“You have an idea of how your life will turn out,” muses Mindy Lahiri, introducing herself in the pilot episode of Fox’s new sitcom The Mindy Project which debuted in September. “When I was a kid, all I did was watch romantic comedies in our living room while I did my homework,” she tells us in voice-over as we see clips of her at various ages watching videos of When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and Four Weddings and Funeral. She kept watching romantic comedies obsessively through college, and while she managed to finish medical school and become an OB/GYN, her love life has not turned out to be like the movies—she was recently dumped by a long-time boyfriend, and just last night humiliated herself at his wedding with a vengeful, drunken toast in which she suggested that his Serbian bride was a war criminal.

The Mindy Project, created by comedian and writer Mindy Kaling, who also stars as the fictional Mindy, is staging television’s version of the quixotic plot. Mindy might love watching When Harry Met Sally, but she is a character in a television sitcom, not a Hollywood romantic comedy, so we can be pretty sure that her own romantic life is going to be different from Sally Albright’s: Mindy is going to be unlucky in love. Not just in the pilot episode or during the first season, but probably for years, or as long as the show is renewed. Even if she starts seeing someone seriously, the relationship will be volatile and probably won’t last more than a season or two, at most.

Sitcoms like The Mindy Project, of course, are at least as convention-bound as romantic comedies like When Harry Met Sally. But because of the conditions of their production, they tend to have something in common with life itself: no one knows in advance when they’re going to end. The full arc of a TV series is not usually mapped out in advance, the show is subject to abrupt cancellation, and there is no artistic consensus on how to handle its conclusion even when writers know that the end is coming; a television series might have an elaborate finale or simply finish out a given season without fanfare. All this gives most sitcoms a certain sense of indeterminacy—we’re bound for no obvious destination—that also applies to the characters’ relationships. As long as each episode has its own tidy, reassuring little ending, audiences tolerate a great deal of open-endedness when it comes to the hero or heroine’s romantic life. And what those tidy little endings are reassuring us about, much of the time, is the fact that the characters are not alone even when they remain romantically unattached and hapless; they have friends, family, colleagues—stability, in other words, even without being married. Sitcoms offer a salve for the bruises of urban single life.

They inadvertently offer a harder-edged truth as well. Sitcoms rarely ask us to believe that any particular couple is, as they say, meant to be. Like romantic comedies, sitcoms might nurture and draw out a sense of chemistry between two characters while also putting obstacles in their way, setting us up for a long-deferred union. (Sam and Diane on Cheers, Ross and Rachel on Friends, for instance.) But romantic comedies traditionally end at the moment the obstacles are overcome and love is declared. They leave us aglow with a sense of the couple’s felicity. In sitcoms, the story must go on well past the first round of obstacles. As often as not, couples break up and the characters have other affairs, and for good reason. Happy couplings are notoriously difficult to pull off; script writers, used to working in a mode of farce, struggle to find the right tone for domestic satisfaction (think of Niles and Daphne finally married on Frasier). Like any kind of comedy, a sitcom can have a marriage at its very end, but a marriage somewhere in the middle is narrative disaster. And since sitcoms are, effectively, comedies without end, it’s hard to write a marriage into the show in a way that encourages—rather than dashes—our illusions of its rightness.

I started thinking about the peculiar demands of the sitcom romance while reading Yael Kohen’s We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy. The book is mostly an oral history of stand-up and sketch comedians, but Kohen also includes a chapter on women’s roles in sitcoms. She focuses on That Girl (1966-1971) and The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-1977), two shows that were initially resisted by network executives because the lead characters had unorthodox domestic arrangements: they lived alone. A handful of earlier sitcom characters had been unmarried working women (Sally Rogers, the comedy writer on The Dick Van Dyke Show, or Susie MacNamara, the lead character of the 1950s sitcom Private Secretary), but in That Girl and especially in the more daring Mary Tyler Moore Show, the heroine’s independence was an explicit focus of the show. This was enough to give television executives, far more conservative than film executives or publishers, some serious qualms. (In the same years that The Group was a bestseller, television writers were not allowed to use the word “pregnant.”)

Advertisement

That Girl starred Marlo Thomas as a free-spirited woman in her twenties trying to break into acting in New York. “We had to have Ann Marie look somewhat normal,” Thomas recalls in the book,

I mean, who’s she connected to? She’s not connected to her parents. She’s moved out. She’s got to have a boyfriend….we didn’t want her to look like a slut, right? So we had to have her have a guy…She couldn’t just be this girl that had nothing.

Even with the precaution of a steady boyfriend, “the network was very concerned that Ann Marie not look like she was sleeping with her boyfriend, Donald, so the show usually had to end with him leaving the apartment.”

And yet, in a way, there seemed to be no question that Ann Marie would be single; the point of the show was that it would have a female character at the center, and no one, it seems, could quite imagine a married woman at the center of anything. At the same time, the very novelty and interest of the show was in her being a single woman; it would be hard to make a fresh sitcom subject out of a young man’s New York bachelorhood if he, like Ann Marie, already had a steady companion that he planned to marry. (Imagine if this hypothetical bachelor didn’t have a girlfriend. I venture that in the mid-Sixties, when That Girl was launched, it would have been just as hard to get approval for a show about an unattached young man. Why is he single? Is he a cad? Is he gay? Is he some kind of loser? The possibility of these delicate questions hanging over our bachelor hero would surely have discomfited network executives, even in the age of Playboy.)

We Killed describes the making of That Girl as a triumph over sexism—and the creators certainly had to battle a lot of sexist assumptions about what kind of roles women could play in prime time. But it’s also true that single life as we see it on television today—a parade of different love interests and dates and hook-ups—was simply not an acceptable premise for broadcast television comedy in the mid-Sixties, regardless whether the star was a man or woman. In life, single men might have had a greater margin of freedom and respectability than single women, but their presumed pastimes could not be dramatized for the family audience at home. Since then, single life has, paradoxically, been domesticated.

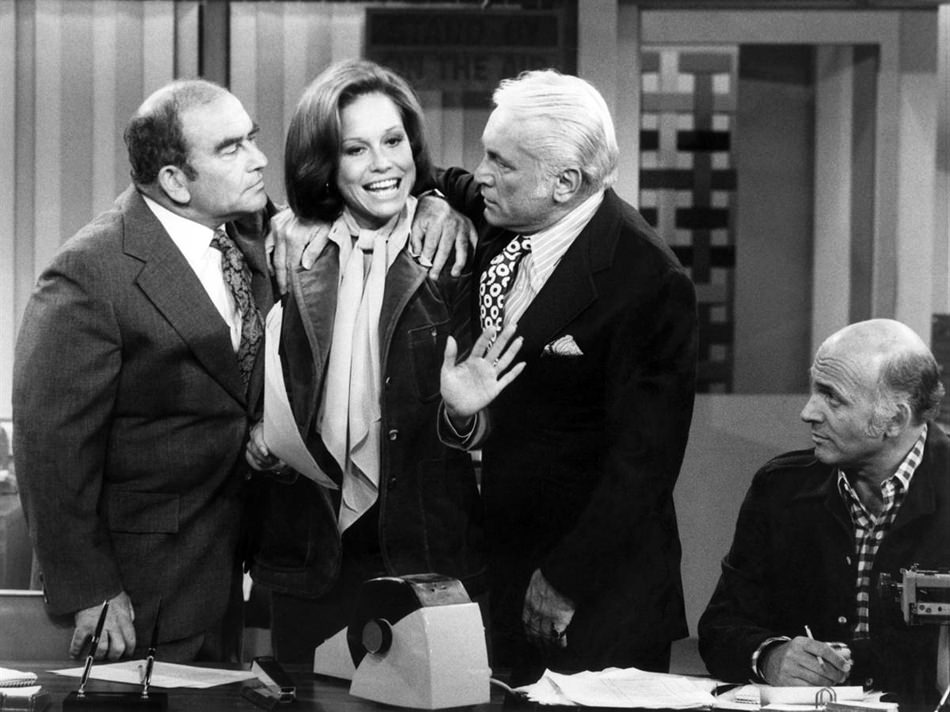

The Mary Tyler Moore Show was the first to make a subject out of a single woman’s romantic life. Moore’s character, Mary Richards, was thirty and didn’t have a steady boyfriend. She was initially going to be a divorcee, but the head of CBS programming balked at the idea. (Television network executives, often seen brandishing focus group transcripts, are the comic foils in We Killed; The Mary Tyler Moore Show co-creator Allan Burns recalls the CBS head of programming telling him that “We have found that there are four things that American television audiences won’t accept: men with mustaches, people who live in New York, Jews…and divorce.”) Instead, Mary Richards became someone who was just ending a long-term relationship with a live-in boyfriend. To Burns and his co-creators, there was an exciting realism and urgency in

the idea that people have these long affairs with the man or woman they think will be the love of their life, and it turns out not to be, and they end up alone again, which became the overriding issue, I think, on the show. This woman who finds that she’s not alone, that she’s got this family of people whom she works with.

The idea of being not-alone even when your relationships and dates end in shambles—this would become not only the overriding issue of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, but of pretty much every subsequent sitcom about single characters. Three decades later, it’s easy to rattle off a list: Cheers, Golden Girls, Living Single, Seinfeld, Friends, Frasier, Will & Grace, 30 Rock, The Office—plus cable sitcoms like Sex and the City, Girls, and Louie. One interesting effect of the genre is that, over time, it has taught us to prefer romantic deferral to fulfillment—at least within sitcoms themselves. Watching the same characters for weeks and years gives us plenty of time to think about what we like and don’t like and hope to see on a show; watching a variety of shows over years and decades has made us experts in sitcom conventions and brought to our conscious awareness the pleasure of seeing relationships stymied and dates gone awry. All of which has upset the traditional balance between necessary postponement and obligatory resolution that we know from film.

Advertisement

One of the best romantic comedies of recent years, Up In the Air, is great precisely because it foils our expectations of felicitous union, and it suggests that the richest possibilities for the film genre might lie in a more wised-up approach. If that turns out to be true, then sitcoms will have made a significant intervention in the conventions of romantic comedy—which is pretty surprising, coming from a form of entertainment overseen by men in suits studying Nielsen results.

We’ve long known that the credulous viewer of romantic comedy is headed for a fall, for comedy encourages a misunderstanding about endings. In life, the “ending” that is marriage actually comes at the beginning of adulthood. The novel took as one of its great subjects the calamitous realization that you have to live with your marriage. Now that we don’t really have to live with our marriages, or enter them in the first place, the choice of whom, if anyone, to settle down with is not a great subject but a middling one—about sitcom-sized, it turns out. And the grown-up questions we ask ourselves when deciding whether to stay or go, to marry or not, don’t hinge quite as much on the idea of a right or wrong choice as on a rough sense of timing: when, if ever, is the right time to write the marriage into our lives? How much felicity can we plausibly expect from a partnership entered in our youth? Would we lose too many potentially interesting plot twists if we committed to one person right now? And if we end up disappointed by marriage, will it have been because we chose the wrong man, or simply that we chose him when we were only about a third of the way through our own personal comedies?