I am one of a team that has been redesigning the Greek and Roman Galleries in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. We’ve finished—and a couple of weeks ago the new display opened to the public. This is nothing on the scale of the new Greek and Roman galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, of course. But, after the British Museum and the Ashmolean in Oxford (also recently “re-hung”), the Fitz has the best collection of classical antiquities in the UK—thanks to generous donations since the mid-nineteenth century from professors and alumni of the University.

Our task was, partly, to bring it up to date in museological terms. So we have used a lot of label and panel space in discussing not only the ancient history of the objects, but also what has happened to them since—who found them, who bought or collected them, who restored or conserved them, and how? My own favorite story is the “Parthenon metope” brought back to Cambridge from Athens by Edward Daniel Clarke, who went on to become the professor of mineralogy. He bought it from the Turkish garrison commander at about the same time as Lord Elgin’s men were removing their “marbles.” And Clarke was very smug that his own piece of the famous temple had been acquired completely legitimately. The only problem, as you can now read in the gallery, is that it was not a piece of the Parthenon at all, but a piece of Roman sculpture probably from a nearby theater. Smugness is always dangerous in archaeology.

One big dilemma was how to welcome visitors to the galleries: what object should greet them as they entered? This was made more difficult to decide as two different routes converged on our entrance, and we did not want to privilege one above the other. We decided to show a colossal head of Antinous, found in the eighteenth century at Hadrian’s Villa a Tivoli. Raised on a pedestal above eye level, and set at an angle, he manages to greet visitors entering by both doors.

Antinous has a colorful history. He was the young Bithynian “favorite,” and presumably lover, of the emperor Hadrian, who drowned in mysterious circumstances in the river Nile in AD 130. “Did he jump, was he pushed or did he merely fall?” are questions that have never been resolved. Marguerite Yourcenar’s idea in her Memoirs of Hadrian that it was more than simple suicide, but a religious self-sacrifice, is one of many appealing, extravagant, and untestable theories. Hadrian, in any case, is said to have been grief stricken: he turned the boy into a god and littered the Roman world with his statues—of which this is one.

It was only at the opening party that I began to wonder how we were going to sell Antinous to the hundreds of seven-year-olds who visit these galleries (seven being the age that the British National Curriculum decided that schoolchildren should study Greek art). How were we intending to make Antinous and his story meaningful for them—without prompting a stream of complaints from outraged parents?

A few days later I realized that a new book by Christopher P Jones, New Heroes in Antiquity, possibly held an answer. Modern heroism—as in “hero worship,” “culture hero,” “working class hero,” and so on—is not quite the same as the ancient version. The heroes that Jones discusses were divine or semi-divine figures, occupying part of that large grey area between “proper” Olympian gods and poor suffering, ordinary humanity. For the Greeks and Romans, “hero-worship” was not a metaphor. The grave of a hero would become a religious shrine (in Greek, heroon) and receive sacrifices and offerings from those who came, literally, to worship.

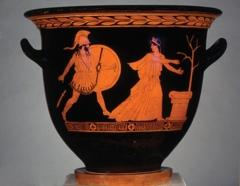

It is impossible to pin down exactly what the qualifications were for ancient heroic status. Like many ancient religious categories it was capacious and its boundaries conveniently vague (as a general rule, Greco-Roman polytheism tended to incorporate rather than exclude). For a start, anyone who fought in the Trojan War was a “hero”—for the ancient Greeks saw this as the great former age when all “mortals” were “heroes.” Some were even given their own shrines. Visitors to Sparta in the fifth century BCE would have been able to visit the Menelaion—an impressive sanctuary of King Menelaos and his errant wife Helen (also a “hero” on this definition—and worshipped in Sparta well into the Roman period, and probably for longer than Menelaos himself). There are some tremendous ancient images of this kind of hero in a stunning new exhibition, Heroes: Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece, organized by the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, currently on show at the Frist Center in Nashville.

But Jones is more concerned with heroes who were created from the classical period of Greece on. He starts from the Spartan general Brasidas who died fighting the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War and was worshipped as a “hero” in the city where he had fallen, with sacrifices and annual games. He shows that it was probably “heroization” that Cicero had in mind when, four centuries later, he planned a “shrine” (Latin fanum), to be erected for his dead daughter, Tullia. And his last main example from pagan antiquity is Antinous—whose cult, as established by Hadrian, he sees very much in ancient “heroic” terms.

Advertisement

It’s an excellent book. But I found myself most interested in how it would help me in my own particular dilemmas with the seven-year-olds. We can skate over the details of the relationship between Hadrian and Antinous, and we can wonder about different versions of heroism—from the Homeric “heroes” on view on the Athenian vases through Antinous, to their own view of who might count as a hero.

Christopher P. Jones, New Heroes in Antiquity: From Achilles to Antinoos (Harvard University Press, 2010)

Heroes: Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece is on view until April 25, 2010 at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee.