In this summer of shipwrecked refugees and the Greek debt crisis, what could possibly shake institutional Europe back to its senses about our common humanity? The sight of wide-eyed children huddled together on leaky life rafts, after an infernal journey across the Sahara? An elderly Greek man sunk to the ground in front of a half-closed bank in Salonica, weeping from fear and frustration? If only these desperately lost souls knew what a powerful defender they have in an ancient poet of Athens: Aeschylus, nicknamed “the Sicilian,” author of the oldest theatrical works to survive to the present day.

The most archaic of Aeschylus’s plays, at least in its form, is a tragedy called The Suppliants, produced sometime after 470 BC in Athens. The play is regarded as archaic because so much of its action is reserved for a chorus of twenty-four people singing, acting, and dancing as one. But this ancient form works perfectly to tell the tale of the fifty daughters of the Egyptian king Danaus, who escaped from Africa to Greece together with their father in order to avoid having to marry their fifty cousins. In theory, the ancient Greeks granted rights of asylum to anyone who took refuge in a temple or sacred precinct and called upon the gods for protection. In practice, suppliants had to be officially accepted as such for the divine safety net to work; that moment of doubt for the daughters of Danaus, newly landed on the beach near the Greek city of Argos, provides Aeschylus with the initial suspense for his play.

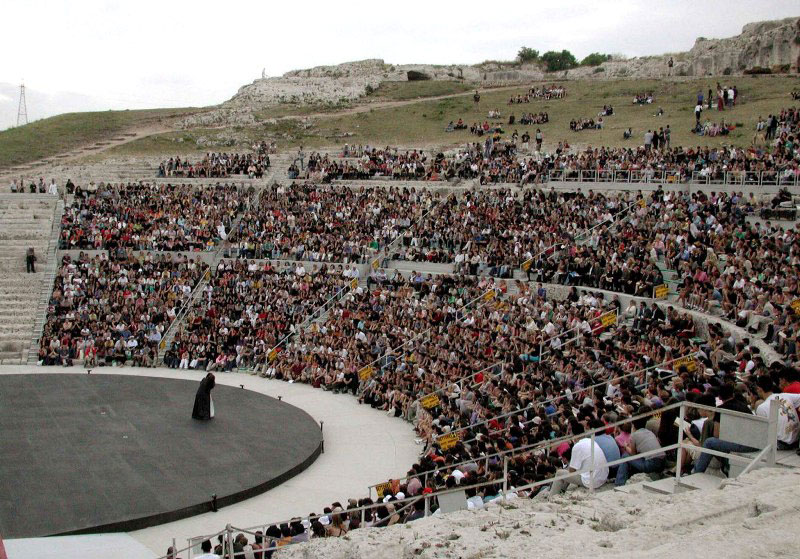

A similar process of triage is now taking place every day in refugee centers on the shores of Italy, tiny Malta, and Greece—even as they face a crushing burden of debt to the European Central Bank, the Greeks are also receiving a huge proportion of the refugees fleeing the bloodbaths of the Middle East, the refugees that much of the rest of Europe is reluctant to admit. The geographical location of the Greek peninsula has certainly contributed to the onslaught, but so has the immemorial tradition of hospitality that plays a central part in The Suppliants. Greeks should not refuse a stranger. And thus this summer, in the ancient Greek theater of Syracuse in Sicily, one of the world’s most ancient plays turned out to be one of the world’s most timely, in the hands of an Italian actor-director who was once an immigrant himself, Moni Ovadia. (His family moved from Bulgaria to Milan in 1946, when he was a young boy.)

Indeed, in staging The Suppliants in present-day Sicily, the director’s real aim was to enter straight into some of the most urgent concerns of contemporary life. In today’s Syracuse, where African refugees beg at traffic lights, he reserved a whole block of seats in the theater for refugee groups to watch the performance; however inaccessible the spoken dialogue might have been, music, dance, and gesture underlined the story at every step. With the help of translator Guido Paduano (who rendered the ancient Greek original into a crystalline Italian) and Sicilian minstrel Mario Incudine, Ovadia set the text of Aeschylus into a poetic combination of Sicilian dialect and modern Greek, guessing, correctly, that most Italians are so familiar with the work of the Sicilian writer Andrea Camilleri that they have already absorbed a good deal of Sicilian into their working vocabularies.

Not coincidentally, Sicilian dialect and Modern Greek are also the two languages refugees are most likely to hear when they arrive in Europe, and it is always a marvelous thing to hear Greek as a living language spoken in a theater built by Greeks so many centuries ago (in its present form, the theater of Syracuse dates from the third century BC, but Aeschylus himself produced plays in a fifth-century predecessor). Incudine, dressed as a traditional Sicilian cantastorie, a minstrel, set the story in a larger mythological context at the beginning and the end, finishing with the words: “But I’m just a poet named Aeschylus, called ‘the Sicilian.’” Pandemonium.

It takes a special kind of director to reveal the titanic stature of Aeschylus, the most intensely, rousingly political of all the Greek tragedians, a show-stopper of a dramatist with an uncanny ear for the ringing line that will bring an audience to its feet. (“Sons of Greece, arise, free your homeland, free your children, your wives, the temples of your ancestral gods, the tombs of your forebears—the fight now is for everything,” the messenger says in The Persians, his earliest surviving play, about the Battle of Salamis.) Yet for all his demagogic skills, Aeschylus is no warmonger. He had faced the Persian army as an Athenian hoplite on the plain of Marathon in 490 BC, but he presents his onetime adversaries in The Persians as fellow human beings, not barbarians from another world. His most chilling words about armed combat come from Agamemnon, where the chorus calls Ares, the god of war, “the moneychanger of bodies.” Aeschylus was a man of lofty ideals, but he had sharp eyes.

Advertisement

This was the writer, and the legacy, that Moni Ovadia took on this summer in Syracuse, with results that critic Gianni Bonina described as “[entering] the great repertory of European theater.” Greek drama, with its open-air setting, calls for loud voices and outsized gestures; poetry transforms the shouting into oratory and dance lends the gestures a stylized grace. Syracuse is a magical place to do this. The theater rises next to a quarry with a curving cave that Caravaggio, who visited in 1608, compared to an ear because of its uncanny reverberation. In Ovadia’s production, a four-piece bouzouki band provided the virtually nonstop music for this seventy-minute drama, backed on occasion, dramatically, by a gigantic drum.

The chorus entered clad in burkas, changing to wild African-inspired costumes with jungle prints, body painting, hip-length dreadlocks, and bare plastic breasts; the chorus leader, Sicilian actress Donatella Finocchiaro, as majestic in her bearing as Atossa in The Persians. (Aeschylus, unlike many of his fellow Athenians, saw women as human beings, too.) When the Greeks first see the refugees, they are dressed in the anti-Ebola suits that rescue workers are often wearing when they pick up boat people in the Mediterranean, while their king Pelasgos, played by Ovadia, gravel-voiced and physically imposing, is dressed in an amazing Aegean-blue robe with a Doric column up its front and an Ionic temple on its back. In a sung exchange that keys up higher and higher, the suppliants and their father make their case for asylum, gradually persuading gruff Pelasgos and his subjects—who, he insists, are the real rulers of the state, a line that must have drawn ecstatic applause in the 460s BC and still does.

All seems to be well, when suddenly the maidens’ Egyptian cousins appear on the scene, dressed in linen skirts worthy of King Tut, but goose-stepping in jackboots, their Germanic helmets topped by Egyptian fans. They are egged on by a leering general who bumps and grinds atop what looks almost like a gigantic Trojan horse, but is really a sky-high four-horse chariot. It is pure melodrama, but it works as brilliantly now as it did two and a half millennia ago. As the villains drag their prey away in a giant net, the Greeks come out in force, and Pelasgos delivers a ringing speech in modern Greek, repeating his last command in pungent Sicilian: Vattini! “Get out of here!”

They retreat, the audience cheers. Then Pelasgos turns to the Danaids and Danaos: “You’re free! You’re free in this city, and I, with my sovereign people, are the guarantors of your freedom.” (Liberi siti ormai nta sta città, iu e lu me populu suvranu semu ‘i garanti di la vostra libertà.) More cheers. “We are a hospitable people.” More cheers. “Come into the city. Our houses are yours, and not the smallest ones. You are free to choose.” It is a typical Aeschylean ending, an ecstatic party to celebrate the creation, from danger and misery, of civil society. But the young minstrel Mario Incudine comes in to tell us what happened next, how the Egyptian cousins returned and forced the girls into marriage, how forty-nine of them murdered their husbands on their wedding night, how the one who fell in love with her husband and spared him, Hypermnestra, went on to found a dynasty, while her sisters were condemned in Hades to carry water in sieves. “But what do I know? I’m only a poet, named Aeschylus, called ‘the Sicilian.’”

What lesson do we suppose we can teach these people by forcing an elderly Greek man to collapse to the ground and weep because “Europe” is unwilling to find some different way to get him his pension or relieve his suffering? What is this continent about? What is its greater contribution to humanity at large: Greek theater or double-entry bookkeeping? Aeschylus or Keynes? What does Europe want to say for itself? Liberi!, or “In the name of God and of profit”?