Gracefully off-kilter, stylized as semaphores, the shadow of a man and an outlined woman are positioned at the center of a sea shell spiral. Are they dancing on air—or falling into the void?

The poster for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo is scarcely less haunting than the movie. I first saw the image, without understanding what it was, as a nine-year-old on summer vacation and carried the memory with me for some twelve or fifteen years before I first saw the film. It was, as the filmmaker Chris Marker—one of Vertigo’s most ardent admirers—might say, a memory of the future.

As Vertigo is the most uncanny of movies, it feels more than coincidental that on August 1, two days following Marker’s death, at ninety-one, in Paris, the British film journal Sight and Sound announced, with no little fanfare that, after forty years, his favorite movie had finally dethroned Citizen Kane atop the magazine’s once-a-decade critics poll.

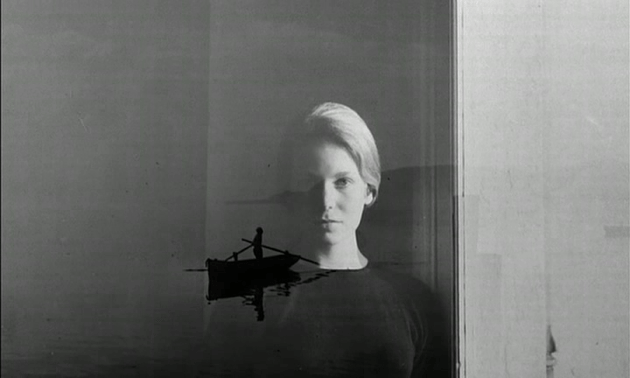

Kane is the movie that hyper-dramatized the act of filmmaking. Vertigo is about film-watching in extremis—the state of being hopelessly, obsessively in love with an image. Unlike Kane (or Psycho for that matter), Vertigo was not immediately recognized as great cinema, except in France by people like Marker. Steeped as it is in the pathos of unrecoverable memory, Marker’s La Jetée (1962) was probably the first movie made under Vertigo’s spell.

Tied for fiftieth place (one vote ahead of Rear Window) in the Sight and Sound poll, La Jetée is Marker’s most generally known work, in part because it was remade in the mid 1990s by Terry Gilliam as 12 Monkeys. Marker was the opposite of a celebrity; he was famous not for his well-knownness but for a certain willful unknowability. The man born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve was permanently incognito. He allowed few interviews and carefully concealed his personal life; although he turned his camera on countless people, including several fellow filmmakers (Andrei Tarkovsky, Akira Kurosawa), he never allowed himself to be photographed.

I called Marker a “filmmaker” but it would more accurate to term him a “film artist.” His oeuvre encompasses movies, photography, videos, TV series, CD-ROMS, computer games, and gallery installations. Some of these might be considered memento mori, often for the film medium. Others propose cinema as a model for historical consciousness. “We can see the shadow of a film on television, the longing for a film, the nostalgia, the echo of a film, but never a film,” is a characteristic Marker observation; one of his favorite aphorisms is borrowed from George Steiner: “It is not the past that rules us—it is the image of the past.”

At once unsentimentally au courant and fixated on that past, Marker was the Janus of world cinema. His unclassifiable documentaries treat memory as the stuff of science fiction, a notion he shared with his early associate Alain Resnais. Hardly a Luddite, Marker thrived on technological paradox. A half-hour succession of still images evoking motion pictures as time travel, La Jetée could have been made for Eadweard Muybridge’s nineteenth-century zoopraxiscope.

For much of his life, Marker functioned as a foreign correspondent, a romantic leftist in the Malraux mode travelling the world from West Africa to Siberia. Most of his early films were personal travelogues—short features notable for their wry, poetic voiceover narration and serendipitous approach to foreign societies. “Modern adventure, Marker understands, is not updating lost paradises, but discovering new places,” observed Cahiers du Cinéma critic Andre S. Labarthe in 1961. “No longer the Indies, but Communist China, no longer the Amazon, but Cuba, no longer Palestine, but Israel.” Today one might call these places failed utopias—or, perhaps, in a more Markerian formulation, places haunted by their lost futures.

La Joli Mai (1963), made in collaboration with cameraman Pierre Lhomme, was another sort of journalistic investigation—an epic of inquiring photography in which, approached on the street in the midst of life, Parisians held forth on their notions of happiness and sense of personal destiny as the prolonged war in Algeria and France’s status as an imperial power came to an end. The single voiceover gave way to the multitude.

Although often termed cinema verité, La Joli Mai was more in the nature of a philosophical inquiry—a time capsule that preserved a particular moment. In the late 1960s, Marker lived aggressively in the present. He was among the most engaged of French filmmakers, co-founder of a film collective that, among other things, produced the agit-prop omnibus Far From Vietnam (1967), which a number of French filmmakers, including Godard, Resnais and Agnès Varda, expressed their opposition to America’s war.

With the decline of the New Left, Marker turned reflective, producing two essayistic historical epics, A Grin Without a Cat (1977; amended in 1988) and The Last Bolshevik (1993), both assemblages of found footage, overlaid with mordantly humorous commentary at once impressionistic and analytical, rueful and resolute. Each in its way, these films dealt with the fate of twentieth-century revolutionary aspiration, as well as Marker’s philosophical and aesthetic debt to the Soviet montage theorists of the 1920s and 1930s. (Marker began as an editor and, in his faith that montage produces meaning, is the heir to Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Vertov.)

An account of French politics from the tumult of ’68 through the 1977 break-up of the Communist-Socialist alliance, A Grin Without a Cat is cinema of temporal striation, layering TV reports, guerrilla newsreels, government propaganda, and interviews to create an all-over account of what Marker cleverly calls the Third-World War. A Grin Without a Cat begins by evoking Battleship Potemkin and, although hardly propaganda, continues in that tradition—a “dialectical montage” featuring a mass hero. Unlike Eisenstein, however, Marker is not out to invent historical truth so much as search for it.

The Last Bolshevik, which encompasses much of the “short twentieth century” defined by the Russian Revolution, is Marker’s long goodbye to its utopian dreams, political and aesthetic. The epistolary voiceover (written but not spoken by Marker) that ponders the accomplishments of Soviet cinema, as well as the disappearance of the Soviet Union, through the prism of director Alexander Medvedkin (1900-89), a onetime cine-activist who managed to survive longer than anyone of his generation, perhaps even with his illusions intact. There is a sense in which, reediting and recontextualizing the work of Soviet directors, Marker produced The Last Bolshevik Movie.

In between these historical ruminations, Marker made Sans Soleil (1982), his quintessential film. Obliquely autobiographical, charmingly aphoristic, and continuously self-analytical, Sans Soleil is, in one sense, a fictionalized exotic travelogue—Pierre Dominique Gaisseau’s documentary about New Guinea, The Sky Above – The Mud Below, as scripted by Jorge Luis Borges—although Marker’s primary subject is what then seemed to him the world’s most advanced society, Japan. In another sense, Sans Soleil is a playful exercise in what Kuleshov called “creative geography,” using footage culled from stock libraries, Japanese TV, Hollywood features, Pac Man, video synthesizers, and mainly Marker’s own outtakes, to create a bridge between the opening shot of three Icelandic children frolicking through a summer field and the closing image of the same town several years later, buried up to its church steeple in molten lava.

The editing is dense and supple and, like all of Marker’s films, Sans Soleil has a voiceover narration; the images (which are often images of images) are annotated by a woman reporting on the letters she’s received from a peripatetic cameraman who is obviously Marker’s alter-ego. The mood is nostalgic and forward looking. A speculative evocation of the global village, with Tokyo projected as a comic-book futuropolis, Sans Soleil often suggests an optimistic version of Blade Runner (released the same year) with which it recently tied for sixty-ninth place in the Sight and Sound poll.

La Jetée is filled with references to Vertigo. Sans Soleil contains a section consecrated to it. Marker—or rather his camera—undertakes a pilgrimage to Hitchcock’s remaining San Francisco locations. “He wrote me,” the narrator says, speaking of the imaginary documentarian who is supposed to not be Marker, “that only one film had been capable of portraying impossible memory… In the spiral of [its] titles, he saw Time covering a field ever wider as it moved away, a cyclone whose present moment contains, motionless, the eye.” This vision of vision was the great subject of Marker’s life.

On Sunday, August 26, Light Industry (155 Freeman Street, Brooklyn) is holding a free, all-day screening of Marker’s films, including Sans Soleil, La Jetée, Le Joli Mai, A Grin Without a Cat, Letter from Siberia, and The Last Bolshevik. Marker’s 1997 CD-ROM installation Immemory will be on exhibit at the Museum of the Moving Image (36-01 35 Avenue, Queens), from August 25 through September 30, as part of an exhibit I co-curated in connection with my book Film After Film: Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema?