It was in the Great Depression years of the mid-1930s that American boys of impressionable age began a final romance with the Old West. There is little mystery in it. Real life was pinched, mothers fretted and fathers spoke sharply, everyone counted pennies. But in the Old West of romance a boy had his own horse, the stagecoach carried gold, a rancher’s fortune was made if he could get his cattle across the river, and the cavalry always came over the hill with a moment to spare. When they appeared the Indians ran or were shot in profusion from their horses.

At the heart of the romance were two great mysteries. One was girls, who saw something boys did not, or did not quite; the other was Indians, who had been exempted by the Great Spirit from the things that made white boys chafe—Saturday night baths, long hours in schoolrooms on sunny days, chopping stove wood, sitting in parlors when guests came. The heart of the Indians’ appeal was this: they did as they pleased. In the fall of 1933 the Chicago Tribune printed a new Sunday comic built around girls and Indians that was written and drawn by an all-around newspaperman from Wyoming named Garrett Price. The strip’s name, White Boy, promised a world of exotic excitements. The hero was just that, a slender, nameless lad who left everything familiar when he was captured by Indians, given to a woman whose own son had been killed by whites, and adopted into the tribe.

Garrett Price (1895-1979) is best known for his work over a half century for The New Yorker, hundreds of cartoons and a hundred covers, including two during the magazine’s first year (“Paris Café” and “Heat Wave,” August 1 and 29, 1925). The long-forgotten three-year run of White Boy (renamed Skull Valley at the halfway mark) has now been republished in its entirety, about a hundred and fifty strips, by Sunday Press Books of Palo Alto, California. It is a big (16 by 10 ½ inches), sumptuous volume in color providing a rich sample of the work of a gifted artist with a sly sense of humor and a sure feel for the line—so sure that the line is pretty much the whole of his style. Price was in his late thirties when he created White Boy to fill a request of the Tribune’s editor, J.M. Patterson, but there was enough of the boy left in him to focus on the mysteries of girls and Indians.

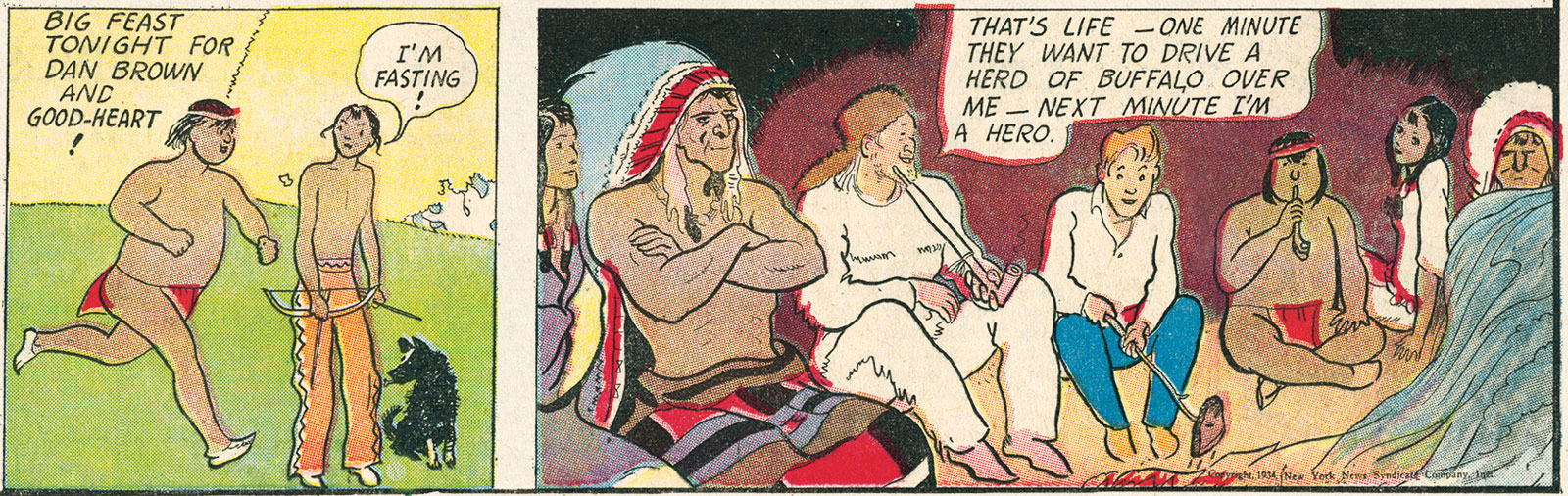

Read now, the strip is politically incorrect in a cheerful way, comfortably calling the principal girl “Little Squaw.” Her given name is Starlight, and she is frankly presented as a long-legged maid in a buckskin dress with kissable lips of the Clara Bow sort who soon has White Boy’s full attention. The Indians are a range of types from central casting: chiefs in feathers, two Indian boys, warriors with oddly chosen names like Trips-Over-a-Dog and his brother, Brother-of-Trips-Over-a-Dog, and a sinister elderly fellow with dark purposes called Snakeface, whose eye is on Starlight. Price’s strips reveal a week at a time what interested him as a writer and an artist. As a writer he is drawn to a kind of camp humor, poking fun at the conventions of the western tale, and as an artist he loves bold composition and grand drama.

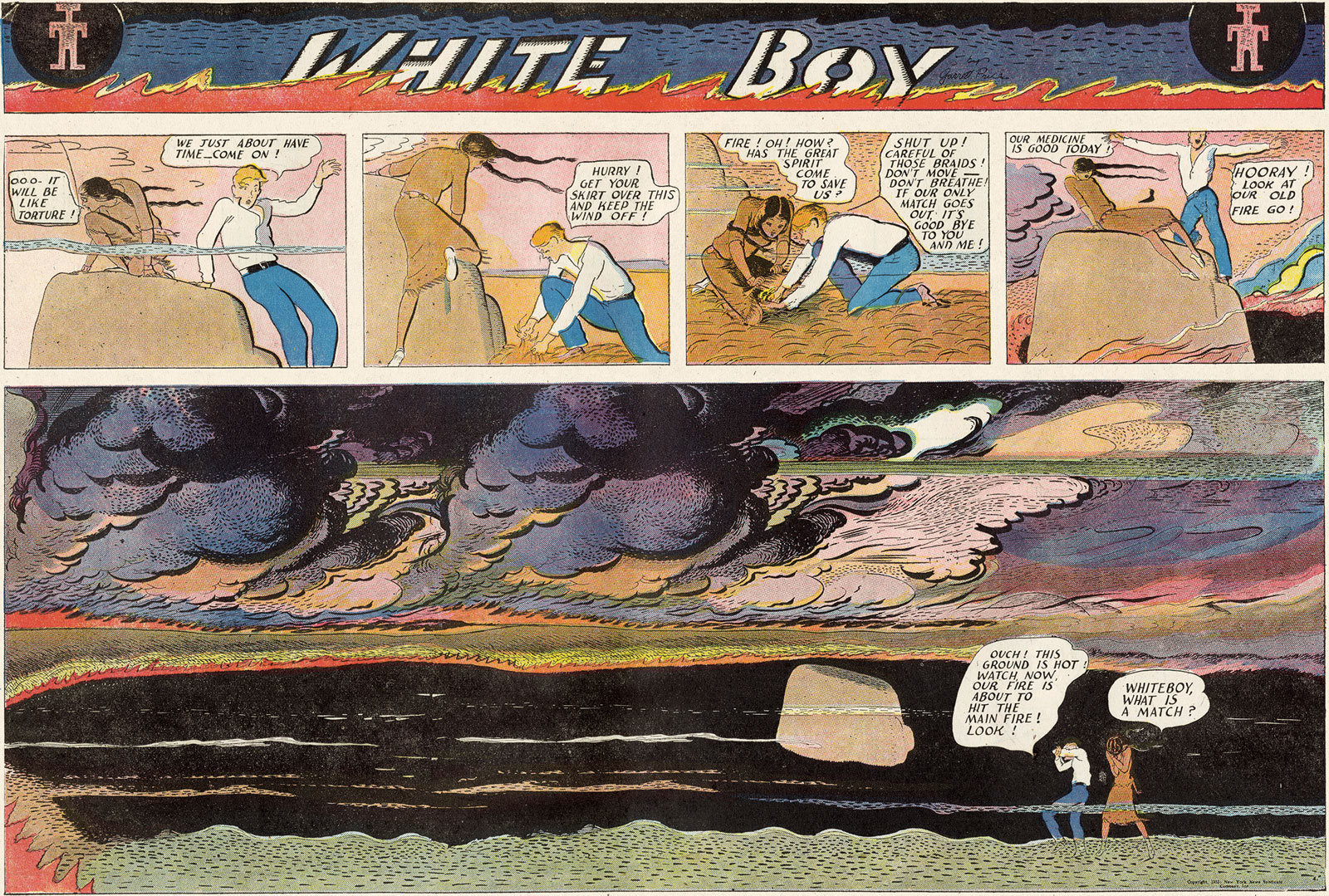

In an early strip of only three panels, instead of the usual seven or eight, Price fills his page with a panorama of White Boy and Starlight trapped by a prairie fire and threatened by stampeding buffalo. White Boy searches his pocket and finds a single match with which to start a counter-fire to save them from death. “What is a match?” asks Starlight. In the next strip they get the fire going and are portrayed at the center of one long panel in black, burned-over ground while flames and smoke around them fill a quarter page of the Sunday paper. “White Boy,” asks Starlight again, “what is a match?”

It is obvious that Garrett Price had a good time with White Boy, drawing heavily on his boyhood home in Saratoga, Wyoming, which was serious farming and ranch country but so remote and isolated (about sixty miles east of Laramie) that Price once rode eighty miles to see a circus. The early 1900s was a golden age of Old Timers—the men who had gone west before the Indians were confined to reservations, and the buffalo had been hunted close to extinction. Price’s character Trapper Dan Brown was a familiar frontier type, with a high opinion of himself and a low opinion of Indians.

Advertisement

In one strip Trapper Dan challenges Lark Song, a noted orator in his tribe, to best if he can a song Dan has written. One verse goes:

Oh, I don’t like books

and I don’t like tea,

I wrassled a bear

when I was three.

Ki-Yi-Yippy-Yippy Yea.

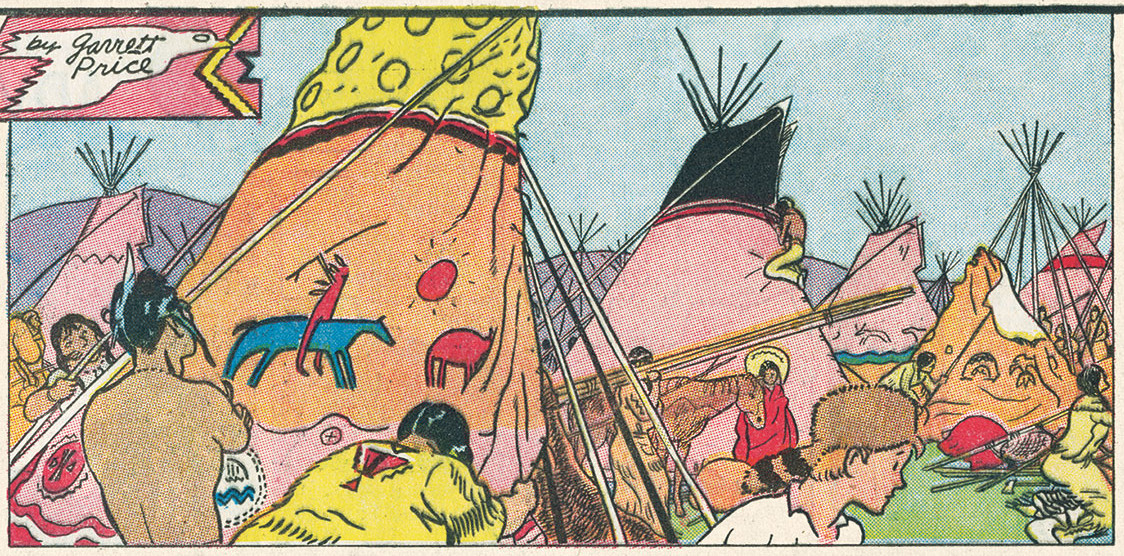

Dan tells White Boy he knows Redskins—“one White Man is worth a whole tribe of them.” But Garrett Price has none of the anti-Indian prejudice typical of Wyoming Old Timers when he was a boy. There is nothing threatening about his Indians, who run the usual range of human types. What interests Price most is drawing, capturing the looks and gestures of his characters and the life of the Plains, as he does in one strip (June 3, 1934) devoted to the Indians striking camp. It is full of the romance of times gone by.

But the truth is that Price’s interest in Indians was shallow and I would argue that his early, enamored drawings of Starlight worried his editors. After the early strips she stops hiking her skirt. Near the end of the second year the strip was altered more thoroughly and abruptly. Changing the name to White Boy in Skull Valley was the least of it. The hero is now Bob White, the girl is Doris—same girl, same lips, but wearing short hair, jodhpurs, and boots. The time is more or less modern-day (cars, a boat with an outboard), with assorted bad men, a dude ranch run by a beautiful redhead, a sinister landlord ready to foreclose when the mortgage money is late. The change went unexplained but the editor of the Sunday Press collection, Peter Maresca, guesses reasonably that Price’s boss at the Tribune simply tired of the Indians, and it is likely this also explains the sudden death of the strip in August 1936.

The glory of White Boy is largely found in its opening weeks and later, intermittently, with story lines involving wild beasts and dramatic scenery that interested Price when he had a pen in his hand. Two strips depict a fight between a mountain lion and a black bear in a tree over a raging river. The drawings don’t have much to do with “the story” but are full of tense drama.

Another run of strips are all about buffalo and an Indian who dreams he has become one of them. It’s the buffalo action that interests Price, not what happens to the Indian when he regains his old identity as Good Heart, “the lost son of our chief.” Continuity was the chief motor of the Sunday comic strip in the 1930s. Price was good at setting a story in motion, and he was among the first comic artists to borrow film techniques—the close-up, the unfolding panorama of action, the focus on significant detail. But he had no patience for the week-in, week-out pursuit of characters through the whole of an improbable story.

Garrett Price was a different artist during his later New Yorker years, when he lived in Westport, Connecticut. The subjects in his cartoons have pot bellies at the beach and noses like parrot beaks, are baffled by the world, and cannot remember what it was like to hike a skirt, or to watch it happen. Some of his covers have a stunning, wistful beauty, like a 1956 cover of circus queens riding elephants into the ring, a 1949 cover of a boy all alone on a spring ball field sliding into home plate, and a 1951 cover of autumn leaves falling over a summer house being closed for the winter—a husband sits waiting in the car as his wife gathers a last armful of flowers. Price’s wife died of lung cancer in 1973, his last cover ran the next summer, and Price himself died in 1979. One previous collection of his work, Drawing Room Only, mainly New Yorker cartoons, was published in 1946.

Garrett Price’s White Boy in Skull Valley is published by Sunday Press Books.