At dusk on the afternoon before Thanksgiving Day in 2002, my family and I returned to our home in Chilmark on the island of Martha’s Vineyard to discover fifty-six cows on our newly sown lawn. We turned the car around and drove to our neighbor’s house. She called the cow herder, who arrived banging the dinner pail. The cows stampeded to their field next door.

The stone wall I share with my neighbor, a good friend, serves as a boundary between us. It had begun to fall, and where a thicket of brambles obscured the collapse, the cows found a place to cross.

I wanted to rebuild the wall. At first, my neighbor suggested repairing the electrical fencing on her side, but I was concerned that it might fail again. There were a few tense days while we decided what to do. During those days, I walked the wall on my side. It was the first time I had really looked at it intently. Who had built this wall and when? It was beautiful. Stones rested on each other, securely or tentatively, many covered with lichen. Branches cast their shadows.

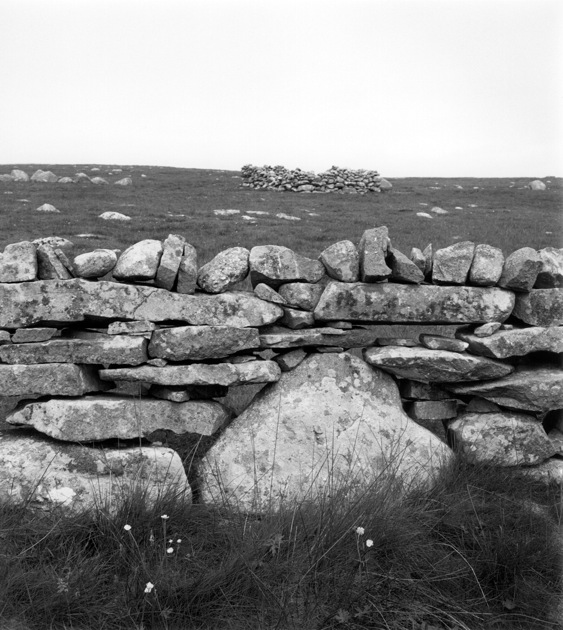

I photographed the wall. I made images of it in all seasons, of both the bits that were still upright and of the tumbled rocks, too. The appearance of each captivated me. I wondered about dry stone walls elsewhere. Over the next eight years, I traveled to places, quite arbitrarily, to see for myself: New England, Kentucky, Britain, Ireland, the Mediterranean, and Peru. Land itself does not know national or political bounds. Across these different regions, the deforested landscapes had been carved by human beings. In stony places everywhere, farmers built walls to contain their animals, remove stones from their arable fields, and define property.

As I traveled from one stony place to another, I discovered a similar story shared by disparate peoples. Farmers everywhere must work diligently to maintain their walls in landscapes ravaged constantly by the elements. The sad fate of family farms is the same everywhere. Unlike their parents before them, many farmers today know their land may not go to the next generation. Often children have no desire to stay. The walls are replaced by concrete blocks, wire, or wooden fences. Properties are sold. Second growth forests hide the fallen stones that once shaped farms. The self-sufficient family life and closeness bred by the farm is disappearing with its walls.

I had always thought of stones as being hard, heavy, and immovable. Indeed they can be, but I came to understand how vulnerable and fragile they are too. Sometimes there’s a crack running through a rock and the rock will break over time. Often, lichen grows on them. Rocks will fall from a wall when vines or tree roots grow through them. Untended, the walls tumble down.

Click on any of the images below to open the slide show.

Wall in Sky. White Peak, England, 10 March 2004. Sixteenth century medieval wall of the pre-enclosure period.

Limestone Field with Puddle. Inis Meáin, Ireland, 5 July 2005. When the English invaded Ireland, they settled on the more arable land in the east and forced the Irish west where the soil was poor or non-existent. By mixing sand and seaweed, the Irish made rich soil and placed it on the limestone plateaus. Where fields are no longer farmed, the soil has washed away, and only the plateaus and delineating farm walls remain.

Black Crag Field. Inis Meáin, Ireland, 4 July 2005. Seventeenth-century wall built on top of a thirteenth-century sheep creep.

Uphill Wall with Ferns. North Stonington, Connecticut, 20 September 2008.

Bearna, Inis Meáin, Ireland, 4 September 2005. There is no wood on the Aran Islands with which to make a gate. Farmers block passageways with piles of stones which they must remove and replace each time they go in or out of their fields.

Feed Passthrough, Inis Meáin, Ireland, 17 September 2005. The passthrough enables feeding animals in two fields simultaneously.

Knobs, Hatun Rumiyoq, Cusco, Peru, 31 December 2004. These protrusions were carved to drag and position the fifty-ton stones. Curiously, every year at noon on the summer solstice, each protrusion casts a diagonal shadow which ends precisely at the adjacent stone’s corner.

Hagar Qim Temple, Malta, 12 May 2006. This is among the most ancient religious sites. It is the oldest dry stone structure on earth, built between 3600 and 3200 B.C. It is older even than Stonehenge.

Delsetter Erratic, Shetland Islands, 3 July 2007. The large triangular-shaped stone is not indigenous to the area but was carried there by a glacier during the ice age.

Broken Wall, Houndkirk, Dark Peak, England, 16 May 2005.

Poison Ivy on Wall with Step Stile, Bourbon County, Kentucky, 4 November 2009. The protruding flat rock serves as a step for pedestrian traffic to cross the wall.

Advertisement

Stone Walls: Personal Boundaries, a book of photographs by Mariana Cook from which this slide show is drawn, has just been published by Damiani Press.