On the evening of July 13, the day a Florida jury acquitted George Zimmerman, my mother phoned me, distraught. She, like many mothers of black sons, couldn’t understand how state prosecutors had failed to secure a conviction for the death of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin. She’d heard that the NAACP and other civil-rights groups were pleading for the United States Department of Justice to charge Zimmerman with a federal hate crime; she’d also heard that the family could pursue a wrongful death suit. And this was more than a week before angry protests about the verdict filled city streets around the country. Surely, the Justice Department would be able to do something?

Then she asked me, based upon my experience as a former Justice Department civil-rights attorney, whether I thought either of the possible legal remedies would stand a chance of holding Zimmerman accountable for Martin’s death. My answer didn’t give her much comfort.

Hate crime cases, I told her, are a tricky business. Federal prosecutors might allege that Zimmerman interfered with rights that were protected by federal law; in this case, perhaps, Martin’s federally protected right to walk down the street. Prosecutors may also allege that Zimmerman violated the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, the 2009 federal statute that punishes violent race-based crimes.

Under either statute, federal prosecutors must prove that Martin was killed because of his race. But, like many legal questions, determining whether a crime has been committed “because of race” is no simple matter. Federal prosecutors may try to argue that if Trayvon Martin were white, he’d still be alive today. This argument, in many ways, mirrors an aspect of the Florida prosecution’s theory, an accusation that Zimmerman had “profiled” Martin as a potential troublemaker based on his appearance as a black youth, and on that basis had proceeded to stalk, and eventually kill, Martin. A federal jury might need to hear something more to convict. In fact, some jurors might need the government to present evidence that Martin’s death was motivated by a deep prejudice against African-Americans.

In either case, the government would have to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that race played a role in the death of Martin. In response, Zimmerman has at least two practical defenses. In the first defense, Zimmerman’s legal team might strive to introduce evidence demonstrating that he is not prejudiced against African-Americans. As is now well known, some African-Americans have already come to Zimmerman’s defense. A black neighbor has said that Zimmerman was the first and only person to welcome her to the neighborhood. Black children have also claimed Zimmerman mentored them. And according to his family Zimmerman has many black friends. The defense undoubtedly would try to ensure that the jurors learned these stories. Imagine if these black friends showed their support by sitting behind Zimmerman at trial. This image alone might persuade some jurors that race was not a motivating factor in Martin’s death.

In a second defense, Zimmerman’s legal team might offer an alternative motivation for Martin’s death. Defense lawyers might present evidence that Zimmerman was immature, desperate to become a celebrated hero, a gun-toting failure who didn’t have the stuff to become a police officer. The Florida jury received evidence that Zimmerman, a criminal-justice student, had unsuccessfully applied to become a cop. This immaturity, defense lawyers might argue, shows Zimmerman was motivated by issues other than Martin’s race. One might call this argument the hopeless-loser defense. Zimmerman isn’t a racist, the defense goes, he’s a flop that acted foolishly and overzealously. It may sound silly, but in my experience, this defense can be very persuasive. This nation has its fair share of reckless and thickheaded wanna-be-vigilantes, many of whom are not especially bigoted.

In their assertion that race didn’t motivate Martin’s death, Zimmerman’s lawyers may have an unexpected ally. Daryl Parks, a lawyer for Martin’s family, shocked many by claiming that Trayvon’s death was not about racial profiling. In television interviews following the verdict, Martin’s parents seemed uncomfortable pushing race to the forefront of the national debate. To me, such statements suggest that even some black jurors may doubt race motivated Martin’s death.

My mother groaned. Like many African-Americans of her generation, she views the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division as an unequaled force for social good. After all, this division, so often associated with Bobby Kennedy, desegregated schools, fought disenfranchisement, and prosecuted the Los Angeles officers who beat Rodney King. It only seemed natural that the Justice Department would now pursue this cause. She asked when might we learn their decision. I had more bad news.

Advertisement

Following the Florida court’s July 13 verdict, the Department issued a press release promising to fully review the facts. In my experience, the Justice Department’s review process is cautious and deliberative. Career prosecutors will assess the facts and make a recommendation to political appointees. The department will likely decline to indict unless the political appointees are confident that the case can be won. If the Martin family chooses to bring a civil suit, the department will most likely wait to see the results of that case before deciding whether to move forward. The Justice Department may take weeks, possibly months, to reach its conclusion.

My mother chewed on my answer for a while. But what about the public response to the verdict? The NAACP hopes to send the department a petition urging that charges be filed against George Zimmerman. The petition, she predicted, would easily get hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of signatures. That’s nothing to say of the past weekend’s countrywide protests. Already, cable news channels were broadcasting images of tearful mothers holding picket signs.

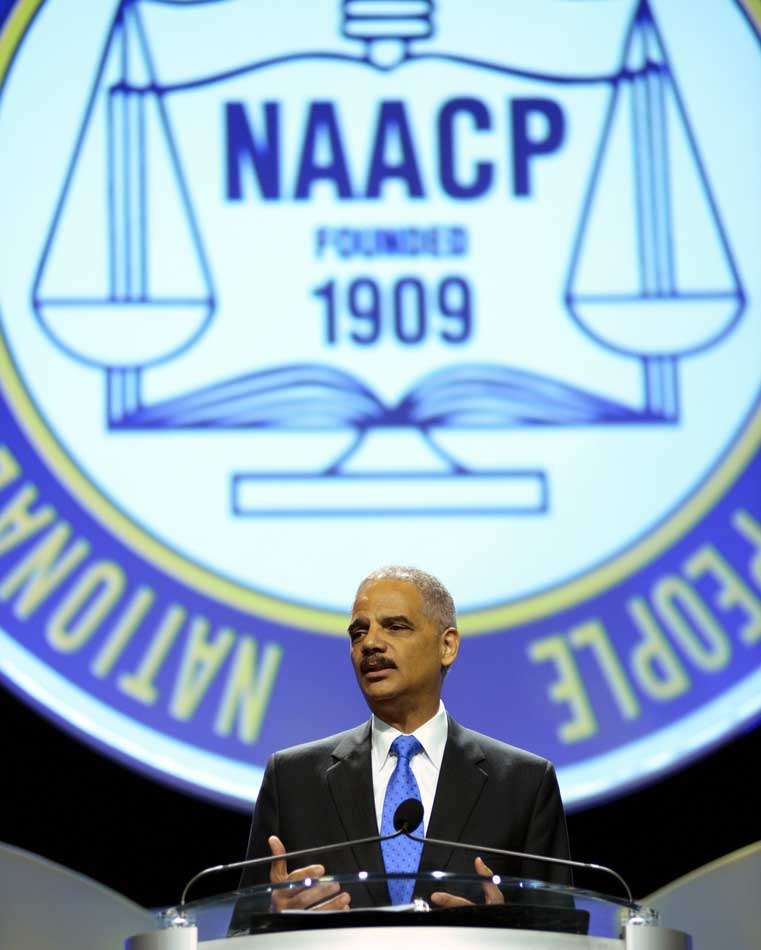

In fact, public sentiment may have little bearing on the case. Yes, Department of Justice lawyers will be aware of the public’s interest. The spotlight may mean the department might give the case special attention, assigning more attorneys than usual, or conducting a more exhaustive investigation. But, as Attorney General Eric Holder would later say, the Justice Department makes decisions based upon the facts and the law. Public pressure cannot, and should not, influence the decision to prosecute.

President Barack Obama, in his own comments about the verdict last week, sought to dampen expectations that his Justice Department might bring a hate-crimes case. The president, a former civil-rights professor, noted that homicide prosecutions are traditionally the purview of state and local law enforcement.

That leaves open the possibility of a civil case. A wrongful-death suit could award Martin’s family monetary damages to compensate them for Trayvon’s death. While this month’s verdict does not help such a civil remedy, prosecutors in Florida had to prove Zimmerman’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. In a civil case, the burden of proof is far lower. The Martin family has the option to claim Martin’s death was either intentional or the result of negligence. The family has already settled a wrongful death claim against the homeowners association of the Retreat at Twin Lakes, the Florida housing complex where Martin died. The family received a reported one million dollars.

Still, a successful civil claim against Zimmerman, as a practical matter, might not accomplish very much. Zimmerman would not be imprisoned; and it remains an open question whether he has the financial resources to pay a large jury award. He might receive a lucrative book deal; he might not. Sometimes, a jury’s finding of liability is enough to validate a family’s feeling that their loved one has been unjustly taken away. But it may not be very satisfying in the absence of a criminal conviction.

So what can be done? In truth, not a whole lot. The state prosecution was the best opportunity to put Zimmerman behind bars. Federal charges are fraught with problems, and a wrongful-death suit might not give anyone a sense of closure. The president has encouraged Americans to seize this tragedy as an opportunity to discuss the intersection of race and law enforcement. But for distraught mothers like mine, discussion may do little to alter the reality that the law won’t always punish those who harm their sons.