Last night’s dream: “The Forest of Misplaced Inventory,” said the dream voice. “That shouldn’t take much description!” The visual was a stack of shrink-wrapped red plastic garbage-can lids in a stand of green spruce trees.

It must have been a writing dream. I sometimes have those. But what was it trying to tell me? Dreams often pun: Was the key word invention? Has my invention inventory been mislaid somewhere among the synaptic neuron branches? Will I find out later? In a novel I probably would, but life isn’t a novel, and vice versa.

The best writing dream I ever had was in the mid-Sixties. I dreamt I’d written an opera about a nineteenth-century English emigrant called Susanna Moodie, whose account of her awful experiences, Roughing It In The Bush, was among my parents’ books. It was a very emphatic dream, so I researched Mrs. Moodie, and eventually wrote a poem sequence, a television play, and a novel—Alias Grace—all based on material found in her work. But that sort of dream experience is rare.

The worst dreams I’ve had are ones in which people I know are dead. Increasingly, people I know are dead, but sometimes they reappear in dreams, on hilltops or sidewalks or even on television screens, to assure me that there’s more to being dead than meets the eye; and I find this comforting. I’m told I am not alone: the dead often return in dreams. The folk songs were right.

Most dreams of writers aren’t about dead people or writing, and—like everyone else’s dreams—they aren’t very memorable. They just seem to be the products of a psychic garburator chewing through the potato peels and coffee grounds of the day and burping them up to you as mush. If you keep a dream journal, your mind will obligingly supply you with more dreams and shapelier ones, but you don’t always want that, nor can you necessarily make any sense of what you may have so vividly dreamt. Why, for instance, did I dream I had surged up through the lawn of Toronto’s Victoria College and clomped into the library, decomposing and covered with mud? The librarian didn’t notice a thing, which, in the dream, I found surprising. Was this an anxiety dream? If so, which anxiety?

Dreams have always fascinated us. They feature in the Bible, in the Greek myths, and in the traditional lore of almost every culture on earth. They’ve also baffled us: What do they mean? How do we know? Why do we care? Because we do care about our dreams, from time to time: a happy one can lift the spirits for a day, a sad one can depress.

The allegorical dream vision was a staple of the high middle ages, and dream visitations are common in folksong, but characters in the developing novel form didn’t dream frequently—or such is my impression—in the eighteenth century. Nor do they, much, in the early nineteenth century: Jane Austen’s folks don’t dream. Poets do, from the Romantics on, but that was seen as poetic. The realistic novel stuck to what people did and thought while awake.

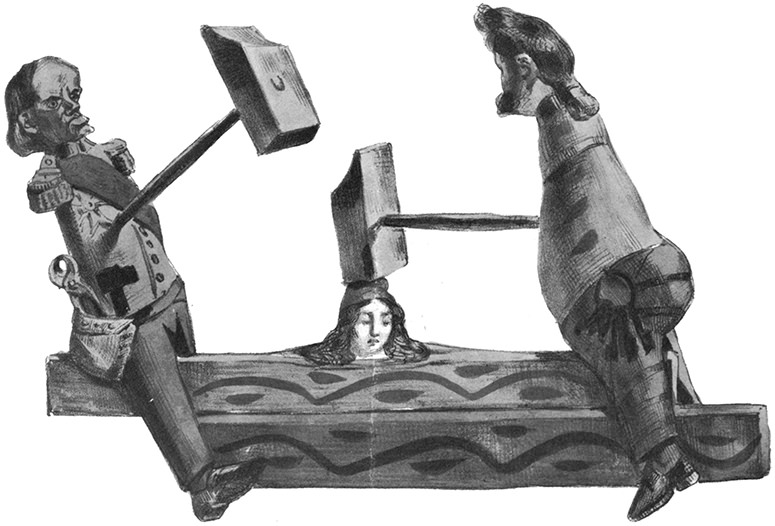

But in addition to its industrial revolution and its build-out of capitalism, the nineteenth century was obsessed with hidden aspects of the self—mesmerism, somnambulism, multiple personalities, trance, possession, mind-altering drugs and hallucinatory experiences, hypnotism, spiritualism, Swedenborgianism, and more. Pre-Freudian medical investigators of the mind and brain: where do we go when we sleep? The mainstream realistic and naturalistic novels of the age don’t make much room for this third of our lives, though in what would now be called “the genres” there was an astonishingly rich effervescence of mind-related oddities. Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, A Christmas Carol, the tales of Sheridan LeFanu, Alice in Wonderland, The Turn of the Screw, and a large grab-bag of accomplished ghost and horror stories were thrown up like mushrooms from the subsoil of the hidden Victorian mind.

But it was mainly after Freud that dreams became acceptable, not only as a major fuel for surrealism in painting, but also in mainstream fiction, as a guide to the characters’ complexes and neuroses, which for a while became characters in themselves. And not always for the best. We can get far too much of other people’s dreams.

Should you, as a fiction writer, permit your characters to have dreams? Some think it’s a bad idea, but there’s no reason why not: people do dream, they dream every night, so to have characters who don’t dream at all is like having ones that don’t eat. But that’s all right, too: some stories are not about dreaming and eating. We would be taken aback if Sherlock Holmes or James Bond or Miss Marple suddenly burst into dreamspeak, though newer generations of crime and thriller heroes are now—I note—permitted more of a personal life. Which can include more of a dream life. But not much more. You wouldn’t want the dreams to get in the way of the corpses.

Advertisement

So let your characters dream if they must, but be advised that their dreams—unlike your own—will have a significance attached to them by the reader. Will your characters dream prophetically, foretelling the future? Will they dream inconsequentially, as in real life? Will they use accounts of their dreams to annoy or attack or enlighten the other characters? Many variants are possible. As in so many things, it’s not whether, but how well.

Towards the end of her life, when she was already blind, my mother told me about a dream she’d had. She was on a canoe trip—something she’d loved doing—but suddenly no one else was there. It was totally silent; she was all by herself, climbing up a hill of bleached sticks. This dream impressed her enough that she told me about it, which wasn’t usual for her. What was she trying to convey? That she was frightened, I think. That she was sad. That she felt alone.

After she was dead, I put my mother’s dream into a story, which she must have known I would do. She understood, by then, what manner of creature I was.

Part of a continuing NYRblog series on dreams. Other recent contributions include Pico Iyer’s “Cities of Sleep,” Francine Prose’s “Chasing the White Rabbit,” and Tim Parks’s “My Invisible Sea.”