I usually have no patience for “happy family” literature, not to mention the contemporary habit of adults reading mediocre books for “young adults,” whoever they might be. But to my surprise, Astrid Lindgren’s Seacrow Island (1964), an idyll about a family and a village set in the Stockholm archipelago in the mid-twentieth century, has enchanted me. When I read it for the first time this spring (it has just been brought back into print by The New York Review Children’s Collection), I liked it so much that I consumed it slowly, like a savored cake. A month later I read it again, perhaps even more deliberately. It is a beautiful book, rendered in an entirely fluent English translation by Evelyn Ramsden, and certainly for adult readers as well as the children to whom it could be read.

One of the text’s many pleasures is its quicksilver pivoting among points of view: from omniscient to close third persons (many of them) to the first-person text of one character’s diary. Lindgren handles all this as deftly, as if there were no trick to it at all. Consider this passage, about a young boy (Pelle) who is often anxious, and whose anxiety begins to focus on the end of the family’s summer on the island:

Pelle had already begun to dread the awful day when they would all have to go back to town. He had an old comb with as many teeth as the summer had days. Every morning he broke off a tooth and noticed anxiously how the comb grew thinner and thinner.

Melker [his father] saw the comb one morning and threw it away. To worry about the future was the wrong attitude toward life, he said. One should enjoy each day as it came. On a sunny morning like the present one, life was nothing but happiness. How wonderful it was to go straight out into the garden in pajamas, feeling the dew-wet grass under one’s feet, and then take a dip from the jetty and afterward sit down at the painted garden table to read a book or the paper while drinking delicious coffee, with the children milling around!

Best known for having created the red-headed and wildly independent little girl Pippi Longstocking, Astrid Lindgren (1907-2002) is to her native Sweden some combination of George Washington and a patron saint; last year the Bank of Sweden put her image on the twenty-kronor note. In Sweden, she is famous for all of her books for children, around fifty titles, many appearing in series format, many not involving Pippi. On the Web, you can find a site that shows pictures of the apartment in Stockholm where Lindgren lived and worked; you can also find the “Astrid Lindgren’s World” theme park (more dinky-town than Disney) set in her childhood farming village of Vimmerby, Småland. Here a young woman with Pippi-braids and freckles romps about, and rather alarming wax figures inhabit diminutive storybook houses from Lindgren’s tales—such as The Children of Noisy Village books (also called The Bullerby Children books, written between 1960 and 1987), Karlsson on the Roof (three books, written between 1955 and 1968), and the Emil of Lönneberga series (1963 to 1997). There is, alas, also a waxen family Melkerson in their Carpenter’s Cottage on Seacrow Island.

But none of this fond kitsch can take away the intensity of the stories—often very funny, and sometimes melancholy and sometimes very dark—that Lindgren told. In Vivi Edström’s Astrid Lindgren: A Critical Study, I learned that there is a manuscript scholars call the “Ur-Pippi,” the first draft of the Pippi Longstocking stories that Lindgren, then a young mother, wrote in the 1940s. The original Pippi was more truly a classic trickster than the one we know now: unapologetic and profane—and possibly, or so Edström says, meant to be a “child of nature” figure. In order to tame that Pippi slightly for public consumption, Lindgren’s publisher persuaded her to tone the story down in a few places.

For example, Pippi actually apologizes to the schoolteacher she has defied and does not, in her madcap rescue of children from a burning building, accidentally-on-purpose smash a chamber pot (as she did in the draft). But despite Edström’s cataloging of differences, I am struck by how much of the Ur-Pippi remains—outwitting thieves, sleeping with her feet on the pillow, using her super-human strength to carry a horse or a policeman in her arms, and defying all conventions of proper speech with her brags, lies, and wisecracks. Parentless (her mother is dead; her sailor father is away at sea, where he is, among other things, “king of the cannibals” on a distant south-seas island), Pippi lives with a monkey and a horse next door to ordinary Tommy and Annika, in a town that somehow manages to accommodate Pippi’s outsize personality, her refusal to attend school, and her eagerness for mayhem.

Advertisement

When Pippi visits the circus, she gets in the ring herself, first by jumping on with the bareback rider, then on the tightrope: “She stretched one leg straight up in the air, and her big shoe spread out like a roof over her head. She bent her foot a little so that she could tickle herself with it back of her ear.” The ringmaster’s security guards are unable to remove Pippi because she is too strong for them; and she finishes her circus debut by taking up a wrestling challenge:

“Now, little fellow,” said she, “I don’t think we’ll bother about this any more. We’ll never have more fun than we’ve had already.”

Mighty Adolf stole out as fast as he could, and the ringmaster had to go up and hand Pippi the hundred dollars, although he looked as if he’d much prefer to eat her.

“That thing!” said Pippi scornfully. “What would I want with that old piece of paper. Take it and use it to fry a herring on if you want to.” And she went back to her seat.

The New York Review Children's Collection

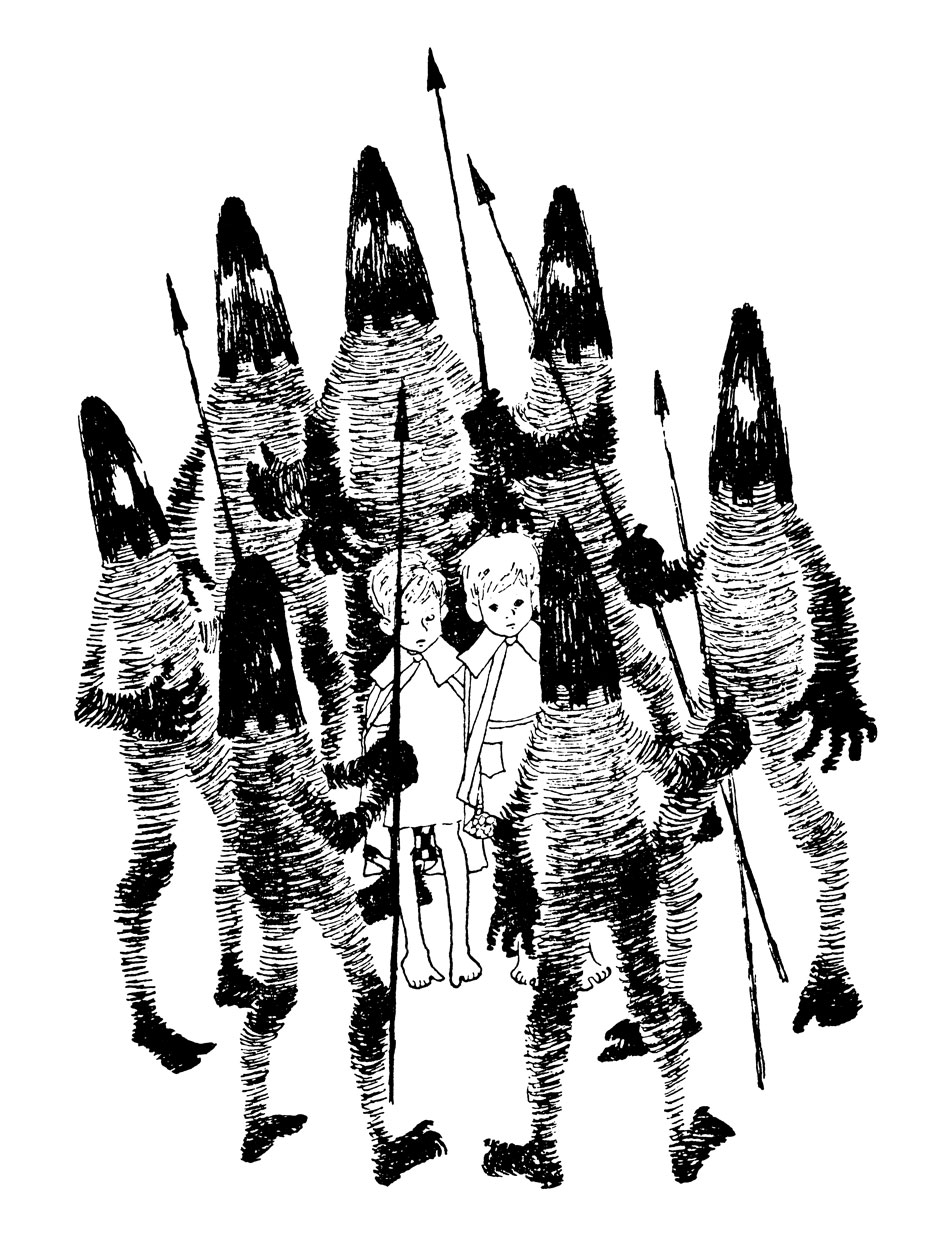

An illustration by Ilon Wikland from Astrid Lindgren’s Mio, My Son

My befuddlement at the strange and misshapen story of Mio, My Son was cleared up by learning, again from the helpful critic Edström, that Lindgren had originally written and published (in a magazine) what is now the first chapter as a self-contained short story. It is a “weird tale” that begins with the narrator explaining that the police bulletin about a disappeared child—“a nine-year-old boy [is] missing from his home…. At the time of his disappearance he was wearing brown shorts, a gray sweater, and a small red cap”—is a description of himself, an orphan. “I am Karl Anders Nilsson.” He then proceeds to tell about how he was not loved by his adoptive parents, how he envied the warmth of his friend Ben’s home (especially the love of Ben’s father), and how one day, sitting alone on a park bench at dusk, he received a magic sign and found a genie in a beer bottle, who took him to his “real father,” in “Farawayland.” There he meets his father, the King (who looks a lot like Ben’s father, only even better) and is greeted as “Mio, my son,” by this man. The story ends:

I’d like Ben to know about all the remarkable things that have happened to me here. He could call the police too, and tell them that Karl Anders Nilsson, whose real name is Mio, is safe in Farawayland and all is fine, so fine with his father the King.

Once this story was published, apparently Lindgren was besieged by letters from children, asking for more stories of Mio in Farawayland. So she wrote more, and a mish-mash of fantasy adventures was the result. I do not imagine that many adults asked for more, however, since to the adult reader it is pretty clear that Karl is dead, like most children who go missing, and that he is narrating his story from beyond the grave, Sunset Boulevard-style.

In the utterly different world of Seacrow Island—a world one would say was almost the opposite of noir—lives another such self-possessed child, this one a thriving, willful girl with her own magical quality. She is Tjorven, and Malin (the oldest daughter of the Melkerson family, who has just arrived for the summer) sees her alongside her St. Bernard dog on the dock as they arrive:

This person was female and about seven years old. She stood absolutely still as if she had grown up out of the quay. The rain poured down on her but she did not move. It seemed almost as if God had made her as part of the island, thought Malin, and had put her there to be the ruler and guardian of the island to all eternity.

The presence of nineteen-year-old Malin—given to flights of diary-writing fancy and a number of young romances—as one of the story’s chief chroniclers allows Lindgren to step a toe into sentimentality now and then without the whole novel going soppy. After all, that’s how nineteen-year-old girls think and write; and Lindgren herself said more than once that one of her chief literary influences as a writer was the (almost unbearably sweet) Anne of Green Gables. Malin is tougher and realer than Anne, however; and Tjorven is, in her own way, even tougher than Pippi Longstocking. She is funny, and blunt, and queen-like, always attended by her loyal dog. Although her mother occasionally intervenes to change her wet clothes or to send her to bed, she does so with the apparent knowledge that her daughter is only humoring her by obedience. In a world where the Melkerson children (Malin, Pelle, Johan, and Niklas) protect their very weak father, Melker, Tjorven befriends him as an equal:

Tjorven faced Melker with more bitter truths than anyone else, and he sometimes gasped and was just about to scold her when he realized that it would be entirely useless. She was what she was and said what she thought.

Trying to convey charm, as a quality of a text, turns out to be ludicrously difficult. When I tell you that the Melkerson children are always making allowances for their head-in-the-clouds, self-pitying, impossible father, you will of course be inclined to tsk-tsk over this dysfunctional family. All the more so, when I add that Malin plays the role of mother to all her brothers and her father, and that they all interfere with her romantic prospects because they fear losing her. And yet the dysfunctions are not rigid; the father manages to do his job as a father from time to time, and Tjorven shows up to tell him off when required. The brothers love their sister enough to begin to imagine letting her go. So it is as if the quality of freedom that the family finds by summering on Seacrow—pumping water, fetching milk from the cows on the other side of the island, fostering pets (which include a rabbit, a seal, dogs, a lamb, and a hive of wasps), spending days exploring and playing with other children on the water and in the fields and woods—frees them from the troubles they knew in their life in Stockholm. Despite storms, getting lost in a fog, almost losing their cottage, and other such dramas, this is a sort of fairy-tale, a tale of redemption and therapy: the family is healed by nature, and by living in the “old ways.”

It turns out that German readers have especially loved the “old ways” antics of the six Bullerby children in The Children of Noisy Village. These stories are set in the pre-war 1930s, in the district of Nås, not far from where Lindgren grew up, and a nostalgia for lost innocence is a part of their appeal. Lindgren’s stories are of course widely translated—in fact, she is the third most-translated children’s author, after the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, with 144 million books sold worldwide. So it is not too surprising that, in Germany, a term has come into use—Bullerbü-Syndrom or “Bullerby Syndrome,” referring to a nostalgia for Nordic culture, with blond children, Midsummer festivals, and the like. That this also, of course, paradoxically resembles the nostalgia invoked by the Third Reich is a complication I leave to specialists.

Astrid Lindgren’s Seacrow Island, translated by Evelyn Ramsden, and Mio, My Son, translated by Jill Morgan, have just been reissued by The New York Review Children’s Collection.