For the painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet, genuine art was chaotic, unlearned, and driven by “instinct, passion, mood, violence, madness.” It was created by those who had no schooling in the arts. “There was more art and poetry in the talk of a young barber,” he wrote in 1945, “than among the specialists in art and poetry.” He believed the best examples were found in the work of the mentally ill, who, he argued, were unafraid of the “ecstasies of the mind,” which served as a private reserve for their work. Dubuffet spent decades collecting examples of this “savage art to which no one pays any attention,” which he called “art brut.” This work, nearly two hundred examples of which are now on view at the American Folk Art Museum, embodied for him a spontaneous and immediate way of making art, an untrained rawness. Art brut was a source of inspiration for his own work, which ranged from primitive-looking drawings scratched into impasto to a totemic figure composed only of two unmodified grapevine roots and a block of slag. But he also advocated tirelessly to spread art brut’s influence as a movement, from postwar France to New York and, in particular, to Chicago. Dubuffet’s greatest contribution to contemporary art, beyond his own work, may have been his validation of an art of instinct and his insistence on what he called an “infinitely diversified expansion” of art history.

Unlike his art brut practitioners, Dubuffet was well versed in cultural history. Born in Le Havre in 1901 into a family of wine merchants, he attended art school and studied the humanities. But academic influence, he felt, took him further from an intimacy with the common man. A stint in the family business and a marriage he described as being perfectly bourgeois did little to help. He read parts of the Austrian physician Hans Prinzhorn’s Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922), a book that had influenced Paul Klee and many other early-twentieth-century avant garde artists whose work was shown in the Nazis’ infamous degenerate art exhibition. The book had a pronounced effect on Dubuffet, as did, later on, the carved wooden sculptures of the French psychiatric patient Auguste Forestier, which spurred Dubuffet to seek out similar works that would eventually form the basis of his art brut collection.

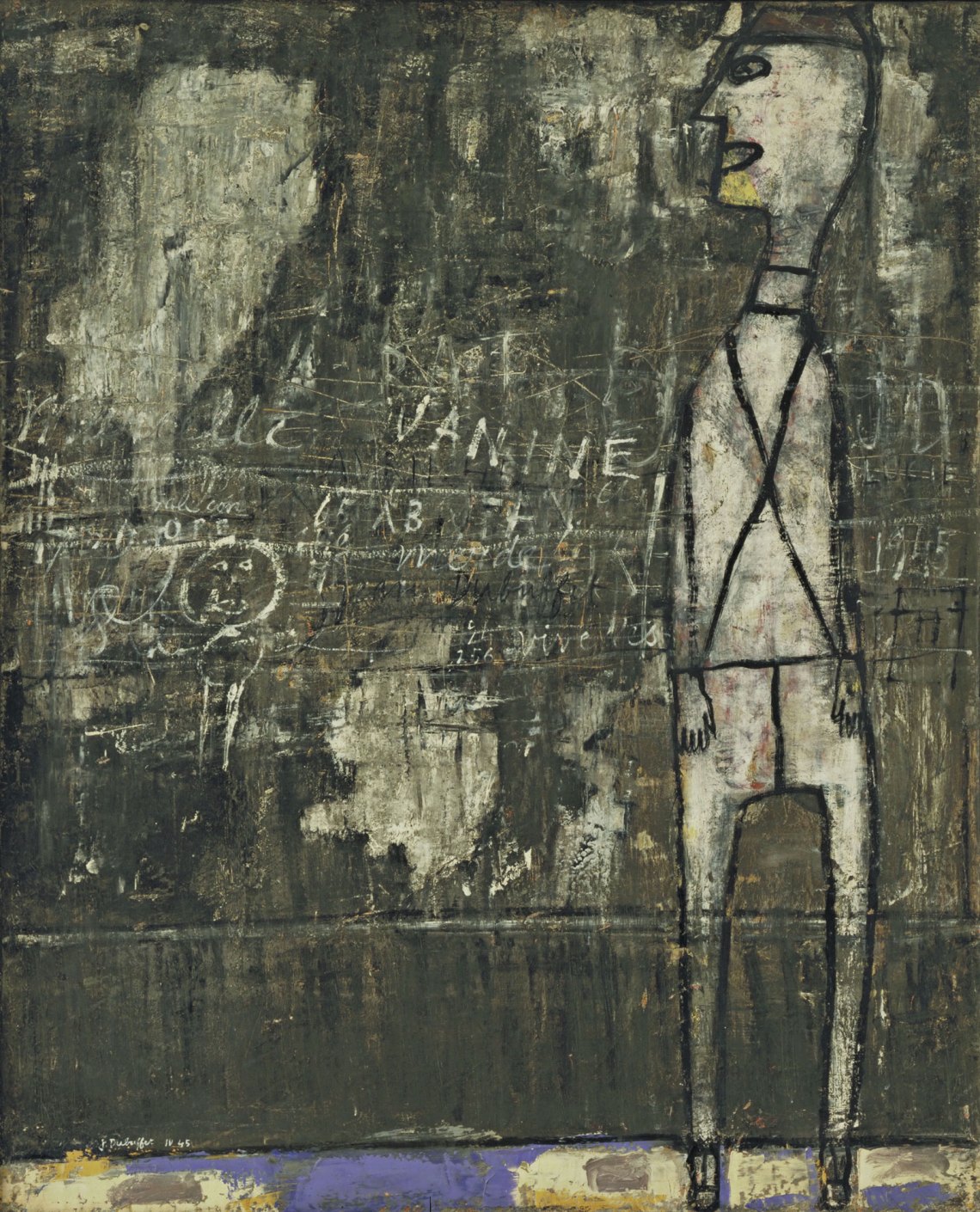

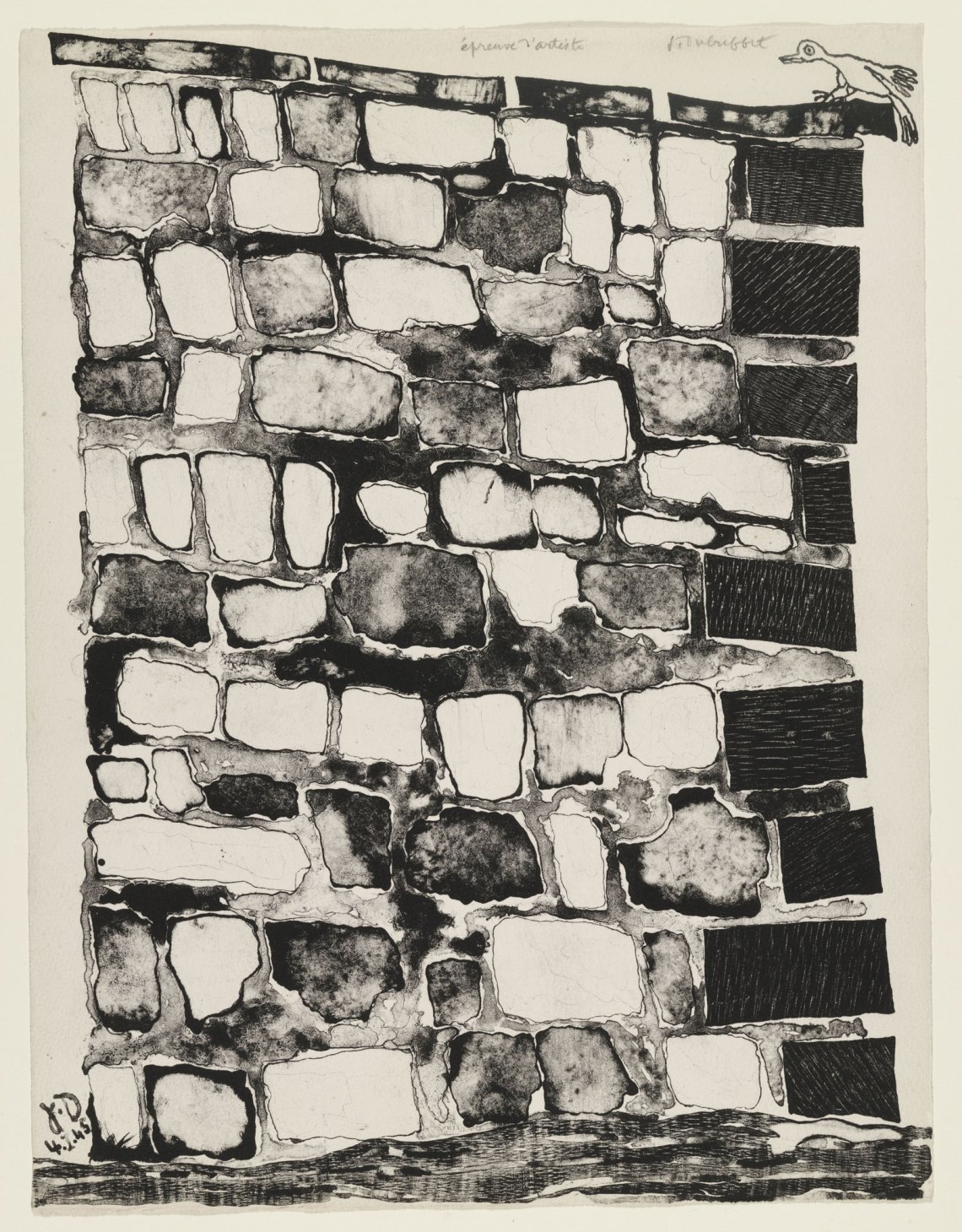

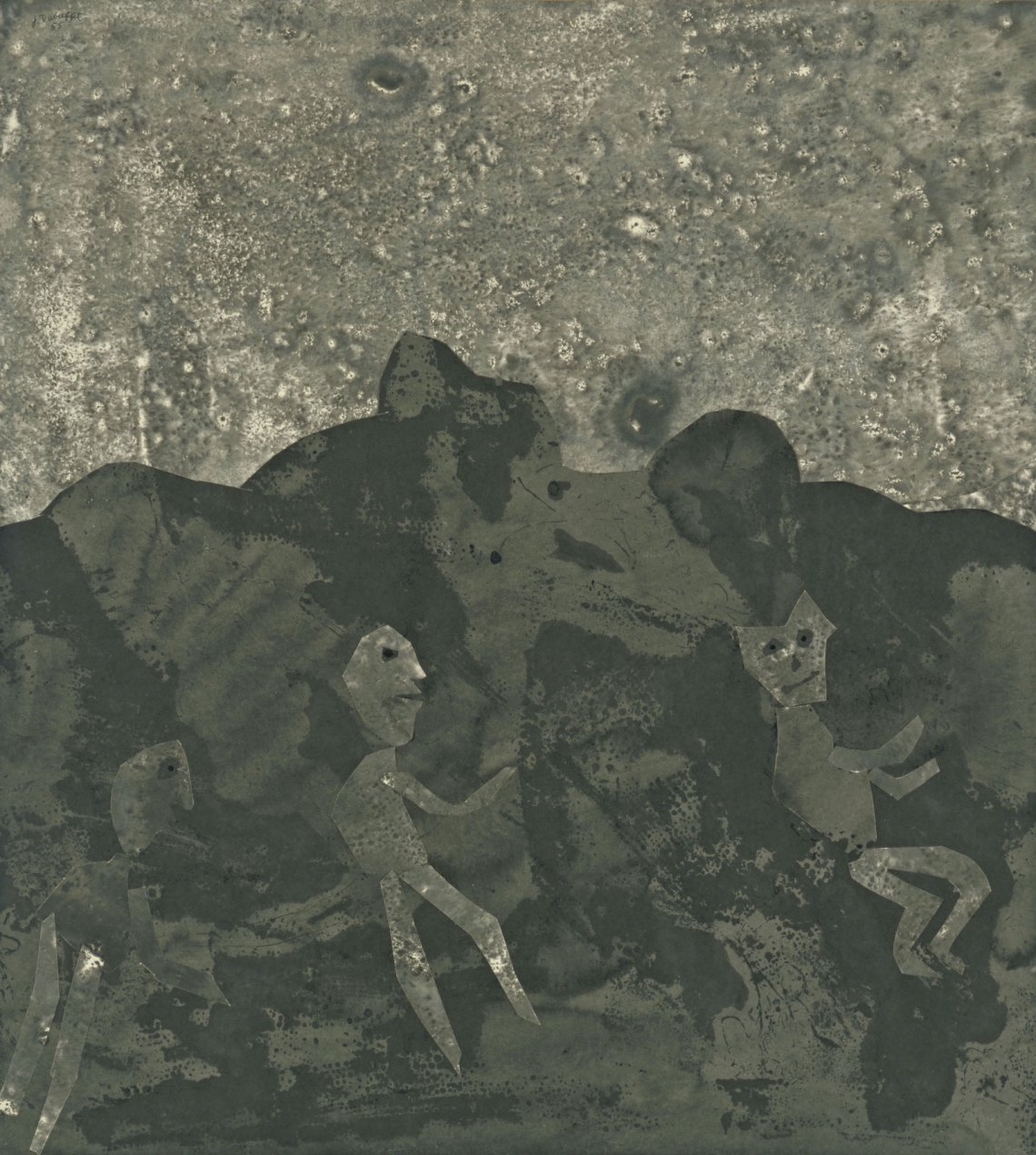

In his quest for rawness and novelty in his own art, Dubuffet passed through many different styles or periods, a progression that the Museum of Modern Art’s recent survey, “Jean Dubuffet: Soul of the Underground,” attempted to outline by drawing on nearly ninety works from its collection. In the 1940s, for instance, Dubuffet liberated himself from the unwanted influences of the academy in part by studying what he called the “thrilling folie-bergère” attitude of the Paris streets and the new metro, both of which offered a direct connection to the vigor and informality of daily life. His paintings and lithographs from the postwar years are a carnival of archaic-looking nude figures and crumbling, graffitied walls.

Dubuffet’s work also drew on cultures that, as he saw it, had developed apart from a Western fine-art tradition. Between 1947 and 1949, he made three trips to Algeria. There he found an appealing strangeness in the indecipherability of the language (despite having studied an Arabic dialect for three years) and in the shifting desert landscape, celebrating what he perceived (with a whiff of ethnocentrism) as being improvisatory and ephemeral. A drawing from 1948, taken from Dubuffet’s Algerian sketchbook, shows the outlines of some two dozen footprints overlapping one another and turned every which way—one footprint disappearing under the lines of another, both dissolving into meaningless, transient marks.

In 1947, Dubuffet introduced stones and sand into his paintings; later, soil, leaves, slag, citrus peels, and wood. For La Piste au désert, a painting from 1949, he used oil, putty, sand, and pebbles to create a pocked, earthy surface that replicates the look of a weathered artifact. Some thought his materials were silly. A headline in Life magazine in 1948 trumpeted, “Dead End Art: A Frenchman’s Mud-and-Rubble Paintings Reduce Modernism to a Joke.” But the notoriously belligerent critic Clement Greenberg, writing in 1949, declared Dubuffet to be “perhaps the one new painter of real importance to have appeared on the scene in Paris in the last decade.”

Dubuffet’s work, as art historian Aruna D’Souza has written, is conspicuous as a model for a new kind of art. It affirmed, in part, Abstract-Expressionism’s “vulgar” impulses: in 1947, Dubuffet was showing abstract figures incised into impastoed paint with the wrong end of a paint brush or with his fingers; at the same moment, Pollock was beginning to pour skeins of house paint across canvases that also included nails, tacks, coins, and cigarettes. (In comparing the two, Greenberg faulted Dubuffet for clinging to figuration while Pollock was able to eliminate explicit subject matter from his work.)

While making his own art, Dubuffet advocated on behalf of art brut in famously eloquent pamphlets, speeches, and manifestos. In 1951, he gave a talk at the Art Institute of Chicago called “Anticultural Positions,” which set out his antiformalist, expressive style and his dissatisfaction with Western conceptions of beauty. He rejected the notion that certain objects are more beautiful than others, advocating instead for the idea that “there is no ugly object nor ugly person in this world and that beauty does not exist anywhere, but that any object is able to become fascinating and illuminating.”

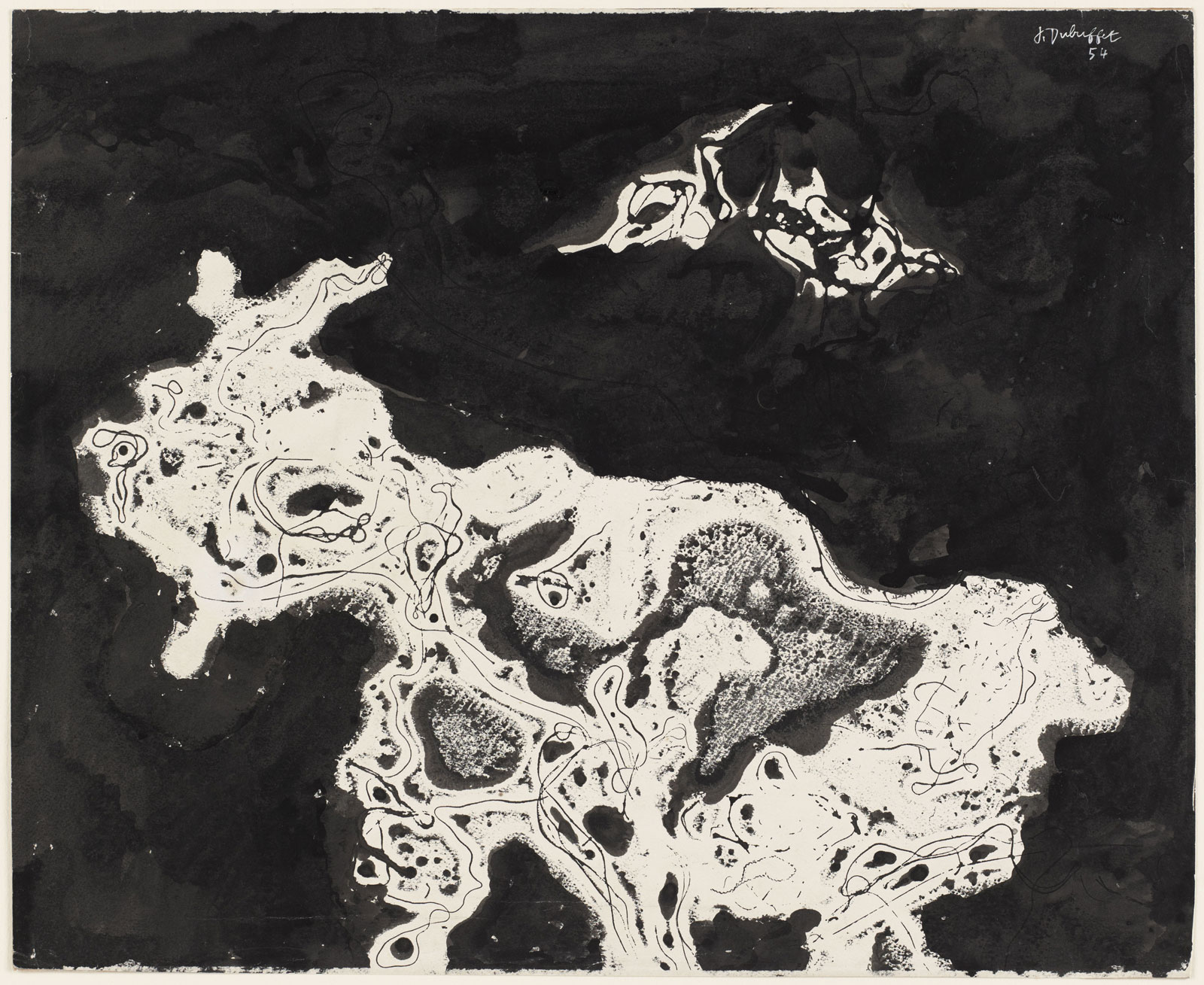

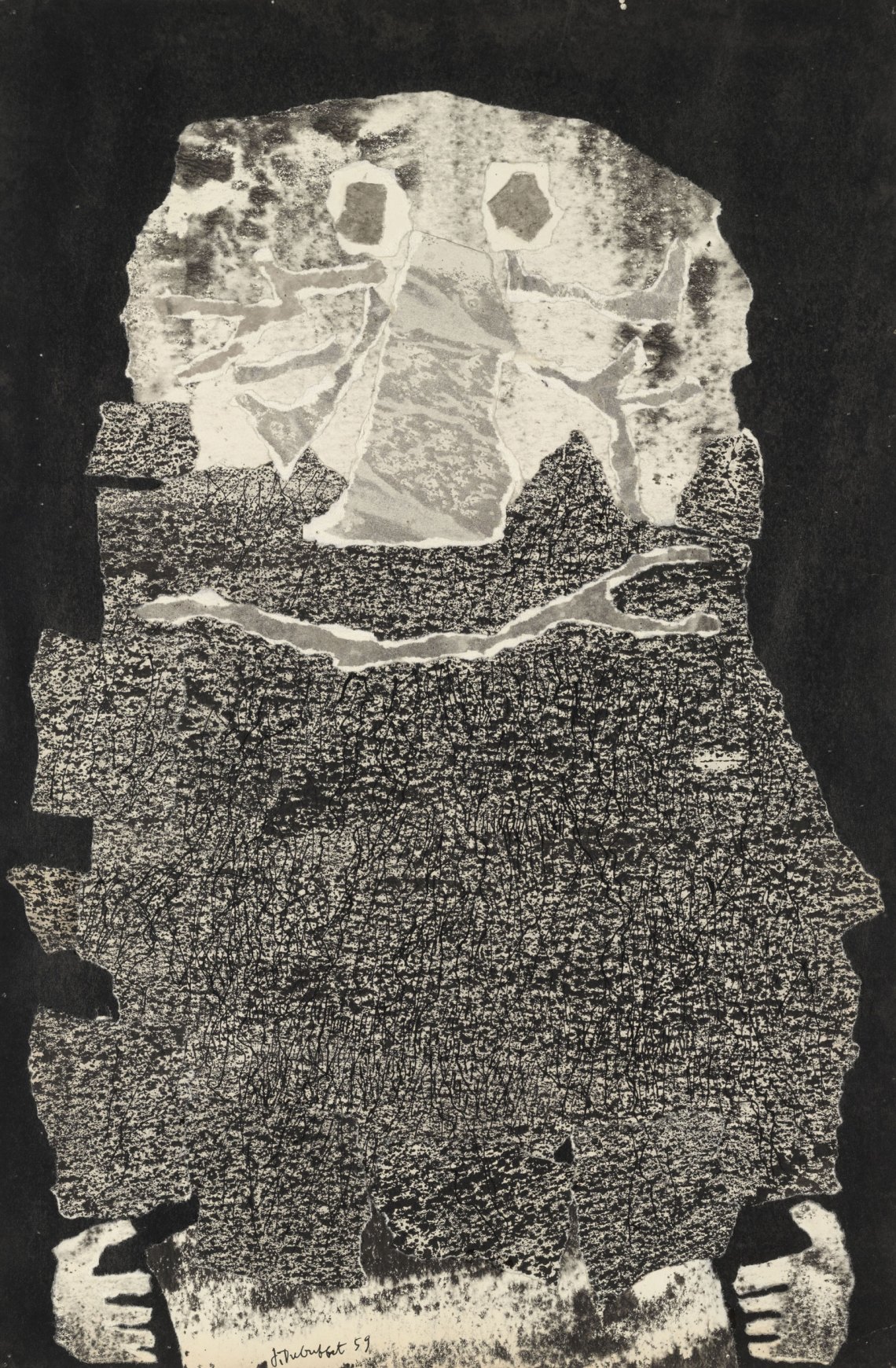

At roughly the same time as his Chicago speech, Dubuffet created a series of works that depicted perspectivally flattened tables whose amoeba-like surfaces are crammed with objects. “I am convinced that any table can be for each of us a landscape as inexhaustible as the whole Andes range,” he wrote. Evolving Portrait, a drawing from 1952, depicts a head and torso similarly suffused with a profusion of squiggly marks. His ink-on-paper landscapes from the same year are exploded versions of the same dense, chaotic marks.

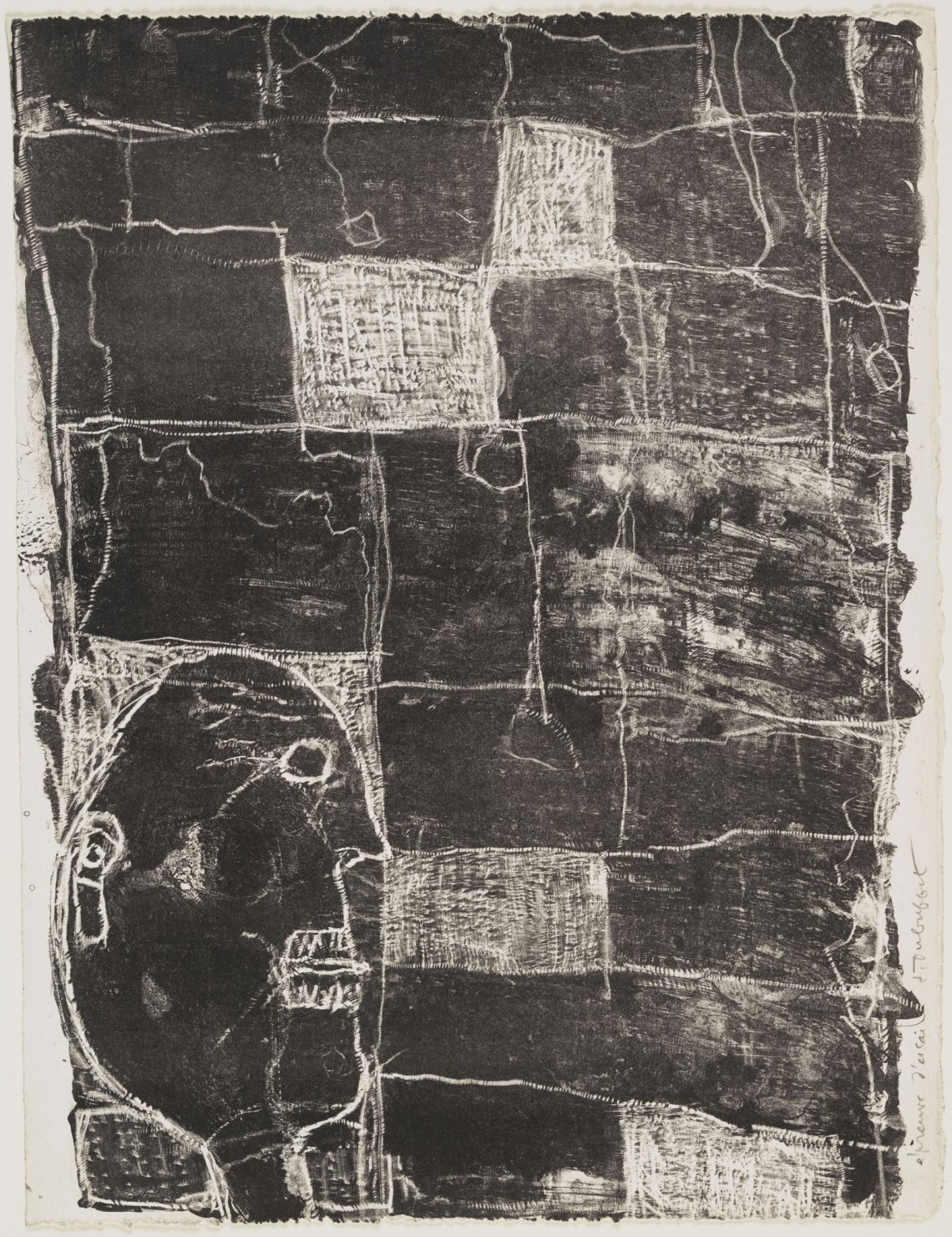

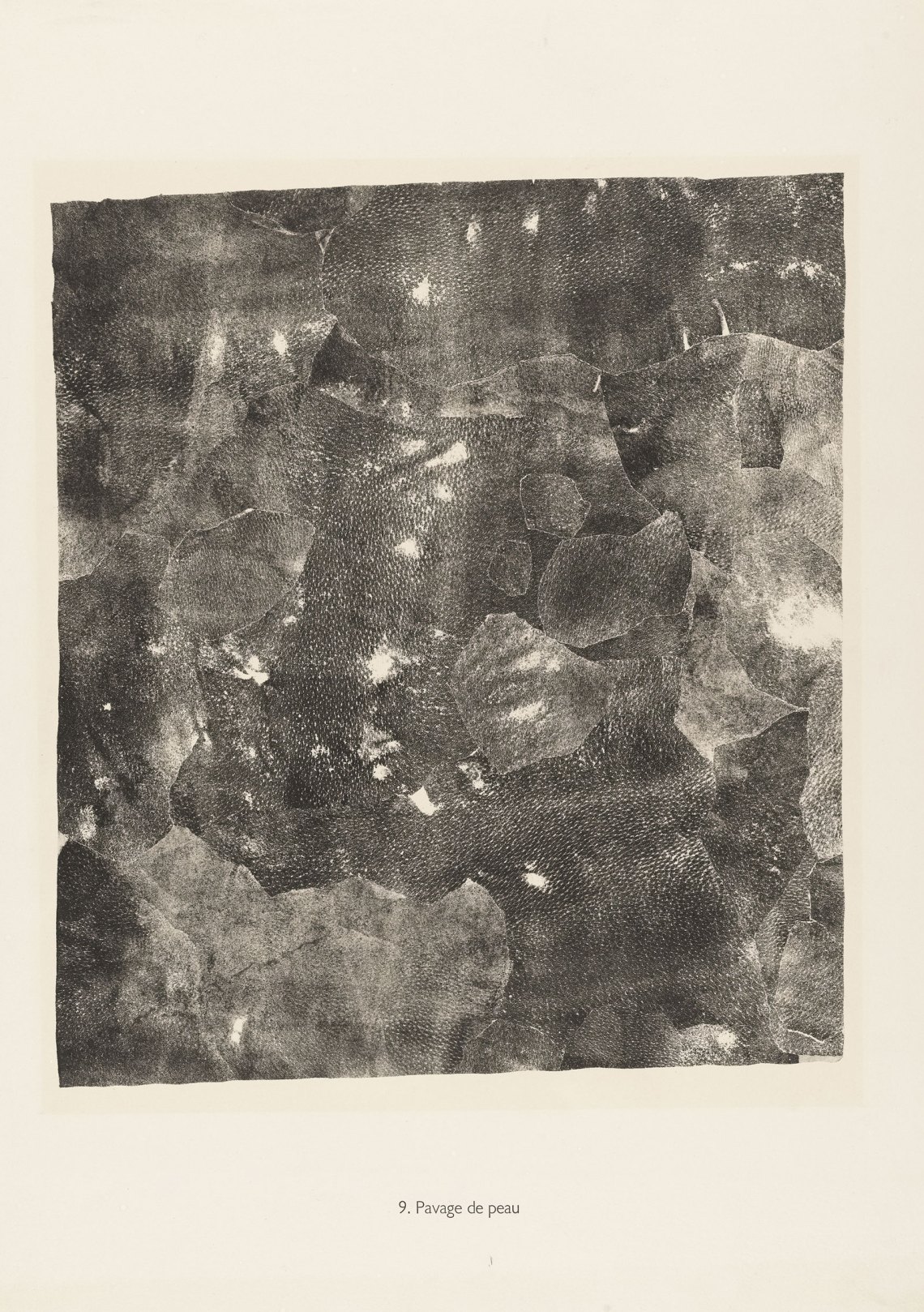

By 1960, a thick network of lines fills the canvas in a drawing titled Epidermis, but the marks have become so massed and compact that the view might be microscopic or seen from a great distance. Dubuffet’s primitive impulse became thoroughly notional in Phenomena, a series comprising some three hundred lithographs that mimic the look of natural textures and surfaces. He then cut up these lithographs for use in his collages; they existed as a reserve of imagery much like that utilized by art brut’s practitioners.

Dubuffet was steadfast in his creative vision, and his art is remarkable for the variety with which he explored every aspect of its expression. It reached perhaps its best-known phase with L’Hourloupe, an idiom he discovered in the early 1960s while doodling at the telephone, in which black lines framed cells of unmixed vinyl paint, often red and blue. In later years he went on to create large scale outdoor sculptures and figures made from polystyrene and epoxy.

The trajectory of twentieth-century art history has long been a fairly tidy one, with artists of similar sensibilities herded into neat groups; those who fall beyond these bounds are too often left out of the story, sometimes “rehabilitated” only decades later. But art brut offers a ready example of looking beyond expected lines of investigation into what Dubuffet praised as “new values not yet perceived.”

Art Brut in America: The Incursion of Jean Dubuffet is on view at the Folk Art Museum through January 10.