On December 10, I attended the award ceremony in Oslo, Norway, for the Nobel Peace Prize, which the government of China had a few days earlier declared to be a “farce.” The recipient was a friend of mine, the Chinese scholar and essayist Liu Xiaobo, whom Oslo was now referring to as a Laureate and Beijing as a “criminal” serving an eleven-year sentence for “incitement to subvert state power.”

Countries that have embassies in Oslo were invited to send representatives to the ceremony, but the Chinese government had aggressively called for a boycott. In the end, forty-five countries attended, but another nineteen—including Russia, Pakistan, Cuba, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Vietnam—chose to stay away. How much their decisions were motivated by sympathy for the Chinese government’s position and how much by pressure from China over matters of trade and diplomacy is impossible to measure. From the United States, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi attended, along with Representatives David Wu of Oregon and Christopher Smith of New Jersey.

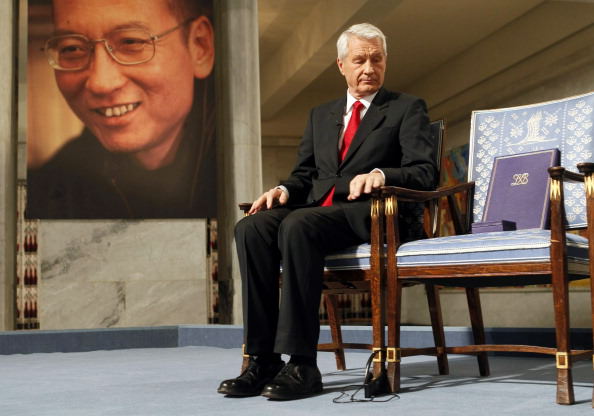

The ceremony was one of the most exquisite and moving public events I have ever witnessed. The presentation speech was made by Thorbjørn Jagland, the chairman of the prize committee who is a former prime minister of Norway and now secretary-general of the Council of Europe. Only a few minutes into the speech, he said:

We regret that the Laureate is not present here today. He is in isolation in a prison in northeast China…. This fact alone shows that the award was necessary and appropriate.

When he had finished reading these words the audience of about a thousand people interrupted with applause. The applause continued for about thirty seconds and then, when it seemed that the time had come for it to recede, it suddenly took on a second life. It continued on and on, and then turned into a standing ovation, lasting three or four minutes. Jagland’s face seemed to show an expression of relief. After the ceremony, in a news interview, he said that he understood the prolonged applause not only as powerful support for Liu Xiaobo but as an endorsement of the controversial decision that his five-person committee had made.

In the remainder of his speech Jagland stressed the close connections among human rights, democracy, and peace. He reviewed the other four occasions in Nobel history when a Peace Laureate was prevented from traveling to Oslo: in 1935, the Nazis held Carl von Ossietzky in prison; in 1975 Andrei Sakharov was not allowed to leave the USSR; in 1983, Lech Walesa feared he would be barred from reentering Poland if he went to Oslo; and in 1991, Aung Sang Suu Kyi was under house arrest in Burma. Even so, each of the latter three laureates was able to send a family member to collect the prize. Only Ossietzky and now Liu Xiaobo were prevented from sending a family member.

Jagland stressed that his committee had great respect for the Chinese nation, and observed that support of dissidents makes countries stronger, not weaker. The US had become a stronger nation because of the work of Martin Luther King, Jr., another Nobel Peace laureate.

After Jagland’s speech the Norwegian actress Liv Ullman read the full text of the statement that Liu Xiaobo had prepared for his trial in Beijing in December 2009. The statement is called “I Have No Enemies,” and it was significant that Liv Ullman read it in full because, at Liu’s 2009 trial, his own reading had been cut off after fourteen minutes. The presiding judge that day had interrupted him, declaring that the defendant would not be allowed to use more time than the prosecutor, who had summed up Liu’s crimes in only fourteen minutes. Ullman’s reading took about 25 minutes and was beautiful. She held the audience in immaculate silence when she read a passage in which Liu Xiaobo pays tribute to his wife Liu Xia:

I am serving my sentence in a tangible prison, while you wait in the intangible prison of the heart…. but my love is solid and sharp, capable of piercing through any obstacle. Even if I were crushed into powder, I would still use my ashes to embrace you.

The reading was followed by songs from a Norwegian children’s choir. Liu Xiaobo’s wife, Liu Xia, was able to see Liu Xiaobo in prison on October 10, before she was placed under house arrest, and he told her his wish that children participate in the ceremony.

The climactic moment of the ceremony came when Jagland, unable to hand the Nobel diploma and medal to Liu Xiaobo, placed both upon the empty chair where Liu was supposed to have been sitting.

Advertisement

None of Liu Xiaobo’s friends living inside China, whom he had wanted to invite to Oslo, were able to witness these poignant moments (although some have been able to see it on the Web, nothwithstanding Chinese censorship). Attending in person, however, were about three dozen veterans of China’s human rights struggles who are now living in exile. Su Xiaokang—the writer of River Elegy, a television series that suggested that Communist Party rule is based in China’s “feudal” traditions and that had a tremendous impact in China in the summer of 1988—saluted Norway. “The big democracies—America, Britain, France, Germany—all know what democracy is but won’t stand up in public to Beijing’s contempt for human rights. It takes a little country to do a big thing.” Renée Xia, overseas director of China Human Rights Defenders, commented that her friend Liu Xiaobo’s empty chair, while regrettable, was in part a good thing. “To us,” she said, “that empty chair is not the least bit surprising. Of course Beijing treats its critics that way. This is wholly normal. If the rest of the world is startled, then good; maybe surprise can be the first step to better understanding of how things really are.”

Fang Lizhi, the pro-democracy astrophysicist who spent thirteen months in refuge inside the US Embassy in Beijing after the Tiananmen Massacre of 1989, overheard Renée Xia’s comment and added, with his characteristic puckish wit, that in a sense China’s rulers should feel satisfaction that they finally have aroused the attention of the Nobel Committee. “All those earlier atrocities—during the Anti-Rightist Movement, the Great Leap famine, the Cultural Revolution, the Beijing Massacre—weren’t enough to get a Nobel Prize for a Chinese person. But now the world is starting to care what happens in China. It’s a sign that China is now a ‘big country’, and that’s what Beijing has always said it wants, right?”

But many of the Chinese supporters of Liu still felt that well-intentioned Westerners have a long way to go before they really understand China’s politics. The Norwegian hosts repeatedly expressed a hope, for example, that Liu Xiaobo will soon be allowed to come to Oslo to collect his prize. Exiled Chinese who heard this kind-hearted wish knew, but did not say, how unrealistic it was. Even if Liu Xiaobo were to be released from prison, it is unimaginable that he would agree to leave China. If he left, the regime could bar him from re-entry, as it has so many others, and his ability to influence life and ideas inside China would decline precipitously. Liu Xiaobo is smart enough not to let such a thing happen, so as long as the medal remains in Oslo, it is likely he will be separated from it for a long time. (His wife—who has been under effective house arrest and unable to communicate with anyone since a few days after the award was announced in early October—could in the future try to collect it, but she, too, would have to calculate the risk of forced exile.)

Liu knows that the greatest potential for his ideas, and the most important effects of his Nobel Prize, will unfold inside China. China’s rulers have consistently denounced his Charter 08 as “un-Chinese,” even while they assiduously prevent its publication inside China, apparently from a fear that ordinary people, were they to read it, might not find it so un-Chinese. The Internet is porous, and the Nobel Prize will certainly make Chinese people curious to learn more about Liu Xiaobo.

In the twenty-four hours following the announcement of the prize on October 8, the Chinese-language website at Human Rights Watch, which was featuring Liu Xiaobo, got more hits from mainland China than it had gotten in total for about a year. Jimmy Lai, a refugee from Mao’s China who is now a media mogul in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and who flew to Oslo to support Liu Xiaobo, borrowed Mao’s famous line from 1949 that “the Chinese people have stood up.” They didn’t really stand up then, said Lai. “But now it could happen. Now people can see that ‘China’ in the twenty-first century can be something much bigger and better than the Communist Party.”

While others shared this kind of optimism, for many a lining of fear persisted as well: it is just too hard to say which side will win. At a happy gathering in the mid-afternoon of December 9, for example, Renée Xia received an urgent phone call from Beijing. Zhang Zuhua, who had been Liu Xiaobo’s main collaborator on Charter 08, had just been abducted by plainclothes police on a Beijing sidewalk. This was only hours before the Nobel ceremony was to happen. Zhang was brought in a car that had curtains on the windows to a Public Security guesthouse near Beijing, where he was allowed to read but was held in a room that had no electric light, so when the sun went down reading stopped. His room was part of a suite, and he was allowed to go out into the sitting area with the police to watch television and chat. He was also allowed to stroll in the courtyard with the policemen. Zhang was held until December 12, and then was allowed to go home. It may have been that the authorities wanted to eliminate any possibility of a telephone hook-up to Oslo. In any case they gave no reasons. But when this happened to Liu Xiaobo two years earlier, the eventual sentence was eleven years. One never knows what will happen.

Advertisement

Hu Ping, editor of Beijing Spring in New York and a long-time personal friend of Liu Xiaobo’s, held little hope that China’s rulers would ever soften their position toward democracy and human rights. “As they see it,” Hu said,

the current strategy works. The formula “money + violence” works, and we stay on top. We know what the world means by human rights and democracy, but why should we do that? Aren’t we getting stronger and richer all the time? Twenty years ago the West wasn’t afraid of us, and now they have to be. Why should we change what works?

Hu recalled something that Liu Xiaobo had said to him many years ago. “We are lucky,” Hu reported Liu as saying, “to live in this time and this place—China. It may be difficult for us, but at least we do have a chance to make a very, very large difference. Most people in their lifetimes are not offered this kind of opportunity.”