Was Emily Dickinson a radical poet of the avant-garde, challenging the regularized notions of predominantly male poets and editors regarding stanza shape, typographical publication and distribution, spelling and punctuation, visual and verbal presentation, erotic love, and so on? Or was she a poet of restraint, who restricted herself to a few traditional patterns of meter and stanza, referred to the wayward Whitman as “disgraceful,” and wore her prim white dress as a sign of those renunciations best expressed in that wildest word “No”?

It is a conflict reaching back to what has come to be called “The War Between the Houses,” when Dickinson’s manuscripts were divided into two main collections. One consisted of the poems Dickinson had sent to her sister-in-law, Susan Dickinson. The other was the pile of manuscripts discovered in a drawer after Dickinson’s death in 1886 by her sister, Lavinia. Susan had first volunteered to find a publisher for Dickinson’s poetry. When in Lavinia’s view she showed insufficient zeal in pursuing this goal, Lavinia turned—in what seems a deliberate act of hostility—to Susan’s rival for her husband’s affections, Mabel Todd. Todd, more comfortable in the literary world, secured the cooperation of Dickinson’s literary adviser Thomas Wentworth Higginson as coeditor for the project.

The manuscripts sent to Susan were sold to Harvard in 1950. The others, in Mabel’s hands, were donated to Amherst in 1956. The spoils of Dickinson are also divided, with her bedroom furniture at Harvard instead of in the Homestead, which was deeded to Amherst. (As the Amherst archivist Michael Kelly recently told Jennifer Schuessler of The New York Times: “They have the furniture, we have the daguerreotype; they have the herbarium, we have the hair.”) With the resources of the Internet, it was hoped that the two collections might finally be united, at least “virtually.” And so Harvard (which has published successive versions of Dickinson’s collected poems and thereby retained the copyright) launched its “digital Dickinson” project. When the archive was about to go “live,” however, a spat broke out, reported in The Boston Globe and The New York Times.

It was learned that representatives of Amherst and Harvard—two historically men’s schools where Dickinson could never have enrolled—had differing ideas of what the archive should consist of and how it should be presented. Should it be free to all comers (the preference of Amherst, which had already made its manuscripts available online in 2012) or pay-per-view (Harvard’s preference)? Should it be identified with Harvard or should Amherst have equal billing? Should it be restricted, as Harvard preferred, to manuscripts identifiable with specific poems (namely, the 1,789 poems in Ralph Franklin’s three-volume variorum edition of 1998) or should it include all Dickinson’s manuscripts, incorporating those seemingly radical drafts and gnomic fragments (from the Amherst archive)?

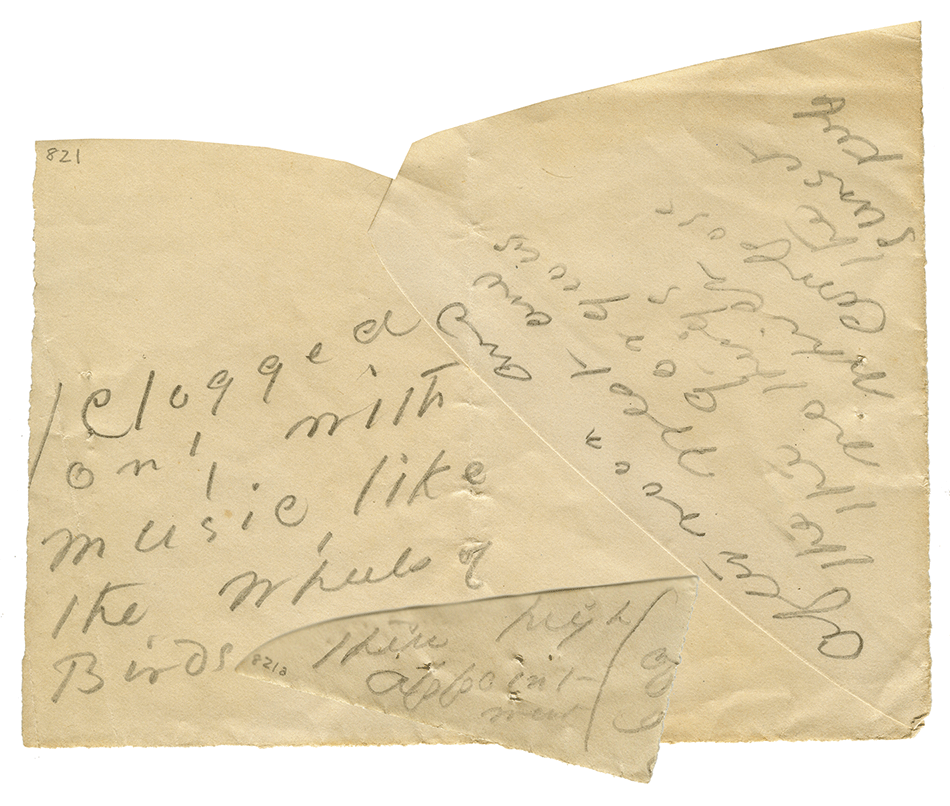

Perhaps the most extreme example is one of Dickinson’s “envelope poems” that the scholar Marta Werner describes as “a sudden collage made of two sections of envelope,” which resemble “the hinged wings” of a bird. On one section Dickinson has written, “Clogged/only with/Music, like/the Wheels of/Birds.” Another flap, written at an oblique angle to the first, reads: “Afternoon and/the West and/the gorgeous/nothings/which/compose/the/sunset/keep.” An additional small triangle, torn from the envelope and then pinned to the hinged sections, has the words “their high/Appoint/ment.” To give this odd concoction its full effect, Werner proposes an unfamiliar mode of reading and viewing:

To access the text(s), and to answer the question of where we have arrived, we must enter into a volitional relationship with the fragment, turning it point by point, like a compass or a pinwheel—like the wheels of thought. 360 degrees. As we rotate A 821 [the archival number from the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections], orienting and disorienting it at once, day and night—each a whir of words—almost collide in the missing spaces just beyond the light seams showing the bifurcation in the envelope, and then fly apart in a synesthesia of sight and sound.

Such an invitation will not appeal to skeptics, who are likely to insist that Dickinson was merely being a thrifty Yankee in her use of scraps for drafting poems, and that, like any poet scrawling the inspirations of a moment on whatever lies to hand, she intended eventually to resolve such seemingly bizarre verbal tangles in the familiar strictures of printed stanzas, familiar meters, and conventional line breaks.

Advertisement

Still, the new archive is now online, and the questions about what should go into it have mostly been resolved. It is by any measure an extraordinary resource, free to all, and allows readers to make up their own minds about how Dickinson’s manuscripts, with their alternative words, visual flourishes, enigmatic dashes, and indeterminate line breaks should be read or viewed. But for those convinced that Dickinson has been the victim, across several generations of scholars and “patriarchal” institutions, of a systematic effort to render her a conventional poet—morally restrained, heterosexual, a keeper of poetic as well as societal norms—the revolutionary work continues.

Meanwhile, those readers who wish to supplement the Harvard archive with more adventurous approaches can consult Werner’s own Radical Scatters website, or the extensive Dickinson Electronic Archives long maintained by the energetic scholar Martha Nell Smith, which include Werner’s updated analysis of the Lord fragments (“Ravished Slates”), discussions of a recently discovered 1859 daguerreotype that might possibly be the only known image of Dickinson as an adult, in the company of a woman who may have been her lover, and manuscripts of Dickinson family members, notably including poems and letters by Susan Dickinson, believed by Smith and other scholars to be the main love of Dickinson’s life.

One might think of these two scholarly tendencies, borrowing a distinction from anthropology, as embracing a “raw” versus a “cooked” Dickinson. What is clear is that Dickinson’s gnomic utterances continue to speak to artists and readers, perhaps with renewed urgency as our own relation to language shifts under the onslaught of the digital revolution. As we traffic increasingly in tweets and other abbreviated verbal messages, Dickinson’s own telegraphic art seems to issue from some other realm of authority, from the virtual “cloud,” perhaps, or from the night sky, scintillant with stardust.

Adapted from an essay that appears in the February 20, 2014 issue of The New York Review and which also discusses two New York exhibitions related to Emily Dickinson: “Janet Malcolm: The Emily Dickinson Series” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, which runs through February 8, and “Dickinson/Walser: Pencil Sketches,” at the Drawing Center, which closed on January 12.