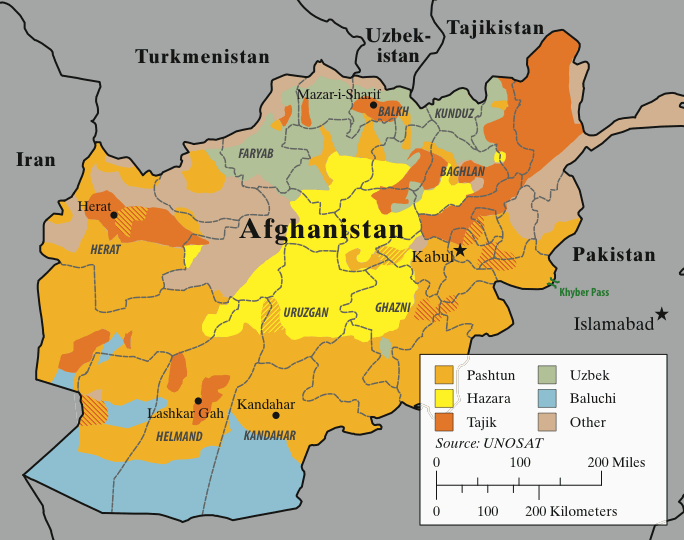

Here is a map of Afghanistan. Versions of it adorn conference rooms in military bases, ministry buildings and NGO headquarters. The first question it raises is: “Why does Afghanistan exist?” The country contains about a dozen ethnic groups, whose distribution is shown here in simplified form. There is no coast to attract people and trade. One should also bear in mind Afghanistan’s tribal divisions, particularly within the Pashtun ethnic group, which is split into numerous clans and smaller descent groups. These are too complex for a cartographer to suggest.

Then there are the affinities that the various groups feel to one or other of the country’s neighbors. Concentrated in the south and east, the Pashtuns have an attachment to their fellow Pashtuns in Pakistan. The Uzbeks and Turkmens are adjuncts to bigger communities beyond the northern border, while the Baluches, down in the south-east, maintain ties with their (again, more numerous) kinsmen in Pakistan and Iran. The Tajiks, by contrast, are more local in their loyalties. These affinities scorn the country’s frontiers as they were drawn by British and Russian officials around the turn of the 20th century, when Afghanistan was a buffer between the Tsar’s dominions and British India. Pashtun tribesmen don’t recognize the Durand Line dividing Afghanistan and Pakistan. Nor do the Taliban and the US, fighting their mobile war. Baluch drug smugglers cross into Pakistan and Iran at will.

Afghanistan’s Persian-speaking majority is culturally attuned to Persian-speaking Iran and Tajikistan, to which may be added the sectarian affiliation that the country’s Shia minority (mostly Hazaras, concentrated in the central, most mountainous part of our map) feel towards Shia Iran.

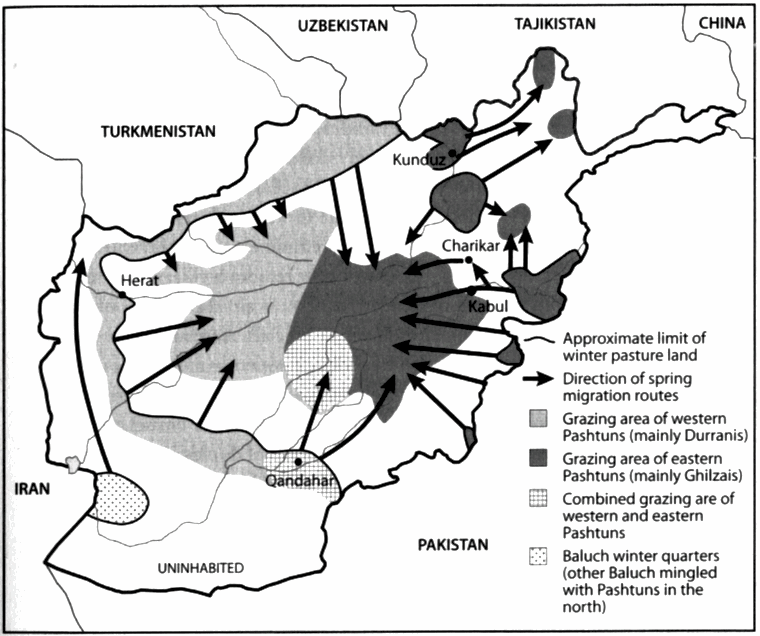

The centrifugal forces hinted at in this ethnic cartography seem to militate against Afghanistan’s survival, but maps can be misleading if they are not accompanied by other information. Afghanistan survived a savage civil war in the 1990s without coming apart. Today, the country’s strongest political movement is the Taliban, which has partially reinvented itself as a nationalist movement—clearly, the idea of Afghanistan resonates strongly with many people. Older impulses also favour unity. A highly revealing map in Thomas Barfield’s new book, Afghanistan: a Cultural and Political History, shows that every spring up to a million nomadic shepherds, from many disparate Afghan tribes, drive their flocks hundreds of miles from the border areas towards the well-watered highlands of the Hindu Kush that bestride the center of the country.

If, as seems likely, President Obama’s Afghanistan strategy comes unstuck over the coming months, more voices are likely to be raised in favour of partition. This is what Robert D. Blackwill, a deputy national security adviser during the presidency of George W. Bush, proposed this summer, and he repeated his message when he addressed the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London on September 13. Blackwill’s idea is that an unruly south may be quarantined from the north, where, as he observes, “locals are largely sympathetic to US efforts,” and that a deal needs to be made with the Taliban “in which neither side seeks to enlarge its territory.”

Among other pitfalls, Blackwill anticipates “pockets” of “fifth column” Pashtuns in the north and west. In fact, as our map shows, Pashtuns are found in quite big swathes outside their southern heartland; to relocate them would require ethnic cleansing. Blackwill also assumes that resistance to the US is confined to Pashtuns, when all the evidence suggests that anti-Americanism is now widespread among all ethnic groups. The effect of partition would not be to isolate the most unstable parts of the country, but to unite Afghans of different backgrounds around the goal of re-unification.

The Obama administration persists with its own plan, which is to beat the Taliban using increased numbers of troops and then hand the country over to the Afghan authorities. The administration wants to do this as quickly as possible, but a precipitate US withdrawal would lead to an intense civil war, with the Afghan National Army likely to dissolve under ethnic pressures. (It is currently dominated by the Pashtuns and the Tajiks.) The prize would be Kabul, but such a war would be driven less by advancing armies than by strife between existing communities, for the capital is as cantonized as the country as a whole, and its communities have access to a huge quantity of arms.

That, of course, would need another map.