The ever growing recognition of mid-twentieth-century architectural photography has elevated the reputations of Julius Shulman, Ezra Stoller, and Balthazar Korab from that of workaday chroniclers of America’s postwar building boom to co-inventors of the High Modernist mystique. The strongly composed images of these three photographers—typified by such classics as Shulman’s crepuscular poolside view of Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House in Palm Springs, Stoller’s penetrating exploration of Eero Saarinen’s nautilus-like TWA Terminal at JFK airport, and Korab’s soaring evocations of Saarinen’s aerodynamic Dulles Airport near Washington, DC—have come to define a veritable school of photography. United in the emphasis on high-contrast clarity, bold graphic impact, and linear dynamism, these photographs were often superior to the buildings they glamorized.

Yet there is a fourth member of their generation whose remarkable work on modernism has been far less widely known: Pedro E. Guerrero, who will turn 95 later this year, and who for many years was Frank Lloyd Wright’s favorite lensman. He got the gist of the architect’s communal work ethic right off the bat, with an initial series of photos that depicted Taliesin Fellowship interns slaving away on desert construction sites like WPA-mural workers brought to life. And this Arizona-born photographer’s ability to mitigate the blinding daylight of Taliesin West, the architect’s winter base of operations in Scottsdale from 1937 onward, remains unparalleled.

It is particularly welcome then, that the Julius Shulman Institute at the Woodbury School of Architecture in Burbank has organized Pedro E. Guerrero: Photographs of Modern Life, the first major retrospective of his work, which traces his career from the late 1930s through the 1960s. Guerrero began his association with Wright in 1939, when he joined the Taliesin Fellowship in Scottsdale, Arizona as an apprentice. The first Chicano to enroll there, he could not afford the school’s high tuition—$1,100—but Wright waived the fee in return for the young man’s photographic services. Their warm, almost father-son relationship continued until the master’s death two decades later.

We can see why America’s greatest architect favored Guerrero, for no other photographer has better understood how Wright integrated his buildings into their natural settings. But the architect’s sustained patronage was not enough to support Guerrero and his growing family, and after serving in the army during World War II he turned to commercial photography in New York City and moved to New Canaan, Connecticut—then the epicenter of Modernist residential design—though he always remained on call to shoot his mentor’s latest creations.

Working for the period’s most stylish glossy magazines, Guerrero devised a deceptively suave manner that in retrospect can seem quite subversive. Two of his slyest images during those years address the rise of America’s car culture, which went into overdrive during the Eisenhower administration and the development of the interstate highway system.

Guerrero’s black-and-white Diamond Gas Station (1961) shows a 1959 Chevrolet Impala pulled up to a pump in Macon, Georgia. The car sits under a snazzy canopy of three concrete “mushroom” columns with conjoined flaring tops that clearly derive from the supports Wright devised for the Great Workroom of his Johnson Wax headquarters of 1936-1939 in Racine, Wisconsin. But in this flamboyant filling-station adaptation by the little-remembered Georgia architect Thomas Little, Wright’s ingenious structural solution has become a mere styling device, a point Guerrero drolly emphasizes by juxtaposing the shelter with the identically curved bat-wing taillights of the Chevy parked beneath it.

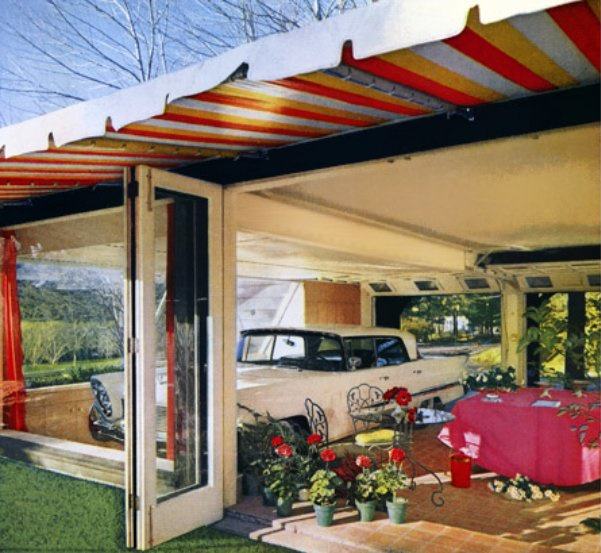

A more mordant commentary on the intrusion of the automobile into every aspect of American life during the postwar era—which witnessed such dubious innovations as the first drive-in church, converted from an outdoor movie theater in Orange County, California in 1955—is Guerrero’s The Living Garage (1959). Commissioned by Condé Nast’s House & Garden, where Guerrero was a regular contributor, this color tableau depicts an unnamed interior in New Canaan that, like Philip Johnson’s nearby Glass House of 1949-1951, blurs distinctions between indoors and outdoors with transparent window-walls overlooking a verdant landscape.

But whereas the most remarkable artifact in the open-plan living-dining area of Johnson’s weekend retreat is one of three known versions of Nicolas Poussin’s The Burial of Phocion (1648), the outstanding feature in the living room Guerrero portrays is a huge white 1958 Lincoln Premiere (not coincidentally Wright’s favorite make of American automobile, though his 1940 Lincoln Continental was Cherokee red, the architect’s hallmark color). The message this incongruous domestic arrangement clearly conveys is that if you love your car so much, why don’t you just move in with it?

If Guerrero’s pictures often lack the riveting assurance of Shulman’s, Stoller’s, or Korab’s slam-dunk imagery, they can also surpass his contemporaries’ typically glib endorsements of the work they depicted. Guerrero’s ability to be more critical, albeit often in ways far less obvious than his competitors’ energetic triumphalism, gives his sometimes deceptively quiet art an aspect that repays extended contemplation.

Advertisement

In his affecting autobiography, Pedro E. Guerrero: A Photographer’s Journey with Frank Lloyd Wright, Alexander Calder, and Louise Nevelson (2007), the photographer tells of the magnanimity with which Wright, whose pacifism curdled into isolationism in the run-up to World War II, accepted his apprentice’s decision to leave Taliesin and enlist after Pearl Harbor. Decades later, Guerrero’s very different attitude toward the Vietnam War brought an abrupt end to his lucrative two-decade stint at Condé Nast.

When Guerrero, who served on New Canaan’s branch of the Selective Service System, was labeled in a 1968 New York Times article as “the dove on the draft board,” he was deemed too politically risky by Condé Nast’s Machiavellian editorial director, Alexander Liberman (for whom I worked in the 1980s). Assignments there suddenly ceased, and no reason was ever given. Though Guerrero received repeated anonymous telephone threats because of his unwavering antiwar stance, he bravely refused to resign from the draft board until it was disbanded in 1974.

Resigned to the compromising realities of commercial magazine work, Guerrero from his sixties onward turned to the documentation of the two artists he most admired after Wright: Alexander Calder and Louise Nevelson, whose workplaces he exhaustively photographed, the basis for superlative monographs that make Liberman’s glossy coffee-table book The Artist in His Studio (1960) look rather chichi.

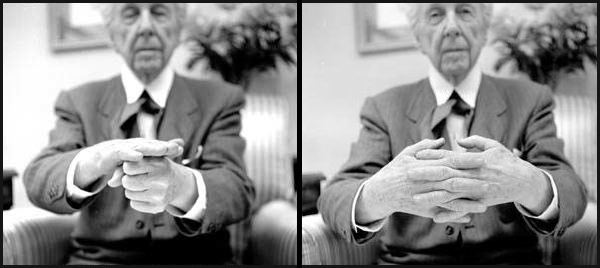

I first met Guerrero that same year, as I edited a collection of Wright’s “In the Cause of Architecture” articles for the book division of Architectural Record magazine. That sixteen-part series had appeared in its pages between 1908 and 1928, the lowest stretch of the architect’s roller coaster career. In the course of that project I became enthralled with Guerrero’s 1953 photographic sequence of Wright demonstrating the difference between conventional construction techniques and his own organic architecture.

These twelve black-and-white close-ups of Wright’s hands capture an eloquent contrast between the age-old post-and-lintel tradition—shown by his fingers and fist touching at right angles—and Wright’s new conception of the building art as expressed through fingers expressively interwoven. In soft focus behind those hands we see the benign visage of the resilient octogenarian, who with such simple gestures could evoke his epoch-making Prairie Houses and the heartland terrain from which they arose.

Pedro E. Guerrero: Photographs of Modern Life an exhibition organized by the Julius Shulman Institute at Woodbury University, is on view through April 25 at WUHO, the Woodbury University Hollywood Gallery.