that Davis should be dismissed as deluded. James McPherson invites us to adopt a more nuanced view in Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief. McPherson calls the Southern cause “tragically wrong” but adds, “I have sought to transcend my convictions and to understand Jefferson Davis as a product of his time and circumstances.” Davis emerges in McPherson’s portrait as a hands-on military leader who, despite several painful chronic illnesses, kept close watch on his generals, devised battle plans, and sometimes risked his life by visiting the front lines.

With his background as a West Point graduate and a successful colonel in the Mexican War, Davis at the start of the Civil War was far more deeply versed in military matters than his rival, Lincoln, who had no combat experience and who had to learn about war strategy on the go. That the North won the war had little to do with ineptitude on Davis’s part. His choice of such generals as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson made good sense, as did his “offensive-defensive” strategy, which involved concentrating his troops and attacking the enemy at key moments—a strategy that, as McPherson explains, Davis was forced to abandon through much of the war in favor of a more dispersed, defensive position. The North’s superior troop numbers, industrial strength, and firepower did not guarantee the South’s defeat. Outmanned and outgunned forces can sometimes stand up to stronger powers, as shown by the American Revolution or the Vietnam War.

But one wonders how Davis could have kept up his spirits for so long. McPherson shows that he faced disagreement, spite, and insolence among several of his generals. As the Confederacy’s battlefield losses mounted, he was blasted by rival politicians like Senator Louis Wigfall, who called him “an amalgam of malice and mediocrity,” and newspapers like the Richmond Examiner, whose editor declared that “every misfortune of the country is palpably and confessedly due to the interference of Mr. Davis.” Yet Davis remained determined. He made some mistakes, but in the end, it was Grant’s unrelenting attacks on Confederate armies along with Sherman’s destruction of infrastructure, especially water systems, industry, and civilian property, that brought the South to its knees. McPherson concludes that “the salient truth about the American Civil War is not that the Confederacy lost but that the Union won.”

Embattled Rebel is one more piece of the magnificent Civil War jigsaw puzzle that McPherson has been assembling for five decades. Other pieces are the twelve essays, eleven of which have previously appeared in various venues and formats, contained in his latest book, The War That Forged a Nation: Why the Civil War Still Matters. A distillation of many themes that McPherson has long pursued, The War That Forged a Nation, which contains autobiographical passages amid ruminations about history, leads us to consider his career as a historian and public intellectual.

Descended from two officers who fought for the North (but not, apparently, from the famous Union general James Birdseye McPherson), James M. McPherson was born in North Dakota, raised in Minnesota, and educated at Gustavus Adolphus College. He had little interest in the Civil War until he studied it as a graduate student under C. Vann Woodward at Johns Hopkins. Just as Woodward’s book The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955) was a catalyst of the civil rights movement, so McPherson developed an interest in Civil War radicals that reflected the Sixties’ spirit of social protest. In his words, “parallels between the 1960s and 1860s, and the roots of events of exactly a century earlier, propelled me to become a historian of the Civil War and Reconstruction.”

Advertisement

His doctoral dissertation on abolitionism led to the publication of his early books, The Struggle for Equality: Abolitionists and the Negro in the Civil War and Reconstruction (1964), The Negro’s Civil War: How American Negroes Felt and Acted During the War for the Union (1965), and The Abolitionist Legacy: From Reconstruction to the NAACP (1975). Woodward, as general editor of the multivolume Oxford History of the United States, invited McPherson to contribute to the series a book on the Civil War. McPherson, meanwhile, had bought a secondhand Olympia typewriter (it “was state of the art as of about 1970,” he later joked) on which he would write many of his books, including the widely used textbook Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (1982).

For Woodward’s Oxford series, McPherson expanded the scope of his inquiry. The result was Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), which told the history of the war and its backgrounds in a moving narrative. His originality lay in his deft synthesis of many aspects of the war—military, political, social, diplomatic, and economic—in a single book (a previous ambitious synthesis, Allan Nevins’s Ordeal of the Union (1947–1971), consisted of eight volumes). While wide-ranging, Battle Cry of Freedom was neither unfocused nor meandering; it put the struggle over interpretations of slavery and freedom at the very heart of the war—a needed corrective to Civil War historians who had sidelined slavery in favor of other themes. McPherson also stripped the war of spurious romanticism by portraying it as a tragic failure of American politics, a war that caused more American deaths, proportional to population, than all other wars combined.

To the surprise of McPherson and his publisher, the nine-hundred-page book became a runaway best seller. The hardcover edition spent sixteen weeks on the New York Times best-seller list, and the paperback version was on the list for another twelve weeks. Upward of three quarters of a million copies of Battle Cry of Freedom sold worldwide. Even now, some 15,000 copies sell each year. The book received rave reviews and won the Pulitzer Prize.

Success, however, brought new challenges for McPherson. He earned a chair professorship at Princeton, but there were signs of an academic backlash. A colleague warned McPherson of the risk of becoming a “popular historian” instead of a “historian’s historian.” McPherson received a letter from a University of Michigan Ph.D. candidate who asked, “Have you had occasion to feel that your public success has diminished your achievements in the eyes of fellow professionals?” McPherson wrote a piece on “Historians and Their Audiences,” in which he posed the question, “What’s the matter with history?” He noted the chasm between academic and popular historians. He might just as well have asked, “What’s the matter with academe?” Every academic field has specialists who write for fellow specialists—what Eric Hayot calls twenty people writing for each other—while holding suspect scholars who have a wide appeal.

McPherson identified three main audiences for Civil War history: professional historians, who are especially interested in political and socioeconomic aspects of the war; Civil War buffs, who mainly enjoy reading about battles; and “general readers” or “the lay public” of the sort reached by Bruce Catton or Shelby Foote. McPherson is the rare case of someone who has managed to reach all three audiences. His sales have been strong, and despite occasional nitpicking by academics, the reviews of his books in scholarly journals have been largely favorable. His scholarship is at once rock-solid and accessible. He delivers prodigious research in clear prose.

Popular interest in the Civil War, which had been particularly high in the 1960s, subsequently waned until the appearance of McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, which was soon followed by Ken Burns’s 1990 PBS documentary series The Civil War, which attracted more than 40 million viewers. Then came a plethora of books, articles, films, museum exhibits, battle reenactments, and discussion groups that kept the Civil War surge going. McPherson himself has contributed to the surge on many levels. He has continued to write monographs on war-related topics, including the motivation of Civil War soldiers (What They Fought For, 1861–1865 and For Cause and Comrades), the Union and Confederate navies (War on the Waters), and Lincoln (Tried by War and Abraham Lincoln). He has produced essay collections—including This Mighty Scourge, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, and now The War That Forged a Nation—as well as a Civil War atlas, histories of individual battles, a collection of Civil War letters, and history books for elementary and junior high schools. A lot of fine writing has come from the clattering keys of that old Olympia.

Advertisement

McPherson’s influence on our understanding of the Civil War becomes especially visible when we compare him to historians of the 1930s and 1940s. Known as revisionists, these historians regarded the Civil War as needless or “repressible.” In this view, the war was provoked by fanatical abolitionists and power-hungry Republicans whose denunciations of slavery stirred up the North and provoked the South to secede from the Union. The bloodbath that followed might have been avoided had tempers cooled and had slavery been allowed to die out on its own as a result of changing economic realities. Reconstruction, from this vantage point, was a brief period of nightmarish race-reversal in which blacks behaved in ways that threatened whites. Such attitudes were allegedly encouraged by nefarious Radical Republicans and followed by a justified reaction by Southern whites who reasserted their political and social dominance over African-Americans.

This interpretation of the Civil War was in time sharply attacked by a number of historians, including Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and John Hope Franklin, but it was McPherson who most forcefully presented a very different picture of the war, one that is now widely accepted as standard. In his view, the Civil War was a moral struggle over slavery between two sections of the country that were driven by conflicting ideologies. The war represented the inevitable collision of opposing interpretations of liberty and revolution. In the North, liberty and revolution signified resistance to the Southern “slave power,” which had controlled politics and defined America for much of the seven decades after the American Revolution. For the South, liberty meant the independence of the states, in which owning slaves was entirely legitimate and revolution meant a forceful rejection of a strong federal government that violated states’ rights.

The two sides were led by presidents who embodied these opposing attitudes: Lincoln, who navigated among competing Northern groups while holding together the Union and working to emancipate America’s four million enslaved blacks; and Davis, who endured internecine squabbling, a collapsing economy, and battlefield setbacks to keep alive the dream of a Confederate slaveocracy. Both presidents, McPherson argues, were, overall, sound military strategists who tested out several less-than-stellar generals before arriving at dependable ones.

McPherson emphasizes the role of contingency. There were times when a chance occurrence turned the tide of the war. Take the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg, to Southerners) in Maryland on September 17, 1862. The war’s bloodiest battle, it was a military draw. But by stymieing Lee’s invasion of the North, it boosted Union morale, led to Lincoln’s issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and may have prevented England’s intervention on behalf of the South. This crucial battle was influenced by a Union corporal’s accidental discovery of three cigars wrapped in what turned out to be Robert E. Lee marching orders—an unexpected windfall for General George McClellan, who wired Lincoln, “I have the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap.”2

As late as August 1864, the outcome of the war was so uncertain that Lincoln confided to his Cabinet that he would probably lose his bid for reelection in November. The subsequent aggressiveness of the Union army and navy, under Lincoln’s guidance, led to his reelection and the North’s triumph.

That triumph redefined America. As McPherson maintains, the “Union” of individual states was now an indivisible “nation.” He argues that the war supplanted the old southern-defined vision of America with what he describes as the northern politico-economic system and the social values it generated.

Another outcome of the war was the notable strengthening of the federal government. Before the war, McPherson notes, the only federal agency that affected the average citizen was the postal service. Under Lincoln, the United States created a national currency, powerful federal courts, and the first federal income tax. Liberty itself took on new meanings. Between the 1789 and 1861, so-called negative liberty—freedom from something—permeated the national consciousness and shaped the first ten constitutional amendments, with their “shall nots.” The Civil War brought about a shift to positive liberty, or freedom to. This shift was reflected in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, which gave freedom and citizenship to millions of African-Americans in declarative phrases like “Congress shall have the power to enforce….” Positive liberty, McPherson notes, can open the way to justice, social welfare, and equality of opportunity.

McPherson’s arguments about the Civil War may seem to be so plausible as to be unassailable. But he has faced questions on issues such as the violence of war, the actions of African-Americans and Lincoln, and the motivations behind the conflict.

On the question of violence, as he describes it in The War That Forged a Nation, McPherson stakes a middle ground between those who lament the war’s allegedly gratuitous brutality and those who insist that the war was actually restrained. In answer to a historian who claims that Lincoln’s “taste for blood” resulted in “unmitigated violence, slaughter, and civilian suffering,” McPherson reasons that the aim of destroying slavery in fact necessitated what General Sherman called “the hard hand of war.” Also, the roughly 50,000 civilian deaths that resulted directly or indirectly from the war amounted to about one fifteenth of soldier deaths, a relatively small proportion when compared with the collateral damage in large-scale European wars from the seventeenth century onward, in which twice to several times as many civilians died as soldiers.

To refute the opposite notion—that the violence of the Civil War was in fact moderate—McPherson again uses comparative statistics. Even if we go with the old figure of 620,000 Civil War deaths (recently raised to an estimated 750,000), the 360,000 Union dead represented 1.6 percent of the population of the Union states, while the 260,000 Confederate dead constituted 2.9 percent of the Confederate population (including slaves). Proportionally, as he points out, such a death total today would be the equivalent of a staggering 8.8 million.

In his own books, McPherson does not frequently resort to what the historian John Keegan called the “Zap-Blatt-Banzai-Gott im Himmel-Bayonet in the Guts” approach to military history, with accounts of spilled intestines, spouting blood, brains blown out, and so on. While McPherson’s emphasis on strategy and troop movements sometimes makes a battle seem more like a chess game than a slugfest, he has proven fully capable over the years of communicating the horrors of war in powerful, if understated, ways.

McPherson attributes the war’s violence to a widely felt, passionate commitment to principle. Soldiers on both sides fought with genuine devotion to their respective causes. Here McPherson departs from previous historians like Bell Irvin Wiley, who maintained that both the rebels and the Yanks were spurred mainly by economics or community pressure, and Gerald Linderman, who contended that the grim realities of war stripped most soldiers of idealism. Having read thousands of soldiers’ letters and diaries, McPherson finds that Southerners generally fought for duty and honor while Northerners were also impelled by duty and, increasingly, by a resolve to eradicate slavery.

Getting rid of slavery was naturally a strong motivation among the roughly 180,000 African-American soldiers who fought for the Union. But this raises another issue. A number of historians maintain that American blacks were principally responsible for bringing about emancipation, not only because of the exemplary courage of black soldiers but also because of the thousands of enslaved people who took the initiative to escape from their masters and flee to the Union army, where they were liberated.

McPherson, who pioneered the study of African-Americans in the war, fully appreciates their contribution. But in The War That Forged a Nation he finds the self-emancipation thesis inadequate. He points out that had the Union armies not pushed progressively southward, enslaved people would have had no convenient destination to escape to. For McPherson, emancipation was the result of a combination of factors—the military aggressiveness of Lincoln and his generals, the rising antislavery sentiment in the North, and the commitment of many freedom-seeking Americans, black and white.

Lincoln does not go unscathed in McPherson’s rendering. A military tyro at the start of the war, he misjudged a number of generals and condoned some wrongheaded battle schemes. But meditating on Lincoln over the years has led McPherson to adopt an increasingly positive view of him. Lincoln’s choice of generals early on in part reflected his attempt to mobilize various constituencies for the war effort by appointing prominent political and ethnic leaders, such as the Tammany Democrat Daniel Sickles, the Irish-born Thomas Meagher, and the German-American politician Carl Schurz. Even George McClellan, whose exaggerated estimates of the size of rebel armies limited his battlefield effectiveness, was an initially understandable choice, given his skills at preparing troops and his great popularity among soldiers. With regard to battle strategy, Lincoln, after some initial stumbling, came to espouse the effective one of potent assaults on Confederate forces combined with the destruction of Southern infrastructure and resources.

In response to those who, citing occasional racist pronouncements by Lincoln, argue that the president was a thoroughgoing bigot, McPherson shows that his racism was more apparent than real. In order to get elected and then hold together the many competing factions in the North, Lincoln tailored his public declarations on race and slavery carefully so as not to appear extreme. At the same time, he did not show hostility toward African-Americans when he met with them privately, as was testified by two prominent visitors to the White House, Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, who found a unique absence of racism in him.

“All subjects are infinite,” Herman Melville wrote when he was at work on Moby-Dick. “The trillionth part has not yet been said; and all that has been said, but multiplies the avenues to what remains to be said.” Melville, were he around today, would surely concede that more than a trillionth part has been said about the Civil War. But one can envisage new kinds of Civil War history that explore many aspects of culture that McPherson does not consider. For instance, he rightly states that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) “may have done more to arouse antislavery sentiments in the North and to provoke angry rebuttals in the South than any other event of the antebellum era—certainly more than any other literary event.”3 He does not discuss much other war-related fiction or the numerous poems, plays, songs, reform tracts, and other cultural material that, were they integrated into a full history of the war, would enhance our understanding of it. But McPherson, through his energetic research, unflagging curiosity, and extraordinary breadth of scope, has opened the way for such work.

Walt Whitman declared that the ground for his poetry volume Leaves of Grass was well “ploughed and manured” by others. The Civil War ground has been expertly prepared by many remarkable historians—none more remarkable than James McPherson.

-

1

See Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (D. Appleton & Co., 1881), Vol. 1, p. 78. ↩

-

2

See McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam (Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 107–109. ↩

-

3

See McPherson, Drawn with the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War (Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 24. ↩