Since 1992, the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude—known for such works as Wrapped Reichstag (1995) and The Gates in Central Park (2005)—have been pursuing Over the River, their plan to suspend great swathes of luminescent fabric over a 42-mile section of the Arkansas River in Salida, Colorado for a period of two weeks. (Jeanne-Claude, Christo’s collaborator for more than forty years, died in November 2009.) The project has provoked heated debate among Salida residents about its potential environmental and economic effects. The federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which oversees use of public land, is expected to rule on the project early next year. In anticipation of its decision, the BLM recently published a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Over the River and invited public comments. The following statement was submitted by the art historian Leo Steinberg.

Jubilation is the dominant mood when- and wherever a Christo/Jeanne-Claude project is realized. I have witnessed it time and again—32 years ago, in Loose Park, Kansas City, overlooking its Wrapped Walk Ways, every inch of the winding itinerary paved with bright clinquant stuff, of which Christo remarked: “When the sunlight falls on that nylon and sets it sparkling, it’s very beautiful.” He saw no need to boast about cheerful families bestriding the luster under their feet as if walking on air.

Joy hailed the Surrounded Islands in Biscayne Bay, Miami, May 1983: eleven small isles, each in its private hug, embraced by the scandalous pink of buoyant industrial fabric.

Or, more recently in Central Park, Manhattan (2005): abundance of Gates, waving their saffron scarves, 7,503 of them, erected to host processions of walkers, whose glee reminded ambulant seniors of the smiles that lit up this same city on V-E Day, 1945—except that the present fête needed no losing side.

For half a century now, I have wondered what it is in the actuality of a Christo/Jeanne-Claude project that generates such civic felicity. Let me try again.

A realized Christo extravaganza, seen to be of no conceivable use, is instantly recognized as a fantasy, a thought whose unlooked-for concretion offers respite from purpose. We are invited to sojourn inside a meditation, to dwell in peace and companionship with coincident opposites, within mutually contradictory terms.

Remember what the Christos in 1995 inflicted on the Berlin Reichstag, hot-seat of Germany’s first fragile parliamentary democracy. Did Christo’s symbolism wrap it up for easy travel, to signal removability, send it packing, as we say? Was it wrapped to protect it in situ, or even in tenderness, seeing that no one in living memory had given the building such hands-on care? The effect was irreducibly paradoxical. A familiar metropolitan landmark the size of a city block had been converted to secrecy, packaged like a gift waiting to be unwrapped; the modesty of the wrapping perhaps meant to mock the pretensions of the object inside.

On the other hand, this muffled object now loomed more massive and taller than the Reichstag’s own architecture ever allowed. The thing humbled had been somehow augmented, empowered. Anybody could see that its present vesture would soon be sloughed—as if to ease the Reichstag to a new birth. A simplicity of visual thinking to brood on and recollect, never to disentangle.

When a Christo project sets out to engage a body of water, as in Surrounded Islands, some prognosticators inevitably foresee an assault upon peaceable, innocent nature. The work completed reveals, on the contrary, acts of homage secured in reverence and affection.

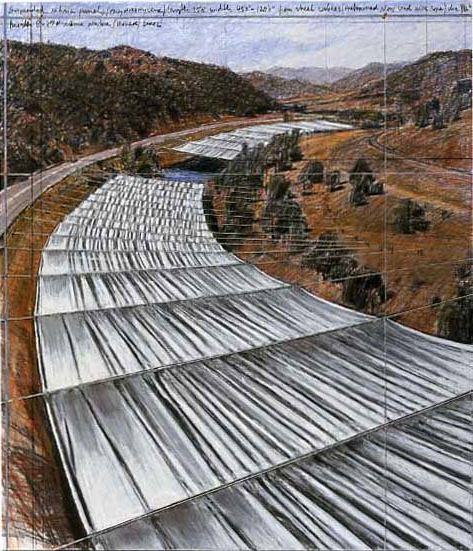

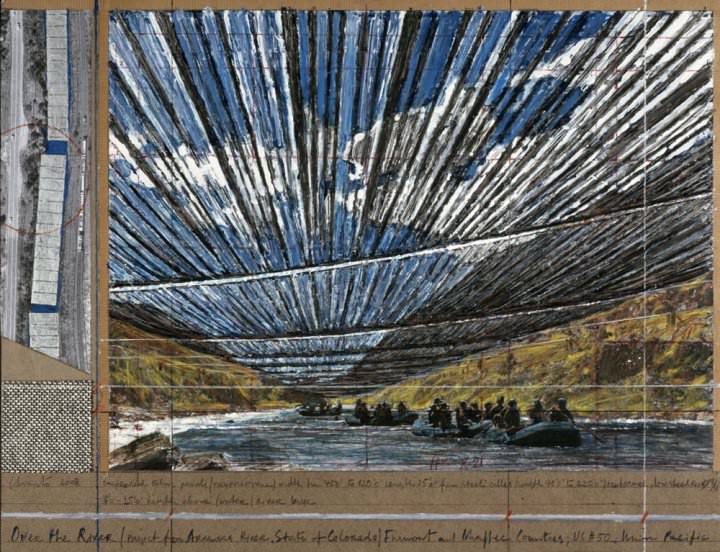

And so Over the River, Christo/Jeanne-Claude’s still fought-over bid to canopy portions of the Arkansas River in Colorado. Once again, we hear the project denounced as an imposition that would deny the river and its dependents access to quickening sunshine and rain; as if the instigators were out to crush whatever under the sun grows, flows, or draws breath. But many among us foresee the river’s planned canopy delivering a benign gesture.

From Christo’s explanations and explicit drawings of what is envisioned, I anticipate certain surprises, among them a welcome revision of the river’s deportment in three-dimensional space. A river tends to be seen and thought of along the horizontality of its stream—a level course which Christo’s parallel canopy seems to confirm. But that canopy—pitched only 8 feet above the water’s surface—is to be of a transparent cloth that keeps sky and cloud always in evidence, and with it (I hope) a sharpened awareness of living under pillars of air. To say nothing of the river’s own depth in unceasing play. In other words, I expect Over the River—more precisely the low thatch overhead—to impart a livelier sense of the river’s participation in verticality.

Advertisement

The word “thatch,” just used, confesses another association. That of roofing for protection from, say, “inclement” weather. Not that a river needs such solicitude; what threatens it is the insidious infusion of industrial waste. But Over the River is not out to indict a pollutant. Its metaphorical idiom is content to assert the immanence of a champion, a protective agent just now engaged in benediction.

Let me recall the epiphany in Francis Thompson’s poem “The Hound of Heaven,” where the soul, after long flight from its pursuer, wonders at last:

Is my gloom, after all,

Shade of His hand, outstretched caressingly?

I would sustain the analogy only this far: that the artists who conceived a thatch for the Arkansas, or for exemplary portions of it, are friends to the river.