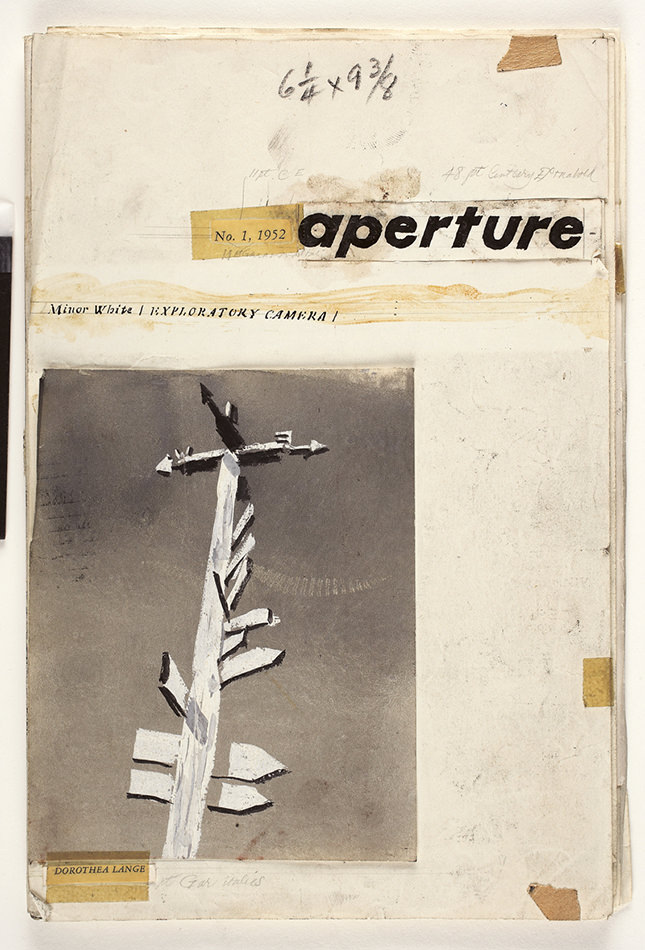

Aperture magazine, which just celebrated its sixtieth anniversary, has published Aperture Magazine Anthology: The Minor White Years, 1952-1976, a marvelous anthology devoted to Minor White, its founder and long-time editor, that collects the best of the critical writings on photography that appeared in the magazine in those years. Leafing through its pages and seeing the familiar cover photographs brought back many memories, since I worked for Aperture between 1967 and 1970 and played a small part in the production of eleven issues of the magazine and a few books.

I had heard about a job there, after several weeks of searching unsuccessfully for work in New York, through a friend of my father’s who did bookkeeping for the magazine on a part time basis. I remember arriving at the address I had been given, East 91st Street and Lexington, wearing a dark blue suit, a white shirt, and a red tie and expecting a slick modern office. Instead, I found a rundown brownstone whose second floor apartment, with a living room, bedroom, and kitchen, had been turned into what easily could’ve been mistaken for a down-at-the-heels lawyer’s office or a detective agency. Michael Hoffman, the publisher and managing editor, who was four years younger than I was, had his desk in the former living room, while the bedroom had some filing cabinets and two small desks: one of them was used by my father’s friend when he dropped in a couple of times a month; the other was to be mine. The kitchen in the back had been converted into a mailing room and storage space whose shelves were lined with past issues of the magazine and the couple of books we published. And that’s all there was.

I’ve no memory of the interview. Most likely I told Michael about myself, my ten years of going to night school to get a bachelor’s degree in Russian Language and Indo-European linguistics, and the jobs I held during the day as a payroll clerk, shirt salesman, bookkeeper, bookstore clerk, proofreader for a newspaper, and house painter. I had just published a book of poems, so that may have come up too. I took the job, even though the pay was miserable.

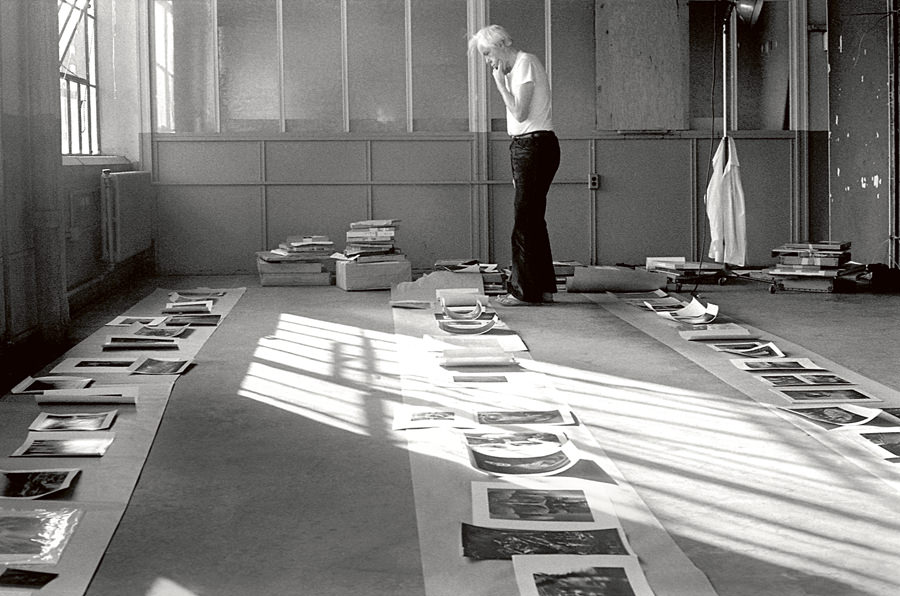

What I remember vividly about that first day was the shocking untidiness of the office. It was not easy to find a place to stand or sit, since books and photographs covered every chair and most of the available floor space. It was commonplace to hear first-time visitors exclaim as they came through the door: “This place is a firetrap.” That was not to be our main worry, I soon discovered. Inevitably, given the total mess, we spent a lot of our time looking for a letter or a photograph. Minor White would be on the phone or a famous photographer would come in unannounced and panic would ensue. I once found some photographs by W. Eugene Smith that had slid behind a radiator, while he stood chatting amiably with Hoffman, oblivious to my desperate search behind his back.

Though I was listed on the masthead of the magazine as “business manager,” I did everything that needed to be done around the office. I answered the rare phone calls, opened and answered mail from subscribers, swept the floor, paid the bills, delivered proofs to the printers, and was on call for various emergencies when an issue was in production, since there were no other full-time employees. These visits to the printers, engravers, and compositors—who in dimly-lit lofts with grimy skylights and windows in lower Manhattan and Brooklyn plied their trade using old-fashioned letterpresses with the skill to achieve the range and depth of tone in the black-and-white photographs we published—were especially memorable. One entered a world that had hardly changed in a century to be met by some gaunt, ghostly-pale old man who looked like a character out of Dickens, who would then be joined, as he squinted over the image I had brought, by two equally venerable fellow workers. They would study it a long time, hardly exchanging a word, until one of them would indicate an area of the photograph with his finger and another one of them would either shake his head or nod in agreement.

With Minor White teaching and living in Boston and Hoffman spending a great deal of time in Philadelphia’s Museum of Art, where he was a curator, there were plenty of slow days in the office, and I passed the time looking at photographs. In addition to the back issues and books we published, there were at any given time dozens of portfolios around the office that had been submitted to the magazine by both unknown and well-known photographers. Once in a long while one of them would actually turn up in person to make inquiries about a submission, only to be told by me that neither our publisher nor our editor were available and were not likely to be in the office in the near future. They’d stand there baffled, unsure what to do next, so I had to repeat what I said over and over again till they understood.

Advertisement

I recall an elderly man in a brown double-breasted suit who claimed to have traveled by bus with his portfolio of photographs all the way from North Dakota. Another time, two blond, angelic young men, who appeared to be identical twins, came through the door. They showed me a series of nude color photographs of themselves and a couple of young girls who also appeared to be twins. While one of the boys took the pictures, the other three would laze completely uninhibited on some gorgeous summer meadow, or they would be seen bathing in a mountain stream, smooching and making love. My instructions were to have photographers leave the work they brought along if it looked promising, and this illustrated teenage Kama Sutra certainly did, since these boys were obviously familiar with the nudes of Edward Weston and knew how to take a photograph. (As far as I remember, none of these or other unsolicited photographs was ever published in the magazine.)

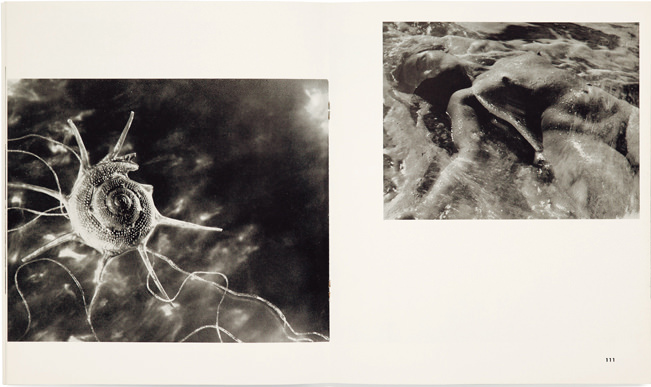

In one of the older issues, Minor White had an essay called “What is Meant by ‘Reading’ Photographs” that made a big impression on me. He writes in it about hearing photographers often say that if they could write they would not take pictures. With me, I realized, it was the other way around. If I could take pictures, I would not write poems—or at least, this is what I thought every time I fell in love with some photograph in the office, in many cases with one that I had already seen, but somehow, to my surprise, failed to properly notice before. There is a wonderful moment when we realize that the picture we’ve been looking at for a long time has become a part of us as much as some childhood memory or some dream we once had. The attentive eye makes the world interesting. A good photograph, like a good poem, is a self-contained little universe inexhaustible to scrutiny.

I recall rainy afternoons with nothing to occupy me in the office but some photograph by Dorothea Lange, Paul Caponigro, Jerry Uelsmann, or by a complete unknown that I couldn’t stop looking at, because it seemed to grow more beautiful and more mysterious the longer I kept looking. Then, abruptly, a phone would ring with some irate subscriber shouting that his issue arrived damaged in the mail, and the spell would be broken.

Aperture Magazine Anthology: The Minor White Years, 1952-1976, edited by Peter C. Bunnell, is published by Aperture. A redesign of Aperture magazine is launching this month.