Like Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali, David Lynch is a name-brand artist who confounds conventional categories. Lynch was the first American avant-garde filmmaker to direct a Hollywood blockbuster (the ill-fated Dune, 1984), the first to create a prime-time network TV show (the fabulously idiosyncratic Twin Peaks, 1990), the first to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes (Wild at Heart, 1990), the first to open a Paris nightclub (the ultra-finished sub-basement Silencio), and the first, save Warhol or Bruce Conner, to have a museum retrospective of his paintings, drawings, prints and assemblages.

Is Lynch a celebrity painter? Or, put another way: Would the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) be exhibiting four decades of his work, were he not 1) a world-famous movie director and 2) the most famous PAFA alum since Mad magazine cartoonist Don Martin or Thomas Eakins or maybe ever? Impossible to answer and pretty much irrelevant, as Lynch’s paintings and assemblages place his movies—or at least the great ones, Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire—in the setting of his art work and not vice versa.

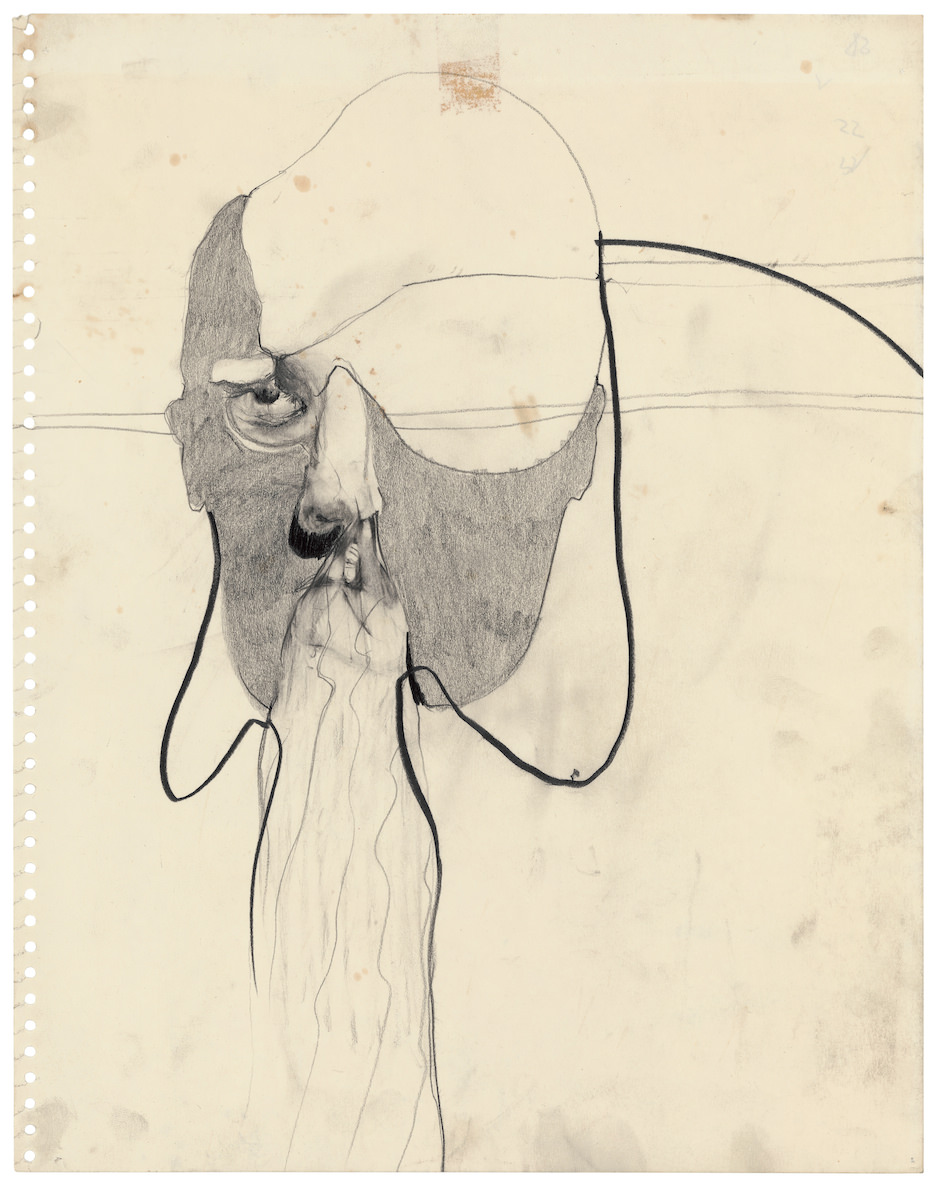

The first image glimpsed beyond the portal to “David Lynch: The Unified Field” might be a riff on one of Jasper Johns’s late 1960s single-image relief paintings—a human face at the center of a dark grey field, supported, as if a flower, by a stringy-looking white stalk. Entering the room you discover it’s the 1967 canvas Man Throwing Up. Welcome to Lynchland, where bodily fluids and organic matter are the coin of the realm, orifices gape, revulsion merges with delicacy, and austerity is the handmaiden of disgust.

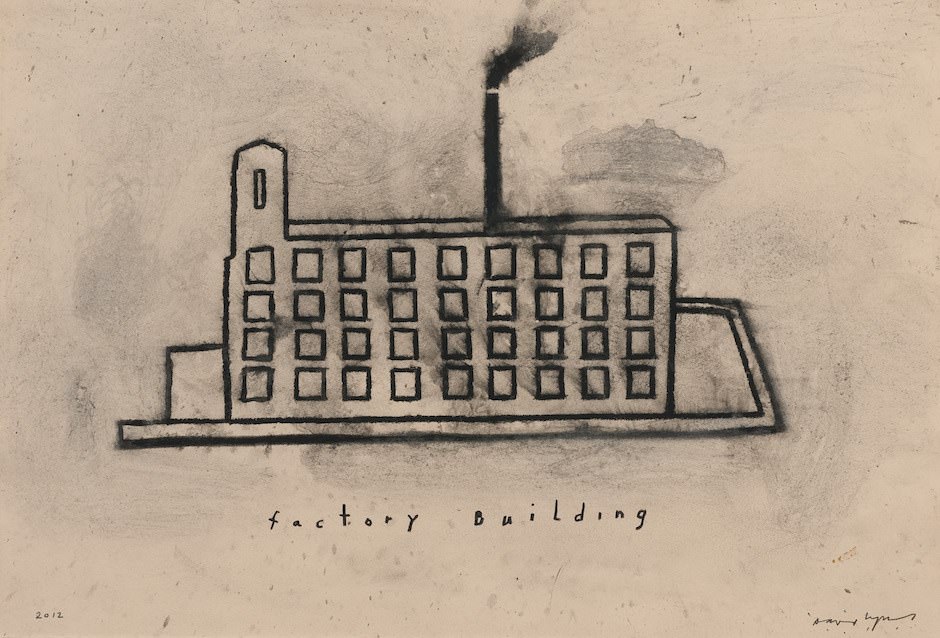

After studying for a few semesters at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Lynch enrolled at PAFA in January 1966. By his own account, proudly displayed on “Unified Field” signage, he found Philadelphia, then in a state of urban decay, to be a revelation. The city had “a great mood—factories, smoke, railroads, diners, the strangest characters and the darkest night… I saw vivid images—plastic curtains held together with Band-Aids, rags stuffed in broken windows.”

Lynch’s student work includes a number of meticulous, soot-colored drawings of twisted organs and tortured torsos, reminiscent of the surrealist doll-maker Hans Bellmer, and, even more, Lynch’s then idol, Francis Bacon. Lynch’s most celebrated piece, Six Men Getting Sick (1967) is a study in abstract projectile vomiting, with an animated film loop projected on a shaped canvas, accompanied by the sound of a police siren. Dropping out of PAFA in mid-1967, the artist remained in Philadelphia, painting and making short films, for another three years; he relocated to Los Angeles after receiving an AFI fellowship to work on the feature project that would eventually become Eraserhead, a movie Lynch would always associate with his life in Philadelphia.

As befits an exhibit held in an academy, “The Unified Field” makes two pedagogical points. First, the show demonstrates that, placed in relation to Lynch’s oeuvre, Eraserhead was the last great underground movie, albeit one that (as precursor films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol never did) improbably led to the artist having a Hollywood career informed by his art-world ideas and interests. The second point is that Lynch never gave up painting.

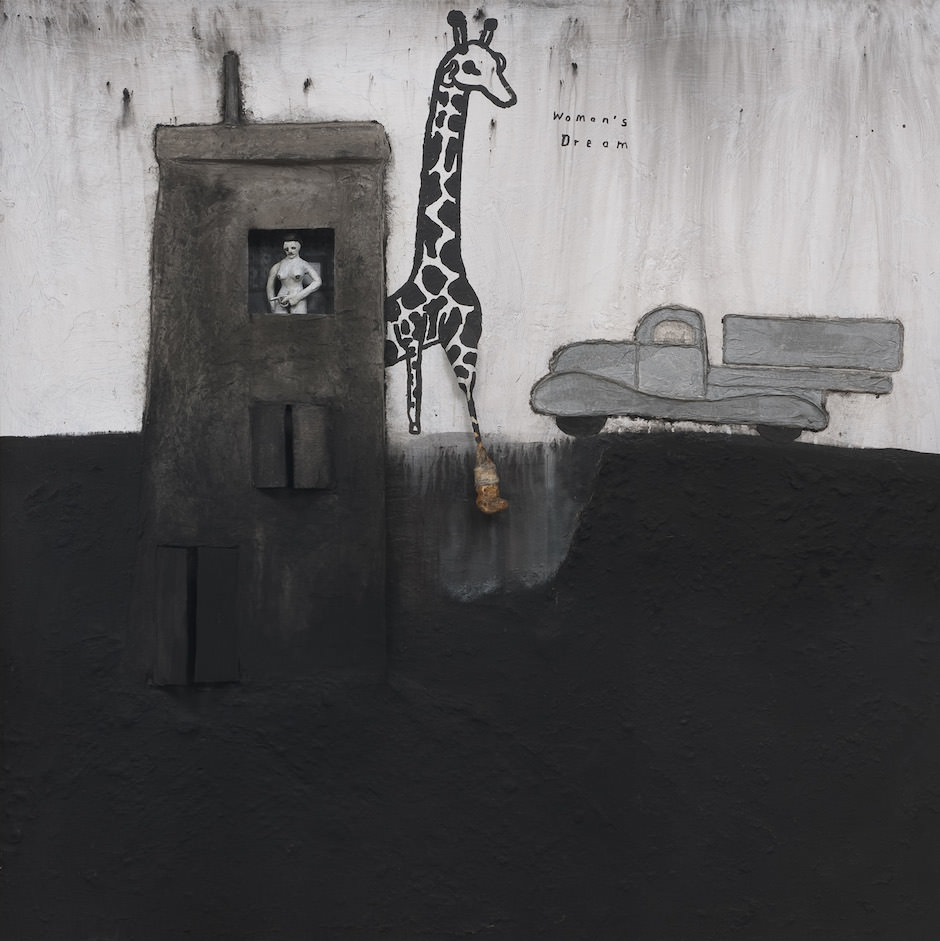

Lynch’s last Philadelphia canvases are brutally textural, integrating cigarette butts and filters, matted horse-hair, and bits of unidentifiable petrified organic matter. His more recent work, characterized by broad paint strokes and large-scale dramatic canvases, is more polished in its perversity. These paintings could be more accurately described as assemblages. Mister Redman (2000) employs dice, matchsticks, bandaids, epoxy, distressed fabrics, chicken feet, and lumps of oil paint. Lynch favors an austere, monochromatic palette but some canvases, like Mister Redman or the violently creepy Rock with Seven Eyes (1996), a black tumor or turd studded with glass orbs, make use of a distinctly bilious orange.

Although part of an American gothic tradition including such masters of textural yuck as the painter Ivan Albright and the assemblagist Ed Keinholz, as well as the more refined Edward Gorey, Lynch’s images, with their heavy lines and thick impasto, are far cruder. Lynch has long been the American director with the most direct pipeline to his unconscious—his graphic work suggests the doodles of an extravagantly disturbed child, the inscribed captions (“There is nothing here, please go away” or “Change the fucking channel, fuckface”) seem phrases he might have heard or imagined as a boy.

The implied or explicit subject of these paintings is often arson, rape, or murder, but in Lynch’s work, merely existing is a violent affair. The 2009 painting Man with Thought has an amorphous humanoid with a chalk-outlined hand stuck in his mouth, exuding a blue blob from one side of his head and a more textured disc from the other. The recent canvas I Am Running Home From Your House (2013) has a child-like image of a boy in full flight, racing downhill from a distant red structure. An asteroid or dirt clod above his head is labeled “bad thoughts.” The materialization of those thoughts is what Lynch’s art is all about.

Advertisement

“David Lynch: The Unified Field” is on view at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through January 11.