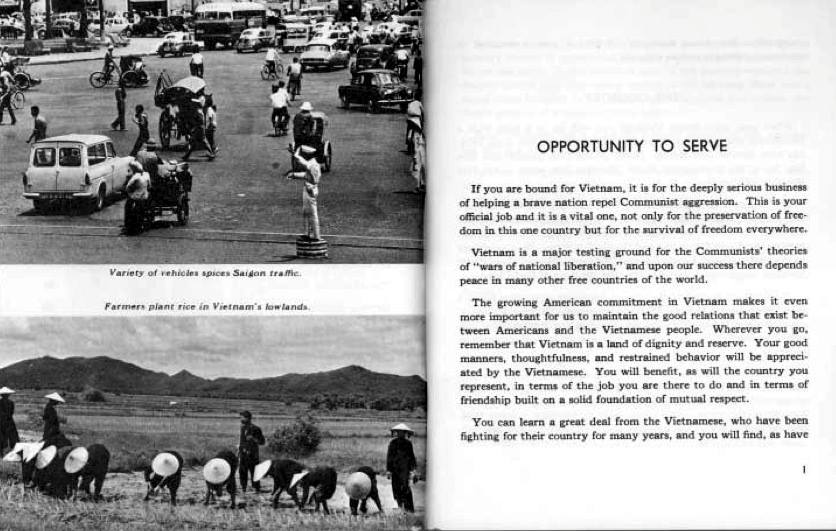

Most American soldiers landing in Vietnam in the 1960s were handed a ninety-three-page booklet called A Pocket Guide to Vietnam. Produced by the Department of Defense, it described how small, well-proportioned, dignified, and restrained Vietnamese people are, how the delicately-boned local women appear in their flowing national dress, how Vietnamese love tea, and don’t like slaps on the back, how they excel at cooking fish. Peasants labor in their paddies and at their traditional crafts, while upper-class men never work with their hands.

We are “special guests here,” the guide says, and should be courteous at all times, treat women politely, and make friends with their counterparts in the Vietnamese army. (The Americans must have been relieved to be told they were not subject to Vietnamese law, an arrangement, according to the guide, that “has worked out very well.”) At the end of the booklet are a few Vietnamese phrases: married women should be addressed as ba; unmarried “girls” as co; children, girlfriends, or wives as em; male friends and male servants as anh; and servants as chi. Cainay la trai xoai means “It’s a mango”; Ong ay la nguoi tot is how to say “He’s a good man.”

Soldiers reading this advice could get the mistaken idea that they were going to a tourist destination with a bit of violence on the side. Telephone operators outside the main cities may speak only Vietnamese, and “Don’t be too handy with your camera” among tribespeople. Although “The music of Vietnamese will be most strange to your ears until you get used to it,” the guide advised them, “Should you get a chance to go to the theater you may enjoy the cai long, or modern form, more than the hat boi, or classical style.” Unintentionally, this is good advice. In 1965 I was standing in a South Vietnamese village next to John Paul Vann, a CIA-connected American of long experience in the country (who later was the subject of Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam). We were watching a traditional puppet show in which a Vietnamese soldier was knocking about a pale-skinned foreigner. As the audience cheered and laughed, Vann, who would later be killed in a helicopter crash and his body stripped of valuables by South Vietnamese rangers, said, “That’s us being smashed.”

Part of a series begun in World War II for American GIs going abroad, A Pocket Guide to Vietnam was intended to introduce them to the customs, and, rather lightly, the dangers of the place where they were headed. First issued in 1962, it was revised in 1966 and has now been republished by Oxford’s Bodleian Library, with an introduction by Bruns Grayson, a veteran who arrived in Vietnam in 1968 and was given the booklet. Grayson describes the average soldier handed the Pocket Guide as “about twenty years old, not well-educated, not wily enough to avoid the draft in most cases, very often on his first trip away from the United States. I don’t know what the Vietnamese equivalent of ‘overpaid, oversexed, and over here’ was…such a phrase would have described almost all of us.”

But the young, uneducated soldiers described by Grayson also had to be told why they were going to Vietnam, from which, after all, they might not return. “It is interesting,” Grayson writes, “that the booklet accurately and briefly describes the history of the Vietnamese resisting outsiders—the Chinese and others—while assuming that we could never be cast in this light.” To do this required telling some of the same lies that the government was telling the public and, for the most part, telling itself. The editor at the Bodleian Library, which holds a collection of these guides, told me that the purpose of republishing A Pocket Guide to Vietnam now “is to show how propaganda was used by the education division of the Department of Defense.”

Here are some examples:

“The Vietnamese have paid a heavy price in suffering for their long fight against the Communists.”

The suffering began in the nineteenth century with their struggle against the French, which continued until 1954. In the final years of French rule, the US paid 80 percent of their military costs.

The US is “helping a brave nation repel Communist aggression.”

Actually, Vietnam was “provisionally” divided at Geneva in 1954, expressly not into two nations. Although present in Geneva, the US refused to sign the Final Declaration. The Communists claimed they were fighting to implement it.

“From 1956 to 1963 South Vietnam was governed under a constitution modeled in many respect on those of the United States and the Philippines…”

In its May 13, 1957 issue Life magazine, a supporter of the anti-Communist struggle, stated, “Behind a façade of photographs, slogans, and flags there is a grim structure of decrees, political prisons, and concentration camps…The whole machinery of government [in South Vietnam] has been used to discourage active opposition of any kind from any source.”

Advertisement

“The Viet Cong have neutralized the people’s support for the Government in some rural areas by a combination of terror and political action.”

The Vietcong certainly assassinated their enemies but the best-informed literature shows something far more profound. In his two-volume history The Vietnamese War, the RAND Corporation’s David Elliott wrote “Whatever one’s view of the outcome, in the end it was fundamentally decided by the Vietnamese themselves, bringing to a close 100 years of foreign intervention.” In my review of Elliott’s work I commented, “The Rand Corporation’s subjects [ie the South Vietnamese] regarded the Saigon government as corrupt, oppressive, and as the puppets of foreigners; the Americans, who were wrecking the villages, were remembered for having allied themselves with the French.”

It is possible that such falsehoods were believed by the author of the booklet, who in matters of Vietnamese culture was not uninformed. In 1968, James C. Thomson Jr., who had worked in the National Security Council from 1961 to 1967, wrote: “In the first place, the American government was sorely lacking in real Vietnam or Indochina expertise. The more sensitive the issue, and the higher it rises in the bureaucracy, the more completely the experts are excluded…”

American soldiers now serving in Afghanistan receive a handbook that introduces cultural lessons. According to The New York Times, “The manual includes a chapter titled ‘Cultural Engagements,’ offering guidance to small-unit leaders on building relationships with wavering village elders and trust among distrustful village residents…” Soldiers, however, are primarily interested in staying alive. I doubt whether they take this handbook seriously; cultural and historic awareness is probably no greater than it was in Vietnam. In Cables from Kabul, his memoir of his time as British Ambassador to Afghanistan (2007-2009), Sherard Cowper-Coles quotes James Thomson (without attribution) and then adds, “The parallels need no amplification.”

A reprint edition of A Pocket Guide to Vietnam, 1962 is published by the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford and distributed by The University of Chicago Press.