Rarely does a newspaper story get the kind of response that The New York Times front-page exposé of wage-theft at nail salons prompted this spring. Profiling at length the experiences of a woman named Jing Ren—a twenty-year-old recent immigrant who was paid no salary for her first three months on the job and was shockingly underpaid after that—the nearly 7,000-word article asserted that “rampant exploitation” afflicts “a vast majority” of the many thousands of manicurists in the more than 3,600 nail salons of New York State. The article said it drew on interviews with more than one hundred salon workers, nearly all of whom “had wages withheld in ways that would be considered illegal.” It also suggested that these practices have been systematically ignored by city and state authorities.

Within hours of the story’s publication on May 10, Governor Andrew Cuomo ordered a multi-agency task force to investigate all New York salons for alleged mistreatment of workers, and then he signed a new law that, among other things, makes it a crime to operate a salon without a license. Just as quickly, the Internet lit up with expressions of indignation and alarm, reflecting a sudden alteration of the collective conscience. The writer of the Times story, Sarah Maslin Nir, who covers Queens for the paper, said in an interview on the Times website, “Your discount manicure is on the back of the person giving it”; a blog on the website of The Christian Science Monitor used the term “salon ‘slaves’” to sum up her story. A few weeks after the exposé came out, Dean Baquet, the Times’s executive editor, hailed it as a model “investigative story with impact.”

But was it true?

As a former New York Times journalist who also has been, for the last twelve years, a part owner of two day-spas in Manhattan, I read the exposé with particular interest. (A second part of the same investigation, which appeared in the Times a day later, concerned chemicals used in the salon industry that might be harmful to workers.) Our two modestly-sized establishments are operated by my wife, Zhongmei Li, and my sister-in-law, Zhongqin Li, both originally from China, and “mani-pedi” is a big part of the business. We were startled by the Times article’s Dickensian portrait of an industry in which workers “spend their days holding hands with women of unimaginable affluence,” and retire at night to “flophouses packed with bunk beds, or in fetid apartments shared by as many as a dozen strangers.” Its conclusion was not just that some salons or even many salons steal wages from their workers but that virtually all of them do. “Step into the prim confines of almost any salon and workers paid astonishingly low wages can be readily found,” the story asserts. This depiction of the business didn’t correspond with what we have experienced over the past twelve years. But far more troubling, as we discovered when we began to look into the story’s claims and check its sources, was the flimsy and sometimes wholly inaccurate information on which those sweeping conclusions were based.

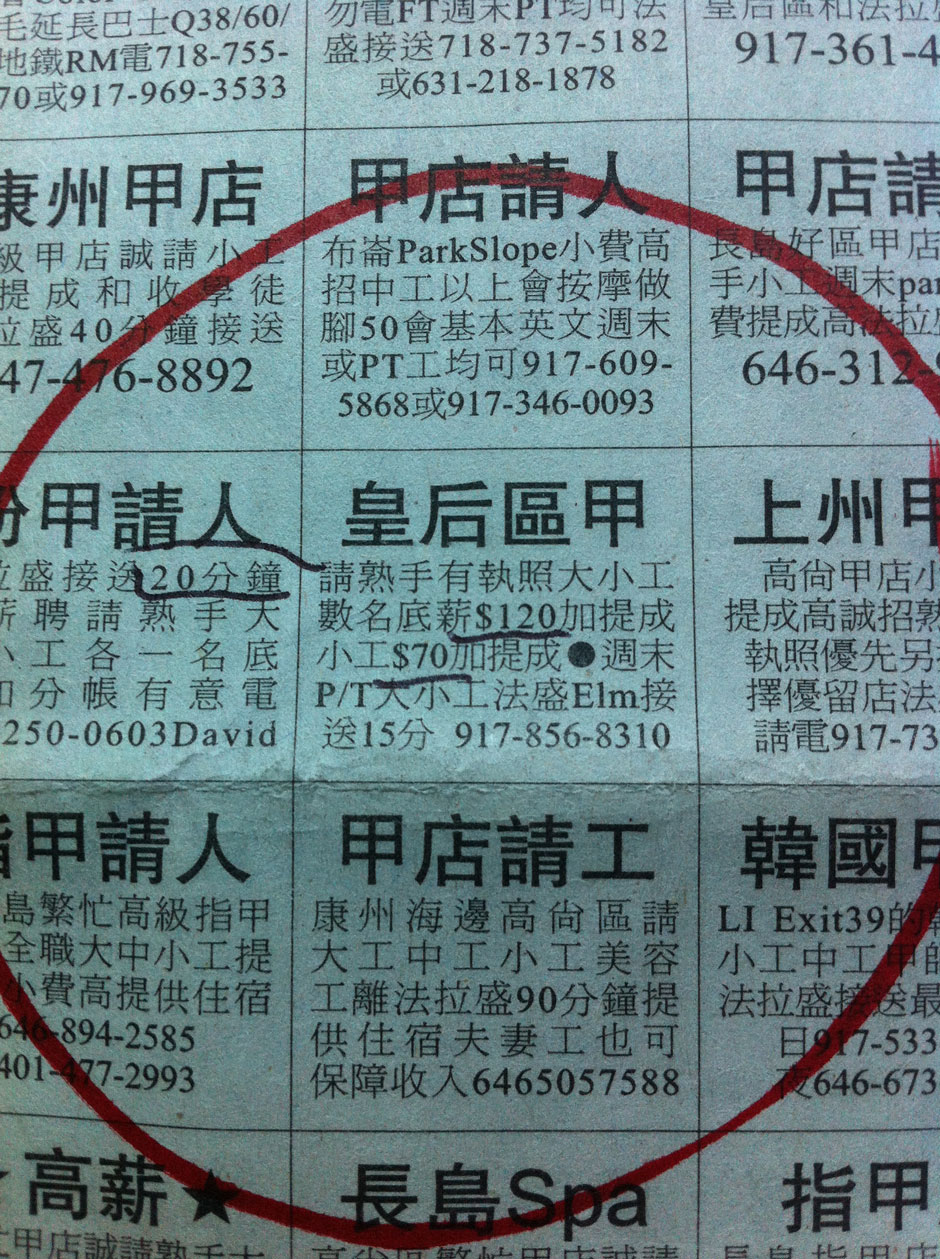

Consider one of the article’s primary pieces of evidence of “rampant exploitation”: in a linchpin paragraph near the beginning of the article, the Times asserts that “Asian-language newspapers are rife with classified ads listing manicurist jobs paying so little the daily wage can at first glance appear to be a typo.” The single example mentioned is an ad by a salon on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, which, according to the Times, was published in Sing Tao Daily and World Journal, the two big Chinese-language papers in New York, and listed salaries of $10 a day. “The rate was confirmed by several workers,” the story says. Judging from readers’ comments on the Internet, this assertion was a kind of clincher, a crystallization of the story’s alarming message.

And yet, it seems strange, or it should have seemed strange to the paper’s editors, that the sole example the reporter provides of the sort of ad that the Asian-language papers are “rife with” is one that is not even quoted from and for which no date is provided. Indeed, it’s not clear whether the reporter saw the ad at all—otherwise why the caveat “The rate was confirmed by several workers”? (Curiously, while Ms. Nir appears to have visited the salon in question, the story doesn’t say whether the owner of the salon confirmed or denied placing such an ad—or whether that question was even asked.)

To test the Times’s assertion, my wife and I read every ad placed by nail salons in the papers cited in the article, Sing Tao Daily and World Journal. Among the roughly 220 ads posted in each paper in the days after the Times story appeared, none mentioned salaries even remotely close to the ad the Times described. This led me to wonder if embarrassed salon owners might have changed their ads in the short time since the Times exposed them, so we looked at issues of World Journal going back to March this year. We read literally thousands of Chinese-language ads, and we found not a single one fitting the description of the ads that the Times asserts the papers to be full of.

Advertisement

In fact, only a small number of the nail salon ads indicate a salary at all—most simply describe the job on offer and provide a phone number for an applicant to call. Among the few ads that do indicate a salary, the lowest we saw was $70 a day, and some ranged up to $110. Here is one typical example, which appeared in the World Journal on April 23, several weeks before the Times article was published:

QUEENS AREA NAILS

Seeking several large and small work experienced hands.

Base pay $120 plus tips and commissions.

Small work $70, plus tips and commissions.

Seeking part-time small and large work on weekends.

15 minutes two-way transport Flushing to Elmhurst provided.

The “base pay” in this ad indicates what is known in the business as “large work” salaries—for workers licensed to perform jobs like massage or facial treatments. The “small work” salaries are for manicurists. In our experience, tips and commissions (a percentage of the price for add-on services like massage or special nail finishes) would add between $25 and $50 a day to these figures. A few ads we came across offer higher rates. For example, an ad placed in June by a salon on King’s Highway in Brooklyn was labeled “URGENT,” and offered jobs at starting salaries of $110 to $130 a day. To attract workers, many ads, like the April 23 one quoted above, promise to provide free transportation from the sort of pickup places where the Times reporter first encountered Ms. Ren, with the ad indicating how long the ride will be. Another ad posted in World Journal that day, for example, says, “Long Island spa needs small work high pay full and part time, 20 minutes pickup from Flushing.”

But could it be that the ads indicating salary were not representative? Since most ads do not specify compensation, my wife called a few of the advertising salons at random, speaking Chinese, posing as a salon worker, and asking what the pay would be. The lowest salary she was cited was $70 a day, but the woman she spoke to, who allowed that that salary was “low,” quickly added that tips and commissions were “very good” at her salon, which she said was in Upper Manhattan. This conformed to the practice at our own two salons, where we offer starting salaries of $70 a day, plus tips and commissions. My wife has learned that if she is unable to assure her employees that they will earn a total of at least $100 a day, nobody will work for her. On busy days the take home pay can be $150 or more. Of course, even $150 a day does not constitute great wealth. Nonetheless, the classified ads, clearly and unambiguously, reveal the opposite of what the Times claims they do. They show that there is a lively demand on the part of nail salon owners for qualified workers and that the salons need to pay them at least minimum-wage rates to start, plus, in many cases, provide free transportation to and from pickup places in the Flushing Chinatown, to induce them to take the posts on offer.

Needless to say, it is not like The New York Times to get things so demonstrably wrong, or, if it did make a mistake, to show no willingness to correct it. As a former reporter at the paper familiar with its usual close editorial scrutiny of its contents, I was genuinely mystified by this matter of the classified ads, and I wanted to see if there was some explanation for them. And so, two days after part one of the Times exposé appeared, I emailed several senior Times editors, including Mr. Baquet, as well as Margaret Sullivan, the Times’s public editor, who represents readers’ interests vis-a-vis the editors, pointing out what appeared to be the paper’s misrepresentation of the ads. I received cordial replies from editors, but my questions about the ads were ignored, except by Ms. Sullivan who, in an email, told me she had asked Wendell Jamieson, the editor of the paper’s Metro Section, about them. Mr. Jamieson told her he had “direct knowledge” of the ads and was satisfied that they had been accurately described. I replied to Ms. Sullivan that I didn’t know what Mr. Jamieson meant by “direct knowledge.” Ms. Sullivan wrote again, saying that she had had a chance to “clarify” what Mr. Jamieson meant by that term: “that he has reviewed the newspaper ads over the past few days, and he is confident that they were represented accurately in the story.”

Advertisement

But these were the very “past few days” during which my wife and I, both of whom can read Chinese, were examining the ads, and the Times description of them was unarguably, incontrovertibly wrong. The Times has neither furnished any copy of the ten-dollar-a-day ad in question, nor identified when it appeared. But even if such an ad did actually appear at some point, the unanswered question would remain: why did the Times reporter, in seeking to portray the whole industry, fail to describe or even mention the numerous, very different kinds of nail salon ads that are easily visible in any of the main Asian-language papers every day? The Times, moreover, seemed curiously incurious about another obvious question: given that there are numerous ads listing salaries of $70 to $110 a day—and salons quoting similar figures when contacted by phone—why would any job seeker answer an ad offering one-seventh or one-eleventh of that amount?

The discussion of Chinese-language ads was only one of many ways the Times article made data conform to a predetermined shape. For example, the story reports that Ms. Ren had to pay $100 “in carefully folded bills” to a Long Island salon owner on her first day. According to the paper, this “deal”—paying a fee to get a job that may pay no salary at all initially—“was the same as it is for beginning manicurists in almost any salon in the New York area.” The paper presents no evidence whatsoever to support this broad and damning conclusion. For what it’s worth, in our twelve years in this business, we’ve never entered into such a “deal,” nor have we heard of such a thing.

The Times story says that government inspections of nail salons are so infrequent as to be effectively non-existent, a failure that enables salon owners to operate unlicensed businesses with impunity; according to the Times, when inspections have occurred, in a “vast majority” of cases they only happened after workers complained to the state. I guess we are unlucky, because at least once, often twice a year, inspectors have come unannounced into our salons, unprompted by any complaints, to verify our employees’ licenses, which, as required by law, are posted on a wall. According to figures provided to me by the New York Department of State, between May 2014 and May this year, there were 5,174 inspections of “appearance enhancement” businesses, which would include ordinary beauty as well as nail salons. Seventy-eight businesses, or about 1.5 percent of those inspected, were fined for operating without proper licenses.

Ms. Nir makes a point of telling readers that among the 115 statewide investigators, only eighteen speak Spanish, eight Chinese, and two Korean—even though these languages are “essential tools for questioning immigrant workers to uncover whether they are being exploited.” But Ms. Nir acknowledges in her interview on the Times website that she speaks none of these languages herself and relied on translators for crucial parts of her story. She seems unaware of the irony in this: she claims to have been able to determine the true general condition of the “vast majority” of salon workers, of whom there are tens of thousands, while 115 state inspectors, at least twenty-eight of whom know the languages that she doesn’t speak and which are predominant in the industry, lack the “essential” linguistic tools.

But the most serious flaw in the Times story, aside from its misrepresentation of the classified ads, is its strenuous effort to portray Ms. Ren—whose story takes up a major share of the article and who is the only salon worker whose life is described in detail—as a representative figure of the salon industry. Certainly, much of the account Ms. Ren gives the Times is appalling and the treatment she received is reprehensible. As with undocumented and/or untrained workers in any industry, Ms. Ren, newly arrived from China, is particularly at risk of abuse, and exposing the mistreatment of her and others like her is a valuable service. But lacking both work experience and the required license, she cannot perform manicures legally in any salon. Many nail salons, including ours, as a matter of policy and to avoid fines, do not hire unlicensed workers. So how representative is her story?

In one of its few efforts to give empirical support to its claim that exploitation can be found in “almost any salon,” the Times says that it interviewed “more than one hundred” workers, only 25 percent of whom said they were paid at least the minimum wage. Very few of these workers are actually quoted from in the article, but in the Times summary, most of them turn out to be like Ms. Ren. “Almost all of the workers interviewed by The Times, like Ms. Ren, had limited English,” the exposé says. “Many are in the country illegally. The combination leaves them vulnerable.” In other words, the Times drew its conclusions about the “vast majority” of workers at “almost any” salon in New York by interviewing a pool of mostly undocumented, untrained, or unlicensed workers like Ms. Ren, ignoring clear evidence that tens of thousands of salon workers do not fall into this category.

The question of licenses is critical. It is not clear from the Times story how many unlicensed workers there are and how many salons are willing to hire them. According to the Department of State of New York, as of May 2015, there were 30,610 licensed manicurists in New York; in 2014 alone, 1,182 new “nail specialty licenses” were issued. These facts are unmentioned in the article. To get a license, a candidate has to go to an accredited school for about three months of classes, costing just under $1,000, and then pass both written and practical exams; the instruction and the exams are offered in Korean, Chinese, and Spanish. No mention of this standard accreditation process is made in the Times story. In fact, Ms. Nir offers not a single quote from one of these 1,182 newly licensed workers, or, indeed, from any salon worker who is identified as having a license and a few years of experience, even though such people can easily be found in salons all over the city.

Paradoxically, the Times’s own website has now provided a very different view of the salon industry, in an interview with a Chinese woman, a veteran salon worker in the New York area, that was recently published on its China blog, Sinosphere. Much of the interview contradicts Ms. Nir’s article:

Q. What are your thoughts on the New York manicure industry in general?

A. I think it’s fine. Many of my friends have been doing the work for more than 10 years, and they generally think it’s better than working in restaurants. The difference between a manicurist and her boss is not clear-cut. An ordinary worker can start in a nail salon to learn the techniques, and, after three or five years, she can pay around $30,000 to buy a salon and become a boss herself. I found this highly inspiring. Even when I was cursed or when my customers found fault with me, my heart was still full of hope, because one day I could become a boss, too.

In fact, by the end of the very long Times exposé, something like the upward mobility described here seems to be happening even to Jing Ren. At one point in its portrayal of her, the Times quotes Ms. Ren as “petrified” that her conditions of abysmal pay will last forever. But in the final lines of the Times exposé, we learn that this embodiment of the exploited salon worker has, a few months after her first day at her first salon, gotten a new job at another salon paying $65 a day, which with tips and commissions means that she too is almost surely earning upwards of $100 a day.

In other words, Ms. Ren seems to have made a kind of calculated decision. She’s worked for very low wages in exchange for the experience and training she needed to get a better job, and now she has one, perhaps by answering one of the thousands of classified ads ignored by the Times account. Ms. Ren’s cousin and mother, who, we learn at the end of Ms. Nir’s account, also work as manicurists, are likely following the same route. They might also eventually get licenses allowing them to do massage or facial treatments, in which case their pay will go up. If they pool their money, as many immigrant families do, their combined earnings could be several hundred dollars a day or more. This is certainly not affluence by New York standards, but neither is it the “rampant exploitation” that the Times claims to be pervasive and inescapable.

How to account for these evident flaws, the one-sidedness of the Times story? Recently the Times’s own Nick Kristof wrote in a column that “one of our worst traits in journalism is that when we have a narrative in our minds, we often plug in anecdotes that confirm it,” and, he might have added, consciously or not, ignore anecdotes and other information that doesn’t. The narrative chosen by the Times, what might be called the narrative of wholesale injustice, is one of the most powerful and tempting in journalism. Certainly, as Mr. Baquet put it, it had “impact.” It was read, he told an audience in mid-June, by 5 million people, which is five times the readership of the Sunday print edition, and produced an immediate government response.

But the quest for impact can overwhelm a newspaper’s primary responsibility for accuracy. If the Times had revealed that undocumented workers in the salon business are being subject to abusive treatment, it would have served a useful and important purpose. But in extrapolating from the experience of Ms. Ren to make assertions about that “vast majority,” the paper has put its tremendous prestige and power behind a demonstrably misleading depiction of the nail salon business as a whole.