For a period of two or three years during the late 1980s or early 1990s—it’s difficult, now, to recall exactly when, but I know it was while I was a graduate student—I repeatedly dreamt the same terrifying dream. I was then in my late twenties or early thirties, and it had been a long time since I’d had any dreams that I could remember. (One in particular, an ecstatic, buoyant fantasy of sudden flight, used to recur, but that was when I was a small child—six or seven or so, not long after my mother’s mother died, young enough not to be afraid when, one night, I saw her ghost standing by the door of my room, white and smiling and talking to me softly, although I couldn’t make out the words.) But during that strange period when I was struggling to write my dissertation on sacrificial virgins in Greek tragedy—and struggling, too, with the secret thought that perhaps graduate school wasn’t for me, perhaps there was some other kind of writing I ought to be doing—the awful dream came regularly, insistently. Once a week sometimes, sometimes every other week, sometimes twice a week or more, it would (as I then thought) be waiting for me as soon as I dropped off, identical each time in every detail: the open gate, the familiar headstones, the sudden sunset, the missing graves, the dead I knew so well but who didn’t seem to know me any more, chasing me, the gun, the embarrassing horror-movie detail of the silver bullets.

I know that I was in graduate school when I dreamt this dream, because when I finally took my psychotherapist’s advice about how to deal with it and drove the hour and a half from central New Jersey, where I was living at the time, to the cemetery in Brooklyn where many of my family lay at rest, Bill was with me. Bill. Bee-uhhlll, his mother down in Birmingham would say as she left her long messages on his answering machine, and he’d sometimes play them back for me when we stumbled into his dorm room, giggling, my hand already inside the waistband of his boxers while the drawl yawed away in the background. It was Bill who drove us to Brooklyn that day on my therapist’s strange errand, in the boxy beige Volvo his parents had given him, his slim frame barely filling the big bucket seat, which made him look even younger, the lock of dark hair falling over a blue eye; and me next to him, sometimes talking, sometimes silent as we drove to the old Jewish cemetery, always wondering, What on earth must he think of all this?

And then, when we pulled up on the Interboro Parkway next to the low stone wall over which, even now, a decade since my last visit here on a June morning three days after my grandfather jumped in the swimming pool, I could recognize the landmark familiar from those visits years ago, the headstone in the shape of a tree trunk prematurely felled, the grave of the great-aunt who died before her wedding day—habetulah, my grandfather read me the inscription once, a virgin—when we slowed down and I looked over the wall at the graves I thought, What would they make of him?

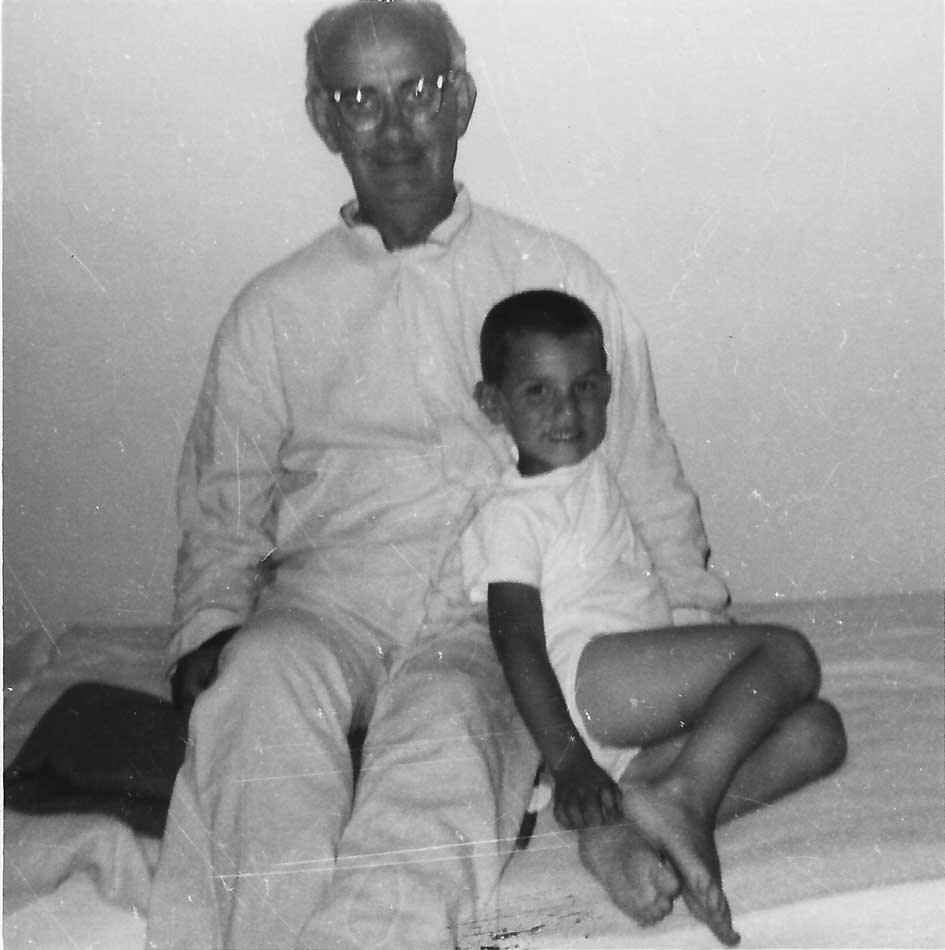

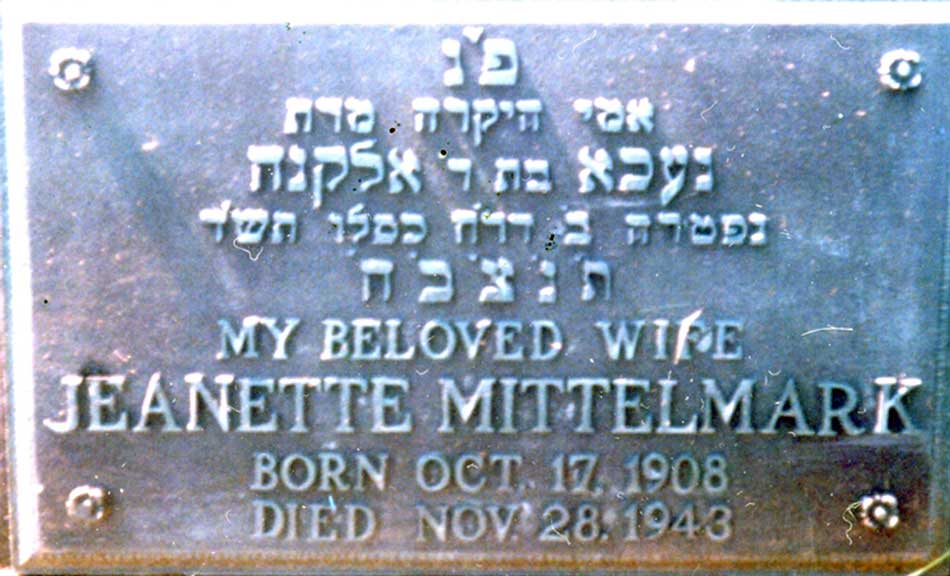

When the dream begins it is morning and I am pleasantly aware—with the complete, unquestioning awareness that it is possible to have in a dream, born fully-grown from our sleeping brains like a character in a myth—that I am going to the cemetery to visit the graves of my relatives as I used to do years before, when I was a child, accompanying my mother’s father, Grandpa: he is there too, now, side-by-side with Nana, a stone’s throw from his mother and a handful of the many tragic siblings, the sister who died at twenty-six, a week before her wedding, another one who died at the Thanksgiving table, the “rich” cousins who had bought the vast plot all those years ago, around which Grandpa would walk, visiting each grave in turn, his silver-covered prayer book in hand, muttering what I thought were prayers but which could have been imprecations….

In the dream, the morning is fine: the kind of weather that would make my mother cry, on Passover or the High Holy Days or the day of someone’s bar mitzvah as we walked out of the house and she would cry out, as the drizzle stopped and the dark green front lawn suddenly went yellow with sunlight, That’s my mother, it is, I know it! The sky is clear and the sun is shining as we pull up next to the low wall and pause by the gate where, as usual, a Hasid waits, a basket of yarmulkes in hand. Give him a coin, something, my grandfather, whose grave I have come to visit in this dream, would say when I was a boy, give epis, he’s a nebuchl, and I would put a quarter in the black-hatted man’s hand and take a black yarmulke, flimsy as the wing of a bat, out of the basket and run past without saying anything.

Advertisement

In the dream, however, I am an adult and unafraid, and so I turn to the Hasid and say, a shaynen dank!, thanks very much!, and the funny thing is that in the dream I think how odd it is, how anomalous, that I’m talking Yiddish with this man. But the day is fine, and I’m happy—this is a pleasant visit—and I move through the gates lightly, preparing to make the left turn onto the first major pathway, already turning my head and scanning the distance for the familiar landmark, the tall tree where the virgin lies at the very back of the big plot, almost at the stone wall that divides the highway from the dead, the tall stone set with an oval porcelain plaque, a photograph of the dead girl, smiling.

And yet the instant I start walking down the path I know that I am now in a nightmare. For one thing, the sun has suddenly set. As I walk I pause to reflect on the strangeness of this abnormally swift sunset, how odd it is that when I stood outside thanking the Hasid it was as fine and sunny as a Passover morning, and now it’s nearly dark. Hurrying my steps, as if the physical activity might calm me, I scuttle down the pathway that leads to the Bolechover section, which I know will be on the left. Bolechover. Like many Jewish cemeteries, this one is haunted by an older geography: however naturalized and Americanized they may have become, the Jews buried here were laid to rest according to the European city or the town, the shtetl, where they had come from. My grandfather’s family came from a little town near the Carpathian mountains called Bolechow; a stone stele at the entrance of this section says Bolechower Association, a legend that also appears on a silver kiddish cup that used to belong to my grandfather and into which, now, I sometimes stick a flower or two, since I have never kept the Sabbath. It is to the Bolechover section that I hurry as, in my dream, the sky darkens ominously and the wind quickens and I know that something has gone terribly wrong.

For when I arrive at the usual spot the graves are gone. The Bolechover section no longer exists: the gate with its Bolechover inscription has vanished, along with the little granite bench that, I imagined, no one ever really sat on. With growing panic, I walk quickly around the once-familiar landscape, section MM, but the gray stone steles and footstones with the bronze plaques bearing the names I know so well, Diamond and Nass and Singer and Mittelmark (the rich cousins), aren’t there; nor are the stones for my grandfather and his mother and siblings, Bubby Yager and Aunt Jeanette and Uncle Julius, each stone with a different spelling of the family name, Jäger and Yager and Jaeger and Jager, all gone, as is the double headstone for Grandpa and Nana, Beloved Husband, Father, and Grandfather; Beloved Wife, Mother, and Grandmother.

Worst of all, for some reason, the petrified stone tree of the long-dead virgin bride is gone, indeed the entire stone thicket of cut-down trees here at the back, all marking the graves of unmarried young women, has vanished, replaced by polished low black stones whose inscriptions I bend over to try to read but, to my consternation, can’t make out. Could it be Russian? But why?

Trying to alchemize my distress into irritation, as I sometimes do in order to calm myself, I walk hurriedly to the homey little cemetery office across the highway and, once inside, start remonstrating with the person working there, who (as in real life) stands behind a knotty pine counter in front of a wall covered with huge maps, meticulously geometrical, of Mount Judah Cemetery, the names of its major thoroughfares (“Machpelah”) and smaller alleys and the sections with their Old Country names picked out, in purplish ink, in the chicly fussy block caps that architects use. I speak angrily with this person, and it is odd to say but I can never recall if it’s a man (like the very nice real-life one who, many years after I stopped having this nightmare, tried to help me with some ideas for a memorial stone I was planning to erect in the cemetery to honor certain relatives of mine who died in Bolechow in the 1940s but were never buried, never had a tombstone) or a woman, like the “snippy” one who, a year after Nana’s death, when the unveiling of her gravestone was going to take place, was rudely impatient over the phone to my mother about an unpaid bill, and Mother coolly replied by saying, “I’m so sorry to be so ignorant about all this, you see this is the first time my mother died…,” and that shut her up but good. (Every now and then my mother enjoys telling stories meant to show how she, with the Jaeger sense of humor, got the better of some crass or uncouth adversary; her father told many more such stories, about himself, although now that I am grown up I ask myself how many were true. I suspect that he was a far more fearful man than he wanted to let on; I wondered, after he died, what had become of the shiny silver-plated BB gun that he kept, wrapped in a soft cloth, in a dresser drawer, the one he said he needed in case the house was burgled… )

Advertisement

Anyway, to this person in the cemetery office, the person of indeterminate gender, I loudly, even wildly complain, my voice hoarse with panic, that my family’s graves have somehow disappeared—even the tree, the famous tree, the resting-place of the Bride of Death. I say this with emphasis, as if the tragic tale were one that everyone knew. Certainly everyone in my family knew it. But the cemetery person is nonchalant, indifferent. He or she informs me that the “older” graves are “regularly discarded” as a matter of course in order to make way for “newer burials that people will actually visit.” Discarded is the word the person uses, and I register this with incredulity—I am aware, in the dream, that I am incredulous—even as I loudly assert that people do visit these older graves, old as they may be. Wasn’t I there, visiting? And anyway (I tell myself), Grandpa died not ten years ago: hardly an old burial. It’s outrageous, I say aloud, and then: it’s against New York State law! I say, I am going to notify the authorities. The person, unmoved, shrugs bureaucratically; then motions on the map toward what I suddenly understand is the “new” section of the cemetery, just as I suddenly understand that our area, the Bolechower area, was in the “old” section. (This is in the dream: there is no “new section.”) “You might try that area, sometimes we move them over there.”

Them.

Frantic, I run to the New Section, which is oddly hilly, planted with new cypresses and evergreens, and drop to my knees at a large gravestone beside a forbiddingly dark green tree. Scrabbling with my hands in the dirt, I dig down into a crevice that has opened up between the base of the stone and the earth into which it has settled. My gorge rises in disgust as I feel the smaller tendrils of the tree-roots brushing against my hands; they feel like dry fingers. I know, again with sudden clarity, that this is the right spot. I’m sweating, the perspiration is running into my eyes; it’s getting harder to see—by now it’s deep twilight—when I feel a little whoof of cool air coming up out of the ground, as if escaping from a locked chamber. Torn between curiosity and terror, I sit back on my haunches, trying to think of what to do next, when I hear a voice behind me. The voice is calling my name, in a familiar accent.

Dehniel, it says. Dehniel.

It’s the voice of my grandfather.

Of course I don’t turn around to look. Instead, I start running, and as I run I miraculously acquire absolute knowledge of two facts. The first is that my grandfather has a pistol filled with round silver bullets, meant for me. The second is that he’s very angry. When I was growing up, Grandpa’s anger was a thing you feared: you didn’t disturb him while he ate his farina, carefully pursing his lips to blow on a spoonful of the hot cereal as the single pat of butter melted in the middle of the bowl, or while he read the paper, or while he davened in the morning, the burgundy-velvet tallis bag with its silver embroidery carefully laid on a chair: no, you never disturbed him. His belt, and the bottom of his leather bedroom slipper, had seen some use. But what I’m thinking about in the dream, as I run blindly back toward the “old” section—for some instinct tells me that, even ransacked and empty, the Bolechover section is somehow safe—what I’m thinking about is this childish thought: that I don’t want to turn around, don’t want to see his face. What will Grandpa look like now, after the swimming pool, after ten years in the ground?

It is this terror, a low fear bred of too many Saturday nights in the 1970s watching “Chiller Theater” and “Creature Features” with my brother Andrew—in the dream, even, I’m aware of a certain embarrassment about this—that possesses me as the first of the bullets whizzes softly past me. And it is at this point, night after night, that I start shouting, the loud wild dream-scream that is, in waking reality, nothing more than a strangled grunt; and wake up.

Naturally when I actually went to the cemetery with Bill that day, our visit was uneventful—pleasant, even. We pulled up by the low stone wall, and from the curbside on the Interboro Parkway of course I pointed out to him Aunt Ray’s grave, the granite tree trunk with its lopped-off limbs. We walked through the entrance, wordlessly took our yarmulkes from the Hasid on duty—Bill giggles as he puts his on; of course it only makes him look more WASPy—and turned left, heading down the quiet path, to the familiar patch of ground, the gates, the forlorn stone bench, the mishpuchah calmly unconcerned with our presence, some of their headstones dotted with pebbles and rocks that other, unimaginable visitors had left as tokens of their visits. As we stepped over the low mounds I’d bend over and clear the ivy away from the inscriptions and tell Bill who was there, how they were related to me, what role they’d played in the turbulent family dramas that my grandfather had lovingly narrated to me when I was young. Grandpa and Nana’s pale gray stone was clean, new-looking as always, smoothly polished. Mar. 23 1902 – June 13 1980. I repeated the dates aloud, recalling that the 13th, the day he’d jumped in the pool, had been a Friday; and remembered the small shiver of embarrassment I’d felt that day, home from my southern university for the summer, when I realized that this awful family tragedy, not only death but suicide, had occurred on a Friday the 13th, like something in a bad horror movie.

Of course we saved the tree trunk for last, just as we had done when I was a child and we’d come here with Grandpa. Standing next to the starved-looking rosebush, I told him the story again, how she had died a week before her wedding, and traced with my fingers the oval porcelain plaque. As I have said, this was in the late Eighties or early Nineties, and so a few years before I started work on my first book, which, among other things, tells of my obsession with this particular tomb; and of how, in the course of some research I did one summer in the mid-1990s in the cool high-ceilinged microfiche room at the New York City Municipal Archives, I dug up some startling information: that the girl under the granite tree wasn’t, in fact, unmarried, habetulah, but had been wed the year before she died; that a week before her wedding was a lie.

But that came later, long after Bill had gone, and certainly we couldn’t guess any of this that day as I touched the smooth cool oval and its silvery-gray image with my fingers and told him the tragic tale.

During my next session with my therapist, I told her about our pleasant but uneventful visit, and naturally we talked again about the dream, which of course she knew well, having heard me tell it many times; naturally we discussed its implications, what it could mean. Was it a guilt dream, was it an anxiety dream, was it about my relationship with my grandfather specifically or my family in general, would he have been disgusted by what I was, would he have cared, what did they think, anyway? Over the next few months we’d discuss all this, naturally, return to the dream and the visit, but as much time and thought as we devoted to it, we never could say that it was precisely this, or that.

But by then it didn’t matter. Other things came to preoccupy us, more urgent worries and challenges, my mother, my father, Bill, the usual things, my dissertation on brides of death, all these things crowded into the foreground, and I was convinced that my dead relatives had relinquished their strange claims on me for good. After all, following my visit to the cemetery that day, however many years ago it was, I’ve never had the dream again.

Part of a continuing NYRblog series about dreams.