Joan Sutherland, the Australian-born prima donna assoluta, was nearly the last survivor among the top sopranos of the twentieth century. Yet Sutherland, who died on October 10 at the age of 83 at her home in Switzerland, is now not so highly regarded in some quarters as her foremost contemporaries, even though in purely technical terms she outstripped almost all of them.

Her voice was as big as Leontyne Price’s and nearly as big as Birgit Nilsson’s; she could spin out haunting pianissimo effects akin to Renata Tebaldi’s fabled morbidezza; and her trill was not only better than Beverly Sills’s, but the best in the business since Luisa Tetrazzini, who retired when Sutherland was a child. And for clockwork consistency, she could sing rings around the incomparable but erratic Maria Callas.

Sutherland’s reputation has languished because of her apparent desire to preserve her vocal resources at all costs. From the early 1970s onward—her stage career spanned four decades until her retirement in 1990—she gravitated toward roles that flattered her voice but were dramatically unchallenging, not to say inane, including such late-nineteenth-century French piffle as Delibes’s Lakmé and Massenet’s Esclarmonde.

In that respect Sutherland was the antithesis of Callas, her pioneering forerunner in the great postwar revival of the early-nineteenth-century Italian Bel Canto tradition. Callas burned herself out vocally within a matter of years by throwing all caution to the winds and singing with searing intensity and utter abandon in rediscovered works by Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini.

Sutherland played the handmaiden Clotilde to Callas’s high priestess in Bellini’s Norma at Covent Garden in 1952, when the star offered some prescient advice she might well have followed herself. “Now look after your voice,” Callas, who was just three years her senior, told Sutherland, “We’re going to hear great things of you.”

A decade later, when Sutherland finally took on Norma’s fearsomely difficult title role, she attained a Platonic vocal ideal in that part equaled by no soprano before or since. The demonic Callas and the plucky Sills were infinitely superior actresses—Sutherland was at her inadvertent best playing the wind-up doll Olympia in Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann—though neither was endowed with anything like her formidable vocal support.

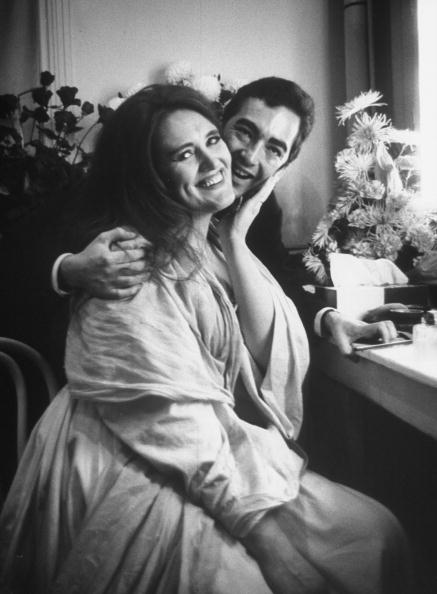

Once her stardom was established, Sutherland insisted on being conducted by her husband and fellow Australian, Richard Bonynge. They met in London, where Sutherland moved from Sydney with her mother in 1951 to study at the Royal College of Music. Signed by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden a year later, she created a sensation in 1958 with an electrifying “Let the Bright Seraphim” in Handel’s Samson. The following season she triumphed in Lucia, and her renown skyrocketed.

A self-taught musical historian, Bonynge was of inestimable help in prodding Sutherland into the Bel Canto parts that fit her instrument to perfection. His recessive orchestral style was geared to framing singers, especially his wife, but his interpretations remained wholly devoid of the intellectual depth and visceral power evinced by Georg Solti and Herbert von Karajan.

Critics somewhat unfairly disparaged Bonynge as a lightweight, even a hanger-on, as did Rudolf Bing, the Metropolitan Opera general manager who gave Sutherland her 1961 debut there in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (a tumultuous success that won her a rave in The New York Times and a spot on The Ed Sullivan Show, the period’s twin seals of mainstream cultural approval). As the bitchy Bing wrote of the couple in his caustic but entertaining memoir, 5000 Nights at the Opera (1972), “I accept the old Viennese saying that if you want the meat, you have to take the bones,” and behind Bonynge’s back referred to him as “Mr. Bones.”

Even before her Met debut, Sutherland produced one of the shrewdest self-marketing tools in operatic history: her tour-de-force two-disc compilation The Art of The Prima Donna (1960). Among the first must-have classical recordings of the hi-fi LP era, Sutherland’s astounding diva demo was arranged in more-or-less chronological order, from the flinty English Baroque of “The Soldier Tir’d” from Artaxerxes by Thomas Arne (composer of “Rule, Britannia!”) and her show-stopping “Seraphim”; on through Bel Canto gems by Bellini and Rossini (including a ravishingly definitive “O rendetemi la speme” from the former’s I Puritani); then culminating with Verdi and the French Romantics.

In addition to Sutherland’s phenomenal top notes—high F was easily within her range— the double album flaunted a prodigious versatility that promised a stage repertoire of uncommon breadth. In 1965 I saw her debut Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust with the Philadelphia Lyric Opera Company, and her incandescent “Jewel Song”—happily preserved on The Art of the Prima Donna—was nothing short of breathtaking, and outsparkled the paste bijoux she dandled.

Advertisement

But Sutherland never lived up to those expectations. Bonynge’s unending search for lesser-known vehicles that would cosset Sutherland’s vocal chords led to many exercises in pointless antiquarianism. Her diction was atrocious—perhaps because she characteristically pulled her lips over her teeth— and some found it difficult to discern even what language she was singing in.

With a remarkable lack of self-awareness, La Stupenda (as Sutherland’s Italian fans dubbed her; Callas was La Divina) considered her greatest achievement to be the title role in Esclarmonde, an exceedingly silly medieval fantasy that the Met revived at her behest in 1976, after a well-deserved hiatus of sixty-four years. In the climactic scene, the heroine reveals her identity by parting a heavy veil. Sutherland, who was what used to be termed “big-boned” and no beauty, caused titters as her prominent chin jutted forth from her disguise, and the overbaked music reached a schmaltzy crescendo.

Occasionally, though, she would rouse herself and turn in an excitingly involved performance, as she did in the title role of Puccini’s Turandot, a 1972 recording led by Zubin Mehta. She could also be a game comedienne, as I fondly remember from her 1972 Met romp in the title role of Donizetti’s La fille du régiment, opposite Luciano Pavarotti before he abandoned himself to terminal bleating. Sutherland gaily mugged and larked about like some jolly-hockey-sticks at St. Trinian’s (the fictional English girl’s school created by the cartoonist Ronald Searle).

If Sutherland’s generally tepid stage deportment left much to be desired, her still-thrilling recordings do not. Thus it seems likely that her recording legacy will ensure a place in the annals of opera as exalted as that of her great Australian predecessor and idol, Nellie Melba. La Stupendissima now only lacks a dessert named after her, too.